- Zurach Warhaftig, Uprooted (New York: Institute of Jewish Affairs of the American Jewish Congress and World Jewish Congress, 1946), p. 37.

- Ibid., p. 37.

- The Joint had been formed by a number of religious, political and other lay organizations to provide help for the European Jewish civilian population during World War I. It ranked second in size only to the Red Cross as a worldwide relief organization following World War II, and it focused its efforts on survivors of the Holocaust.

- Earl G. Harrison, Report to President Truman on The Plight of the Displaced Jews in Europe, released by the White House on September 29, 1945, reprinted by United Jewish Appeal for Refugees, Overseas Needs and Palestine, New York, 1945, pp. 4-5.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Ibid., pp. 6-7.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Shapira & Keinan.

- Belsen. Tel Aviv: Irgun Sheerit Hapletah Me'ezor Habriti, 1958, p. 119. (Hebrew). April 15, 1945 was the date that the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated by the Allies.

- Michael Berenbaum, The World Must Know (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1993), p. 208.

- Hagit Lavsky, New Beginnings: Holocaust Survivors in Bergen-Belsen and the British Zone in Germany, 1945-1950 (Detroit: Wayne University State Press, 2002), pp. 149-150.

- Video testimony of Shoshana Roshkovski in The Displaced Persons Camps, 2005, directed by Ayelet Heler.

- Hagit Lavsky, New Beginnings: Holocaust Survivors in Bergen-Belsen and the British Zone in Germany, 1945-1950 (Detroit: Wayne University State Press, 2002), p. 150.

- Testimony of Eliezer Adler, Yad Vashem Archive, 03/5426, pp. 41-42 (Hebrew).

- Yad Vashem O.69/102.

- Video testimony of Shoshana Roshkovski in The Displaced Persons Camps, 2005, directed by Ayelet Heler.

- Ibid.

When World War II ended and the German occupied territories were liberated by the Allied soldiers, those soldiers encountered hundreds of thousands of Jews who had survived the Holocaust. These people had survived years in hiding, in the ghettos or camps. Now that they were liberated many tried immediately to return to their homes. There they faced many difficulties. They suddenly realized that they had no place to go. Their homes, families, friends, entire villages and towns didn't exist anymore. In some places, particularly in Eastern Europe, survivors who had returned home encountered antisemitism and were met with violent hostility. As discussed in a different article in this newsletter issue, in Kielce, 42 Jews who had survived the Holocaust were killed by local Poles in a pogrom on July 4, 1946.

Background of the DP Camps

As early as 1943 the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration was created at a 44-nation conference in anticipation of the liberation of Europe and the problem of displaced persons and refugees. The UNRRA was intended to give economic and social aid to countries that had been under Nazi occupation, and to help repatriate the displaced persons. A distinction was made between “refugees” and “displaced persons.” The former were defined as those who fled from their homelands without being able to return, and were to be cared for by the Inter-Governmental Committee on Refugees (the IGCR) which was created following the Evian Conference in 1938. The latter were defined as those uprooted by the war. This included millions of people who had been deported by the Nazis to forced labor and concentration camps, or who had fled their bombed hometowns. They were expected to return to their native countries. In the meanwhile, they were to be placed in assembly centers, or displaced persons (DP) camps. These displaced persons (DP) camps were in the occupied zones of Germany, Austria and Italy. Until the second half of 1946 there was an increasing movement of refugees from east to west, and at the beginning of 1947 the number of Jewish displaced persons stabilized at around 210,000. Most of them – about 175,000 – were in Germany in the American zone.

Four main stages of assistance to displaced persons were defined: rescue, relief, rehabilitation and reconstruction. These stages were not defined by sharp calendar distinctions; in some cases rehabilitation and relief began simultaneously, while in others, one phase extended into the next. European Jewry presented an acute and unique problem: Jews, who constituted twenty-five percent of the general population of displaced persons, were frozen in the period of urgent rescue operations.1 They suffered from malnutrition, from depression and from disease. Many who had narrowly escaped death when their concentration and labor camps were liberated by the Allied forces continued to remain in these camps months after liberation, still behind barbed wire, still subsisting on inadequate amounts of food and still suffering from shortages of clothing, medicine and supplies. Death rates remained high. In Bergen-Belsen, an infamous concentration camp that was transformed into a displaced persons camp, there were over 23,000 deaths within three months after liberation, 90% of them Jewish.2

Conditions in the DP Camps

On June 22, 1945, U.S. President Truman requested Earl G. Harrison, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School and the newly-appointed American delegate to the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, as his personal envoy to prepare a report on the situation of the displaced Jews in Europe. Harrison made a 3-week long inspection tour of the DP camps, accompanied by Dr. Joseph Schwartz, a representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint).3 Harrison presented his findings in a report to President Truman, quoted below.

