- Primo Levi was a Jewish Italian chemist who is best known for his scathing powers of observation, as recorded in the many books, poems and stories he wrote after spending one year in Auschwitz.

- Shelley Hornstein and Florence Jacobowitz, eds., Image and Remembrance: Representation and the Holocaust (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), p. i.

- “Gedo, Ilka,” accessed December 18, 2011.

- “Halina Olomucki Biography,” accessed December, 2011.

- Ibid.

- Charlotte Delbo, Auschwitz and After (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), p. 267.

- 1993 ,עצמון, שרה, מחצר השטן, הכנסת-ירושלים

We are accustomed to reading testimonies of Holocaust survivors, or of hearing survivors speak and tell their stories. However, words, in whatever form they may take, are not the only avenue of commemoration or documentation, and sometimes they are insufficient to express the full range of feelings of a survivor. There are those Holocaust survivors who have chosen instead to use not words, but paper, canvas, clay, and other materials as the medium through which they express themselves. Primo Levi1 wrote:

On many occasions, we survivors of the Nazi concentration camps have come to notice how little use words are in describing our experiences. Their “poor reception” derives from the fact that we now live in a civilization of the image, registered, multiplied, televised, and that the public, particularly the young, is ever less likely to benefit from written information…[I]n all of our accounts, verbal or written, one finds expressions such as “indescribable,” “inexpressible,” “words are not enough,” “one would need a language for…” This was, in fact, our daily thought; language is for the description of daily experience, but here it is another world, here one would need a language “of this other world,” a language born here2.

This observation, made by a survivor of the Holocaust (who, in fact, is best known for his written descriptions of life in Auschwitz), perhaps speaks best for the survivors whose works of art are portrayed here. These people, many of whom are not professional artists, have tried to create a visual conduit to somehow express the inexpressible; a plastic, accessible language to describe the indescribable. This is no easy feat.

Why do survivors create art? Perhaps the question would be better put: why do many survivors feel the undeniable need to create art – for it seems that the art of many survivors is indeed created out of a deep-seated need. This may be a need to memorialize those who did not survive – something more akin to an obligation. It may be a need to confront the burden they carry with them as survivors. But it seems that in any event, for many survivors there is an urge they cannot resist. They use their artwork to tell their individual stories to the world and to illustrate the atrocities they experienced.

This article will examine a particular mode of artistic expression – the use of portraits created by survivors – in order to explore their common themes and the need of the artists to use art for purposes of commemoration. The beauty of art is that there is no single, definite or “correct” interpretation – every viewer can see something different in the same work of art. I present here a model for discussion that can be applied to other survivor artwork, and certain tools in trying to understand what is, after all, a very personal expression by the survivors.

Portraits

A conventional portrait is meant to be a recognizable likeness of a person. Generally, the face, with its particular expression, is predominant in a portrait. In this way, the artist who paints a portrait can capture – by recreating the subject’s face – the mood, the age and the outlook of the subject. Often, indeed, the subject of the portrait is painted so that she seems to look directly at the viewer – this helps to more successfully engage the viewer, and makes the experience of looking at the portrait a much more intimate one.

Self-portraits, especially, are intimate. To understand this, it helps to think about the act of the artist when she creates a self-portrait. She must decide what of her own features to show – how should she express her eyes? Her mouth? What expression should be on her face – should she be smiling? Frowning? Should she be mysterious? How much of her persona, of her psyche, does she want to reveal? What kind of mood should she show herself in, and what does she want to express to the viewer of the self-portrait? Before she creates the self-portrait, the artist must have an internal dialogue with herself – she must decide all these things in order to decide what she wants to show on the canvas.

Portraits and self-portraits would seem to be perhaps the highest and best form - or if not, at least the most natural form – of commemoration in that they actually directly present the person being commemorated. Just as a writer describes a subject in words, by painting or sculpting a recognizable face, an artist pays tribute to a person and evokes that person’s life and memory. A portrait renders its subject almost immortal.

