Although the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is the most celebrated act of armed resistance during the Holocaust, this article will focus on two lesser-known, but very important, acts of armed resistance: those in the ghettos of Krakow and Bialystok.

Just as there was no uniformity among the German-created ghettos of Europe with respect to the degree of their isolation, their establishment, their physical circumstances, and other facets of ghetto life, there was no uniformity among the ghettos with respect to armed resistance. While in Warsaw and in other ghettos resistance occurred inside the ghetto, in Krakow, resistance occurred outside. While in Warsaw the only option was to fight; in Bialystok the option of escaping to the woods was a viable one. There is no single model; developments were mostly determined by local conditions and the personalities of the leaders of the resistance, and these differed from place to place.1

Krakow

On the eve of World War II, the Jewish population of Krakow was approximately 60,000, constituting about one quarter of the city's population. The German army occupied Krakow in the first week of September, 1939 and in October, 1939, Krakow became the capital of the Generalgouvernement.

Rules and restrictions with which we are now familiar began to be passed against the Jews: they were forced to report for manual labor beginning in October, 1939; they were required to form a Jewish council in November, 1939; they were forced to wear a Star of David2 for identification beginning in December, 1939; they were required to register their property; and, in March, 1941, they were enclosed in a ghetto. Unlike in other places, however, where Jews were brought from the countryside and concentrated in the city, in Krakow the Germans actually expelled thousands of Jews to the surrounding countryside. Because the seat of the Generalgouvernement was in Krakow, the Germans wanted to cleanse the city of its Jews. As such, by the time the ghetto was established and closed on March 20, 1941, only about 20,000 Jews remained in the city.

The Germans concentrated the Jews in a ghetto that was very small and was constantly being decreased in size. Deportations from the ghetto began in June, 1942, when about 7,000 Jews were taken out of the ghetto. About 1,000 were murdered in the nearby Plaszow labor camp; 6,000 were taken by train to the Belzec death camp and murdered there. Another deportation occurred on October 28, 1942 when an additional 6,000 Jews were sent to Belzec. Hundreds of people were shot in the ghetto during these very violent aktions3 and deportations.

Youth movements had been operating in Krakow since before the German occupation, and had continued to operate in the ghetto. Generally, these groups were concerned with upholding and teaching their values to their scouts; depending on the principles of the movements – some were Communist, others Socialist, still others Zionist – activities were centered around education and self-fulfillment. The Zionist youth movements concentrated on Zionist ideals like agricultural training in preparation for life in Palestine, which was their ultimate goal. The Akiba youth movement was the biggest Jewish youth movement in prewar Krakow.

In the ghetto, the youth movements continued with their educational activities. By the fall and winter of 1941, couriers of the youth movements began to spread the word about the mass murders in Ponary, near Vilna in what had been eastern Poland. Rumors reached the youth movement networks of a death camp near Lodz, in western Poland. By the spring of 1942, information was spreading of the deportations from Lublin to the death camp at Belzec. As this information was assimilated, the character of these youth groups began to change. The Akiba youth movement had begun to think about the possibility of obtaining weapons and sending its members to the forest to fight the Germans from the beginning of the occupation, but their initial forays into the forest resulted in betrayal and the death of the scouts. The group decided to concentrate its activities in the city for the time being,6 and to begin training in the use of weapons on a farm in Kopaliny, outside Krakow, that had been used for purposes of hachshara7. The group continued to meet in private homes and provided some sort of refuge or comfort for its members, singing songs and having ideological discussions and trying to continue some sort of normalcy while surrounded by chaos and fear.