"Generally speaking [...] many Jewish displaced persons and other possibly non-repatriables are living under guard behind barbed-wire fences, in camps of several descriptions (built by the Germans for slave-laborers and Jews), including some of the most notorious of the concentration camps, amidst crowded, frequently unsanitary and generally grim conditions, in complete idleness, with no opportunity, except surreptitiously, to communicate with the outside world, waiting, hoping for some word of encouragement and action in their behalf [...] there are many pathetic malnutrition cases both among the hospitalized and in the general population of the camps [...] there is a marked and serious lack of needed medical supplies [...] many of the Jewish displaced persons, late in July, had no clothing other than their concentration camp garb […] while others, to their chagrin, were obliged to wear German S.S. uniforms. […]

Beyond knowing that they are no longer in danger of the gas chambers, torture and other forms of violent death, they see – and there is – little change, the morale of those who are either stateless or who do not wish to return to their countries of nationality is very low. They have witnessed great activity and efficiency in returning people to their homes, but they hear or see nothing in the way of plans for them and consequently they wonder and frequently ask what 'liberation' means. [...]

The most absorbing worry of these Nazi and war victims concerns relatives, wives, husbands, parents, children. Most of them have been separated for three, four or five years and they cannot understand why the liberators should not have undertaken immediately the organized effort to reunite family groups. Most of the very little which has been done (to reunite families) has been informal action by the displaced persons themselves with the aid of devoted Army Chaplains, frequently Rabbis, and the American Joint Distribution Committee."4

Harrison was shocked by what he saw in the DP camps. He did not mince words in his report to President Truman. The report was a ringing condemnation of the way Jewish displaced persons were being treated, and was aimed at provoking quick action by the United States.

"As matters now stand, we appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except that we do not exterminate them. They are in concentration camps in large numbers under our military guard instead of S.S. troops."5

Harrison’s report greatly influenced President Truman. It led to some improvement in the conditions in the camps. One of the first measures implemented was to separate the Jews from the rest of the population of displaced persons.

The DP camps had, until then, been arranged according to nationality. Army administrators of the camps had thus forced the Jews to live in the camps together with displaced Germans and Austrians, for example, many of whom had been Nazi collaborators. In addition, despite the traumas they had lived through, Jewish displaced persons were being treated the same way as other DPs. Harrison understood that the situation of the Jews was unique, and that they needed to be treated differently than the other displaced persons.

"The first and plainest need of these people is a recognition of their actual status and by this I mean their status as Jews. Most of them have spent years in the worst of the concentration camps. In many cases, although the full extent is not yet known, they are the sole survivors of their families and many have been through the agony of witnessing the destruction of their loved ones. Understandably, therefore, their present condition, physical and mental, is far worse than that of other groups. […] While admittedly it is not normally desirable to set aside particular racial or religious groups from their nationality categories, the plain truth is that this was done for so long by the Nazis that a group has been created which has special needs. Jews as Jews (not members of their own nationality groups) have been more severely victimized than the non-Jewish members of the same or other nationalities."6

Harrison concluded that a stronger effort needed to be made to get the Jews out of the camps, because “they are sick of living in camps.”7 In addition, he pointed out the real need for rest homes for those who needed a period of readjustment and training before living in the world.

Despite the difficulties of life in the DP camps, the Jewish refugees had “an almost obsessive desire to live normal lives again.”8 This description, given by Leo Srole, the director of UNRRA activities at Landsberg, among the largest of the DP camps in the American zone of Germany, indicates the mental state of the Jewish refugees who had survived the Holocaust. Contrary to what might be expected, there was almost no talk of vengeance. Zalman Grinberg, a Holocaust survivor, said in a speech to other survivors, “We don’t want revenge.” For the Jewish survivors, the best revenge was to rebuild their lives. As discussed below, perhaps the most important facet of this rebuilding was to reestablish families that had been torn apart, and to have children and raise a new generation of Jews to make up for those who had been wiped out by the Nazis.

