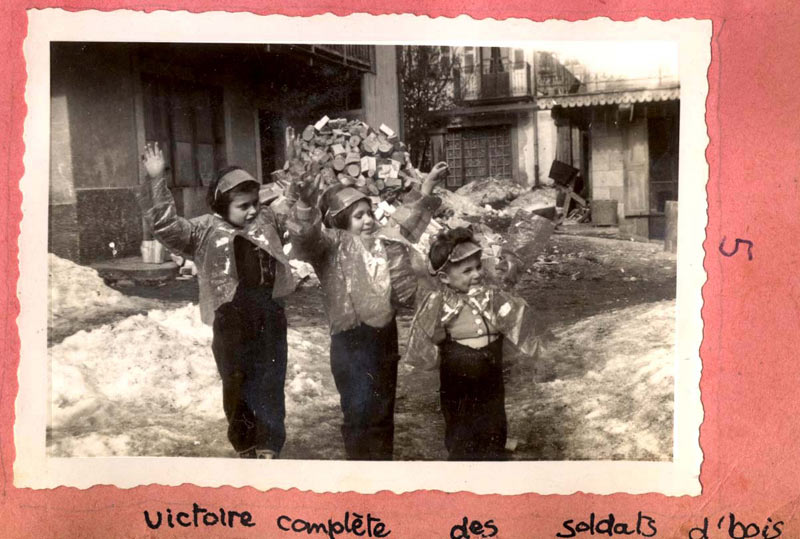

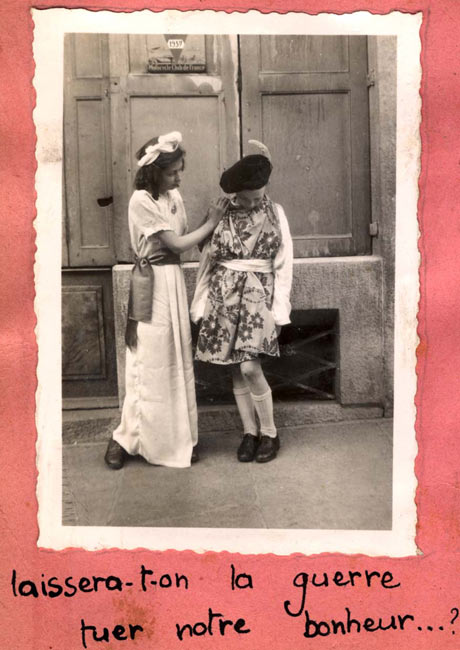

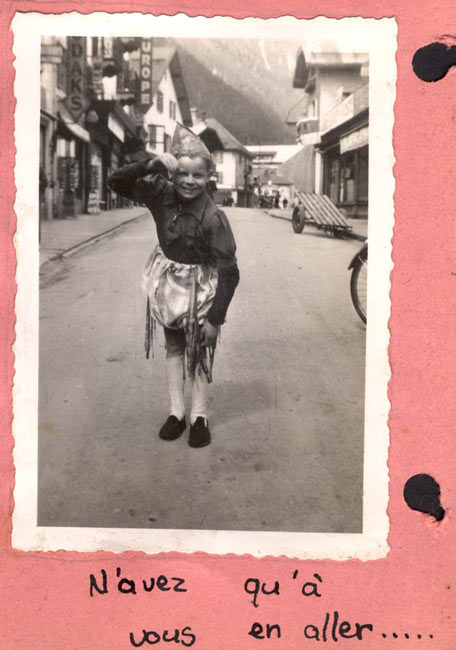

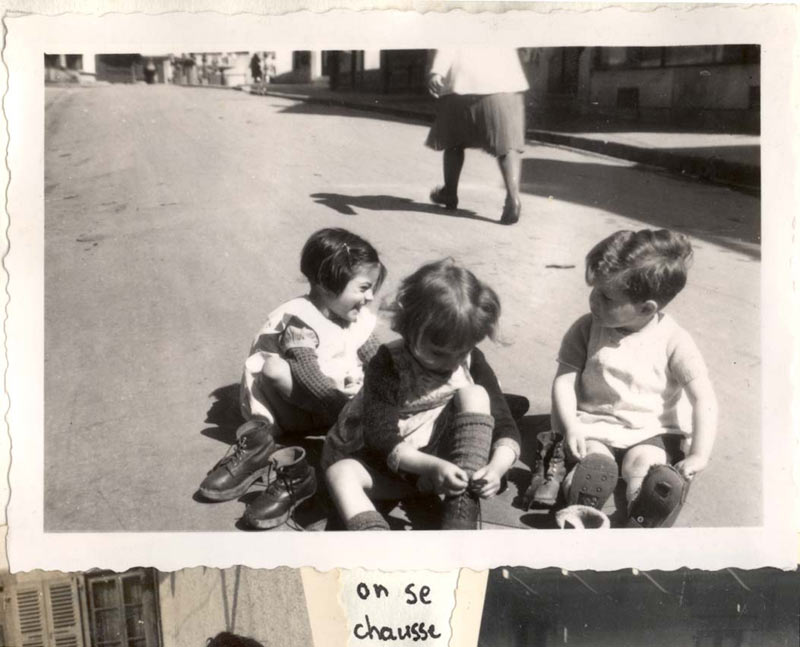

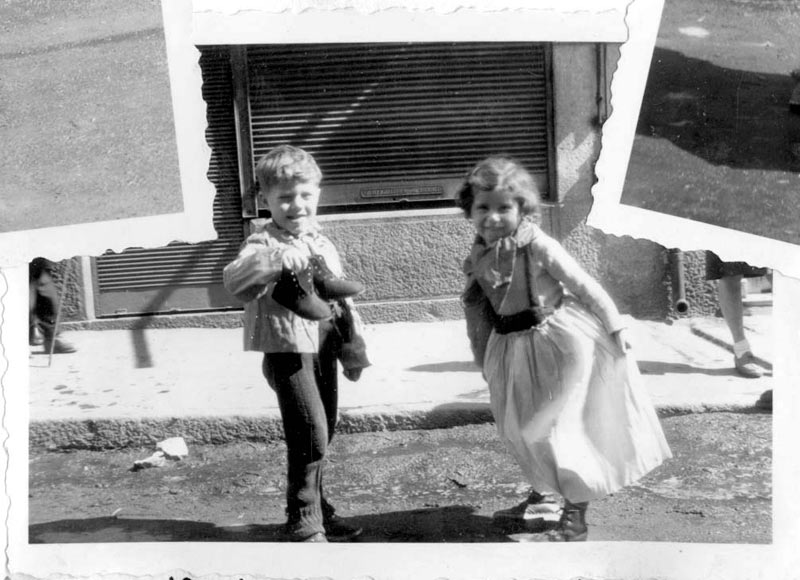

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

Introduction

In June 1940 after Nazi Germany invaded France, the French surrendered and signed an armistice with the Nazis. France was then divided in two: northern France (the occupied zone) was placed under German control, while southern France (the unoccupied zone) was placed under the control of a new French government, which was established in the spa town of Vichy. At that time, approximately 350,000 Jews lived in France, some of whom were refugees from Germany and other countries occupied by the Nazis, including thousands of children.

Almost immediately after the occupation, Jews living in the occupied zone and those in the unoccupied zone were subjected to the first wave of anti- Jewish measures. In the German- controlled zone, Jews were stripped of their jobs, their freedom of movement became restricted, and many were arrested. At the same time, the Vichy government actively commenced persecuting the Jewish community, and in October 1940 a set of laws called the Statut des Juifs was passed.

With the advent of the German occupation, camps were set up and deportations started. Various groups took on the responsibility and risk of attempting to hide Jewish children. Wherever possible, efforts were made to send them on to safety in other countries such as Switzerland and the United States.

Beginning in March 1939, several transports brought children from Germany, Austria, and other countries in Europe to France. Some were brought by families trying to ensure their safety. Each child had his or her own experience during the time they were hidden. Some remained in contact with their families, while others lost contact and were alone, relying only on their “adopted” families.

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

Saint Georges, France - a photograph from a children's home where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust

The Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE)

One major rescuer of Jewish children was the international children's health care and welfare society, which set up an underground children's rescue network known as Circuit Garel. The OSE ran dozens of orphanages, for children from infants to teenagers, whose parents had been murdered or deported. Many of the children came from Germany, Austria, Poland, and other countries already occupied by the Nazis.

The children were schooled and trained according to their ages, and were given special training in physical education and survival skills to better prepare them for possible dangers ahead. The OSE gave assistance to children and adults in as many as fifteen towns and the internment camps in southern France. Care was given to about one thousand three hundred children, some orphans and some whose families had placed them in these facilities. As the Nazis approached Paris in 1940, all the homes were transferred to the unoccupied zone in southern France. After the Nazis moved into southern France, the OSE went underground but continued to hide children and transfer them to Switzerland when that was possible.

The Odyssey of the Frenkel Children

When the war broke out, the Frenkel family tried to escape to England from Belgium, but failed. They journeyed to Montelimar in southern France, where Menachem’s father found work in a nougat factory. In July 1942 he was taken to a labor camp and from there to Drancy and then to Auschwitz, where he died.

