In 1791, after the French Revolution, Jews in France were emancipated and granted full citizenship. This was the first time in history, that Jews had been given such equality. Even after the Dreyfus Affair in the 1890s, French Jewry remained convinced that their place as equals in society would ultimately keep them safe from antisemitism that existed in other European countries. Unfortunately, this was not the case.

As is pointed out later in this article, the motto of “liberty, equality, fraternity,” was turned on its head by the Germans when they invaded in May 1940. There is a long history of Jews in France, but this newsletter focuses solely on the period during World War II and the Holocaust.

Any study concerning the numbers of Jews saved in the various occupied countries of Europe during the Second World War has to take into account the specific factors at play in each country. This essay will deal specifically with the saving of Jews in France, taking into account the political tradition of France, and the special circumstances that evolved in the country from the fall of Paris in mid-1940.

The story of France under German occupation is unique as compared to other Nazi-occupied countries, because the Germans controlled the north, while the south was governed by the Vichy regime. Therefore, there are really two stories about Jews in France during the Holocaust. There were the Jews who lived in northern France under German occupation, and the Jews who lived in southern France being governed by the Vichy government. Before World War II, 43 million people lived in France, among them between 300,000 and 330,000 Jews. This Jewish community was diverse; 90,000 were well established in France for many generations, and the rest were émigrés from a variety of European countries. Beginning in the 1880s, Jews immigrated from Russia, Romania, and Poland, and after World War I, from the newly created states of Poland, the Baltic countries, Hungary, and Romania.

The figures of Jews saved in France are impressive. Germany invaded France in June 1940, just months after she occupied Denmark and Norway, Belgium, and Holland. An oppressive German occupation in Paris remained in effect for just over four years until the liberation of the capital in August, 1944. Despite this long period marked by anti-Jewish enactments of Nazi ideology and policy, the number of Jews deported to their deaths was lower than in all the other western European countries occupied by German forces during the war. Figures available to us from research indicate that seventy-five percent of French Jewry survived.

Factors Determining the Fate of Jews in France

There are many factors that contributed to the relative failure of the murderous Nazi intentions to come to fruition in occupied France. Some go back to the achievements made two centuries prior, and others enumerated below take into account specific aspects of the French reality in the twentieth century.

1. The Historical Legacy

The Jews of France had already enjoyed one hundred and fifty years of civil rights, fruits of the French Revolution and the emancipation of the Napoleonic era. In contrast, the German attempt during the Weimar Republic at entrenching a democratic regime beginning in 1918 failed dismally after only fifteen years with the Nazi takeover in 1933 in Germany. The invading German forces on French soil in 1940 then attempted to roll the achievements of the French Enlightenment backwards by issuing orders designed to initially strip the Jews in France of their civil rights and ultimately to deport them to their deaths in the “Final Solution.”