Return to Life in the DP Camps

Some survivors were not able to overcome the tragedy that had fallen upon them. Most, however, could not wait to start living and try to make up for the years they had lost. Life in the DP camps was full of vitality and intensity, as though the survivors were trying to make up all at once for lost time. Food and clothing were in short supply, space was at a premium and privacy was almost non-existent, but the Jewish refugees managed even with these limitations. There were educational activities, occupational and vocational training, for those who had missed years and years of schooling and had no marketable trades. Kindergartens and makeshift schools were set up for the few children who had survived. There were cultural activities, including newspapers and magazines published in Yiddish. Religious material was published, especially in the realms of Jewish law that concerned the survivors, such as missing spouses and ritual purity. There were theater performances and plays, where the DPs themselves performed. In addition, holidays were celebrated and even parades were organized.

Holocaust survivor Paul Trepman, who was a member of the Jewish leadership in the DP camp at Bergen-Belsen, describes life there in his testimony:

"Teachers established good schools, from nothing. People produced quality newspapers that were worth reading, even without a press. Actors established a theater. All of this was in addition to meeting the daily needs of the new Jewish community in the camp.

Of course, over time, we received help from outside. But we laid the foundation for this new community, we built it and ran it ourselves. We received food and books from outside, but we did the work and we can be proud of our efforts. Those who survived will always remember April 15, 1945 as their second birthday - in many ways more important than their first."9

Weddings in the DP Camps

More than anything else, though, the vitality of the refugees was expressed in their intense desire for human relationships. Most of them found themselves entirely alone, having lost their parents, spouses, children and siblings during the Holocaust. At first this was manifested in heartrending searches for relatives and anyone connected to their prewar lives. Individuals who came from the same town or the same city and even chance acquaintances became close friends. People from the same town grouped together, and the group became a substitute for the lost family. These searches developed from initial spontaneous initiatives by army chaplains to an organized system run by the Joint. The search for relatives, as a daily radio program broadcast in Israel, continued to function for many years.

The drive to reestablish a normal life, and to banish the despair and loneliness of being a survivor, was expressed in the yearning to find love and friendship. Many of the survivors were young men and women between twenty and thirty, who were all alone in the world, their relatives having perished. Psychologically, in many cases, it was easier for survivors who had lost their spouses to understand and relate to other survivors in the same predicament. They understood each other. Forming couples led to rehabilitation and normalization in a very abnormal environment. The post-war marriages were not always based on love; fear of loneliness and the need for companionship motivated many marriages. One DP who had lost his family proposed to another DP with these words, “I am alone. I have no one, I have lost everything. You are alone. You have no one. You have lost everything. Let us be alone together.”10

"Much attention was paid to weddings, and very often they were the main agenda in the social life of the camp. During the first year after liberation there were numerous weddings, not uncommonly six or more in a single day, even fifty in a week. During 1946 there were 1,070 weddings. But statistics, as impressive as they may appear, do not convey the atmosphere surrounding the weddings. To get married had many bright, as well as sad, aspects, reflecting the essence of being a survivor in a DP camp. First there was a question of halakah (Jewish law). Most couples decided to be married in a Jewish wedding ceremony. It was not just a question of being religious. Even for the secular, it meant forming a new link with the past, overcoming the disaster and continuing the family chain, being Jewish and keeping and manifesting the Jewish tradition. […] The invitations and the descriptions of individual weddings often, however, reflect the dark side of the event. Many invitations are signed by the bride and bridegroom, with no father or mother inviting guests to their children’s wedding. Sometimes the name of a single relative – an uncle or a cousin – appears, further emphasizing the tragedy behind the scenes. The ceremony itself was painful. The mention of loved ones who were absent sadly demonstrated the dark holes in the circle of family and friends." 11

A case in point was the wedding of Abraham and Shoshana Roshkovski, one of seven couples who got married on May 19, 1945 in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp. They had not known each other for very long, but when he suggested that they marry, she agreed. Shoshana’s bridal gown was a black skirt and a borrowed shirt that was too big for her; her veil was made of a gauze bandage. “We got up to dance just to forget our sadness,”12 Shoshana remembered later. Every wedding was a celebration for the whole camp.

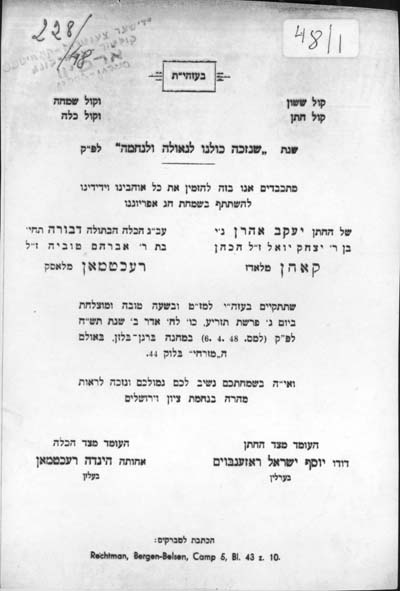

- Invitation to Fryda and Zygmunt's wedding, Bergen Belsen, 1948 (German and Yiddish original)

