Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613/822

Visas to Japan

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. Accordingly, when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, the Soviet Union occupied the country’s eastern parts. Following the Germans attack on Poland and the beginning of the persecution of the Jews there, many fled eastwards. Some 15,000 Jews from Poland arrived in the still independent Lithuania. Caught between the Nazis and the Soviets, they were desperately seeking ways to emigrate. When the Soviets occupied Lithuania in 1940, the Jews’ plight intensified.

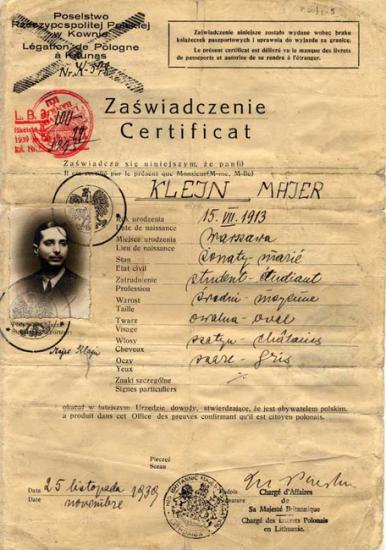

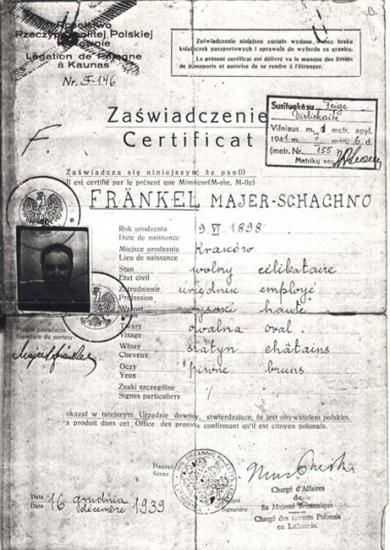

In November 1939, Chiune-Sempo Sugihara, a Japanese career diplomat, was sent to Kovno (Kaunas), then the capital of Lithuania, to serve as Japan's Consul. As part of his job, he was to monitor the maneuvers of the German Army across the border, so that Japanese headquarters would know in advance of the anticipated German attack on the Soviet Union.

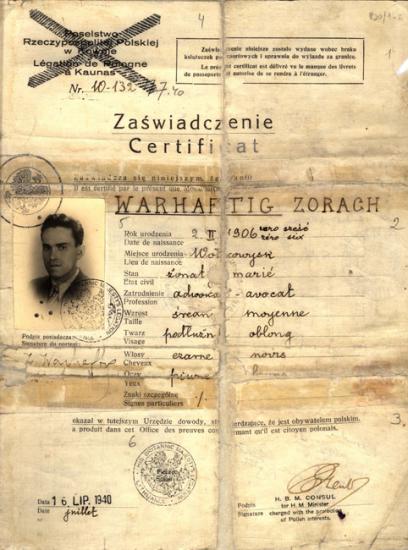

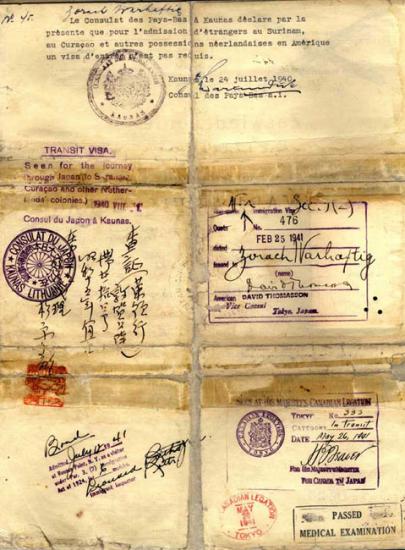

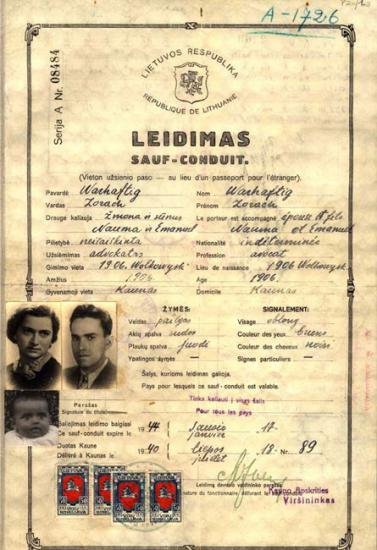

When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940, all foreign diplomats were asked to leave Kovno by the end of August. As he was packing his belongings, Sugihara was informed that a Jewish delegation was waiting in front of his consulate, asking to see him. The delegation was headed by Zerach Warhaftig – a Jewish refugee who was to become years later a minister in the government of the State of Israel. Sugihara agreed to meet with the delegation for a brief conversation. The Jewish delegation had come with a desperate request.