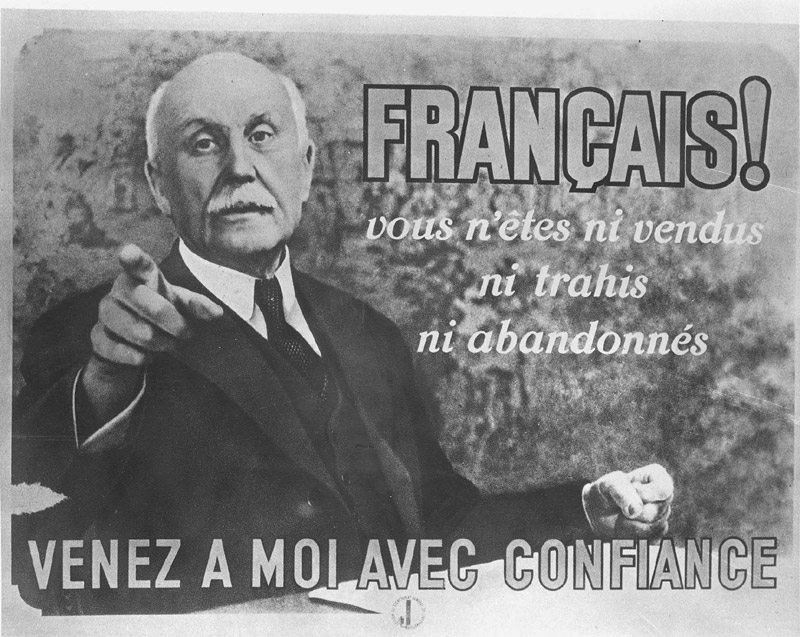

In the wider perspective of national character and the legacy embodied in liberté, fraternité and egalité from the eighteenth century, Jews enjoyed a high level of integration into French society as individuals and the matter of their religious affiliation was of less import with the modernizing and secularizing directions of French society. Whatever the official line of the German forces in the north or of the French authority under General Petain in the south, Jews could very often draw on their personal connections in French society which had, prior to the German invasion, been accepting and integrating.

2. The Church in France

Many Church leaders were active in their role as Christian community leaders in condemning German policy toward Jews. Amongst pastoral letters that were widely disseminated in Christian circles, one written by Cardinal Saliege of Toulouse and read in many parishes by the local priest, spoke out in plain language reminding the French of their obligation to all peoples being hounded by the Germans, including the Jews.

The wonderful example of the parish priest Andre Trocme in the Protestant village of Le Chambon sur Lignon and the saving of so many Jews in this village is a shining light in the history of Christian/Jewish relations in France.

3. Three Distinct Zones of Administration

The Germans faced a complex reality in France, which made the implementation of their designs more difficult, and also increased the chances of escape. The first main obstacle for the Germans was the division of France into the northern, occupied zone and the southern unoccupied zone, the latter of which was run by the French as the Vichy Administration under General Petain. The immediate result was the constant flow of Jews from the north to the south over the demarcation line. Added to this was the differentiation created between Jews born in France and foreign Jews who had recently arrived and were living in France, many of them refugees from Germany and Austria. In the first stages of the occupation, French Jews were exempt from deportation orders and many fled south. A remarkable point is offered us in 1943 when the Germans pressured Petain to denaturalize this group of Jews now in his area of jurisdiction to enable the Germans to deport them more easily; Petain proved at this particular instant not to act as a cog in the wheel of German designs – he refused to sign the decree. Add to the above two zones the Italian zone of influence in southeast France and we are looking at the further frustration of German deportation plans, since Jews could now exploit this avenue of escape until the German occupation of Italy later in the war.

4. Jewish Activism

Without Jewish activism, the high percentage of Jews saved in France would hardly be explicable or comprehensible. Venerable organizations like the OSE - The Children’s Aid Society (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants), the Jewish Scouts, ORT (Professional Retraining and Work Committee) and many other organizations that had relocated south after the occupation of the north, were very active in all kinds of relief work and in saving Jewish lives in France.

The OSE, which had originally been founded in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1912 as a society geared to improving the general health of Russian Jews, spread its wings of aid to other centers in Europe during the twenties until eventually in 1933, its headquarters were moved from Berlin to Paris. The OSE in France, from its inception, began to deal with Jewish refugee children from Germany and Austria. The special orientation of the OSE from its Russian days of helping doctors and medical aides administer to the health of Jewish communities was extended in France to incorporate the work of dedicated Jewish social workers who worked miracles during the German occupation by helping Jewish children. This work involved many different elements: taking the children out of detention camps, establishing and maintaining children’s homes in different locations, establishing fake identities for the children with fake identification papers and teaching the children not to divulge their real names and identities. The variety of the OSE’s activities extended to dangerous and trying attempts to lead children over borders to Switzerland in the north and across the Pyrenees into Spain in the south.

In the wider perspective of the Holocaust throughout Europe, the numbers of Jews transported to their deaths from France were considerably lower than in most other occupied countries. However, the day-to-day difficulties of living through and surviving the occupation in France are all graphically described in personal accounts, two of which were ironically written by young women who did not survive. Readers are referred to The Journal of Helene Berr, written by Helene Berr, and Suite Française, written by Irene Nemirovsky. Both books succeed in immersing the reader in the fabric and texture of a painful occupation dealt with in general outline in the article above. A book review of Helene Berr’s Journal can be found on our website; a review of Suite Française is found in this newlsetter.