After liberation, Jewish survivors emerged from labor and concentration camps, crept carefully from hiding places, and cast off borrowed identities. They stood up and looked around at the smoking ruins and mountains of rubble that much of Europe had become while they had been incarcerated or hidden. Their first step, after evading death, was to search for family, friends and neighbors who might, like themselves, have somehow managed to remain alive in the inferno against all odds. Many decided to go back to their prewar homes, but in some places, especially in Eastern Europe, Jews met with severe outbursts of antisemitism and anti-Jewish violence. This seems ironic: if anything, there should have been sympathy for these people who had lost everything – their homes, years of their lives, and in many cases, their entire families – especially after the raw facts of the Holocaust were known.

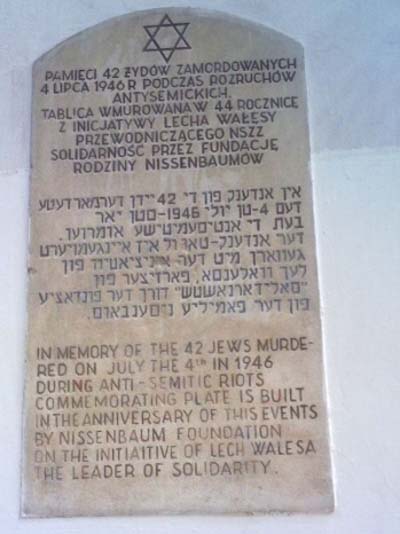

Instead, returning Polish Jews encountered an antisemitism that was terrible in its fury and brutality. The most shocking such episode was the Kielce pogrom – a violent attack in July 1946 by Polish residents of Kielce against survivors who had returned, in which 42 Jews were murdered. The Kielce pogrom became a turning point for Holocaust survivors; it was for them the ultimate proof that no hope remained for rebuilding Jewish life in Poland. The pogrom sounded an internal alarm: during the months that followed it, survivors fled from Eastern Europe any way they could. If approximately 1,000 Jews per month left Poland between July 1945 and June 1946, immediately after the pogrom the numbers spiked dramatically: in July 1946, almost 20,000 fled; in August 1946 that number swelled to 30,000, and in September 1946, 12,000 Jews left Poland.1

Yet, the murder of 42 Jews in Kielce, as monstrous and harrowing a crime as it was, was not the only story of murder in the post-war period in Poland. As many as one to two thousand Jews may have been murdered after the war by Poles.2 Kielce, however, was the proverbial "straw that broke the camel's back." Kielce reflected the stark betrayal of a Jewish community that was trying to reestablish itself, at a time when it should have received compassion and sympathy from its neighbors. Those who had survived the Holocaust only to experience murder at the hands of their own countrymen could not bear this additional tragedy.

The War and Immediate Postwar Period

In looking back at the mounting evidence of violent antisemitism in Poland during the war and immediately after it, it is clear in retrospect that the scene was being set for a great upheaval in the relationship between the Jews and their Polish neighbors, even while World War II continued.

With the war still raging in 1944, an initial committee was established to help the remnants of Polish Jewry that, it was hoped, would survive the Holocaust. In its very first protocol, dated August 11, 1944, this Central Committee of Polish Jews noted that help was needed by the Jews of Wlodawa who were being "attacked by destructive elements."3 The committee's second meeting, on August 13, 1944, was devoted to discussing the threats posed to Jewish survivors from "elements inimical" toward them. The discussion included such questions as whether mayors of towns already liberated should be asked to issue proclamations to their Polish populations requesting them to be friendly toward their Jewish citizens, and whether to inform the Catholic clergy of these threats against the Jews.4

On September 1, 1944, the head of the newly-created Bureau for Matters Concerning Aid to the Jewish Population of Poland noted that "instances in which Jews have been murdered following the departure of the Germans, which even now are recurring sporadically, are driving the remaining Jews to desperation, and a relatively large number of Jews is still afraid to come out of hiding."5 On October 27, 1944, a grenade was thrown into the building that had been occupied by the handful of Jews who had returned to the village of Losice.6 A report filed in January, 1945 emphasized that "not a week goes by in which [the body of] a Jewish murder victim is not found, shot or stabbed by an unknown assailant."7 Foreign news services were reporting at that time about the uncontrollable "pogrom atmosphere" that hung over Poland, and Poland's representatives in the Foreign Ministry acknowledged the accuracy of this description in private conversations.8

Then came the end of the war. Jews were liberated from concentration camps, labor camps and death camps, and they struggled to return home, to the places from which they had been wrenched out and deported.