As can be seen below, portraits done by Holocaust survivors range from the conventional to the very unconventional. They explain as much about the survivors’ state of mind when they created their artwork as they do about the subject of the work. Indeed, at times, rather than expressing identity in a recognizable form, they express a jarring loss of identity, the result of the trauma experienced by the artist.

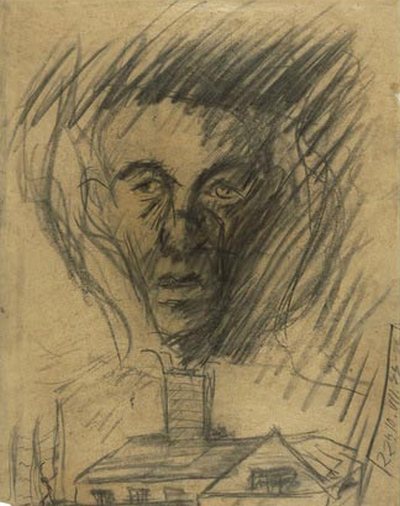

Yehuda Bacon, “In Memory of the Czech Transport to the Gas Chambers”

Yehuda Bacon’s drawing, “In Memory of the Czech Transport to the Gas Chambers,” is in some respects the most conventional of the portraits presented here. In the charcoal drawing, the viewer sees a very specific, idiosyncratic face that is obviously the likeness of someone the artist knew. The face is thin and exhausted, but the eyes are alive and blazing. This is where the realism ends, however. Disembodied and positioned directly above the chimney of a crematorium, the suspended head blends with and becomes a part of the thick black smoke that surrounds it. Below the head, where the body of the subject should be, the artist has drawn not only the crematorium, but barbed wire. An unidentified figure is hanging from the barbed wire fence on the left; presumably someone has committed suicide. On the bottom right, the artist has added a curious notation: 10.VII.44, 22:00, which we can identify as a date – July 10, 1944 at 10 PM.

To understand this drawing fully we must know more about Yehuda Bacon’s Holocaust experiences. Yehuda was born in Czechoslovakia to a Hassidic family. He was deported with his family to the Theresienstadt ghetto when he was thirteen years old, and two years later, on the seventeenth day of December, 1943, Yehuda and his family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was allowed, briefly, to stay with his family in a “family camp” in Birkenau, apparently created by the Nazis as part of their elaborate hoax to deceive the International Red Cross, should they visit the camp. (The Red Cross visited Theresienstadt on June 23, 1944). Czech prisoners from Theresienstadt did not undergo Selektionen, nor were their heads shaved as part of the humiliating absorption process upon arrival at Birkenau. They were not assigned to forced labor details, they were allowed to receive parcels and even to write letters. All of this was exceptional at Birkenau. However, the “show” staged by the Nazis was for a limited time only; the Czech prisoners’ cards all bore the notation "Sonderbehandlung 6 months”. Sonderbehandlung, literally “special treatment”, was the euphemism employed by the Germans as a secret code for execution, generally in the gas chambers. The Czech prisoners didn’t know it, but they were all scheduled to be killed after six months at Birkenau. Yehuda managed to survive because Dr. Mengele performed a Selektion on the boys in the children’s block, and he was taken to work; however, his father was murdered, together with the thousands of Czechs who had arrived in December, 1943, in massive gassings that were carried out between July 10-12, 1944.

With the knowledge of this story we are better able to decipher the portrait: it is Yehuda’s father’s face that is rising from the smoke of the Auschwitz crematorium. The date at the bottom is the exact date and time of his father’s death. Yehuda has conjured up the spirit and the presence of his father from out of the smoke of Auschwitz and has marked the exact moment when his father perished.

This is, then, a portrait of a man being murdered. Although we do not see an actual murder, we see the imagination and expression of Yehuda, and we can imagine his feelings as his father disappears skyward in the smoke of Auschwitz. Yehuda created this portrait when he was sixteen, a short time after his liberation. By illustrating his father’s murder on paper, Yehuda memorialized his father’s death, and ensured that the day would not be forgotten. The portrait is, then, not just commemoration of his father, but also Yehuda’s testimony about the event – as discussed in the article in this newsletter by Franziska Reiniger.

