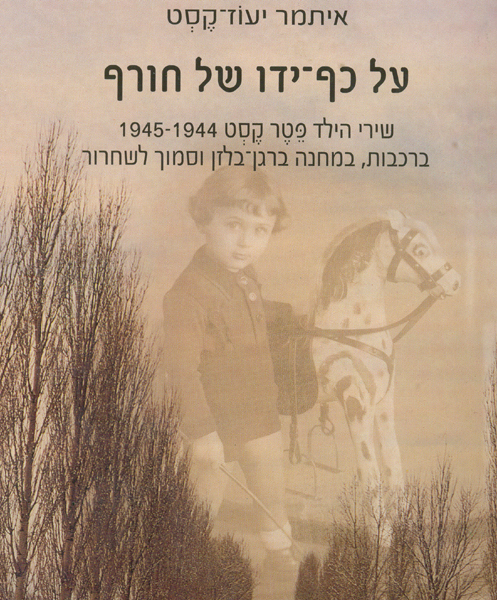

Itamar Yaos-Kest: Al Kaf-Yado Shel Choref

Introduction

Itamar Yaos-Kest was born in 1934 in Sarvash, Hungary as Peter Kest and after the Germans invaded in March 1944, he began his childhood Holocaust trauma as a boy of ten years old. Fortunately, he was surrounded by his family right through the terrible camp conditions of Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany and against all probability, both parents and the two children survived more than six months in the camp. On scraps of paper his parents procured for him, he began writing his first poems as a ten-year-old in a German concentration camp. As of 2014, Itamar Yaos-Kest lives in Tel-Aviv, husband, father and grandfather, with a large oeuvre of poetry written over the years.

The following true story he wrote as an introduction to a belated publication of his childhood poetry in 2006, all in Hebrew translation from the original Hungarian.

It is a tantalizing story of mixed emotions of the adult to the turbulent beginnings of a budding poet germinating in the pits of ‘inhuman human’ behavior.

An Exercise Book with a Black Cover1

A lined exercise book with a black cover containing short poems in rhyme, written in the blurred handwriting of a child… a few loose pages probably torn from another exercise book… and on these pages, a long poem written in the same hand but clearly indicating a soul in torment.

When did I first receive this black-covered exercise book? – I have thought about this quite a bit recently; that is, since I made peace with these poems I wrote as a child and which appear in the exercise book and on the yellowing and crumpled pages attached to the book. And then suddenly I had a flashback.

A few days after liberation from the Germans, the liberators transferred us - a group of refugees locked in train-cars who were making their way from Bergen-Belsen to the unknown, and who had just been on the verge of being exterminated – to a resort town called Hillersleben which had belonged to the administrative staff of Hitler and from which the German staff had been expelled. This was the work of the liberating American forces.

We stood in these well-appointed apartments filled with fine things – ragged, covered in lice and barely human in our appearance. Even the allied soldiers found us daunting. One o’clock in the afternoon with spring in the air and Father opened the curtains wide to look at the distant mountains enveloping the scenery. The doorbell rang but Father refused to open the door. Instead he simply continued gazing at the peaceful setting of the sun, as if to affirm: Yes, there are still these quiet, calm sunsets in the world around….

A few moments passed and we heard the shouts of a woman from the street opposite the big lounge window. “Sir, Sir, I want my expensive house crockery, porcelain and family heirlooms…” she shouted in German. It was clear that the woman had, until a few days ago been living in this apartment. Father’s eyes rested on the woman’s face and after a few moments he told her in a somewhat funny tone: “Hold on, lady… in a moment, in a moment.” With that he approached the brown wooden cupboard and began pulling out the drawers with the plates, coffee and teacups and all the other fine ware.

As he was doing this, he saw the exercise book, some pencils and an inkwell. In great excitement he turned to me with: “This is for you Peter, take these things for yourself.”

He then gathered all the good crockery in his arms and from the open window, he called out: “Madam, Madam, please receive your fine crockery…” and then added after a moment of silence, “We also once had fine crockery at home.” And with that, he threw all the fine wares out the window on the second floor to crash at the feet of the German woman who had been part of the Fuehrer’s work force. The noise of shattering plates rose up from the road below and it was as if the ringing sounds echoed through to all the streets of Hillersleben.

Tears filled Father’s eyes but they were tears of joy. He even laughed about it. I hadn’t heard him laugh like that in years.

“Did you take the exercise book?” he asked, “copy all the poems you wrote in the camp into it.”

I hadn’t enjoyed the feel of regular writing paper and good pencils and pens of the school type for a long time. I nearly forgot what they felt like.