Sala Ungerman went back to Poland after liberation from the camps. She had wanted to return to Klementow, but people she knew told her not to go back; Poles had killed 5 Jews there after liberation. She went to Lodz instead.9 Liba Tiefenbrun returned to Tarnow in May of 1945. She asked a railway man whether there were any Jews there. He told her "that there are a few, but that they are afraid and have to hide."10 Sara Palger-Susskind survived the Lodz ghetto, Auschwitz and a number of other camps. After the war she was given an apartment in Lodz. Hungry, she went to a grocery store where she stood on line to buy food with other survivors.

"Two Polish women who had entered after us and were still standing at the counter raked us with hostile gazes. We overheard them: 'Look, look,' said one to the other, 'how many dirty Jews are still alive. And they told us that Hitler had managed to exterminate all of them.'"11

Stories such as these were rife in Poland after the war.

And in August, 1945, one thousand elite members of the Polish Peasant Party who gathered at a theater in Bochnia for a political meeting reacted with thunderous applause to a resolution that proposed to thank Hitler for destroying the Jews and to expel from Poland all those who were still alive.12

Blood Libel Accusations

Then, in 1945, there was a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms in Poland, sparked by rumors that Jews had committed ritual murder: the age-old canard that Jews killed Christian children to use their blood for ritual purposes such as making matzo13 or wine.14 Even the Vatican accepted the ritual murder myth, writing in a memorandum that "the influx of Russian Jews [into Poland] coincided with the mysterious vanishing of Christian children."15

The first such blood libel was in Chelm in the spring of 1945: the Polish militia accused some Jews "of drawing blood 'from a Christian boy'", and tortured one of them.

The next one, escalating in terror, was in Rzeszow, in June 1945, when the mutilated body of a Polish girl who had gone missing was found in the basement of a building that was home to a number of Jewish survivors. The Polish militia searched the survivors' apartments, where they found traces of blood in a bucket, a knife, and a bloodstained shirt. Conveniently, a page from the girl's copybook and a swatch of fabric similar to that of the girl's skirt were found on a bed in one of the survivor's apartments.16 The fact that one of the survivors was a shokhet (kosher butcher) explained the blood, the knife and the shirt, but all this was irrelevant. The militiamen claimed that the girl's blood had been sucked out of her body for Jewish ritual purposes. This gave them enough of a reason to arrest all the Jews in town and even those passing through it on trains. Beginning on the morning of June 12, 1945 and continuing for the next six hours, the area of the apartment building was surrounded by a hostile crowd that clubbed and beat the Jews and threw stones at them as they were being hauled down to the police station. Police reports from the period meant to inform headquarters of important events did not include this anti-Jewish riot, as though it constituted acceptable behavior.17

A few days after the rioting in Rzeszow, a rumor that Christian children were killed in an act of ritual murder was spread in Przemysl.18 At the beginning of August, 1945, leaflets appeared in Radom and in Przemysl demanding that Jews leave the town before the middle of the month.19 Assaults on Jews occurred in Opatow, Sanok, Lublin, Grojec, Gniewoszow, Raciaz and other towns.20 On the night of August 12, 1945, someone hurled a hand grenade into a hospital for Jewish orphans in Rabka, and shots were fired at the hospital building. This occurred three times until the hospital was finally closed down.21 Five people were severely wounded in another pogrom in Chelm that lasted eight hours. The report of the Section for Aid to the Jewish Population of August, 1945 stated, "[T]his period is marked by increasingly frequent organized assaults against the defenseless Jewish population and the number of Jewish victims grows daily."22 News of attacks on Jews was coming in almost every day, and the threat of looming violence was bolstered by antisemitic propaganda that appeared in underground newspapers and flyers.23 Perpetrators of the anti-Jewish actions were seldom punished.24

Jews were urged to move to the bigger cities; it was felt that in the cities they would be more secure since the overwhelming majority of attacks occurred in villages and small towns of central Poland.25 However, rumors of blood libels made their way to the cities as well.

