- Anita Shapira and Irit Keynan, The Survivors of the Holocaust

- The Long Way Home, Dir. Mark Jonathan Harris, Prod. Richard Trank, Rabbi Marvin Hier. Seventh Art Releasing, 1997. Film.

- Kleiman, Yehudit and Springer-Aharoni, Nina, eds., The Anguish of Liberation (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1995), pp. 45-46.

- Ibid.

- Zurach Warhaftig, Uprooted (New York: Institute of Jewish Affairs of the American Jewish Congress and World Jewish Congress, 1946), p. 135.

- Meyer Levin (ed.), “Diary of Kibbutz Buchenwald”, Commentary Magazine, June, 1946, p. 32.

- From the testimony of Shoshana Stark, Yad Vashem Archive 03/4337, pp. 19-20 (Hebrew).

- Testimony of Rachel Ben-Chaim, Yad Vashem Archive, 03/6921, pp. 40-43 (Hebrew).

- Miriam Akavia, Return to Life, Beth Hatefutsoth, Beit Lohamei Haghetaot, Yad Vashem (Hebrew).

World War II ended in May 1945. After six years of war, there were victory celebrations all throughout the streets of Europe. For the Jewish survivors, though, the victory had been too long in coming. Entire Jewish communities in Europe had been wiped out and their Jews exterminated. For instance, the Jewish community in Poland, the largest in Europe, had been decimated: of the 3,500,000 Jews living in Poland before 1939, only 250,000 were still alive, most of them in the Soviet Union; fully 93 percent had perished.1 In all of Europe, not including the Soviet Union, where over seven million Jews had lived in thriving communities before the war, there were at the end of the war approximately 1,500,000 Jews. In Germany itself, there were about 60,000 Jews on V-E Day, most of them prisoners liberated from concentration camps, many after death marches from camps further to the east. In Poland, there were only about 70,000 Jews left. Some of these were survivors of camps, others had been hidden during the war or had masqueraded as Christians with false identity papers. Still others were surviving ghetto fighters, partisans and those who had fled to the forests.

