- Dicker-Brandeis, On children’s art, 2005, p. 2, Translated from E. Makarova (2000).

- Linney Wix, Aesthetic Empathy in Teaching Art to Children: The Work of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis in Terezin. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 26(4) pp. 152-158 © AATA, Inc. 2009.

- Linney Wix, Aesthetic Empathy in Teaching Art to Children: The Work of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis in Terezin. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 26(4) pp. 152-158 © AATA, Inc. 2009.

- Professor Erna Furman from a letter to Elena Makarova, 1989.

WHEN the Jews were deported to Theresienstadt ghetto from Prague and environs in 1942, they were instructed to bring with them only 50 kilos. The dilemma of how to pack into a suitcase one’s entire past life for an unknown future life must have been a daunting one. What to bring? Most deportees packed clothing, household articles, valuables, photo albums and the like. However, artist and teacher Friedl Dicker-Brandeis used her weight allowance in a different way. After packing a few necessary items of clothing, she chose to fill the rest of her weight quota with art supplies. Her purpose was not to only have material for her own artistic needs, but to ensure that she would have the necessary art supplies on hand to teach art to the hundreds of traumatized children whom she anticipated meeting at journey’s end. This decision was a natural part of who Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was. While most of us can relate to the very human survival instinct of self preservation, of providing first and foremost for oneself and one’s family, her choice to give of herself to others - to donate her time, her talents and her indomitable spirit – is a much rarer quality, one that still has the power to captivate and inspire us 70 years later.

Friedl was born in 1898 in Vienna, Austria. She was a little girl who lost her mother at a very early age, a loss which she felt keenly her entire life. Although she and her husband, Pavel Brandeis, never had any children of their own, in Theresienstadt Friedl was finally able to give free rein to her maternal instincts, and to nurture, and teach hundreds of children who saw her as a surrogate mother.

From an early age, Friedl pursued a life of art and creativity. She studied in the Weimar Bauhaus under such luminaries as Johannes Itten and Paul Klee. The Bauhaus was not merely a design academy, but an entire philosophy, based on the aesthetics of empathy. Its students were encouraged not to approach an object or subject as if they were a camera, aiming to merely depict the shallow outer shell, but rather to seek the subject’s essence, to see it both inside and out, to become one with their subject, to empathize with it. This philosophy would become the core of Friedl’s own artwork and her guiding principle for teaching art to children, a calling that would come into its own in Theresienstadt.

In mid 1938, Friedl had obtained Czech citizenship and she and her husband, Pavel Brandeis were living in Harnov, Czechoslovakia. It was from there that they were deported to Theresienstadt, on Dec 17th, 1942.

Conditions in Theresienstadt were appalling, and even more so for children who had to first cope with the enormous trauma and life-changing upheaval that deportation wreaked upon their young lives. The Czech children who were deported to Theresienstadt had slept in their beds until the day they were deported, and were together with their immediate families until the moment they arrived. Children were ripped away from the familiarity of their homes, families, communities and routines and thrust into a terrifying new reality which they could not understand. Upon arrival in Theresienstadt, children were forcefully separated from their parents and family and sent to live alone in overcrowded children’s houses; even brothers and sisters were separated because boys had to live separately from girls. The starvation, illness and brutality of Theresienstadt, along with lack of stability and structure, put an enormous strain on the coping mechanisms of these children. They desperately needed direction and purpose, and Friedl was there to give them that.

Realizing that art could be a therapeutic tool to help children to deal with their feelings of loss, sorrow, fear, and uncertainty, Friedl set about teaching over 600 children with the enormous enthusiasm and energy that her friends, colleagues and students remember as being so typical for her. Using the limited art supplies she had brought with her to the ghetto, she had her students explore various mediums such as collage, watercolor painting, paper weaving, and drawing. But her lessons were not designed merely to teach her students technique. Rather, these different techniques became the means through which she taught her young students to dig below the facile to the deep well-spring of their feelings and emotions, and from that intimate place, to create. Through this intuitive method, a drawing of a flower vase on a windowsill, or the portrait of a child, would become something truly absorbed, deeply felt, sublime. It would reflect the child’s inner feelings - a window into their soul. In a lecture she gave in the ghetto in 1943 to explain her teaching methods, she declared that her purpose was not to train the children as artists, but rather to “unlock and preserve for all the creative spirit as a source of energy to stimulate fantasy and imagination and strengthen children’s ability to judge, appreciate, observe, [and] endure” by helping children choose and elaborate their own forms.”1