Some two months later, the French police came to arrest the family and they were sent to a concentration camp in Venissieux.

At that time, attempts were being made by three organizations, the OSE (Children's Aid Society), Amitie Chretienne, and the Jewish Underground in Lyon, to remove Jewish children from the camp. Menachem and his sister were among them.

One night they took us out my sister and I [sic]. My mother remained there.

Look I don’t know anything. I have to reconstruct everything. In fact we were on our way to Auschwitz…but we were rescued. These people did far more than the average person would do. They took a grave risk. Eighty children were taken out of that camp in one night.

Transferred to Chateau de Peyrins, a private institution run by Madame Germaine Chesneau, they spent the next year and a half with 108 Jewish children. Menachem's name was changed to Marcel Faure. He has no recollection of studying there, but he does remember that they worked in the vegetable garden, celebrated only Christian holidays, and that food was scarce. One night, when Madame Chesneau noticed that one of her workers hadn't returned at night, she feared the woman had been arrested. She quickly arranged for all of the children to be dispersed to nearby villages.

Menachem Frenkel:

Until the age of nine when we immigrated to Israel, I didn’t know I was a Jew. I ate pork, like any other French boy. I wore a tie. On Sunday we would go to church. You could not wear anything, you had to be neatly dressed.

Menachem was then sent to the village of Rosans to live with the Hughes, a couple with no children. His sister was sent to a monastery.

Menachem was hidden in the attic but supplied with plenty of food and even began to study again. He remained in Rosans until the end of the war.

Menachem Frenkel:

I don’t remember if I called them father and mother. It’s hard to grasp. If you put yourself in their shoes, you have to ask yourself if you would have done the same, but the fact is that children were saved in this manner.

Madame Chesneau, the Hughes, and the priest Alexandre Glasberg of the Amitie Chretienne organization have been recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

The French Israelite Scout Movement (Eclaireurs Israelites de France, EIF)

The French Jewish scouting movement, created by Robert Gamzon in 1923, rescued thousands of Jews in France during World War II.

More than two thousand young Jews were grouped together under the auspices of twenty-six Scout groups united in the unoccupied zone, providing support for young French Scouts who were bewildered and distressed, as well as for young foreign Jewish refugees. Later, when the deportations commenced in 1942, the scouts played a major part in placing and hiding hundreds of children with French families.

Soon after war broke out in September 1939 the EIF established several children's homes in southwest France. After France fell to the German army in mid-1940, the EIF moved south to the unoccupied zone of France while still continuing to function illegally in Paris. Its children's homes soon began to take in the children of Jews imprisoned in Nazi camps, many of whom were young foreign Jews who had lost ties with society and their loved ones.

In 1941 the EIF was forced to join the Union of French Jews (UGIF), the organization established by the Vichy government to consolidate all French Jewish organizations into one unit.

When the Germans began deporting the Jews of France in March 1942, the EIF established a social service that evolved into a rescue organization, supplying Jewish children with forged identity papers, placing them in safe homes, or moving them out of France.

Many local groups also helped in the rescue of Jewish children. Catholic and Protestant church leaders, regular French citizens, and underground groups rescued children from internment camps and placed them in the safe havens of private Christian homes or in institutions. They provided the children with necessary supplies, including false identity papers. In many cases, they coordinated their activities with those of the French Scouts and the OSE.

Saul Friedlander

Saul Friedlander, today a preeminent Holocaust historian, was born in Prague into a middle-class assimilated Jewish family. As Hitler came to power, the family searched for a safe haven, eventually arriving in France. In 1942, when foreign Jews in France started to be rounded up, in an attempt to save their son, Freidlander’s parents placed him in a Catholic boarding school where, at the age of ten, he took on a new name and was baptized. He had a very difficult time adjusting to a whole new way of life and the disappearance of his parents was traumatic. He became a devout Catholic, and seriously considered becoming a priest.

“A few days later after my return to Neris, the last scene of our family life of which I have any memory took place. All three of us, my father, mother, and I were in the same room. My mother was packing a suitcase - one that I was to take with me and two or three that my parents were going to take with them…

The very day I left for La Souterraine my mother had written to Madame M. de L; “In my despair I am turning to you, for I have learned through my husband that you have taken pity on us and understood what was happening to us. We have succeeded, for the moment at least, in saving our boy…but I don’t want to leave him where he is, for today one can no longer have any confidence in a Jewish institution. I beg you, dear Madame, to agree to look after our child and assure him your protection until the end of this terrible war. I don’t know how he could best be safeguarded, but I have complete confidence in your goodness and your understanding.”