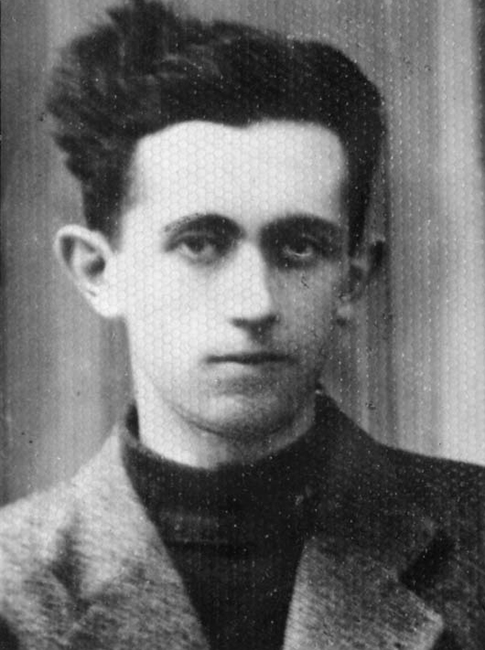

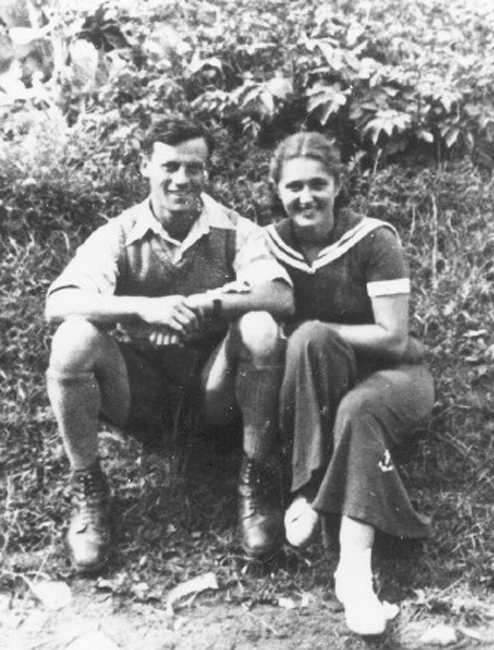

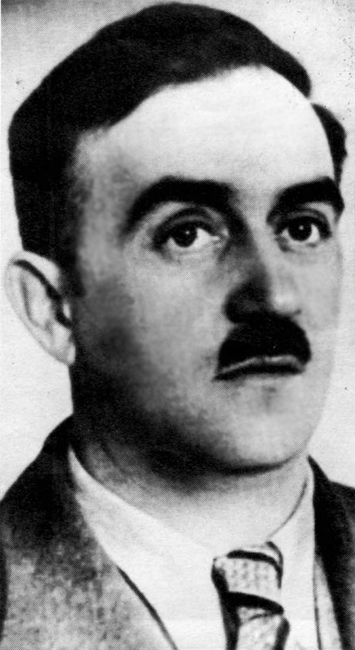

After the June, 1942 deportation, a dentist named Bachner managed to succeed in escaping from the cattlecars headed for Belzec and returned to the ghetto with the information that the camp there was not a labor camp, as the Jews had been told, but an extermination camp.8 This information was confirmed by Polish train workers, who received their information from Poles who lived in close proximity to Belzec.9 In the October, 1942 aktion, many families were deported from the Krakow ghetto. Now-homeless members of Akiba, many of whom had lost families, found shelter at 13 Jozefinska Street, in Krakow, and this became a kind of meeting place for the group, and also a launching point for attacking German soldiers in order to get weapons. They reported to the leaders of the movement, Aharon ("Dolek") Liebeskind and Shimshon ("Szymek") Draenger. Even before the October aktion, Dolek and Szymek had discussed the rumors of extermination that were reaching them from other places in the east. Gola Mire, a member of the Communist underground, the P.P.R., urged them to initiate an active, armed struggle. Gola had moved throughout Poland, from Lwow to Warsaw to Bialystok, and had come to the conclusion that the Jews were in a race against time and must act quickly to avoid annihilation.10 To that end, Akiba's leadership forged a united front together with other youth movements – Dror-Freiheit (headed in Krakow by Abraham "Laban" Leibowicz), HaShomer HaTzair, HaShomer HaDati, and others, that would be called HeHalutz HaLochem, Hebrew for "the Fighting Pioneers." The alliance was established in August, 1942.

Jozef Wulf, a member of Akiba, wrote:

None of us had received any schooling in arms or in organizing; nor did any of us have military experience. We did not have much confidence in our own strength, and at first we did not even consider it possible to link up with any of the Polish fighting organizations already in existence.11

At first, the Akiba leadership met at the apartment at 13 Jozefinska Street, located in the heart of the ghetto. But sometime in the fall of 1942, the Akiba leadership took the strategic decision to close down the apartment in the ghetto, and to move the resistance operations outside of the ghetto. Uppermost among the factors in this decision was the fear of collective punishment: the ghetto was very small, and the leadership understood that if armed action was taken against the Germans from inside the ghetto, the rest of the ghetto would be punished.12 The final decision was to operate from outside of the ghetto and, in addition, to disguise the operation so that it would not look like the work of the Jewish underground.

It is not easy to describe all the obstacles that had to be overcome in order to organize a Jewish resistance under Nazi occupation. Our work was a hundred times more difficult than the work of any other resistance group, because we had to conceal not only our underground activity but also, and even more urgently, our Jewish identities. Hence it may be said that the first thing the leaders had to do was to deny even to themselves the impossibility of the task before them, and to act in spite of the overwhelmingly unfavorable odds. 13

The decision to carry out an armed operation against the Germans from outside the ghetto was the culmination of hours of agonized discussion. The leaders of the underground faced painful dilemmas. Among them was the basic question: what were they fighting for? They had no illusions that they were fighting to achieve a military victory, because that was impossible. As such, was their purpose to avenge the deaths of innocent Jews? To rescue themselves and their movement? Or to fight to save Jewish honor?14

Dolek Liebeskind is credited with the phrase that became a rallying cry – on November 20, 1942, at one of the Friday evening dinners traditionally held by the members of Akiba to "greet the Sabbath bride"15, Dolek said they would fight for the sake of "three lines in history," if only to show that "Jewish youth did not go like sheep to the slaughter."16 The occasion became known poetically by the members of the group as "the Last Supper", because they understood they were greeting the Sabbath all together as a group for the last time. They all knew there was not much chance that they would survive.