The poems had been scribbled on torn pieces of packing paper. My parents got them from other prisoners in our hut and the neighboring hut for the price of a portion of bread in order that I could fill my time between roll calls. I also invented a game with the lice that I picked out of my clothes: me on one side and the lice on the other with battle lines drawn up between us.

Copying the poems wasn’t a simple matter for me. I felt myself resisting the poems which I did not like since they reminded me of such a bad time. And yet, I did copy them, even with some excitement, because I tried to improve my handwriting which was terrible and which had brought upon me many punishments in my Jewish-neological (reform) school back in the city of my birth, Sarvash.

So, I applied myself to copying my short poems – some of them about hunger and fear and deprivation, and others about lighthearted subjects from days gone by, but all written in an attempt to counter the awfulness of our surroundings in the hut. I noticed tears in my mother’s eyes, tears of happiness that her son looked like a pupil again in a small school. This was before she heard that her parents had been murdered by a unit of S.S. soldiers in Austria. She was devastated by this news which erased any vestige of joy in her life for years after. The atmosphere in the house was clouded for this whole span of time.

Towards the autumn of 1945, we returned to the city of Sarvash in Hungary. A short time after we arrived back Father asked me: “Why don’t you write a long poem describing the whole terrible ordeal of our deportation from beginning to end?” I shrugged my shoulders since I had no desire to recall all the suffering. We had arrived home and even father was attempting to regain his equilibrium in the new Socialist regime in Hungary.

After a while, he took two or three poems from my exercise book and without asking me, sent them to a widely-read daily newspaper in Hungary called The Hungary Independent with a description of the circumstances in which they were written. A few weeks passed and my poem Hunger appeared on the back-page of the paper with the following comment written by the editor of the paper:

“It is difficult to believe that a child of ten wrote this poem – but if this information is correct, the child is possessed of an unusual literary ability.”

This comment encouraged me besides the surprise at seeing one of my poems in print. I decided to listen to my father and his suggestion to write about our deportation in a long, rhyming poem.

This event happened close to our return, in the winter of 1945. In fact, the first lines of this long poem I wrote when we were still in Hillersleben in the expectation of returning to Hungary. But the effort involved in reconstructing the atmosphere of our deportation paralyzed me and I stopped writing.

However, back in Sarvash it was different. My new friends in the state school where my parents registered me asked me, “Where were you during the whole of last year?” And I wasn’t sure whether the question came from thinly-veiled antagonism or blatant enjoyment at my recent suffering. But I again felt the waves of antisemitism enveloping me just like before the deportation and it seemed as if nothing had changed here.

At this point, I sat myself down and wrote “Meoraot Hagerush”… from beginning to end, as if someone was writing a fictionalized nightmare or a tough documentary and all from the time perspective of a year or a year and a half. But I refused to reveal ‘the fruits’ of my labor to my friends or my teachers – as a result of the following sudden event:

My mother, when she heard about the murder of her parents in Austria, fell into a black hole of depression and slept most hours of the day away. I, on the other hand, was intent on living my life by diminishing the impact of the past and I even joined a youth movement in the framework of the new school. At a meeting around a campfire, the youth-counselor began a talk about a custom prevalent among certain groups – circumcision – and with his eyes bearing down on me, as if he expected me to provide the living example, my legs began to tremble with my heart pounding beyond its limit. I ran for my life and the long poem remained hidden in my pocket.

After a while, the family moved to Budapest in the hope that mother would emerge from her depression with the change of scenery. Father, who had a literary soul from his youth, became friendly with some literary and journalistic figures in the big city – and again passed one of my poems to a newspaper, this time with my silent acquiescence. The poem was called “A Meeting with Death.” The editor published the poem on the front page of the paper in the context of a long political article which made me very angry, also with my father.

“Why did you take the poem from me…the article is full of nonsense… and my poem…now I won’t be able to appear at school anymore…from now on, everyone will know that I’m… everyone will know that we’re… that we’re not…”

“What?” father asked in a quiet voice. “Have you been hiding the fact that we’re Jewish? Now?… After the war?” His face registered surprise. He didn’t shout at me as he returned the article to his pocket.

In fact, this event was crucial to my connection with my black-covered exercise book. I wanted nothing to do with it for many years. Even when we immigrated to Israel in 1951, I totally ignored its existence and never even thought of asking what had happened to it. I did continue writing poems but the subject matter was divorced from my Holocaust experiences, even after I started writing my poems in Hebrew. I needed very much to be just like my classmates in the Tchernichovsky High School in Netanya. And when my teachers called me ‘a kid from the Holocaust’ (with good intentions) I objected strenuously, explaining to them that my time spent in Bergen Belsen was a private matter only. Like some kind of ‘accident’ in my childhood.