In Krakow, a Jewish woman was arrested in late June for allegedly attempting to kidnap and murder a Polish child. The arrest sparked dangerous rumors. Tension mounted throughout the summer, as the rumor circulated that the bodies of thirteen murdered Christian children had been discovered. By the beginning of August, the number of rumored corpses had grown to eighty. A mob gathered every Friday night and Saturday outside Kupa Synagogue in Kazimierz to throw stones at the building and at the Jews praying inside while screaming, laughing and taunting, behavior that did not stop even after guards were posted near the synagogue.26 Finally, the situation reached the boiling point. On Saturday, August 11, 1945, a 13-year old Polish boy ran out of Kupa Synagogue screaming "Help! They want to murder me!"27 The crowd of about 60 Poles outside broke into the synagogue looking for the Christian children's corpses. They destroyed and plundered the synagogue, tore Torah scrolls, and attacked not only the Jews who were there, but other Jews in the area. The synagogue was set on fire. Roza Berger, an Auschwitz survivor, was murdered; there may have been as many as four other casualties, but this remains unclear.28 The violence spread throughout the Kazimierz quarter of Krakow; robberies and beatings were recorded in a dozen different apartments. Five Jews were wounded, among them Hanna Zajdman. She gave an account of her experience to the Jewish Historical Commission on August 20, 1945. According to Zajdman's account, even in the ambulance to the hospital the wounded were called "Jewish scum" by the soldier and the nurse who accompanied them. Once at the hospital they were beaten by other patients and by soldiers. They were threatened repeatedly, even by nurses, who said that, "they were only waiting for the surgery to be over in order to rip us apart."29 The scourge of the pogroms had reached the big city.

The Kielce Pogrom

As shocking as the Krakow pogrom was, the Kielce pogrom, which came almost a year later, was even more notorious. This time, 42 Jews were killed. The pogrom took place in broad daylight and with the participation, or at least the indifference, of the local police, the Security Service and the army.

In 1939 there were approximately 24,000 Jewish inhabitants in Kielce, or one-third of the town's population. Almost all of them were murdered during the Holocaust, most at Treblinka. In the summer of 1946, about 200 Holocaust survivors were living in Kielce; some had returned home, others were just passing through. Most lived together in the vicinity of a house in the city at 7 Planty Street as they searched for friends and relatives. The building also housed various Jewish institutions including a newly-created Jewish Committee, a religious congregation, a kibbutz and an orphanage.

During the summer of 1946 rumors about disappearing children began to spread in Kielce. Leaflets were posted on walls and telephone poles with announcements about missing children, and priests read them aloud at mass.30 According to one Pole from Kielce who was a teenager at the time, when someone disappeared the kids at school would say, "Antek Wawszczyk has been taken for matzos...Gienek Bienkowski has been taken for matzos...."31 This was a routine reaction.

"In a poor working family, postwar times, right – the boy isn't home, so he isn't home, he's run off somewhere, God knows where he's gone, the usual. A day or two before [the pogrom] [...] they started coming back. What did they say to their Daddies, what did Gienek say to his Daddy? 'They took me to this apartment and there they beat me and turned me around in a barrel studded with nails for matzos, because they were drawing my blood for matzos. And then they let me go.'...That's the legend of kidnapping for matzos at Passover; tell me another, in July, ... for Passover! – knuckleheads, but who would have known?"32

The ease with which Polish children could use this excuse shows how frighteningly widespread the blood libel accusation phenomenon was at that time.

A nine-year-old named Henryk Blaszczyk disappeared from Kielce on July 1, 1946. Without telling his parents, he had hitched a ride back to Pielaki, the village where the family had lived until six months earlier, so that he could see his old friends and pick some cherries. His parents had reported him to the police as missing; his father had posted three announcements about his missing child. After two days Henryk returned to Kielce, loaded with cherries and excuses.