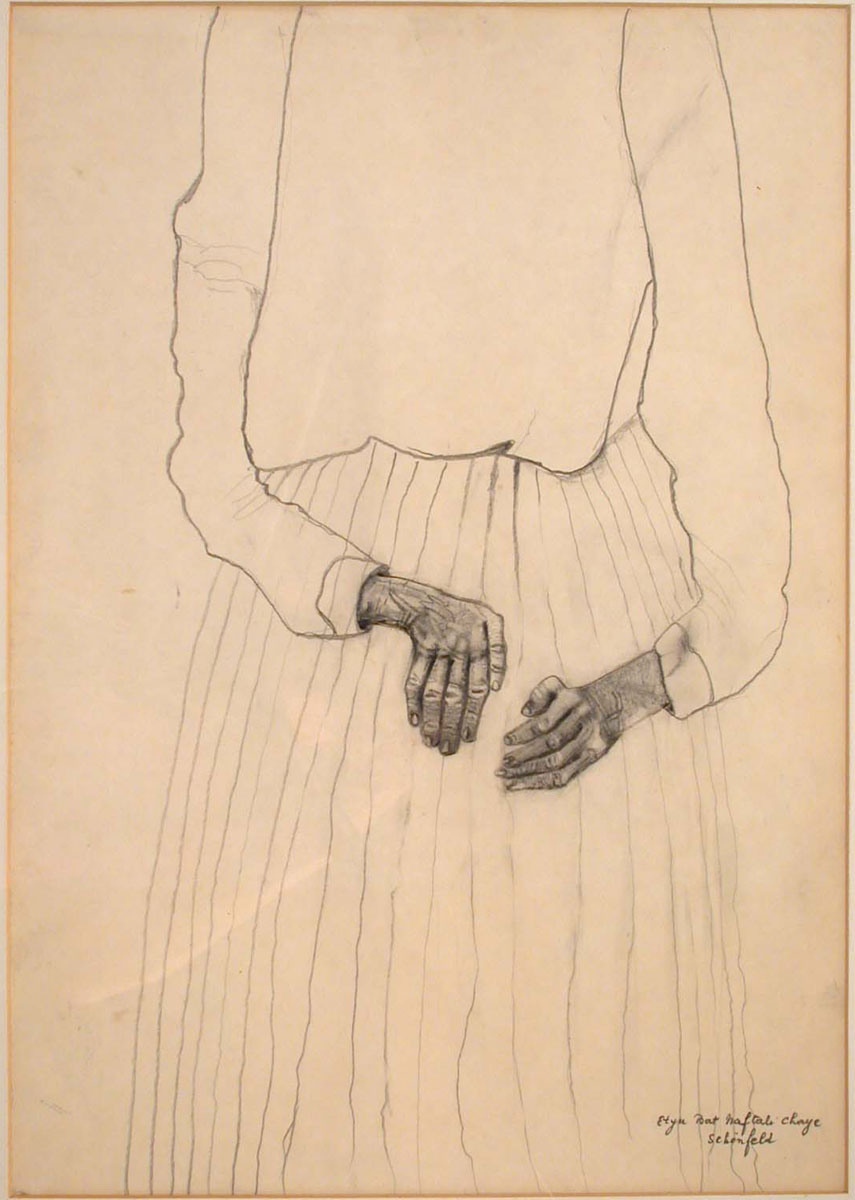

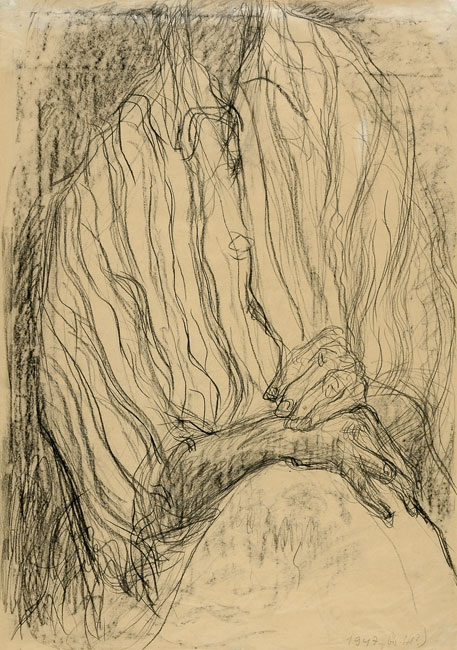

Ilka Gedo, Self-Portrait, 1947, Chalk on paper, 50x35.2 cm.

