- The exhibition Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery/Recent Art that was held at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2002 gives us a good impression of shocking contemporary art. For discussions concerning the exhibition see: Rohr, Susanne. “Genocide Pop”: The Holocaust as Media Event. In: Komor/Rohr: The Holocaust, Art, and Taboo. P. 155-178. Heidelberg, 2010.

- Biber, Katherine, Bad Holocaust Art. In: Law Text Culture, 13(1), 2009, p. 228.

- Ibid. p. 241.

Artistic representation of the Holocaust has become a matter of some controversy. The controversy focuses around questions such as: Can art represent the Holocaust? And if so, in what way should it be represented? Can it give us a picture or an image of the Holocaust? Can art teach us anything about the Holocaust? Should there be limitations to the artistic representation of the Holocaust? Where should the boundaries be? Who should decide these boundaries?

This article discusses two of the controversies:

- The limits of art as proof or testimony.

- The moral limits of artistic representation.

The limits of art as testimony

Regarding the first controversy, it has been argued that art, especially a painting, is not to be seen as an equal to a historical document, and thus serves less as proof of the “reality” of the Holocaust. Art is usually seen as something subjective, while academic products such as articles, books, and written testimonies are looked upon as “neutral,” historically correct, and as representing the “truth.” For instance, if researchers read the name of a Nazi in a testimony it is easier for them to take action to identify him and corroborate the witness’s testimony as opposed to a situation where they come across a face of a Nazi in a painting. Does this mean that a visual memory is less valid than a name one has heard?

This is a central reason why educators often approach the Holocaust through the use of academic articles and written testimonies. But this is not the only way of deepening one’s knowledge and understanding. Artistic representations offer a valuable insight into understanding this complex subject.

First, the Holocaust, like any other historical event, is presented to us by a summary of accounts from different mediums – documents, photographs, diaries, letters, and visual art. All these different accounts show us reality, but they can only show us one excerpt of “the reality,” one picture or part of the whole. And the specific parts mediated to us through the different accounts strengthen different aspects and limit others due to their own nature. While an academic article can speak to us on a rational level and explain the circumstances of an event, a painting can engage us in a more direct fashion, and share with the observer the artist’s feelings, thoughts, or memories through his or her expression.

Second, all the types of testimonies mentioned above, are conveyed by individuals. Thus any account created by a human – whether it be an academic article or a painting – is always entirely subjective because it was created by an individual; that is, any such account presents us with the perspective of the creator of the account alone. Naturally, two different people might have experienced the exact same situation in a totally different light: whereas one Holocaust survivor of a concentration camp might present a specific event as a living hell, another artist might focus on the humanity among the inmates during the same event.

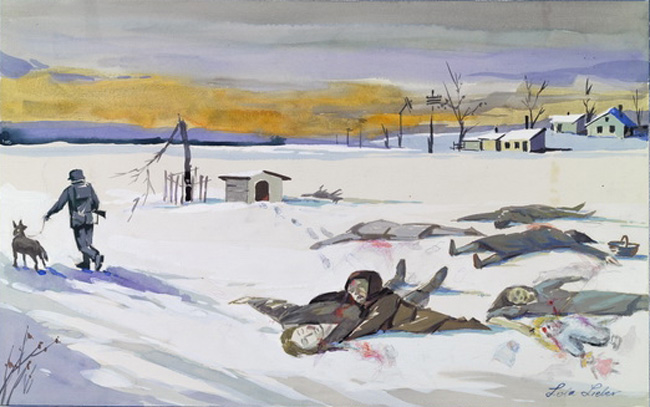

The painting of Lola Lieber-Schwarz - The Murder of Matilda Lieber, Her Daughters Lola and Berta, and Berta’s Children Itche (Yitzhak) and Marilka, January 1942 is an example of a very detailed and realistic painting that acts as a witness and a testimony to a horrible murder. It depicts a scene of a family lying dead on the snowy ground outside a village. We are exposed to the perpetrator – the Nazi – and his dog walking away from the scene. We do not see his face, only the back of his head. The scene feels very cold and dead, with only the perpetrator and maybe one of his victims, a child clinging to its mother, still remaining alive. In this event there seems not to have been anyone present to take a photograph and to testify about what happened. We do not know who the witness of the scene is, whether she is one of the people being shot or whether the scene was witnessed from afar. And we also don’t know the relationship of the artist to the people depicted.