In conjunction with Iskra ("Spark"), a movement led by Zvi Hersch Bauminger and aligned with the Polish Worker's Party (the P.P.R.), the Fighting Organization carried out a daring action against the Germans.

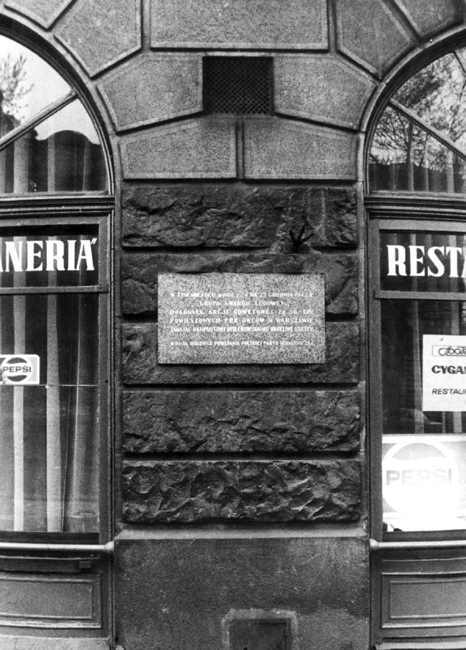

On December 22, 1942, when many German officers were in the city of Krakow shopping for Christmas presents to send home to their families, celebrating the upcoming holiday in cafés and attending the theater, the Jewish underground staged a surprise attack on certain of the places where they knew the Germans would gather. In order to make the attack look as though it had been carried out by Polish partisans, the Jewish fighters hung a Polish flag on the bridge over the Wisla River, left a wreath of flowers on the statute of Adam Mickiewicz, one of Poland's national poets, and distributed leaflets calling for an uprising against the Germans, among other things. In order to add to the chaos and panic in the city, the fire department was called from different locations simultaneously.

The underground attacked several cafés and German meeting places, but the heaviest damage was done at the Cyganeria Café, a place frequented by German officers, where it is estimated that seven to twelve Germans were killed.17 The identities of the Jewish fighters were successfully camouflaged; in fact, the operation was so daring that many Poles in the city were convinced that the Polish underground, or even Russian paratroopers, had executed the attack.18

The operation was a great success, and the turmoil that was created in its aftermath was a slap in the face of the German authorities. However, these authorities would not let such a daring deed go unpunished. Ultimately, most of the underground members were arrested by the Germans and many were killed. But Krakow was the first large ghetto to establish that the idea of armed resistance could be a reality.

The remainder of the Krakow ghetto was liquidated in March, 1943. Most of the Jews of the ghetto were finally sent to Auschwitz.

Bialystok

Many factors distinguish the Bialystok ghetto uprising from the situation in Warsaw and Krakow; perhaps the most important of these was the unique relationship between the underground fighters and the head of the Judenrat, as well as the ghetto's relationship with him. One of the reasons that the planned uprising in Bialystok did not succeed to the extent the Warsaw uprising did was because an alternative authority to the Judenrat was never established.

The Judenrat in Bialystok, under the acting leadership of Efraim Barasz19, enjoyed the trust of most of the ghetto population, on the one hand, while successfully appeasing the Germans, on the other hand. Barasz had been a respected Zionist and community leader before the war. His leadership was consistent and assertive, which contributed to the stability of life in the ghetto. Barasz's position vis a vis the Germans was based on his belief that the Germans would allow the Jews to live if they could be turned into a cheap, vital labor force – this way they could serve the Nazis' economic interests. Though the leaders of Judenraete in other ghettos also ascribed to the philosophy of "survival through work," Barasz's likability and personal prestige made his policies more acceptable to the ghetto public (unlike Rumkowski in Lodz, and Gens in Vilna).

Bialystok was among the territories annexed by the Soviet Union under the Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement, so that the war did not really reach Bialystok until the Germans invaded the area in June, 1941. The Germans arrived in Bialystok on June 27, 1941. Waves of violence followed. The Germans locked up between 800 and 2,000 Jews in the Great Synagogue of Bialystok. After they were forced inside, the synagogue was drenched in fuel and set on fire. Grenades were thrown at the building, and as the synagogue and the surrounding homes and buildings burned, almost all inside were burned alive. Within two weeks of the German's occupation of Bialystok, almost 7,000 Jews were murdered. And then, once the initial wave of murder was finished, on July 26, 1941, a Jewish ghetto was established.

The next 15 months of the ghetto's life were a period of calm where the ghetto began to work and settled into a routine. Barasz's slogan of "salvation through work" seemed to be an accurate prediction; the Jews made themselves useful to the Germans, and the Germans no longer murdered them. The philosophy was so logical that it was difficult to challenge – the Judenrat seemed to have made the ghetto so essential to the German war effort that the Germans would not dare to destroy it. The fact that the ghetto was calm and quiet convinced the ghetto population that Barasz and the Judenrat were correct, and this contributed to their credibility. The Bialystok ghetto became the largest ghetto in the area, with approximately 40,000 Jews – a figure that stayed constant through the end of 1941 and all of 1942 despite the surrounding annihilation.