Ilka Gedo, “Self-Portrait” and Esther Schoenfeld, “Untitled”

Ilka Gedo’s self-portrait, created in 1947, and Etju (Esther) Schoenfeld’s untitled portrait, have a striking feature in common – both are portraits of subjects without their heads or faces.

Ms. Gedo survived incarceration in the Budapest ghetto in 1944.

Viewing Ms. Gedo’s self-portrait, we can only guess at the inner dialogue that must have taken place before she created this image of herself. She is, literally, faceless. The only thing she has decided to show the viewer are hands, folded in a lap. It is as though the artist was making a definite statement: I will not show who I am; this picture will not give the viewer an entry into my psyche. The viewer will not see my face.

We can only speculate why an artist would draw a faceless self-portrait, but in any event there is a complete lack of identity here. These hands could be anyone’s. Is the lack of identity an expression of shame, or avoidance, or questions left unanswered? Perhaps Ms. Gedo’s experiences can give us some insight. In Budapest, in the summer of 1944, she was forced to move to a house that was designated for Jews, in an area very close to the ghetto. At first, this building was part of the emergency ghetto hospital, which later became a shelter for abandoned children – these children recur in some of her other drawings. The situation of the Jews in Budapest worsened in the fall of 1944; thousands of Jews were deported. She was in great danger on two occasions but managed to escape: once because there were not enough railway cars to deport all the Jews from the station, and once when she hid during a search by the police. When the police ordered her to report to them, calling her name, an old rabbi, with a thin female voice, shouted “Present!” By responding to the police, he saved her life (and undoubtedly lost his). The police never found Ilka. Conditions in the Budapest ghetto were awful – while the city was under siege the dead could not be buried but were placed at the end of the yard of the huge tenement house where Ilka lived and covered with cardboard3. Perhaps one of these incidents was the genesis for Ilka’s loss of identity, or her avoidance of it – perhaps she literally could not look herself in the eyes after another man gave his life for hers?

Esther Schoenfeld’s portrait is, similarly, a subject without a head or a face, but in this case, the hands are more expressive. In this pencil sketch on paper, they are the only thing emphasized – the rest of the body shown is just a series of simple lines. The hands, though, are shaded and filled in. At the same time, they seem twisted and withered, possibly arthritic. They even seem to be smaller than the lines that compose the rest of the body. What is Ms. Schoenfeld trying to say? Is this, too, an expression of shame or disgust at the things these hands were forced to do? Did this woman lose her identity because of the work of her hands? Does it help to know that Ms. Schoenfeld wandered through Belgium before she was arrested and deported, ultimately to Auschwitz, where she worked as a translator for the infamous Josef Mengele and his wife? Perhaps there is an oblique reference to her experiences at Bergen Belsen, where she was liberated. Perhaps this is a portrait of a woman whose hands are the only thing she recognizes as her own after all the traumatic experiences she underwent. Perhaps her face would not show her identity as well as her hands do.

