After Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933, the Hungarian government became interested in making an alliance with Nazi Germany. The Hungarian Government felt that such an alliance would be good for them, in that the two governments maintained similar authoritarian ideologies, and the Nazis could assist Hungary in retrieving land it had lost in World War I. Over the next five years, Hungary moved closer to Germany.

The Munich Conference of September 1938 allowed Germany to annex the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia. In November, Germany carved a piece of Czechoslovakia — territory that had formerly belonged to Hungary — and handed it back to Hungary in order to cement the relations between the two nations. In August 1940, Germany gave Hungary possession of northern Transylvania. In October 1940, Hungary joined Germany, Italy, and Japan in the Axis alliance.

Hungary was awarded more land in March 1941 when, despite its alliance with the Yugoslav government, Hungary joined its new ally, Germany, in invading and splitting up Yugoslavia. By that time, with all its new territories, the Jewish population in Greater Hungary had reached 725,007, not including about 100,000 Jews who had converted to Christianity but were still racially considered to be “Jews.” Approximately half of Hungary's Jewish population lived in Budapest, where they were very acculturated and a part of the middle class.

Hungary commenced issuing anti-Jewish legislation soon after the Anschluss in March 1938. Hungary passed a law whereby Jewish participation in the economy and the professions was cut by 80 percent. In May 1939, the Hungarian Government further limited the Jews in the economic realm and distinguished Jews as a "racial," rather than religious group. In 1939 Hungary created a new type of labor service draft, which Jewish men of military age were forced to join (see also Hungarian Labor Service System). Later, many Jewish men would die within the framework of the forced labor they performed pursuant to this draft. In 1941 the Hungarian Government passed a racial law, similar to the Nuremberg Laws, which officially defined who was to be considered Jewish.

Although these anti-Jewish laws caused many hardships, most of the Jews of Hungary lived in relative safety for much of the war. Despite this relative safety, however, tragedy struck in the summer of 1941. Some 18,000 Jews randomly designated by the Hungarian authorities as "Jewish foreign nationals" were kicked out of their homes and deported to Kamenets-Podolsk in the Ukraine, where most were murdered. In early 1942, another 1,000 Jews in the section of Hungary newly acquired from Yugoslavia were murdered by Hungarian soldiers and police in their "pursuit of Partisans.”

As the war progressed, the Hungarian authorities became more and more entrenched in their alliance with Germany. In June 1941, Hungary decided to join Germany in its war against the Soviet Union. Finally, in December 1941, Hungary joined the Axis Powers in declaring war against the United States, completely cutting itself off from any relationship with the West.

However, after Germany's defeat at Stalingrad and other battles in which Hungary lost tens of thousands of its soldiers, the Regent of Hungary, Miklos Horthy, began trying to back out of the alliance with Germany. This, of course, was not acceptable to Hitler. In March, 1944, German troops invaded Hungary, in order to keep the country loyal by force. Hitler immediately set up a new government that he thought would be faithful, with Dome Sztojay, Hungary's former ambassador to Germany, as Prime Minister.