In the meantime, in Vilna, Abba Kovner and his youth movement were coming to the conclusion that the disappearance of thousands of Vilna Jews and the murders at Ponary were symptoms of a German plan to exterminate all the Jews in Europe. Not everyone agreed.20 Mordecai Tenenbaum, head of HeHalutz-Hatzair-Dror in Vilna, saw the killings at Ponary as an isolated, local incident that would not occur elsewhere. He believed that the youth movement members should be transferred out of Vilna to places that were quiet, where they could regroup. Tenenbaum was convinced that Bialystok was one such place, and that it would be spared the fate of Vilna.21 As a result, Tenenbaum arranged for youth group members to move to Bialystok with the help of Sergeant Anton Schmid, an Austrian who was sympathetic to the Jews. Schmid actually transported members of the youth group from Vilna to Bialystok. He was arrested for helping these Jews in January, 1942, and was executed on April 13, 1942. Schmid was recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations on December 22, 1966.

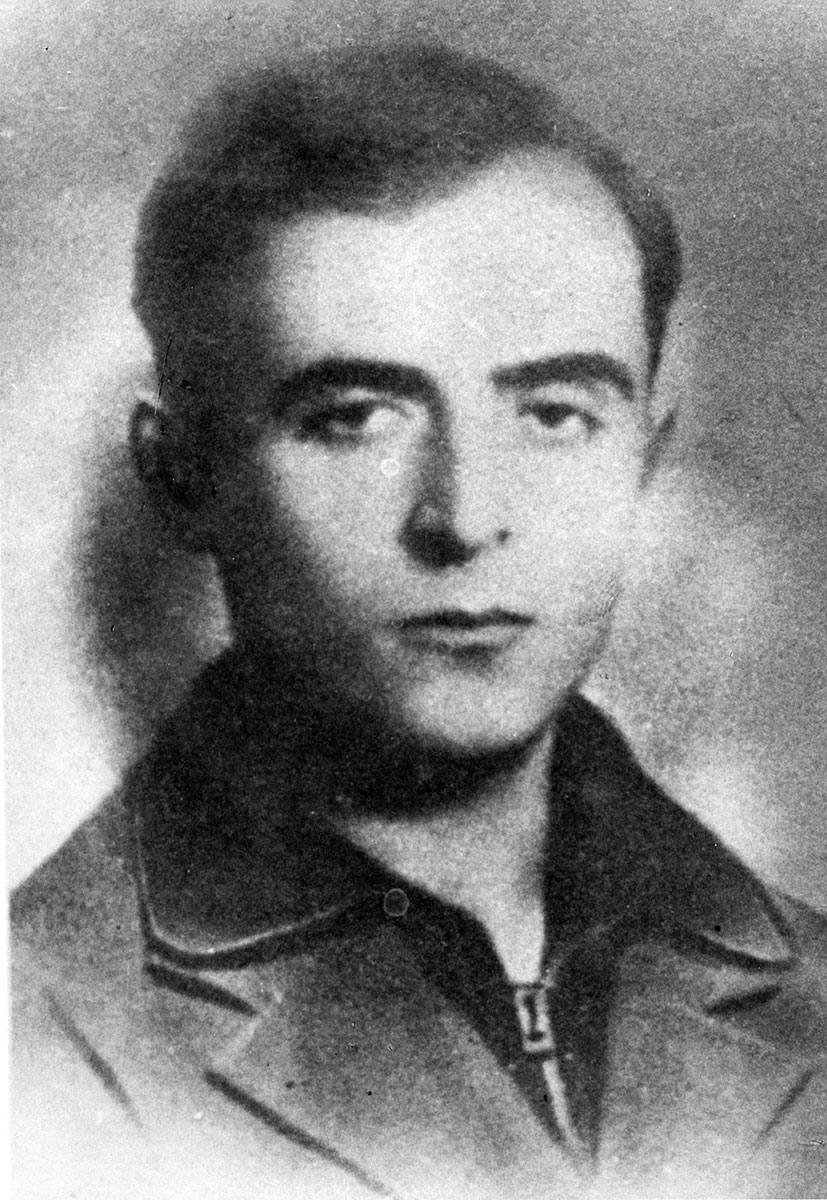

Once in Bialystok, the plan was for the youth movements to coordinate to form a Jewish combat organization, but friction and conflicts among the various ideologies prevented this from happening. Tenenbaum arrived in the Bialystok ghetto on November 1, 1942 from Warsaw. Having witnessed the organization of an underground in Warsaw, he was enthusiastic to set up a united fighting force in Bialystok. However, there were many who were opposed, preferring to flee to the forests and fight the Germans together with the partisans.