- 3. 3

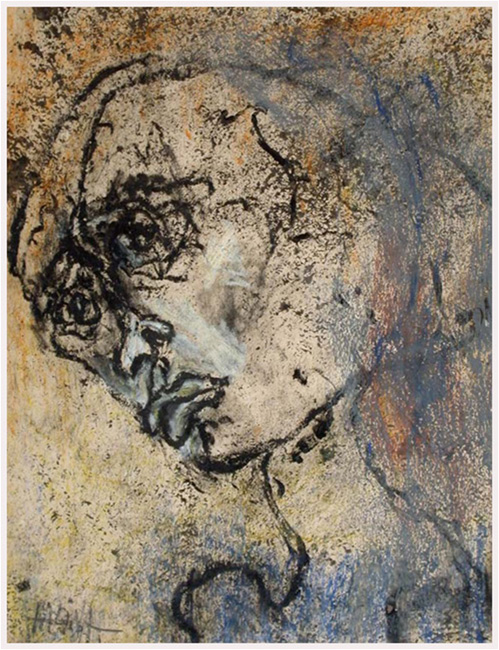

Halina Olomucki, “When Will It End? Enough! Enough!”

This portrait, by Halina Olomucki, has a revealing name: “When Will It End? Enough! Enough!” The drawing was created by the artist in 1955 as part of the cycle called “Camp”. The face expresses hopelessness and despair. The head seems to be bald, or shaved – it looks like a bare skull, at least on top. The right side of the picture – that is, the back of the skull – seems almost to be flying apart. In contrast with the solid black lines of the facial features detailing the eyes, the bags under the eyes, the raised eyebrows, the nose, the mouth, all of which are very definite, the back of the skull is smudged and rubbed, with extra lines emanating from it. It seems to be coming apart somehow.

As opposed to a conventional portrait meant to show a specific person’s exterior likeness, this portrait seems to show the subject’s inner turmoil. It shows angst, anguish and suffering. It mirrors the title of the work very forcefully.

Knowing something about the artist provides us with additional clues. Halina Olomucki was born in Warsaw on November 24, 1919. She was 18 when World War II broke out and, like the other Jews of Warsaw, she was trapped in the Warsaw ghetto. Halina worked outside the ghetto. In order to help her family, she smuggled food in from the “Aryan” side of Warsaw. However, what really kept her alive was creating art – she had an unstoppable urge to create even in the ghetto:

I need to point out […] the most important point. My observation, my need to observe what was going on, was stronger than my body. It was a need, a driving need. It was the most important. I never thought rationally what I am doing, but I had this incredible need to draw, to write down what was happening. I was in the same condition as every other person all around me, I saw them close to death but I never thought of myself close to death. I was in the air. I was outside my existence. My job was simply to write down, to draw what was happening.4

She was deported to Majdanek where she was separated from her mother, who was murdered there. She managed to escape being sent to the gas chamber and art saved her life. In the camp, she was used by the Germans to paint slogans on the walls – the coffee and bread she received in exchange were enough to keep her alive. She continued to decorate barrack walls for the Nazis, and managed to put aside some of the art materials she received so that she could secretly create her own art. She painted many portraits of the women imprisoned with her – portraits unlike the one discussed here, which showed the true likenesses of these women. Later, at Auschwitz as well, prisoners begged her to paint portraits of themselves or of their daughters. This was common in the camps, as many believed that a portrait was their only way of being remembered or commemorated. Olomucki has stated that the faces of the prisoners were so deeply etched in her memory that she was able to draw them even years later. She has said, “If ever I do an exhibition I will always exhibit some paintings, some portraits of those women […] because this is the obligation I took upon myself, that always those daughters of those women will be there, as they asked me back in Birkenau.”5

Interestingly, then, the Olomucki portrait shown here is not one of the realistic ones. This portrait is more expressive and means something completely different. Rather than commemorating a specific prisoner or event, this portrait seems to commemorate the state of mind of many of the prisoners in the camps.