- Invitation to Golda and Menashe's wedding, Bergen Belsen, 1948 (Hebrew original)

- Ketubbah (Jewish marriage contract), Bergen Belsen, 1946 (Hebrew original)

- Ketubbah (Jewish marriage contract), Bergen Belsen (English original)

- Jewish marriage license, Central Jewish Committee, Bergen Belsen (English original)

Childbirth in the DP Camps

In the first months after the war there were barely any children under the age of 5 in the DP camps, and only 3% of the survivors were children and teenagers aged 6-17. Most survivors had lost their entire families, and alongside the feelings of loss and loneliness was the yearning to establish families of their own. Many women had stopped menstruating in the concentration camps. Now, they were mortified that they might never have a child. They wanted a child eagerly to prove to themselves that they were still viable human beings. Recreating a family was seen as an act of defiance against Nazi Germany. Children became the symbol of renewal and normalcy. They were seen as the continuation of the chain that had been severed with the annihilation of an entire generation of Jewish children by Nazi Germany, which saw these children as latent parasites and destructive elements who carried with them the heritage of their race. The birth rate in the camps was among the highest in the world at that time. In Bergen-Belsen alone, 555 babies were born in 1946.13 The growing rates of pregnancies and births expressed a deep-seated Jewish need; it was as if a child was the personal contribution of each survivor to the continued existence of the Jewish people.

Eliezer Adler was born in 1923 in Belz, Poland. He spent most of WWII in a forced labor camp in the Soviet Union. After the war Eliezer spent three years in DP camps. He recalled:

"...This issue of the rehabilitation of She'arit Hapleta ("surviving remnant"), the Jews' desire to live, is unbelievable. People got married; they would take a hut and divide it into ten tiny rooms for ten couples. The desire for life overcame everything - in spite of everything I am alive, and even living with intensity. When I look back today on those three years in Germany I am amazed. We took children and turned them into human beings, we published a newspaper; we breathed life into those bones. The great reckoning with the Holocaust? Who bothered about that... you knew the reality, you knew you had no family, that you were alone, that you had to do something. You were busy doing things. I remember that I used to tell the young people: Forgetfulness is a great thing. A person can forget, because if they couldn't forget they couldn't build a new life. After such a destruction to build a new life, to get married, to bring children into the world? In forgetfulness lay the ability to create a new life... somehow, the desire for life was so strong that it kept us alive…" 14

For some survivors, however, it was not easy to make the decision to start a new family. Women who became pregnant shortly after the Holocaust had not always regained full strength and health. They and their babies were often in danger. There was a constant shortage of proper nutrition in the DP camp, undernourished mothers found it difficult to breastfeed, and there was not enough baby food in the DP camps. The fact that new mothers did not usually have guidance from their own mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, or female friends, as they would have had in previous happier times, also posed a challenge. In her testimony, Judy Rosenzweig reflects on the decision to give birth after liberation:

"It was not an easy decision on my part at the very beginning of my liberation to ever bring another Jewish child to the world. But soon enough my life began to take a more normal route, so to speak. And God blessed us with two beautiful children."15

However, there were also emotional issues that made it very difficult for women to have children as Holocaust survivor Shoshana Roshkovski describes in her testimony:

"During and after the war, girls didn't get their periods. I got married and became pregnant, I didn't know I was pregnant. [...] [The doctor] examined me and said, 'You're three months pregnant.' I jumped off the table like a mad woman, 'Doctor, I'm pregnant?' He said, 'You're not married?' I said, 'I'm married, but I don't want a baby, I want an abortion, I don't want a child. I can't hear a baby crying, I heard babies screaming in Auschwitz, I don't want it.' I cried terribly." 16

She remembers how everything changed when her son was born:

"[W]hen they brought him to me, and I saw him alive, I thought of how I had wanted to kill him. I thought about it all the time and prayed that God would let me keep him, that he wouldn't get sick." 17

Conclusion

In April 1948, one month before the establishment of the State of Israel, there were still 165,000 Jewish DPs in Germany. With the establishment of the State of Israel about two-thirds of the DPs emigrated to Israel, while most of the others moved to the United States of America. Within five months the number dropped to 30,000. Most DPs followed in the next years; only a small minority stayed behind, unable or unwilling to leave. The last DP camp, in Fohrenwald, closed in February 1957.