A special relationship grew up between Barasz and Tenenbaum. Each kept the other apprised of developments throughout 1942 and most of 1943. Barasz, for his part, understood the desire of the youth movements to resist the Germans. Though he was wary that they could upset the balance in the ghetto and cause a disaster, he even assisted them in obtaining arms and ammunition. He also revealed relevant information he received from his German superiors to Tenenbaum. He believed the ghetto would survive, and wanted to keep an eye on the underground resistance. Tenenbaum, for his part, cooperated with Barasz, informing him as to the development of the coordinated resistance. Several of the meetings Tenenbaum held to plan the establishment of the underground were even held in Barasz's office.22

In light of Barasz's popularity in the ghetto, and the seeming correctness of his assumptions as to the Germans' intentions, the underground in Bialystok never tried to establish itself as an authority to replace Barasz or the Judenrat. Later on, this would greatly impact the final act of uprising.

Finally, at the beginning of February, 1943, the axe fell: the Germans surrounded the ghetto and ordered the Jewish police to round up the Jews. The Jewish police refused, another stark difference between Bialystok and Warsaw. However, though the Germans had to do their own dirty work, over the course of one week, 10,000 Jews were rounded up and taken from the ghetto, and an additional 900 were shot inside the ghetto The Jews of Bialystok who were captured were sent to Treblinka and to Auschwitz.

The underground had decided – significantly, with the input of the Judenrat – to refrain from military action unless it was clear that the Germans intended to liquidate the entire ghetto. The reasoning was that they needed to play for time, since they were short of weapons, had no comprehensive strategy, and the groups were still fighting among themselves. Barasz did not indicate that the liquidation of the ghetto was imminent, and therefore the underground did not react at all to the aktion. Paradoxically, however, this decision not to resist in February of 1943 undermined the underground's standing with the community, while it strengthened Barasz's position.23 Testimony found in the Bialystok archive24 by one of the ghetto residents indicates disappointment:

The question everyone is asking is, Where are the rebels? Where are those who were supposed to launch an uprising against the Germans? We feel despair mixed with bitterness and shame…and a strong sense of disillusionment with the fighters who are out to save their own skins. Is this how they defend our honor and our lives? 25

The underground became divided – while some members, including Tenenbaum, wanted to fight to the bitter end, others – notably the Communists and HaShomer HaTzair – began more seriously considering escaping to the forest to join the partisans. This, too, was an element that would greatly affect the nature of the final uprising, when it came. The members of the underground were faced with a "choiceless choice" – a real, insoluble dilemma: was it better to resist and perhaps die trying, or to try to join the partisans and perhaps live to bear witness? The following is an illustrative dialogue from a stormy meeting held on February 27, 1943, after the aktion, between Mordecai Tenenbaum and other youth movement leaders in the Bialystok ghetto:

Mordecai [Tenenbaum-Tamaroff]: It’s a good thing that at least the mood is good. Unfortunately, the meeting won't be very cheerful. This meeting may be historic, if you like, tragic if you like, but certainly sad. That you people sitting here are the last halutzim26 in Poland; around us are the dead. You know what happened in Warsaw, not one survived, and it was the same in Bendin and in Czestochowa27, and probably everywhere else. We are the last. It is not a particularly pleasant feeling to be the last: it involves a special responsibility.

We must decide today what to do tomorrow. There is no sense in sitting together in a warm atmosphere of memories! Nor in waiting together, collectively, for death. Then what shall we do? We have two options – to decide that when the first Jew is dispatched from Bialystok we will initiate a counteraction: that from tomorrow no one goes to the factory; that when the aktion takes place, none of us is allowed to hide. Everyone mobilizes for action. We must see to it that not one of the Germans gets out of the ghetto alive. That not a single factory remains intact – and it is not impossible that after carrying out this action we will remain alive by some chance. However – fight to the last man, to the end. This is the first option. The second option is to go out to the forest […]Yitzhak [Engelman]: We have to choose one of the two options that lead to death: the first option is to stand up like fighters, and that’s certain death. The second option also entails death, except that death will come only two or three days later. Both options must be examined. We may decide upon some action […]

Herschel [Rosental]: Here in Bialystok we are fated to live out the last act of this blood-stained tragedy. What can we do and what should we do? The way I see it the situation really is that the great majority in the ghetto and of our group are sentenced to die. Our fate is sealed. We have never looked on the forest as a place in which to hide, we have looked on it as a base for battle and vengeance. But the tens of young people who are going into the forests now do not seek a battlefield there, most of them will lead beggars' lives there and most likely will find a beggar's death. In our present situation our fate will be the same, beggars all. […] There is only one thing left for us, therefore, and it is: organizing a collective act of resistance in the ghetto at any cost, to consider the ghetto to be our “Musa Dagh”28 and to add a chapter of honor to Jewish Bialystok and to our movement.

Sarah [Kopinski]: Comrades! If it is a question of honor, we have already long since lost it. In most of the Jewish communities the Aktionen were carried out smoothly without a counter-Aktion. It is more important to stay alive than to kill five Germans. In a counter-Aktion we will without doubt all be killed. In the forest, on the other hand, perhaps 40 or 50% of our people may be saved. That will be our honor and that will be our history. We are still needed, we will yet be of use. As we no longer have honor in any case, let it be our task to remain alive….

