Overall, the vast majority of SS and various other personnel who had served at the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex were never brought to justice. Only sixty-three of the approximately 7,000 SS personnel who served at Auschwitz, including Birkenau, Buna-Monowitz, and satellite camps were tried after the war. The first Auschwitz trial took place in Cracow, Poland, in November and December of 1947. Forty-one SS personnel were tried by the Polish authorities. The second trial of twenty-two SS officers took place in Frankfurt, Germany, between December, 1963 and August, 1965.

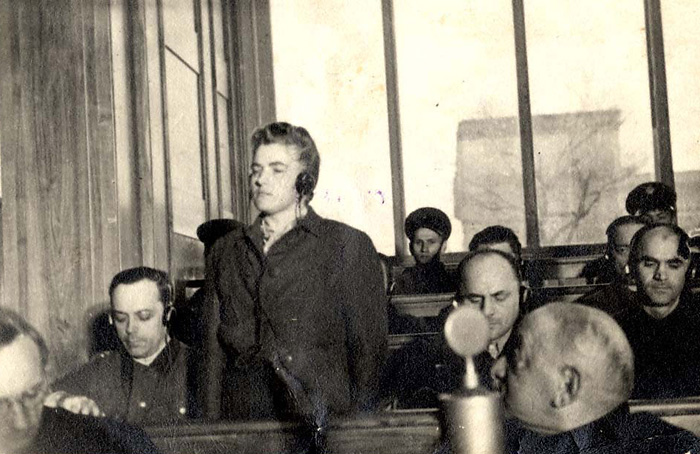

First Auschwitz Trial: November 24, 1947 - December 22, 1947

The Polish authorities tried forty-one senior SS personnel (thirty-six men, five women) who had served at Auschwitz. The top echelon of the camp hierarchy were put on trial, including: Rudolf Hoess, Arthur Liebehenschel, camp commanders; Maria Mandel, who controlled the women’s camp; Johann Kremer, a high-ranking physician in the camp, and others. The most senior of the defendants, headed by Rudolf Hoess, testified on behalf of the prosecution as part of the Nuremberg Trials.

Most of the defendants had been handed over to the Polish authorities by the Allied forces. This trial, which lasted only one month, included survivor testimony, and the judges perused a wide variety of German documents. Twenty-four of the defendants were sentenced to death, including Rudolf Hoess, Arthur Liebehenschel and Maria Mandel; of the others, three received life imprisonment, seven received fifteen years in prison, and one was acquitted.

On April 16, 1947, Rudolf Hoess was executed in front of Gas Chamber #1 in Auschwitz I. The rest of the defendants who had received the verdict of capital punishment were executed in Cracow Prison on January 18, 1948. Maria Mandel was the first to be executed.

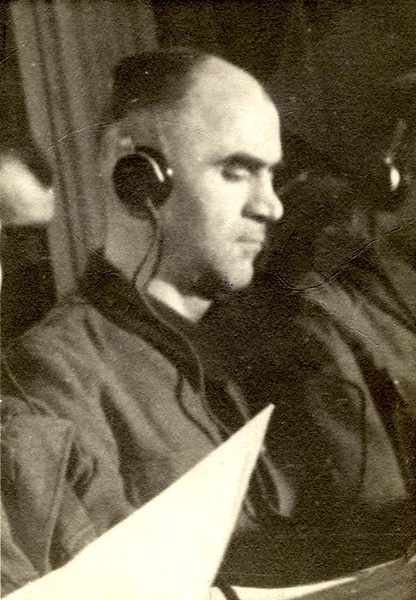

Second Auschwitz Trial: December 20, 1963 - August 10, 1965

In this series of trials, twenty-two Auschwitz personnel – second and third tier officers and capos – were tried. Unlike the first trial in Cracow, based on international law and the legal definition of crimes against humanity, these trials were conducted according to German criminal law.

Over the course of the trials, some 360 witnesses were summoned, including approximately 210 camp survivors. Fritz Bauer – then Germany’s Attorney General and himself a former prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp in 1933 – headed the prosecution. News of the criminals’ actions and whereabouts had been known in West Germany from 1958, but they had not been brought to justice due to legal issues. Moreover, despite de-Nazification measures enforced by the Allies in Germany, many former SS and Nazi Party members maintained high-ranking governmental positions. Eighteen of the accused were found guilty. Six of the eighteen were sentenced to life in prison and the others received sentences ranging from 5-14 years. Many of the accused never served their full sentence.

The trial proceedings were open to the public, and helped bring further information about the Holocaust to the citizens of West Germany and around the world.

The Auschwitz Trials in Historical Perspective

How can we explain the difference between the first and the second Auschwitz trials? How do we explain the disparity between the sentences? Why was such a small number of Auschwitz personnel brought to trial?

The difference in severity of the sentences handed down cannot be explained by the higher ranks tried in the first trial and the lower ranks of SS personnel in the second trial as they were all murderers – irrespective of rank. The disparity was a result of the legal systems. The first Auschwitz trial was held according to the laws against war criminals and crimes against humanity, the legal code that was established in the Nuremberg Trials. The second trial was held within the framework of German criminal law, making it more difficult to convict some of the accused.

As mentioned earlier, de-Nazification in Germany was not implemented in all high government levels including the Justice Department. This situation led to the "dissappearance" of many of the criminals. Second, Fritz Bauer, the prosecutor in the trial, who was also the chief prosecutor for Federal Germany and responsible for finding, interrogating, and bringing these criminals to trial, invested great efforts in uncovering documents and testimonies relating to the system and structure of the camps, and far less in bringing specific persons to trial. As a result of these factors, most of the criminals remained outside of the second Auschwitz courtroom, which was supposed to have been the main trial for all Auschwitz personnel.