While this painting is realistic and almost seems like a photograph, the painting of Ilana Ben-Israel – Green Poland and its Buried Treasures, is a mixture of abstract and realistic proof. We can see a beautiful green landscape and within it the horrifying impact of a murder. There are ghostly and almost invisible people standing on the edge of a killing pit. Only one girl is painted in color and dressed as a living person, thus giving the impression that she is the only survivor of a mass shooting and may even be the artist herself. The title is highly critical and sarcastic. Both paintings represent a mass murder but in very different ways. While Lola Lieber-Schwarz realistically depicts the dead family lying on the ground covered in blood, Ilana Ben-Israel’s work does not stick to the limitations of “reality” and creates ghost-like figures that challenge the observer’s mind. In both, the perpetrators are not present in the scenes. We neither see the actual murder nor do we see the realistic evidence in the form of corpses. But we do see the imagination and expression of the artist and can imagine her feelings about what happened, which is also evident in the name she has chosen for this painting.

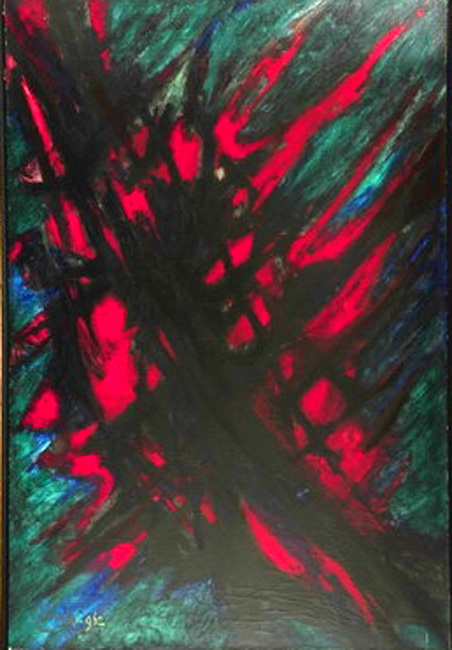

Without historical contextualization some images can become nothing more than an empty sign that can be filled with anyone’s own interpretation, as can be demonstrated in Haim Bargal’s The partisans' river. This is a very powerful oil abstract with strong colors. The work recalls a battle over a river crossing between resistance fighters and the German army. The water was colored red with the blood of the people fighting, according to the artist.

Without an explanation we have no way of knowing what is depicted in this painting. If we saw this out of context in a museum or private house, we may not guess that it had anything to do with the Holocaust. But with some context or even just a title, we can see and feel a lot in it.

Though these three examples of artistic expressions and styles are very different in presenting the Holocaust, each painting is an important testimony: as parts of a whole picture, of one reality, of the many realities that is the Holocaust. The Holocaust is a collective history, but at the same time it is a personal and individual one as well.

Art can be a wonderful tool in understanding the Holocaust. Therefore art needs to be seen as it is, with its advantages and limitations. Conveying realities that survivors went through to people that did not experience these things can be a difficult task. Furthermore, creating art is a very personal vehicle to express one’s inner self. Sometimes art is the only way of dealing with memories and expressing one’s feelings. It is an individual act of expressing what happened and therefore it has to be seen as such. It cannot present the entire Holocaust, but can present one perspective on the Holocaust by means of one image.

Any representation of the Holocaust – be it a painting, a sculpture, a poem or a novel – can never adequately convey the reality of the actual experience. It does not necessarily communicate an unambiguous message. Some artists present their art piece as reconstruction of the truth, others as mere expression of feelings that have no further message or function to the outside world. And even if there was only one message, there are still the observers that have their own interpretations of what the artist’s message might have been. How the art piece is read and interpreted is beyond the artist’s control. An artwork can teach us what happened, what people felt, how they saw different events, what their message is to us, and it can also teach us about absence. But our conclusions as observers might be very different to one another. To form a picture of the Holocaust we need different historical accounts that mesh together to form a bigger picture. But this picture as well will always remain incomplete.

Is it morally correct to attempt artistic representation at all?