Chaim [Rudner]: There are no Jews left, only a few remnants have remained. There is no Movement left, only a remnant. There is no sense speaking about honor. Everyone must save himself as best he can. It does not matter how they will judge us. We must hide, go to the forest....29

Life in the ghetto returned to normal after the February aktion. The factories continued to assist the German war effort. Importantly, the ghetto population was more convinced than ever that the worst was over and the workers would be safe from harm, especially since the Germans had kept their promise not to deport the workers and their families who had hidden in the factories.

The factions of the underground finally unified during the summer of 1943, after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. But Tenenbaum still required Barasz's cooperation. This was when the two parted ways. Barasz, like other heads of Judenraete in many of the other ghettos, was deceived by the Germans. They had promised him that the ghetto, a working ghetto, was essential to the war effort. Even in the February aktion they had promised not to harm the workers and their families, and they had not disturbed those who hid in the factories. The fact that all the other ghettos in the area had been wiped out and their Jews murdered seemed to Barasz to support his viewpoint rather than detract from it: the Germans decisions were logical, and were based on preserving their workforce. Barasz therefore remained unconvinced that the ghetto would be liquidated. The disagreement between Barasz and Tenenbaum, who wanted to mine the area of the ghetto, soured, and then ruptured, their relationship.

In July, 1943, rumors spread through the ghetto that the Germans planned to destroy the ghetto in Bialystok. The Judenrat denied all the rumors, reassuring the ghetto population that nothing was amiss; large, urgent orders had been placed with ghetto factories, and that was the best indicator that the ghetto could not be destroyed. However, on the evening of August 15, 1943, Barasz was summoned by the Germans to Gestapo headquarters, and was told that the following morning, the workers of Bialystok and their families would be transported to work in Lublin. Barasz was stunned. For whatever reason – the rupture between himself and Tenenbaum, the fear that panic would break out, or his shock at hearing of the ghetto's impending liquidation – Barasz failed to inform Tenenbaum of the coming aktion.

At 2:00 AM on August 16, 1943, underground's lookout noticed that the ghetto was being encircled by soldiers with submachine guns, armored vehicles and cavalry. The fighters convened a meeting; there were almost 200 of them. They had about 25 rifles, several guns, a few submachine guns, one heavy machine gun, and several dozen grenades.30 The guns were in poor condition and the grenades were unreliable. The underground's plan of action had to be modified because they were taken by surprise. They had no time to plan an effective counterstrike. The emergency plan they feverishly worked out was based on the assumption that at least some of the ghetto residents would join in the resistance. Women members of the underground were to post leaflets calling on fellow Jews not to surrender. The fighters were sure that Tenenbaum's rhetoric would work.

However, on the morning of August 16, 1943, thousands of Jews obediently did exactly as they were told by the Germans. Barasz was the first to assemble, with his suitcase and backpack.

When the underground saw they did not have the support of the masses, they abandoned their plan of face-to-face confrontation with the Germans, and launched hand grenades from windows and balconies of houses near the ghetto fence. The battles ended when the fighters' ammunition ran out. By the end of the first day, the underground had lost many of its 200 members. Approximately seventy-two fighters had taken refuge in a bunker located underneath the Dror "kibbutz" in Bialystok, but they were found, dragged out, lined up and shot to death. Other fighters were killed trying to break out of the ghetto and reach the forests. It is believed that Mordecai Tenenbaum, together with Daniel Moszkowicz, his deputy and a Communist, committed suicide.31 As Bronka Vinizka, who was in constant contact with Tenenbaum, wrote, "It seems almost certain that Mordecai, who saw his fate as inextricably bound up with that of the ghetto, decided to put an end to his life."32

Though the Warsaw uprising provided inspiration to the fighters in Bialystok, there were many differences between these two stories of armed resistance. Having confronted the Jews in the Warsaw uprising, the Germans were prepared to deal with the uprising in Bialystok. It was the Jews, not the Germans, who were taken by surprise. In addition, the fighters in Warsaw had had the support of the masses, while in Bialystok, the population went obediently to its death, following their trusted leader, Barasz. For these reasons, the major thrust of the Bialystok ghetto uprising only lasted a number of hours.

Conclusion

It was very difficult, for many reasons, to stage an armed uprising in the ghettos of Europe during the Holocaust, and yet – miraculously – there were armed revolts and operations in Warsaw, Krakow, Bialystok, Bedzin, and Czestochowa, and underground resistance organizations were established in Vilna, Minsk and other places. The focus should not be on which uprisings were more or less successful. Instead, we should examine why and how the Jews rose up at all against the Germans in the face of overwhelming odds and almost certain death. This question was posed to Yitzhak Zuckerman by Gideon Hausner, the prosecutor, during his testimony at the Eichmann trial in Israel.

Q. My last question to you - why did the Warsaw Ghetto revolt, why, in your opinion, as you knew the Jewish realities in Poland and other places, why didn't the others revolt? Why only the Warsaw Ghetto, and was it really only the Warsaw Ghetto?