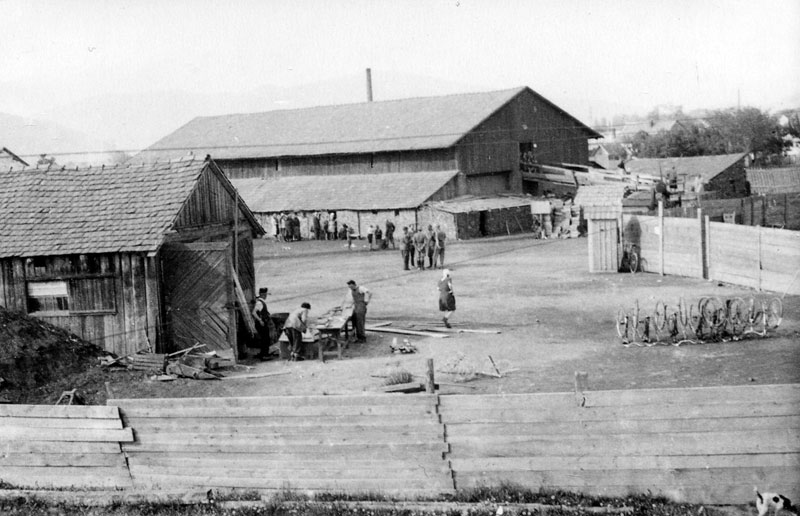

Accompanying the German occupation forces was a Sonderkommando unit headed by Adolf Eichmann, whose job was to begin implementing the “Final Solution” within Hungary. Additional anti-Jewish decrees were passed in great haste. Judenräte were established throughout Hungary, with a central Judenrat called the Zsido Tanacs established in Budapest under Samu Stern. The Nazis isolated the Jewish population from the outside world by restricting their movement and confiscating their telephones and radios. Jewish communities were forced to wear the Yellow Star. Jewish property and businesses were seized, and from mid to late April the Jews of Hungary were forced into ghettos. These ghettos were short-lived. After two to six weeks the Jews of each ghetto were put on trains and deported. Between May 15th and July 9th, about 430,000 Hungarian Jews were deported, mainly to Auschwitz, where most were gassed on arrival. In early July, Horthy halted the deportations, still intent on cutting Hungary's ties with Germany. By that time, all of Hungary was "Jew-free," except for the capital, Budapest. Throughout the spring of 1944 Israel Kasztner, Joel Brand, and other members of the Relief and Rescue Committee of Budapest began negotiating with the SS to save lives. These negotiations are discussed in greater depth below. Many Jews (perhaps up to 8,000) fled from Hungary, mostly to Romania, many with the help of Zionist youth movement members.

From July to October, 1944, the Jews of Budapest still lived in relative safety. However, on October 15 Horthy announced publicly that he was done with Hungary's alliance with Germany, and was going to make peace with the Allies. The Germans blocked this move, and simply toppled Horthy's Government, giving power to Ferenc Szalasi and his fascist, violently antisemitic Arrow Cross Party. The Arrow Cross immediately introduced a reign of terror in Budapest. Nearly 80,000 Jews were killed in Budapest itself, shot on the banks of the Danube River and then thrown into the river. Thousands of others were forced on death marches to the Austrian border. In December, during the Soviet siege of the city, 70,000 Jews were forced into a ghetto. Thousands died of cold, disease, and starvation.

During the Arrow Cross's reign of terror, tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest were saved by members of the Relief and Rescue Committee and by other Jewish activists, especially Zionist youth movement members, who forged identity documents and provided them with food. These Jews worked together with foreign diplomats such as the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg, the Swiss Carl Lutz, and others who provided many Jews with international protection.

Hungary was liberated by the Soviet army by April 1945. Up to 568,000 Hungarian Jews had perished during the Holocaust.

The Kasztner Controversy

Dr. Israel (also known as Rudolf or Rezso) Kasztner was a Hungarian Zionist leader in his native Transylvania and then in Budapest after Transylvania was annexed by Hungary in 1940. In late 1944 he helped found the Relief and Rescue Committee of Budapest. Until spring 1944, the committee successfully smuggled refugees from Poland and Slovakia into Hungary.

Once Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, Kasztner came to believe that the best way to save Hungarian Jewry – the last Jewish community in Europe – was to negotiate with the German authorities. Thus, the Rescue Committee contacted the SS officers in charge of implementing the "Final Solution" in Hungary. Soon thereafter, Adolf Eichmann made his offer to exchange "Blood for Goods," whereby a certain number of Jews would be spared in exchange for large amounts of goods, including trucks. Kasztner negotiated directly with Eichmann and later with Kurt Becher, a Nazi official.

In late June 1944, Kasztner convinced Eichmann to release some 1,700 Jews. Kasztner and other Jewish leaders drew up a list of Jews to be released, including leading wealthy Jews, Zionists, rabbis, Jews from different religious communities, and Kasztner's own family and friends. They were transported out of Hungary on what came to be known as the "Kasztner Train." After being detained in Bergen-Belsen, the members of the "Kasztner Train" eventually reached safety in Switzerland.

Kasztner and Becher continued negotiating for an end to the murder and later for the surrender of various Nazi camps to the Allies. These negotiations may have led to the order to stop the murder in Auschwitz and to stop the deportations from Budapest in fall 1944.

After the war, Kasztner moved to Palestine and became a civil servant working in the Israeli government. He was accused of collaborating with the Nazis by a journalist named Malkiel Grunwald. The Israeli government sued Grunwald on Kasztner's behalf in order to clear Kasztner's name, but Grunwald's lawyer turned the trial into an indictment of Kasztner. The judge summed up the trial by saying that Kasztner had "sold his soul to the devil" – by negotiating with the Nazis, by favoring his friends and relatives on the Kasztner Train, and by not doing enough to warn Hungarian Jews about their fate.

Kasztner appealed this verdict and, ultimately, the Israeli Supreme Court cleared Kasztner of all wrongdoing. However, before the new decision could be announced, Kasztner was assassinated by extreme right-wing nationalists.