This leads us to the second controversy: if no form of representation is able to fully convey the whole reality of the Holocaust and the pain and suffering experienced by the Holocaust survivors, is it morally correct to attempt representation at all? Is this a crime scene that should not be represented? In what way should the Holocaust be remembered? Are there moral or aesthetical boundaries of artistic expression? And who, if anyone, should make those decisions?

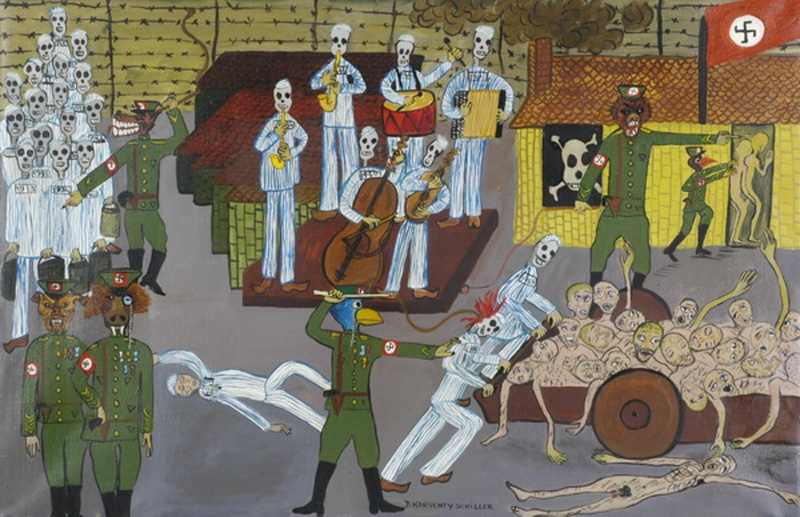

The artist Daniele Karsenty-Schiller visualizes a concentration camp in her painting A la gloire Nazi. The painting almost feels like a scene from a circus. Nothings seems real, everything seems surreal. The Nazis are depicted as animals with faces such as wolves, bears, and birds, and the inmates are painted as skeletons wearing striped pajamas while playing in an orchestra or working. The inmates are painted as if dead, without any human expression on their skeletal faces. They are only inhuman corpses playing in a big play. Only after their deaths do they regain their humanness and individual bodies and flesh.

This painting is a testimony and a proof of the horrors of the concentration camp. At the same time it is abstract and surreal and it depicts what no photograph can depict. It shows us the artist’s interpretation of the experience and her emotions. Nazis sometimes referred to their victims as Figuren – simply figures, dolls or pieces in a chess game – thus inhuman. The artist illustrates this process of the Figuren as part of the dehumanization process of the Nazis‘ death machinery in a shocking and absurd way.

In some cases an art piece has the ability to affect the viewer more deeply than words can. While words structure our understanding of the world, visual art is immediate and emotional. Even glancing at a terrifying art piece can be a shocking confrontation that is immediate.

While some artists depicting the Holocaust test whether it is possible to employ irony and satire, it is important to point out that not every artist might have the intention of shocking his or her audience. Some artists merely want to testify to what they saw and experienced or express their feelings. Some want their audience to witness and some want the viewer to respond.

Shocking Art

There are artistic representations of the Holocaust that can be deeply offensive or merely shocking1. Should they be forbidden? Can they teach us anything? Or do they just offend, shock and leave us speechless?

One line of critical thought argues that there ought to be strict boundaries imposed upon what can be said and created about the Holocaust. Others argue that art is supposed to break limits and reformulate, and therefore it needs to have complete freedom. They also point out that art cannot do bad or evil things and raise the question: what can be more shocking than the actual thing? Even though art cannot act on its own, it is definitively able to create a painful experience for the viewer and to hurt one’s feelings. Art does not exist in a vacuum; someone always creates it or performs it, and someone always responds to it.

These discussions demonstrate that there are two major concerns. One addresses the survivors and their privacy and dignity that need to be respected, and argues that we are given a moral responsibility to observe certain boundaries when we seek to present atrocities.

“At the center of all Holocaust discourse is the duty to be responsible; responsibility is the hard kernel at the heart of every Holocaust representation."2

A lack of sensitivity can hurt the feelings of those who suffered the atrocities.