A. I think that is wrong. And I say this from my experience from the period that I was a commander of fighters. It is an error to think that only the Warsaw Ghetto fought and rebelled. In several places the last of the Jews tried to revolt. I cannot accept the idea that my comrades in Czestochowa, who had less arms, less Jews, less fighters, and they fell upon the Germans with their fingernails and fought until the last moment - I cannot accept the idea that they did not fight. I am convinced that they put into this struggle of theirs not less than we in Warsaw, even though they did not achieve the same effect.

Q. And what happened in Bialystok?

A. In Bialystok, too, there was an organized revolt, if I am not mistaken, on 16 August 1943. In Bedzin there was an uprising of Jews, of members of the Jewish fighting force, in the bunkers; in Cracow there was the revolt of the Jewish youth, and the same thing in many other places.

Q. And what about the extermination camps themselves?

A. This is a chapter which, with all its great horror, contained a ray of light, although this was already at the very end. If the last of the Jews, who were there, still had the strength, in Treblinka, in Sobibor, and in Janoska, to carry out underground activity in Hazag, in Peltzri, in Skarzysko, and Radom, in the camp at Piotrkow...

Q. And in Auschwitz?

A. In Auschwitz the Jewish underground was integrated with the general underground. But the very fact that this was possible in Treblinka after the murder of 750,000 Jews, and possibly more than that - in my estimation - the very fact that the last of the Jews were able to revolt, points to the fact that they gave proof of unusual heroism.

Q. This was a reply to my second question; namely that not only the Warsaw Ghetto revolted. But why, in the Warsaw Ghetto, were they capable of the action that took place?

A. I think that the conditions for fighting - and if we are talking of a revolt in the ghettos, it began in Warsaw - well on the eastern border area, which was much nearer to the swamps and the forests, there was a large movement of Jewish partisans, at least 20,000 Jewish youth fought in Byelorussia, in Lituania and in Ukraine. Then it was not only that we were different, the form of fighting was different.

It is true that the Jewish fighting force had a point of view of principle in this matter. It wanted - not only because the forest was far away and it was impossible to get there, it wasn't possible to get near the forest - it was an ideological approach to fight in the ghetto. For we couldn't allow ourselves, we the younger ones, the braver ones, to abandon the masses of the people, the elderly persons, our sick, to leave them in the ghetto so that they could be taken to Treblinka. Therefore we deliberately chose to revolt. And not only in Warsaw.

This was the reason for my journey to Cracow…in order to rescue what could be saved. If not life itself - at least our honour….33

Zivia Lubetkin summed up the motivation of the fighters, who understood from the beginning that resistance was futile and yet chose to fight anyway:

Q. When you began the revolt, you knew what the end would be. Did you have any chance to defeat the German army in battle?

A. There was no chance of defeating them in battle. That was clear. This was still in April 1943. The victories of the Red Army were only beginning. And it was plain to us that we had no chance of winning in the accepted sense of the term.

Q. In the military sense?

A. Not in the military sense or in the accepted sense of today. But, believe me, and this is no empty phrase, that despite their power, we knew that ultimately we would defeat them, we, the weak ones, because in this lay our strength. We believed in justice, in humanity, and in a regime different from the one which they glorified.34

- 1.Sara Bender, "Resistance in the Bialystok Ghetto", in Daniel Grinberg, ed., The Holocaust Fifty Years After (Warsaw: The Jewish Historical Institute of Warsaw, 1993), p. 171.

- 2.In the Generalgouvernement, the Star of David was a blue star on a white background worn on outer clothing. Elsewhere it was the familiar yellow star.

- 3.An aktion is a round-up of the Jews during a deportation.

- 6.For an article on the couriers, the brave – mostly female – members of the youth movements who traveled from ghetto to ghetto with news, boosted morale and sometimes smuggled in arms and weapons, see a previous issue of this newsletter.

- 7.Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, Eli Pfefferkorn, David H. Hirsch, eds., Roslyn Hirsch, David H. Hirsch, trans. (Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), pp. 24-26.

- 8.Hachshara involved training, including agricultural and ideological training, for purposes of immigration to Israel.

- 9.Yael Peled, Jewish Krakow 1939-1943, Her Stand, Underground, Struggle (Upper Galil: Ghetto Fighter's House, 1993), p. 132 [Hebrew].

- 10.Dr. Felicia Karai, Heroism Has Many Faces (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2002), p. 65 [Hebrew].

- 11.Yael Margolin Peled, Jewish Women's Archive, Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, accessed November 11, 2012.

- 12.Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, p. 24.

- 13.Yitzchak Zuckerman related, at the Eichmann trial, that "after the Jews of Cracow had been done to death, there remained a small, reduced ghetto. The Jewish underground was known there; as in the case of every group, there was a collaborator, an informer or traitor, who informed on the heads of the underground movement and these members had no alternative but to leave the ghetto and set up bases on the Aryan side of Cracow. See also another article in this newsletter dealing with the dilemmas of revolt.

- 14.Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, p. 25.

- 15.Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, pp. 2-3.

- 16.Friday evening marks the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath. Traditionally, Jewish families share a meal together to celebrate the Sabbath.

