An American in Marseille

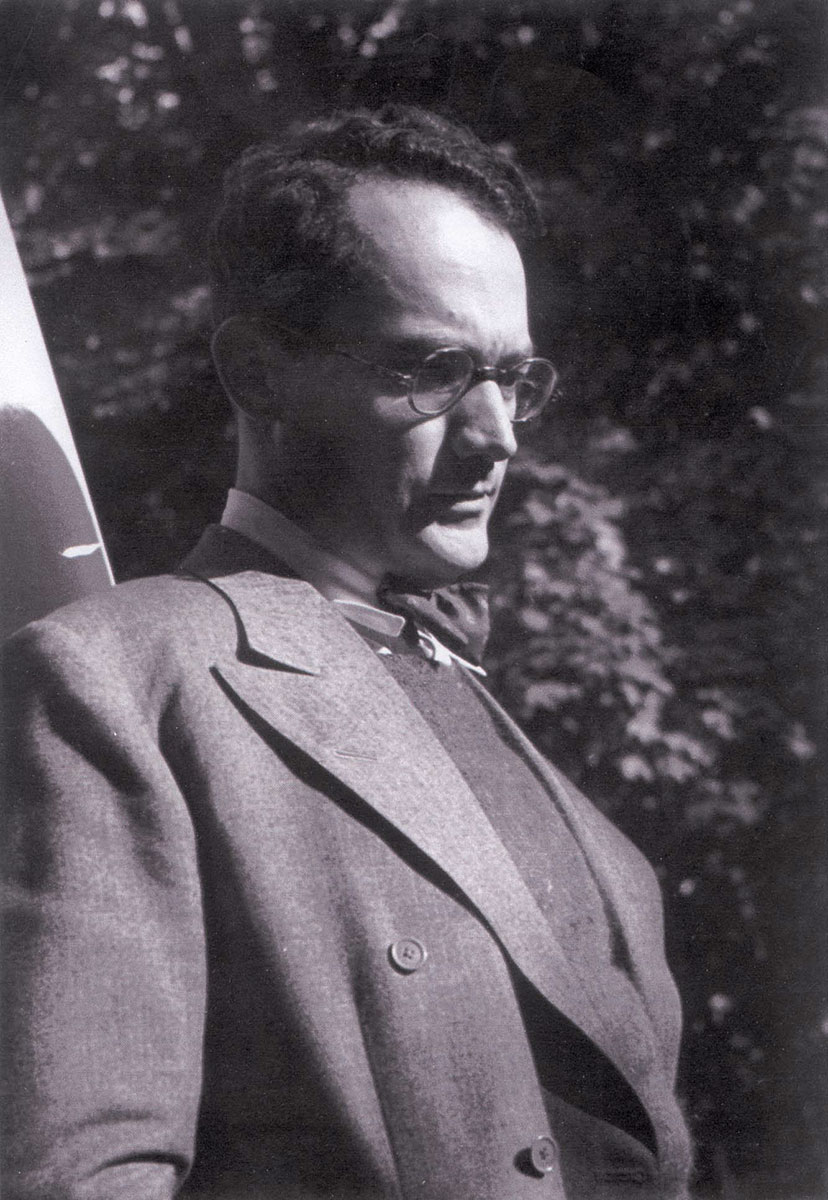

According to the armistice agreement signed after the fall of France in June 1940, France was obligated to turn over to the Germans all persons on the Gestapo’s wanted list - a large number of whom were Jewish intellectuals. The refugees from Germany who had sought shelter in France were once again under German control, and the danger to their person was grave. An aid organization - the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) – was established in New York with the purpose of helping intellectuals and renowned figures stranded in France, who were in danger of being arrested and turned over to the Germans because of their anti-Nazi stand. With the intervention of the United States President's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, the U.S. State Department, agreed to make an exception to its otherwise restrictive visa policy, and to provide entry visas to a limited number of two hundred refugees. Varian Fry, a classisit by education who worked in New York as an editor for the Foreign Policy Association, was sent by the Emergency Rescue Committee to France. His job was to reach Marseilles, where many of these refugees were staying, and to find a way to get them out. He had a list of two hundred names of those eligible for visas, and a sum of $3,000 on his person.

Arriving in Marseilles in August 1940, Fry settled in his room in the hotel Splendide, and began writing letters to the people on his list. Rumors of his arrival had spread, and hundreds of people came to ask him for assistance. He soon discovered that the American consulate was not going to help him get people to the US, and that he would have to work independently. Faced with the plight of the desperate refugees, Fry decided to act and began finding ways - most of which were illegal - to smuggle out those refugees who faced immediate danger of falling into German hands. The lines of refugees in front of his hotel room were so long that he rented an office and put together a group of associates – American expatriates, French nationals and refugees – to help him in the process of classification. They established the American Rescue Center (Centre Americain de Secours) and began interviewing between 60-70 people every day. Years later Fry described how he faced the dilemma of who was to be helped: "We had no way of knowing who was really in danger and who wasn’t. We had to guess, and the only safe way to guess was to give each refugee the full benefit of the doubt. Otherwise we might refuse help to someone who was really in danger and learn later that he had been dragged away to Dachau or Buchenwald because we had turned him away."

Although he had no experience in underground work, Fry put a manifold operation into place. His office dealt in legal as well as illegal ways: Once the two hundred US visas were exhausted, Fry's office tried to obtain visas to other countries; a former Viennese cartoonist was enlisted to forge documents; some refugees were smuggled on French troopships to North Africa – still under French control – disguised as demobilized soldiers; other refugees were spirited out of France over land.

Fry tried twice to appeal to US Secretary of State Cordell Hull. "Thousands find themselves in prisons and concentrations camps of Europe without hope of release because they have no government to represent them….Cannot the US and other nations of the Western Hemisphere take immediate steps, such as creation of new Nansen passports [formerly used to help stateless Russian refugees] and extension of at least limited diplomatic protection to holders of them?", he wrote on November 10, 1940. Both his letters remained unanswered.

Fry’s activities reached such significant dimensions that it became difficult to keep them secret. The French police decided to take firm action against him. The US Embassy in Vichy and the Consulate in Marseille, adhering to their country's strict immigration policy, didn't intervene on Fry's behalf. As a first step the French police raided his offices. In December 1940, he was arrested and held for a while on a prison ship in the Marseille harbor. But nothing deterred him from working on. He remained in France even though his passport expired, and continued his rescue activities. He was ultimately arrested by the French police in August 1941, given one hour to pack his things, and was then accompanied to the Spanish border. He was told that his expulsion had been ordered by the French Ministry of Interior in agreement with the American Embassy. Fry was to describe his departure: “It was grey and rainy as I boarded the train. I looked out of the windows and innumerable images crowded my mind. I thought of the faces of the thousand refugees I had sent out of France, and the faces of a thousand more I had had to leave behind”.

According to Fry’s estimate his office dealt with some 15,000 cases by May 1941. Of these, assistance was provided to approximately 4,000 people; 1,000 out of them were smuggled from France in various ways. Among the Jews Fry helped to smuggle out of France were a number of well-known figures, such as Hanna Arendt, Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, Siegfried Kracauer, Franz Werfel, Lion Feuchtwanger and many others.

When asked as to his motives, Fry responded that when he had visited Berlin in 1935, he saw SA men assaulting a Jew, and he felt he could no longer remain indifferent.

After his forced return to the United States Varian Fry was put under the surveillance of the FBI. For the rest of his life he was avoided by his former colleagues and friends and until his premature death in 1967 at age 59, he made a living as a Latin teacher in a boys' school. Shortly before his death, the French government awarded him with the Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur.

On July 21, 1994, Yad Vashem recognized Varian Fry as Righteous Among the Nations.

Varian Fry’s son planted a tree in his honor at Yad Vashem in 1996. The ceremony was attended by US State Secretary Warren Christopher, who on that occasion apologized for the State Department's abusive treatment during the war years.