- 1. 1

Friedl respected the boundless imagination of children, and did not try to curb her students with adult restrictions, but tried rather to harness that imagination and let it move them. For Friedl, artwork represented freedom, and that freedom could take her students outside the boundaries of their prison, outside of the horror and oppression that was their daily reality. One of Friedl’s few students that survived the Holocaust, Helga Kinsky (nee Pollak), recalls how under Friedl's tutelage, the children did not depict the misery and horror that surrounded them, but rather that Friedl “transported us to a different world…. She painted flowers in windows, a view out of a window. She had a totally different approach…. She didn’t make us draw Terezin.”2

Another surviving student, Eva Dorian said of her beloved teacher: “I believe that what she wanted from us was not directly linked to drawing, but rather to the expression of different feelings, to the liberation from our fears…these were not normal lessons, but lessons in emancipated meditation”3.

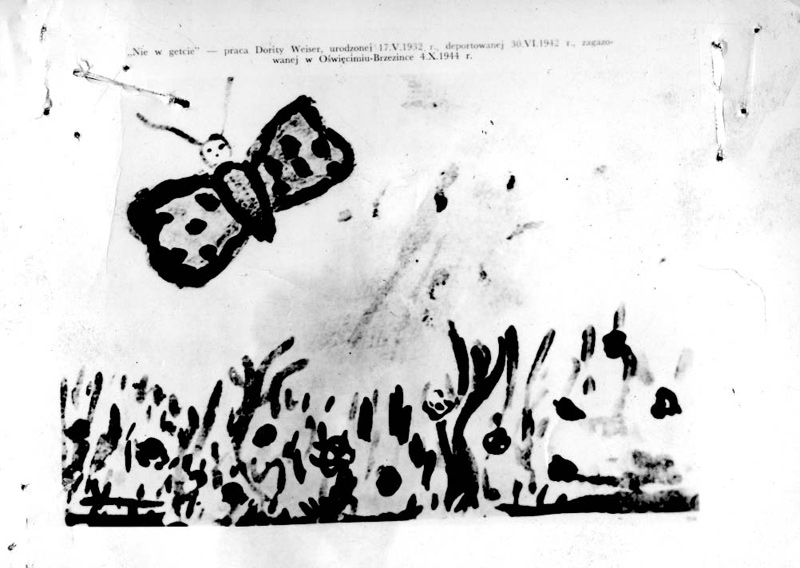

None of these attempts of art as therapy, of spiritual freedom through paints and paper, could change the dreadful reality that awaited the majority of the Jews of Theresienstadt. When Friedl's husband Pavel was deported from Theresienstadt in late September 1944, she voluntarily signed up for the next transport, desperate to reunite with him. But what was to become of her collection of the children’s precious artwork and her own beautiful drawings and paintings? Hoping that eyes more sympathetic than the Nazis’ would one day see them, she packed 5,000 pieces of artwork into the same 2 suitcases they had arrived in as raw materials in 1942, and hid them, to be found after the war. Although Friedl herself did not sign most of the work she produced in Theresienstadt, she made sure that the children signed their creations with their name and age, a testimony to their identity, a document of their existence. These drawings and signatures are all that remains of most of Friedl’s 600 students. Apart from their ages and names, the overall majority will remain forever unknown, murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz Birkenau, starved to death in Theresienstadt or killed by the inhuman conditions of other camps.

On October 6th, 1944, Friedl Dicker Brandeis and 60 of her students were sent on transport number EO 167 to Auschwitz Birkenau, where most of them were probably murdered upon arrival. Until the very end, Friedl did not resign herself to despair or allow her young students to become engulfed by hopelessness. Rather, as one of the first practioners of art therapy, she gave them the gift of expression, artistic freedom and beauty and helped give meaning to their young lives, for as long as they still had to live. One of her former students sums up succinctly what Friedl meant to her:

"Friedl's teaching, the times spent drawing with her, are among the fondest memories of my life. The fact that it was Terezin made it more poignant but it would have been the same anywhere in the world… I think Friedl was the only one who taught without ever asking for anything in return. She just gave of herself."4

Through her solidarity with those in need, the giving of herself to help others to cope, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis – artist, teacher, and spiritual mother – inspires us as much today as she did her own students 70 years ago.