"His family and neighbors asked him where he had been. In response, he told a story about an unknown gentlemen whom he had met in Kielce. He asked him to deliver a parcel to some house and after that he put the boy in a cellar. With the help of another boy who was also there, Henryk escaped on July 3. Obviously, the story was told by the boy to avoid punishment, but the neighbors and the boy's parents believed it. But two neighbors who were at the Blaszczyks' home when Henryk came back had questions. One asked the boy whether the gentleman he described was a Gypsy or a Jew, and the boy replied that the unknown gentleman did not speak Polish and that he therefore had to be a Jew. However, in response to a similar question asked by another neighbor, the boy merely replied that he was put in a cellar by a man without giving any information about his nationality. In other words, two persons suggested to little Henryk that Jews could have been the perpetrators of his abduction, and this information was reported to the police station on the evening of July 3."33

The next day, July 4, 1946, at about 8 a.m., Henryk, his father Walenty, and one of the neighbors went to the police station to report the "abduction." On the way, they passed the building at 7 Planty Street where the Jewish Committee was located and the Jewish survivors were living. The neighbor apparently suggested to the boy that this was the house where he had been held, and Henryk not only agreed, but also pointed to a man in a green hat standing near the building and identified him as the man who had lured him in and put him in the cellar.

The police treated Henryk's story as truthful, and dispatched policemen to Planty Street. Planty Street is a small street in the center of town, and the police patrols attracted the attention of the Kielce residents. Moreover, the policemen on their way to the building told people that Jews had kidnapped the boy. The young Jewish man pointed out by the boy as the culprit, Kalman Singer, was arrested, and the police started searching for the place where the boy had supposedly been held. People started to congregate in front of the so-called Jewish house. This worried the Jewish families inside. Dr. Severyn Kahane, the chairman of the Jewish Committee in Kielce and an inhabitant of the building, went to the police station to plead for Singer's release. He was worried that a "misfortune might come about" if Singer was not let go.34 Singer, meanwhile, was interrogated and beaten at the police station. While at the station, Kahane attempted to explain to the police that the boy could not have been kept in the cellar against his will because the building had no cellar; the Silnica creek ran just outside the house and the ground was too wet for a cellar.

The police at the scene quickly understood that the house indeed had no cellar, leading Henryk to change his story. He now claimed he had been kept in a shed or in a doghouse. No matter – the search of the house by the policemen convinced the crowd that the rumor about Polish children being kept there was true. The crowd grew to more than fifty people.

The next major factor in the escalation at Planty Street was the intervention by the head of the secret Security Police and his Soviet advisor, who believed that the incident at the Jewish house was a political provocation which fell under their political jurisdiction. They sent State Security officers to the building. Army troops joined the police patrols and the State Security officers at about 10 a.m. About one hundred soldiers and five officers arrived at Planty Street. Because they had received no instructions, they came to believe that they were there to look for the murdered children. With the arrival of the troops, tensions rose very quickly.

When the soldiers and policemen entered the building, members of the civilian mob, which had been growing for almost two hours and had become unruly, forced their way in along with the police, screaming things like, "Let us in, we'll make them pay for it ourselves."35 The entry of the policemen and the soldiers into the Jewish house was the catalyst for the beginning of the pogrom.36The militia dragged Jewish victims out of the house and passed them to the mob. One of the soldiers shouted that he had seen corpses of four children in quicklime; a policeman screamed that his child was dead and in this house; and another officer provoked the mob by yelling, "Look for the kids!"37 Jews were shot and beaten. The first casualty, a tinsmith named Berel Frydman, was thrown out of a window. Other Jews were led outside where the mob killed them cruelly. Ryszard Salapa (one of the policemen) recalled: "The military led Jews out of apartments and people began hitting them with everything they could. The armed soldiers did not react. Some returned to the building to lead other Jews outside."38 Many of the pogrom perpetrators were drunk; others, fatigued by the violence, went to have a drink and then came back to join the mob.39 At about 11 a.m. Seweryn Kahane, the chairman of the Jewish Committee in Kielce, was shot in the back and killed while calling for help.