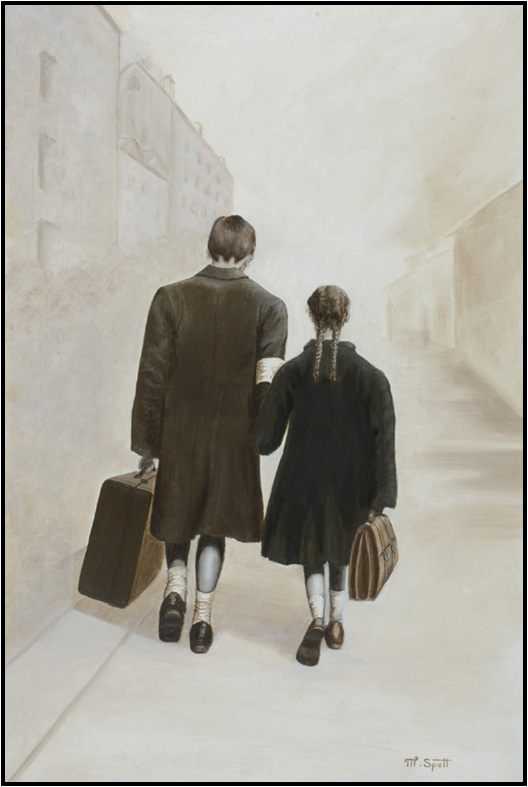

Martin Spett, “My Sister and I”

Martin Spett’s “My Sister and I” is a portrait that quietly speaks volumes about what happened to families during the Holocaust. In the painting, two children, holding each others’ hands, walk down a blurry, vague street. In his free hand, the boy holds a suitcase; in her free hand the girl holds what looks like a book bag, or briefcase. Interestingly, in this picture as well, no faces are visible – we see the subjects of the portrait only from behind. For this reason they are ageless – we know that they are children by the long braids of the little girl and the depiction of both children in short white socks.

The painting is a direct reflection of the crumbling of the family unit during the Holocaust. The two children are shown together – perhaps the “big brother” is taking care of the “little sister” or the children are clinging to each other. The suitcase and bag they are holding indicate that they are being deported; leaving their home. Their parents are nowhere in sight – perhaps they have already been deported or killed. In too many cases, children were forced to grow up way before their time; as their parents were taken away or became helpless, it was the children themselves who stepped up to support their families or had to make their way alone. In this portrait, the children who are the subjects are shown walking into an indistinct, indistinguishable street that must represent the unknown. This seems to be the artist’s way of saying that their future is very uncertain. The viewer almost wants to ask, “What will happen to them?” Will they disappear as 1.5 million children did during the Holocaust?

Samuel Willenberg, “A Father Helping His Son Take Off His Shoes”

This sculpture is also in the nature of a portrait. It is explained more fully in the interview with Samuel Willenberg in this edition of the newsletter. The sculpture can be seen as a form of testimony: this was an event that Willenberg saw himself and, as he says, continues to see before his eyes even today. The prisoners who were brought to Treblinka were forced to undress before they were sent to the gas chambers, so the sculpture/portrait shows what was perhaps this father’s last symbolic act as a parent helping his child. In light of the way this scene ended, with the murder of both, this simple act of removing a shoe becomes a very poignant scene – an act of love that engenders a range of emotions.

Conclusion

For many survivors, commemorating and memorializing their experiences in the Holocaust becomes possible through art rather than words.

There are those survivors who, like Samuel Willenberg, relive their Holocaust experiences all the time, as they go about their daily lives. His sculptures show in bronze what Charlotte Delbo used her writings to convey – that she is still inside the event:

People believe memories grow vague, are erased by time, since nothing endures against the passage of time. That’s the difference; time does not pass over me, over us. It doesn’t undo it. I am not alive. I died in Auschwitz but no one knows it.6

Some survivors use their art to work through the experiences they suffered in the Holocaust – they rework the same themes again and again in order to achieve catharsis. Yet even after they turn to more “carefree” subjects, some sooner or later return to the Holocaust because they are unable to escape its profound influence. Samuel Bak is a case in point; an exhibition of his art can be found online on the Yad Vashem site.

While some survivors use realism and literal expression, others use more abstract representation. Whatever the art may look like, there can be no doubt that survivor art is a very sincere, and very intimate, attempt to document, testify, tell a personal story and commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. In order to do so, the survivor must undergo what is undoubtedly a painful process, which forces her "to gird on the strength to return to hell. To start painting in trepidation, with convulsed guts… to venture to open just a narrow chink."7

We have become used to hearing and reading survivors’ testimonies as expressed through words. As seen above, survivors can both remember and pass their memories on to us through art, as well.