Only in 1959 did the cracks in my stonewalling begin to appear. I was already married, busy publishing poems in most of the literary circles in Israel with one small publication of my work in print.

And then the following occurred. I was reading and translating a novel from Hungarian to Hebrew. The book told the story of a doctor and his family and their deportation into the German camp system from a town in Hungary. Since my own family story was so similar I began to experience acute emotional turmoil and my attempts to distance myself from Holocaust proved impossible. A deep crack suddenly pierced my personal armor and within weeks I had written and completed a cycle of poems entitled, “ORDEAL BY FIRE” –“The Bergen-Belsen Episodes.”. Their publication aroused a strong interest in the media at the time (1962) and some of the poems were included in the High School literature syllabus.

Despite these developments, I was still driven by a need to escape my past, even after writing these poems which were an engagement with my experiences albeit obliquely nuanced. It was only as a result of my wife’s pressure – a native born Israeli – that I agreed to add the sub-title, The Bergen –Belsen Episodes, an unmistakable pointer to the content of the poems.

After the poems appeared, my mother asked me if I was interested in taking back my black-covered exercise book with my childhood poems from the camp period? I was astounded by the question. I had not an inkling that she had been guarding this book all this time. I rejected her offer because it would have been as if I was permitting a rejected world entrance into my new home. And so it happened that I entered on another long period of removing the world of the Holocaust from my immediate environs. Only my mother continued to live the difficult past day in and day out. Once when she was asked about the necessity of an official Day of Holocaust Remembrance, she answered that she was in dire need of one day WITHOUT Holocaust Remembrance.

Today I know that this process of pendulum swings, engaging with and distancing from the Holocaust, is typical for children-survivors of the period. I think that it was only with my mother’s passing that this vacillating ended. All my mother’s belongings went over to my sister when she died and this included my black-covered exercise book. My sister asked me if I wanted my poems back and my stand was the same as before – I said no. I was very happy with the clause in my mother’s will which gave Yad Vashem everything in her possession that was connected to the Holocaust, including the jar of ashes which contained the bullets that killed her parents and had stood in her room all these years – the jar that clouded my early years after the Holocaust.

And then, in 1983, while I was editing a new selection of my poems, I suddenly felt a need to translate from Hungarian to Hebrew one or two of my childhood poems that had been in cold storage for so long at my sister’s. I wanted to add them at the end of the new selection in a separate section entitled “A Document”. I needed to establish a clear separation between my literary output and the natural testimony of a small child.

And thus, the exercise book finally returned to its owner. But am I the real owner? – I asked myself from time to time. The language of my writing has changed and even my name is different from the name of the boy I was…

And, in fact, what is left in me of the child Peter Kest, who scribbled line after line on torn scraps of paper in the semi-darkness in order to beat the oblivion of passing time as the lice were biting into his flesh and the epidemic of typhus was threatening all around? Only after many years did I attempt to describe in a poem, this child in Bergen-Belsen whose only playmates were the little lice busy spreading epidemics:

Game

Like the white head of a pin between the fingers

And a thin crackling sound – the boy plays early in the morn

With lice(---)

And white bedecks white – the brightness of the snow on the

brightness of the lice.

A smooth drop of blood is squeezed

And spreads on skin shivering in the freezing cold.

This is the revenge of the boy, endlessly scratching,

And he imagines himself a soldier lying in a tent on the field of battle.

He is ready for attack but

A breeze wafting through the hut

Carries the fragrance of the winter firs

Without fences and the boy feels the onset of more sleep.

(From poems written 1997, entitled The Doors of Huts Still Open Inside Me)

Indeed, the taste for play is still within me. My fingers turn the yellowing pages of the exercise book very slowly – in fact, it is well kept in a small glass case at Yad Vashem in an exhibition called “No Child’s Play.” And I know that everything I have written over more than the last fifty years all leads back to the black-covered exercise book which my mother guarded with her life, and in which the poem “Hunger” appears as a symbol of all the poems I have written since the winter of 1944.

Hunger

My stomach complains and I mumble quietly to myself:

To eat? Not to eat?

It is such a small piece of bread after all.

To drink? Not to drink?

What is there to drink? Tell me, you folk

Filthy water with blood?

Fire will I send through the land,

Curses will I aim at the heavens

And I will dream of my next meal.

Bergen Belsen, Winter, 1944

- 1.The following was written by Itamar Yaos-Kest in Hebrew as an introduction to a collection of poems written by the child Peter Kest as he experienced the Holocaust (Itamar Yaos-Kest: Al Kaf-Yado Shel Choref, published by Eked and Yad Vashem, Israel 2006, p. 7-13, translated by Jackie Metzger).