At about 12:00 the army managed to push the crowd back from the square facing the Jewish house. The momentary lull in the violence allowed some of the wounded to be taken to the hospital. But very soon about 600 workers arrived from the Ludwikow steel mill nearby, armed with bats, crowbars and stones. They were apparently recruited by Henryk Blaszczyk's uncle, who worked at the foundry as a watchman. According to eyewitnesses, nothing could be done to save the Jews inside the building or on the square once the workers came.

Though the commanders of the State Security Service were in the area, they took no steps to stop the massacre. Neither did the military or the local political leaders from the Polish Workers' Party. Around 2 p.m. five priests went to Planty Street to try to convince the people to go home. The priests warned that the soldiers would use their weapons, but the soldiers replied that the Polish army would never shoot at Poles.40

The pogrom lasted until about 3 p.m.; a curfew was finally established by army troops from Warsaw that arrived in Kielce at about 3:30 p.m.

The pogrom spilled over into the city itself as well. Groups of Poles walked around town searching for Jews. Anyone who looked vaguely Semitic was in danger. According to one testimony, "Some man was walking past; they said he was a Jew, so I hit him. An officer said that you can't hit him, that he's not a Jew. If I had known, I wouldn't have hit him."41 An assault on a Polish woman who looked Semitic was deemed a "mistake", while the only thing that saved another woman from being beaten – the crowd was already surrounding her, screaming "Jewess!" – was the fact that her child had blond hair.42 The train station turned into a death trap, with as many as seven Jews murdered – some with heavy iron objects such as rail sections or pieces of railroad equipment that crushed their skulls.43

Regina Fisz was in her apartment at 15 Leonarda Street with her newborn baby boy in the early afternoon of July 4, 1946. A group of four men knocked on the door of her apartment, identifying themselves as policemen; consequently she let them in. Only one of the three was actually a policeman; he had been approached by one of the others with a spontaneous proposition to kill the Jews living on Leonarda Street and steal their property. The four ordered Regina, her baby and Abram Moszkowicz, who was also in the apartment, to come with them.

A crowd gathered outside and followed closely behind. As the four marched their intended victims along, they tried to figure out how to kill them – they couldn't risk shots being heard. The policeman, by the name of Mazur, saw a truck, stopped it and approached the driver, telling him they had Jews they wanted to take out and kill. The driver agreed, asking for a thousand zloty. The policeman said, "It’s a deal." The crowd was getting restless – they wanted to beat the Jews, but two of the other abductors calmed them down telling them, "We ourselves will do them.” The four, with their victims, climbed into the truck and drove to a place in the forest eight kilometers away. During the ride, Regina Fisz and Abram Moszkowicz continually begged their abductors to spare their lives, offering to pay great sums of money. The four men decided against it – it was easier just to take the few thousand zloty and some other valuables the Jews had with them. Regina tried to flee and was shot dead from behind. Moszkowicz escaped with the infant, but dropped the baby while running. The men killed the newborn with a bullet in the head. (Moszkowicz collapsed in a field of rye and was later beaten unconscious by another group of young Polish men). They buried the bodies and then returned to Kielce where, together with the truck driver, they went to a restaurant, drank some vodka and ate a good meal which cost them one thousand zloty.

"Perhaps the most arresting moment in the story...comes when the policeman Mazur hails a passing truck in the street, tells the driver that he needs transportation to kill some Jews, and the driver agrees to offer his services for a fee. One does not know what is more startling in this brief encounter – the gall of a policeman in stopping a random stranger to make such a proposition, or the callousness of the stranger who accepts such a proposition on the spot.[...] it was a perfectly comprehensible exchange between strangers in Poland in Anno Domini 1946."44

A resident of Kielce testified about the brutality he saw in the city that day. "I would like to mention that as a former prisoner of concentration camps I had not gone through an experience like this. I have seen very little sadism and bestiality of this scale."45 The day after the pogrom, this description was written by an eyewitness:

“... The sight of the large, modern apartment house on Planty Street was the ultimate in ruthless havoc. ... The immense courtyard was still littered with bloodstained iron pipes, stones and clubs, which had been used to crush the skulls of Jewish men and women. Blackening puddles of blood still remained. ... Blood-drenched papers were scattered on the ground — sticky with gore, they clung to the earth though a strong wind blew through the yard....I picked up some...These were letters addressed to the victims by their relatives in Palestine and Canada, and the United States .”46

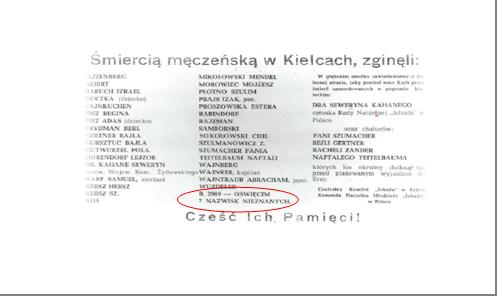

Forty-two Jewish Holocaust survivors were killed in the pogrom, as well as two Poles. The former group included a pregnant woman, an infant, a small child, and a number of 16- and 17-year old Zionists who were staying at the Kielce "kibbutz" while they prepared to leave Poland for Palestine. Some of the victims could be identified only by their family names, but seven of them could not be identified at all – perhaps because they had so recently returned to Kielce that no one yet knew their names; perhaps because they were just passing through on the train. The list of victims also included one person who could be identified only by the number from Auschwitz tattooed on his arm. These details can be seen from the death notice, below, in Polish.

"The number of victims...does not reflect the atrocities that accompanied the pogrom. Eyewitness reports recall the shooting of innocent victims, the police throwing young girls out of third-story windows, after which they were beaten to death by the crowd below, and the stoning to death of a young man. Moreover, although the violence was played out mainly at the building on Planty Street and its immediate vicinity, there were murders of individual Jews throughout the city as well as on trains passing through Kielce on that day." 47

On July 8, 1946, the victims of the pogrom, including Regina Fisz and her infant, who were exhumed from their forest graves, were buried at the Jewish cemetery in Kielce.

No Single Explanation

Almost seventy years after the Kielce pogrom, there is still no clear explanation for the events that occurred in Kielce, in Krakow or in a dozen other cities in Poland after liberation. There are several theories about why the Kielce pogrom took place, all of which are based on explanations much more complex than simple antisemitism or indiscriminate postwar lawlessness. It is beyond the scope of this article to examine them in depth; some remain highly controversial and have been written about at length, many in the sources cited here.

One thesis suggests that the communist party was responsible for the pogrom. According to this narrative, the Kielce pogrom was an orchestrated provocation by the Polish secret police and the Soviet NKVD. It was meant to distract the Poles from the falsified results of a referendum held shortly beforehand, that was seen as unofficially deciding that the Polish citizenry supported communism.

According to another narrative, the ruling Polish Workers Party and Polish Socialist Party orchestrated the pogrom for propaganda purposes in order to compromise the opposition party and the armed anticommunist underground resistance.

A common theory is that of "Zydokommuna" – the idea that all Jews are communists. Postwar Polish society was dominated by strong anti-communist sentiment. Zydokommuna equated Jews with communism, thus making them the enemy. This feeling was supported by the Church: the Polish primate, Cardinal August Hlond, not only refused Jewish pleas to condemn anti-Semitism prior to the pogrom, but afterwards he charged that the Jews led the effort to impose communism on Poland, and because of this they had only themselves to blame.48 The point was seconded by the bishop of Kielce, who suggested that Jews had actually orchestrated the pogrom to persuade Britain to give them Palestine.49

The theory put forth by Jan T. Gross in his groundbreaking book, Fear, posits that Poles murdered Jews because they felt so guilty about the role they had played in the Jewish tragedy. Based on the maxim that it is human nature to hate the man whom you have injured, Gross concluded that "[w]herever Jews had been plundered, denounced, betrayed, or killed by their neighbors, their reappearance after the war evoked this dual sense of shame and contempt. [...] And as long as Polish society was unable to mourn its Jewish neighbors' deaths, it had either to purge them or to live in infamy."50