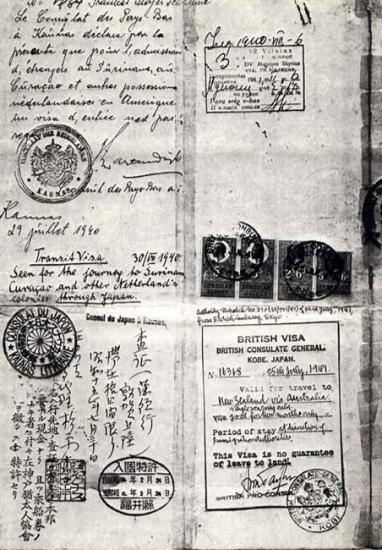

The Jewish refugees in Lithuania were in dire straits, watching as the gates to the world were closed to them. It had become practically impossible to obtain immigration visas to anywhere in the world. In their desperate search for countries that would permit them to enter, they had found out that Curacao – a Dutch colony – required no entry visas. This would enable them to leave Lithuania, but since the war had blocked all travel possibilities westwards, the delegation had come to the Japanese Consul with the request to issue transit visas. With these transit visas they would be able to obtain permission to cross the Soviet Union.

The Japanese consul asked for time to obtain authorization from his superiors to grant the visas. Nothing indicated that the Japanese Foreign Ministry would agree to this unusual request. However, Sugihara was very troubled by the refugees' plight and therefore began issuing visas at his own initiative and without having obtained his ministry’s support. Nine days later, the response from Tokyo arrived. The ministry rejected any change in the instructions and reiterated that the conditions for issuing transit visas were the existence of a valid visa for the applicant's final destination and proof that the applicant would be able to pay the travel to their final destination and for their stay in Japan. Although many of the Jews did not fall within these criteria, Sugihara decided to continue with the distribution of the visas anyhow. His wife later described how the predicament of the desperate Jewish refugees had affected her husband. After the meeting with the delegation, he was troubled and contemplative until he decided to go ahead and disobey his orders. Within a brief span of time before the consulate was closed down and Sugihara had to leave Kaunas, he provided between 2,100 and 3,500 transit visas. Thanks to Sugihara they were able to leave Europe and the murder that was to begin a year later. Among the recipients of visas were many rabbis and Talmudic students. Their narrow escape enabled them to re-establish the Jewish traditional schools elsewhere.

With a near deadline for leaving the country and a small staff, Sugihara stamped some of the passports himself. It is said that he was stamping passports even at the railway station, as he was leaving Lithuania. He also enlisted the help of some of the Jews to stamp the passports. With no knowledge of Japanese, some of the stamps were put in upside down. While all this was going on, Sugihara was receiving dispatches from Tokyo warning him against issuing visas without due process.

Over fifty years later, Sugihara's wife, Yukiko, described those days in an Interview to the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation: "At the beginning there were about 200 maybe 300 people. They stood there from morning till night, waiting for an answer. They also stood like this the following day and the day after. They stood all the time. And their small children together with them. People who had escaped from Poland, a place dangerous for them, and together with their children walking day and night, reached Kaunas and the Japanese Consulate asking for visas. They had risked their lives in order to reach this place, their bodies exhausted, their clothes torn and their faces tired. I would see them from my window, when they saw me looking at them, they would put their hands together (as if praying). It was so hard for me to watch these scenes… they were so miserable. Two days passed, and my husband sent another telegram, for the third time. The answer was the same answer, no matter how many telegrams: do not issue visas. We did not know what to do….We could not sleep at night. We kept thinking and thinking what to do. In addition to that, I had a baby, we had three young children. If my husband issues the visas contrary to the Foreign Office instructions, then when we return to Japan, my husband would for sure lose his job … We were thinking and thinking what to do, and the representatives of the refugees begged and begged ”please give us the visas".

From Kaunas Sugihara was sent to open a consulate in Koenigsberg (today Kaliningrad) and then to Bucharest. Upon his return to his country in 1946 Sugihara was dismissed from the Japanese Foreign Service. His understanding was that this was a consequence of his insubordination as consul in Kaunas. From then on he had to make a living doing odd jobs.

The visas granted by Sugihara saved the Jews from the Holocaust. When Nazi Germany invaded Lithuania in June 1941, the small window of escape was slammed shut. The killing of the Jews began immediately after occupation, and the majority of the Jews in the occupied territories were murdered.

On October 4, 1984, Yad Vashem recognized Chiune-Sempo Sugihara as Righteous Among the Nations.

Supported By: Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany