The Witness to Murder Who Decided to Act

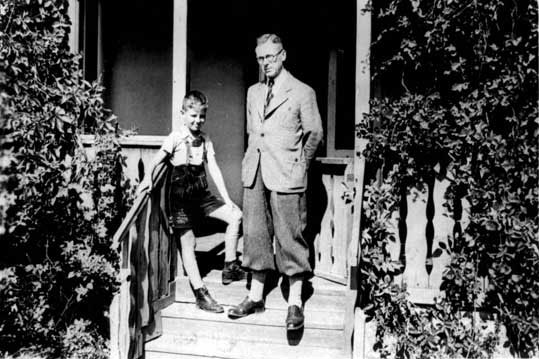

Hermann Friedrich Graebe was born in 1900, in Gräfrath, a small town in the Rhineland in Germany. He came from a poor family – his father was a weaver and his mother helped supplement the family’s income by working as a domestic. Besides the economic hardship, the Graebes were Protestants who lived in a predominantly Roman Catholic area. In 1924 Hermann Friedrich Graebe got married, and soon completed his training as an engineer.

Graebe joined the Nazi party in 1931, but soon became disenchanted with the movement. By 1934 – one year after Hitler's rise to power – in a party meeting he openly criticized the Nazi campaign against Jewish businesses. If he needed to be taught a lesson about the danger of such a move, it soon came. Following that incident, Graebe was apprehended by the Gestapo and jailed in Essen for several months. Fortunately for him he was released without trial.

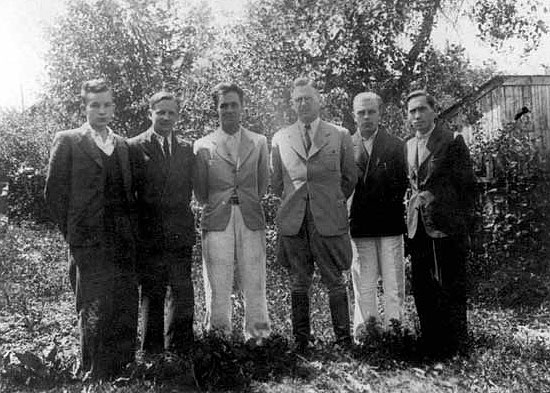

Graebe worked for the Josef Jung construction company in Solingen. From 1938 to 1941 his company sent him to supervise the construction of the fortifications on Germany’s western border, and in the summer of 1941, shortly after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, he was directed by the Todt Organization headquarters in Berlin to report to the offices of the Reich Railway Administration in Lwow (today Lviv in Ukraine). His assignment was to recruit construction teams to help build and renovate structures that were essential for the maintenance of railroad communications in the Ukraine. Arriving in Volhynia, a region in North West Ukraine, in September 1941, Graebe first set up his head office in Zdolbunov and proceeded from there to deploy his subsidiary offices throughout Volhynia and the former Soviet Ukraine. Graebe’s company, Jung, were employing a Jewish work force comprising some 5,000 men and women.

Graebe became witness to the atrocities perpetrated by the Germans and their Ukrainian auxiliaries against the Jewish population. In one of these incidents, on October 5, 1942, he was present at the mass-killing site at the airfield near Dubno and saw how 5,000 Jewish men, women, and children, lined up naked in front of previously dug pits, were cold-bloodedly executed by SS firing squads and the Ukrainians. After the war, his poignant accounts of the horrendous scenes he had witnessed in Dubno and elsewhere in the Ukraine were incorporated into the evidence of the Nuremberg trials, at which he testified for the prosecution.

Graebe was not content to remain a detached observer of unspeakable crimes. Propelled by his boundless moral indignation, he set out to save as many Jews as he could. By arguing that he was performing work essential for the German war effort, he deliberately accepted more assignments and contracts than his company could possibly handle. In consequence the need arose to employ a greater number of Jewish workers. Graebe went to great lengths to protect his Jewish employees and their families. In the process, he did not hesitate to compromise his position or property and—with time—even risk his own life.

In July 1942, Graebe learned from his Wehrmacht [German Army] sources of an imminent liquidation action to be directed against the Jews of Rovno. He had 112 Jews from the Ostrog, Mizoch, and Zdolbunov ghettos working for him in Rovno, and immediately obtained a “writ of protection” from the deputy district commissioner, and rushed to Rovno where, gun in hand, he managed to secure the release of 150 Jews. It was a very close call: the Ukrainian policemen were already busy driving the ghetto inmates to the collection point from where they were to be taken to their death. Graebe marched the lucky ones on foot to Zdolbunov, out of harm’s way.

The Germans went on with the liquidation of Wolhynia’s Jews. When, some months later, the Germans incarcerated the Jews of Zdolbunov in a ghetto and started deporting them, Graebe provided 25 workers with falsified “Aryan” identification papers. He subsequently transported them in stages, in his own car, to the far-flung company branch in Poltava, hundreds of miles to the east a place that was safer for the Jews. The Poltava branch was pure fiction: Graebe had set it up and maintained it at his own expense for the sole purpose of providing shelter for his Jewish workers. With the subsequent advance of the Red Army, the group was able to escape to the Russian side. Among those who were saved in this manner were Tadeus Glass, together with wife and son; Albina Wolf and daughter Lucia; Barbara Faust; Kitty Grodetski; and others. The transfer to Poltava was most dangerous to all involved. Had Graebe’s car been stopped at one of the numerous German roadblocks on the way, both rescuer and rescued would have been doomed.

In the course of time, Graebe’s uneconomic policies and unconventional practices began to arouse the suspicion of his company chiefs back in Solingen. They wanted to recall him and put him on trial for embezzlement, but this was never implemented. After the collapse of the German positions in eastern Poland, Graebe moved with his Jewish office team first to Warsaw and, from there, to the Rhineland. In September 1944, he defected with about twenty of his charges to the American lines, where he was still able to render valuable strategic advice concerning the West Wall.

From February 1945 until the autumn of 1946, Graebe worked closely with the War Crimes Branch of the U.S. Army on the preparation of the Nuremberg trials. He was the only German to testify for the prosecution at the Nuremberg trials. In 1948, after receiving threats against his life, Graebe decided to emigrate to the United States. Soon after settling with his family in San Francisco, he resumed his efforts to bring to justice German war criminals residing in the German Federal Republic. His constant preoccupation with the Nazi past went against the grain of postwar German society and made him something of a persona non-grata in his native country.

On March 23, 1965, Yad Vashem recognized Hermann Friedrich Graebe as Righteous Among the Nations.