It is accepted that at least some of the virulent antisemitic behavior of the Poles stemmed from their concern that Jews would take back their prewar houses and businesses which the Poles had opportunistically plundered. In this regard, it is interesting that of 13 murders of Jews in Kielce province in June 1945, fully 10 of them were related to the wartime takeover of Jewish property.51 In addition, as discussed above, little Henryk Blaszczyk himself never said that his "abductor" was a Jew until a neighbor suggested this explanation; this neighbor, a man named Antoni Pasowski, had taken over two houses in Kielce that had belonged to Jews before the war.52

"...[W]hen attacking Jews in order to get rid of them once and for all, people were not acting out their vampire fantasies or their Judeo-Communist fantasies, nor were they acting on beliefs and attitudes inculcated by the Nazis; they were defending their real interests, quite often premised on murky deals or outright criminal behavior."53

Some have attributed the callousness of the Poles in the face of mounting anti-Jewish violence54 to the corrupting influence of Nazi propaganda and the murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust. Edmund Osmanczyk, a Polish writer, described "the generation infected by death".55 The Polish writer Stanislaw Ossowski wrote, after the pogrom, "The inability to be appalled by the crime is in large measure...a result of wartime training: the murder of Jews had ceased to be something extraordinary. Why were those people supposed to be concerned with the death of forty Jews when they had grown accustomed to the idea that Hitler had killed them by the millions?"56

Yet, it must be remembered that we are speaking here about the murder of innocent human beings. All the explanations in the world cannot change that fact or justify the crime.

Whatever the explanation as to why it happened, it cannot be refuted that the Kielce pogrom was a watershed event. For the Jews who had somehow survived the Holocaust, the pogrom confirmed that Polish antisemitism was still alive and well; it was shocking evidence that a "profound abyss" existed between the Polish and Jewish communities.57 Jews who had hoped to return and to rebuild their lives in Poland no longer had any hope of doing so.

Until July 4, 1946, Polish Jews cited the Holocaust as their main reason for emigration: they felt that it was impossible to live in what had become, for them, just a giant cemetery. After the Kielce pogrom, the situation changed dramatically: Jewish and Polish reports spoke of an atmosphere of panic among the Jews in Poland. The presence of the militia and the army had not kept them safe, had not prevented Jews from being murdered in cold blood.

Even after all the anti-Jewish violence that came before it, the Kielce pogrom was the single event of violence with the greatest resonance in postwar Europe. It led to mass flight from Poland and Eastern Europe. Many of the survivors wound up in Israel, others immigrated to America and other countries. One thing is clear: after the Kielce pogrom, the face of Jewish life in Europe was completely changed.

- 1.Bożena Szaynok, "The Jewish Pogrom in Kielce, July 1946 - New Evidence". Intermarium 1:3, accessed July 16, 2015.

- 2.The consensus seems to be that at least 1,000 Jews were murdered. Jan T. Gross leans towards the number 1,500; Dr. Lidiya Milyakova places the number between 1500-1800; and Joanna B. Michlic estimates that 2,000 Jews were murdered by Poles postwar. David Engel, in "Patterns Of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946", Yad Vashem Studies Vol. XXVI (1998), p. 32 estimates a much lower, more conservative number, based on the earlier work of Lucjan Dobroszycki. However, historians recognize that any numbers used may be weak because anti-Jewish violence resulting in death was selectively reported and recorded.

- 3.Jan T. Gross, Fear. Antisemitism in Poland After Auschwitz: An Essay in Historical Interpretation (New York: Random House, Inc., 2007), p. 31.

- 4.Ibid.

- 5.David Engel, "Patterns Of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946", in Yad Vashem Studies Vol. XXVI, pp. 43-85, p. 2/39, accessed July 16, 2015.

- 6.Ibid., p. 33/39.

- 7.Ibid., p. 3/39.

- 8.Ibid.

- 9.Gross, Fear, p. 32.

- 10.Ibid.

- 11.Sara Palger-Susskind, "The Shattered Hopes" in Return to Life – The Holocaust Survivors: From Liberation to Rehabilitation, Museum Study Kit (Haifa: Beth Hatefutsoth, Beit Lohamei Haghetaot and Yad Vashem, 1995), p. 16. Her name is also spelled Sara Plager-Zyskind.

- 12.István Deák, Jan T. Gross, Tony Judt, eds., The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), p. 112.

- 13.Matzo is unleavened bread, eaten by Jews during the Passover holiday.

- 14.The first recorded blood libel occurred in 1144 in Norwich, England, but the accusation that Jews kill Christian children to use their blood for ritual purposes has probably been around since ancient times.

- 15.Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, "Communitas of Violence: The Kielce Pogrom as a Social Drama" in Yad Vashem Studies , Vol. 41:1 (2013), David Silberklang, ed., p. 26, citing Arieh Kochavi, Post-Holocaust Politics: Britain, the United States and Jewish Refugees, 1945-1948 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), p. 161.

- 16.Gross, Fear, p. 75.

- 17.Ibid., p. 79.

- 18.Anna Cichopek, "The Cracow Pogrom of August 1945: A Narrative Reconstruction," in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath (Newark: Rutgers University Press, 2003), p. 222.

- 19.Ibid.

- 20.Ibid.

- 21.Ibid.

- 22.Ibid.

- 23.Bożena Szaynok, "Antisemitism in Postwar Polish-Jewish Relations" in Robert Blobaum, Antisemitism and its Opponents in Modern Poland (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), p. 271.

- 24.Ibid.

- 25.David Engel, "Patterns Of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946".

- 26.Anna Cichopek, "The Cracow Pogrom of August 1945: A Narrative Reconstruction," in Joshua D. Zimmerman, Contested Memories, p. 225.

- 27.Ibid.

- 28.Cichopek, p. 224. Cichopek notes that in an archival photo of a funeral there were five coffins visible, thus suggesting that there might have been five fatalities. Other historians dispute this.

- 29.Gross, Fear, p. 82.

- 30.Tokarska-Bakir, "The Kielce Pogrom as a Social Drama," p. 32.

- 31.Ibid.

- 32.Ibid. The holiday of Passover generally falls out in April or in the early spring, which is why this witness points out that the blood libel was inappropriate in July.

- 33.Bożena Szaynok, "New Evidence", accessed July 20, 2015.

- 34.Gross, Fear, p. 84.

- 35.Tokarska-Bakir, p. 37.

- 36.Ibid. , p. 38.

- 37.Ibid.

- 38.Szaynok, " New Evidence", accessed July 20, 2015.

- 39.Tokarska-Bakir, p. 40.

- 40.Szaynok, "New Evidence", accessed July 20, 2015.

- 41.Tokarska-Bakir, p. 40.

- 42.Ibid.

- 43.Gross, Fear, p. 110-111.

- 44.Ibid., p. 108.

- 45.Szaynok, "New Evidence", accessed July 20, 2015.

- 46.S. L. Schneiderman, Between Fear and Hope (New York: Arco Pub. Co., 1947), p. 92.

- 47.Szaynok, "Antisemitism in Postwar Polish-Jewish Relations," p. 272.

- 48.David Margolick, "Postwar Pogrom: Review of Fear" in the New York Times Review of Books, July 23, 2006, accessed July 20, 2015.

- 49.Ibid.

- 50.Gross, Fear, p. 258.

- 51.Ibid., p. 269.

- 52.Tokarska-Bakir, "The Kielce Pogrom as a Social Drama," p. 33, n. 39.

- 53.Gross, Fear, p. 247.

- 54.For instance, both Gross and Tokarska-Bakir discuss the fact that the Polish "masses" were unwilling to publicly condemn the Kielce crime. See, e.g., Tokarska-Bakir at p. 54, Fear at pp. 120 et seq.

- 55.Szaynok, "New Evidence", accessed July 20, 2015.

- 56.Szaynok, "Antisemitism in Postwar Polish-Jewish Relations," p. 271.

- 57.Ibid., p. 272.