Saul Friedlander, When Memory Comes (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1979), pp. 77-78.

When the war was over and his parents didn't return, a priest talked to Friedlander about what had happened to them. It was at this point that Friedlander found out all about the war; he had no idea what Auschwitz was. He now understood the implications of his having been born a Jew and he immediately took back his real name, eventually immigrating to Israel.

Federation of Jewish Societies of France

The Federation of Jewish Societies of France (Federation des Societes Juives de France, FSJF) was an umbrella organization of Jewish immigrant societies in France, established in 1913. These societies, divided into groups according to geographical origin, were made up of Jews who had immigrated to France from Central and Eastern Europe. The FSJF existed at all points to mediate the conflict between Jewish immigrants to France and native-born French Jews, who had their own umbrella organization. By the late 1930s the FSJF included over 200 immigrant societies.

After the Germans occupied northern France in 1940, most FSJF leaders fled to unoccupied southern France. They created underground FSJF committees in many areas, which took care of tens of thousands of Jews, and provided them with forged identity papers. When the Germans invaded southern France in late 1942, the FSJF set up an absorption center in the part of France occupied by Italy, where Jews were protected from the Nazi and French authorities. The FSJF also funded Jewish youth organizations that smuggled Jewish children into Switzerland and sent young underground fighters to Palestine via Spain. In addition, the organization set up Partisan units in several French cities. In August 1942 the FSJF helped institute the Jewish Defense Committee, which encompassed all Jewish underground organizations.

Le Chambon sur Lignon 1941-1944 (The Protestant Mountain)

A Protestant community, which became a haven for Jews, many of whom were children, was situated in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and tiny villages around it. Led and initiated by pastors, they felt it their Christian duty to hide and save as many Jewish children as possible. The rescue activities that took place in Le Chambon were initiated and led by the town's pastor, Andre Trocme, and his wife Magda. The Protestants in France had known and understood persecution and many had found safety in the mountainous areas surrounding Le Chambon sur Lignon. Trocme encouraged his constituents to assist Jews who were fleeing the Nazis, by hiding them in their private homes and farms. Other Jews were given refuge in children's homes and public institutions within Le Chambon. Some were smuggled over the border into Switzerland. Volunteers from Le Chambon, such as Pastor Edouard Theis, took these Jews on dangerous journeys through French towns and villages. Upon arrival at the Swiss border, they handed the Jews over to Protestant volunteers on the other side.

Daniel Trocme, Pastor Trocme’s cousin, was the director of a children's home in Le Chambon. In that capacity, he rescued many Jewish children. However, he was arrested in June 1943 and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he perished.

After the war, Yad Vashem recognized Andre Trocme, Daniel Trocme, Edouard Theis, and thirty-two other inhabitants of Le Chambon as Righteous Among the Nations.

Approximately seven thousand Jewish children in France were saved during the Holocaust due to the courageous efforts of various groups, and brave individuals too many to mention here.

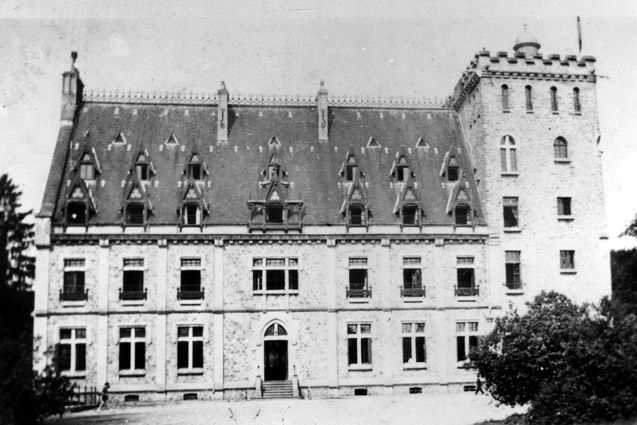

Many of the pictures that accompany this article are taken from an album of photographs of a children's home in Saint Georges, France, where Jewish children were hidden during the Holocaust. Juliette Vidal and Marinette Guy established the home in 1942. Both were later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. They converted the summer camp they ran into a children's shelter after it was discovered that many of the children who were staying at the camp had lost their parents. The OSE took over the operation and moved it to the Hotel de la Paix. Most of the staff members were Jewish and the children were allowed to preserve their Jewish identity. The submitter, Tzipora (Fela) Izbozki, was a Belgian woman born in Poland in 1923. She escaped with her family in 1940 to Southern France and was hired by Juliette Vidal as a nanny. She received the album from another nanny, Madelyn.