- 17.Yehuda ("Poldek") Maimon, a member of HeHalutz HaLochem in Krakow, is the source for this statement. Poldek has testified many times that at the Last Supper Dolek stated that the youth were "fighting for three lines in history." Poldek's testimony to this effect can be seen in the testimony film made for the Yad Vashem museum: The Krakow Ghetto. Film. Directed by Noemi Schory, Belfilms. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2005. The statement also appears in Dana Weiler-Polak, "Little Left to Lose," HaAretz, May 2, 2011, accessed August, 2013.

- 18.Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, p. 6, n. 6 sets the figure at 7; the US Holocaust Museum sets the figure at 12.

- 19.See the discussion in the Editor's Note to Justyna's Narrative, which contains a story told by Hela Rufeisen-Schipper, one of the couriers of the underground. Traveling by train soon after the attacks, she was told by a Pole she was traveling with that the war would soon be over because Polish forces had begun to move. "Take my word for it, they are already carrying out acts of sabotage, like blowing up railroad tracks, and I read in the underground paper that in Krakow, too, our boys, the Polish underground, have attacked German cafes with grenades and bombs, inuring and killing many Germans. How proud they make me!" Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, p. 6, n. 6.

- 20.The formally-appointed head of the Judenrat in Bialystok was city’s chief rabbi, Dr. Gedaliah Rosenmann.

- 21.As explained in a different article in this newsletter, where the text of Kovner's proclamation appears, the Judenrat leadership, appointed by the Germans to do their bidding, tried to find logic behind the Germans' orders until the very end. This leadership was convinced that the Germans would not murder all the Jews because they constituted an important element of the workforce. As such, the Judenrat in various places refused to come to the conclusions that the youth movements came to, and never awoke to the realization that there was a plan to murder all the Jews of Europe.

- 22.Sara Bender, "Resistance in the Bialystok Ghetto", in Daniel Grinberg, ed., The Holocaust Fifty Years After, (Warsaw: The Jewish Historical Institute of Warsaw, 1993), p. 157.

- 23.Bender, p. 183.

- 24.Bender, p. 169.

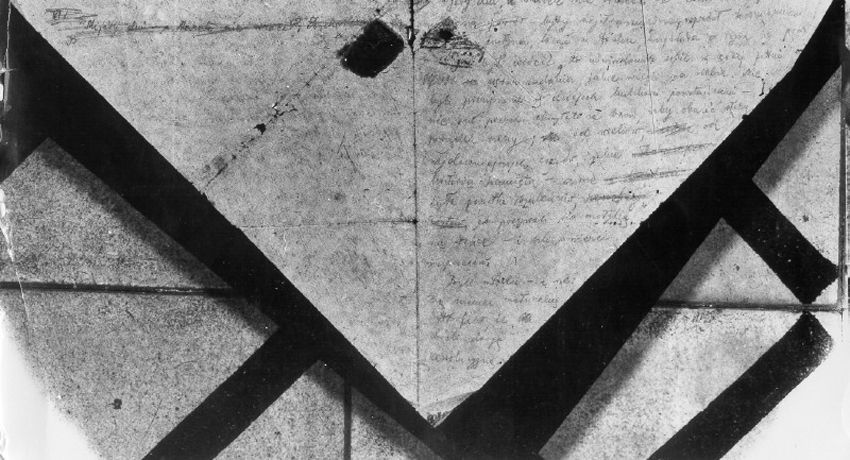

- 25.One of Tenenbaum's most important accomplishments, together with Zvi Mersik, was to collect historical data for inclusion in a secret archive. In doing this, he was inspired by the work of Emanuel Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat archive in Warsaw. Tenenbaum kept a diary and submitted it to the archives together with letters he wrote, and he also encouraged others to write diaries and memoirs. He collected testimonies from refugees who wound up in the Bialystok ghetto. Barasz supported the archive and gave Tenenbaum documents and photos, Judenrat notices and minutes, and also personal items found in the clothing of dead Jews sent to Bialystok from Treblinka for cleaning and sorting. Like the archive in Warsaw, the Bialystok archive was hidden; in Bialystok, special hermetically-sealed metal containers manufactured by the ghetto locksmiths were used. These were delivered by a courier named Bronka Vinizka to a local Pole, who hid them in a shed in his courtyard. Most of the archive was found after the war.

- 26.Bender, p. 208.

- 27."Halutzim" is the Hebrew word for pioneers.

- 28.This estimate is the result of lack of information on what happened in Warsaw. In the deportation that took place in Warsaw in January, the Jewish Fighting Organization lost only part of its people. The information on Bendin and Czestochowa is also based on incomplete knowledge of the situation.

- 29.This is a reference to the book “The Forty Days of Musa Dagh” which tells of the Armenian genocide by the Turks during World War I, written by the Czech-Jewish novelist Franz Werfel.

- 30.Arieh Carmon, Yair Oron, eds., Jewish Vitality in the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Ministry of Education, 1975), p. 59.

- 31.Bender, p. 254.

- 32.Bender, pp. 268-269.

- 33.Ibid.

- 34.Eichmann trial testimony