The difficulty lies in locating the boundaries of the presentable. Many people argue that survivors themselves should decide where the limits are. But in making this supposition we forget that although linked by collective memory, each survivor of the Holocaust is an individual and has his or her own idea of what is or is not appropriate. It also depends on who the artists are. What might be seen to be an appropriate work of art if done by a Holocaust survivor might seem to be inappropriate if created by an artist who has nothing to do with the Holocaust and seems to only be seeking an artistic career.

The other concern deals with the observers of shocking art. Some people presume that the audience “needs to be shocked into remembrance [and that new] horrors need to be introduced to remind us that Holocaust crimes remain horrifying.”3 This argument feels strange to me since it leads to the assumption that once we see a shocking picture we get used to it and adopt it to our worldview. As we become numb and number we need more and more shocking, violent and horrifying images? I don’t believe that this is the case. One and the same image can be shocking and terrifying each time we look at it, and it does not lose its effect. Moreover, each individual is different and reacts differently to images.

While certain aesthetical practices may be inappropriate, we need to exercise caution before claiming that inappropriate practices are unacceptable and should be forbidden. We should ask ourselves if we want to limit people’s rights to express themselves and share their ideas, and if there are things that should rather not be seen or spoken about. This discussion is reminiscent of how such things could have happened in the first place partly by prohibiting freedom of speech and artistic expression, and how hard it was for some survivors to express their experiences.

The use of shocking art may have some advantages as it catches the viewer’s attention. Once the viewer’s attention has been caught, it can serve as a doorway to learning and thinking about the atrocities of the Holocaust. But it is important to be aware of the negative psychological effects as well. A shock can block people and close them up, therefore disabling them from learning anything.

It is not that the conversations about boundaries cannot take place. On the contrary, there should be discussions. But the artist’s background and his intentions must be analyzed carefully.

Lessons of Holocaust art

It is also not correct that the Holocaust can teach us only about atrocity, terror and cruelty. On the contrary, it can tell us a lot about emotions, human interactions like friendships, mutual support, resistance and bravery. This can be seen, for instance, in portraits that were painted by artists in the camps for other inmates. Often, portraits were painted in order not to forget what people looked like, to testify, to remember, or to simply give to another inmate as a present.

It is important to show survivors’ art, especially since the Nazis wanted to kill not only the Jewish people but also every memory of them. So, any picture and depiction of the reality is important for our memory and our commemoration of the past. Some art is not only about the Holocaust as a crime scene. It is also about the last Jewish generation in Europe and about loss – loss of a culture, family, and a people.

Conclusion

As discussed above, one of the problems concerning visual art is that people question its truth. Many people argue that academic written accounts are more valid than the world of visual arts. as we've seen, however, the two are not mutually exclusive. One can make a deliberate choice to use a painting for deepening the understanding and empathy of the observer. This is especially true since part of understanding the Holocaust is also an understanding of what the atrocities did to individuals on an emotional level.

The memory of the Holocaust has been invaluably enriched by artists providing us with a window to an event that for many people is very difficult to comprehend. The use of visual art can be an excellent educational resource in creating a more immediate and vivid understanding of the Holocaust as well as a personal inside view, in contrast to more distant academic view. The works of art provide valuable information on the life of survivors. They are historical documents that bear witness to the Holocaust.

As every historical account has its limits - so does an art piece. Its representation is individual and always subjective. But that doesn't make it less valid. Visual art pieces need to be understood as perspective and fragmented moments of an event, not as an image of the whole Holocaust. They are impressions of the reality as well as their own interpretation. Art is a great tool of expression, a visual testimony and proof. Sometimes words alone cannot express what a survivor saw, experienced and feels.

The artist’s intentions and the character of an art piece can differ widely. Some artists merely create art privately for themselves; others create for an audience and make their art public. Art can be very abstract but also very detailed and can serve as evidence (for example in combating Holocaust denial). Some artists have a message and a motif; others don’t.

Educators can explore how the visual, in contrast to the textual, serves the processes of memory. They can explore the place of feelings in visual representations, as well as the appearance of time, space and perspective in the work of art.

Since an artistic representation is exclusively a specific form of dealing with the historical event in which truth and the lack of transparency meet, it cannot entirely speak for itself. For this reason it is important to put it into a context and to connect it to other archives of knowledge and presentation.