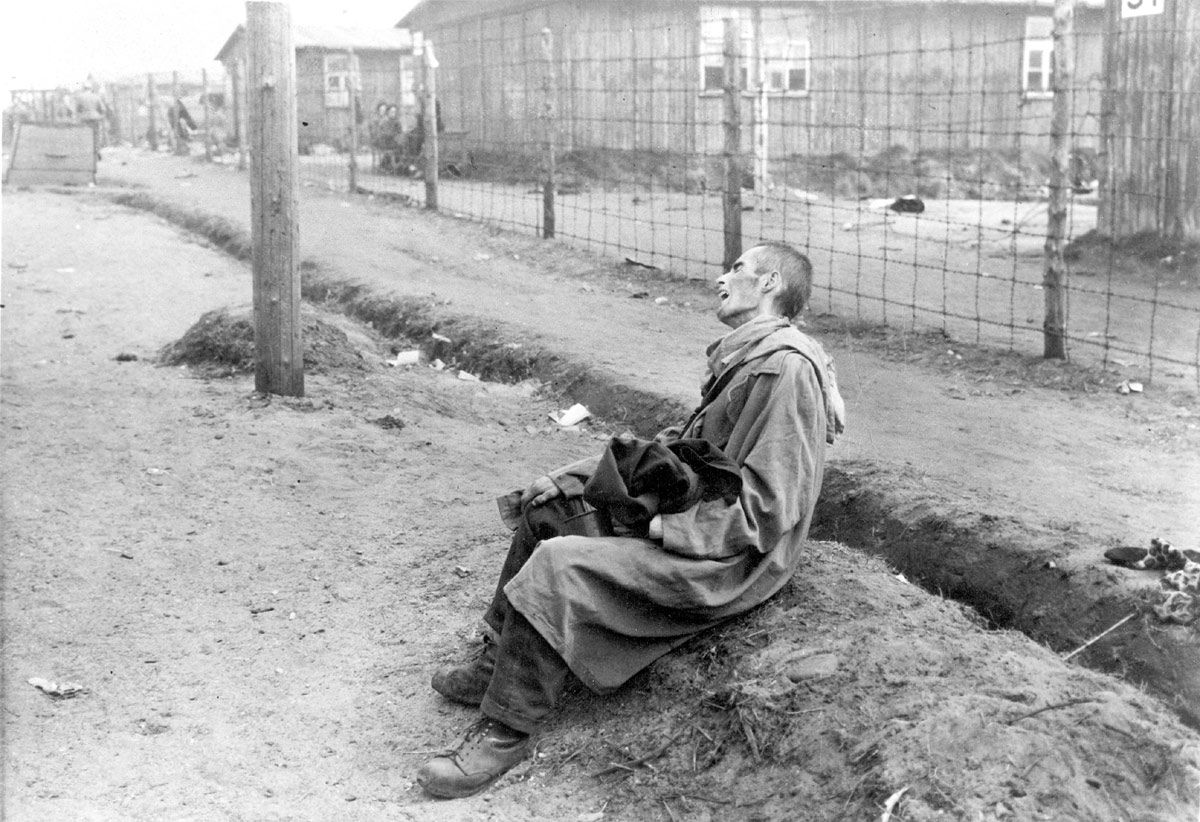

For those Jews who survived, the day of liberation was a difficult one for many reasons. Many were physically spent, or at varying degrees of physical deterioration. Many were too weak to rejoice at their liberation — they were apathetic. Mentally and emotionally, as well, the Jews were exhausted. They had been living in terror and fear for years.

"The soldiers came up to the fence and just stood there looking at us. I couldn't understand their behavior at all. I wish I could tell you how eerie that was watching them staring at us in that inexplicable way. But then I saw one of the soldiers double over and throw up, soon another was doing the same, and then another. And then I understood. They were looking at us in disgust. A deep despair came over me. I felt like Adam when he first knew he was naked, horrible and ashamed. I looked around me and saw myself and the other prisoners for the first time through the eyes of those soldiers. We were disgusting to look at, no doubt about it. It's odd, isn't it, that I had never realized that before. A moment after that first soldier threw up a strange thing happened among the prisoners. We began turning away from them. We turned our backs to them. We didn't want them to see us. And if a short while before we had in some dim kind of way wanted them to come into the camp, now very strongly we wanted them to stay where they were or else to go away."2

Toward the end of the war, camp guards had threatened prisoners that they would not be left alive to see liberation. The constant fear and terror was emotionally debilitating, as was the knowledge of those who had not survived.

With liberation came the knowledge of the immensity of the loss. An almost superhuman effort was needed to pick up the pieces of broken lives and to start over again. In many cases, whole families had been slaughtered, and only single members were left. A survey taken by the Organization for Jewish Refugees in Italy, for example, found that fully 76% of the Jewish refugees had lost all of their immediate families and all of their relatives, and were single survivors of exterminated families.

Eva Braun is a case in point. Born in 1927 in Slovakia, Eva was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and then to Reichenbach, where she was one of the millions of forced laborers exploited by the Nazis. She was liberated by the U.S. army, together with her sister, in 1945. She recalls:

“We woke up in the morning and there was absolute silence everywhere. The watchtower was empty. The SS men had disappeared. Suddenly we heard a noise from the direction of the road. [...] And then someone shouted that they were Americans. The Americans came in and liberated us. [...] All through the war we had prayed for liberation, and here it was suddenly. You are free! But after I had digested the idea of freedom I realized that actually the whole time I had been hoping to see my father, and I even dared to hope that I might possibly see my mother, in spite of everything. I knew in my heart that this was almost completely unrealistic, but I was sure I would see my father. But still, there were doubts, and I began to understand that it might not happen. When I heard about freedom, I was also very frightened. What would we find?"3

Liberation day was the first day survivors were forced to confront reality, and so it became the first day of existential crises. Up until then, survivors had expended all their efforts on the struggle to survive. All their energies were spent on scavenging for food, in protecting themselves, in living from minute to minute. The struggle to survive from one moment to the next had deflected attention from the world they had lost: their family and friends, their occupations and habits, their neighborhoods and their possessions. All of these had been taken from them long before liberation, but now they were forced to face the emptiness and try to build something new.

"We had survived, and we had to return to civilization, but how did one behave in a normal world? We were two young girls who had nothing. Who would look after us? What would we do? There was excitement, but our feelings were mixed. We were afraid. It's hard to describe and explain these feelings of simultaneous fear and joy. That was our next stage. Now, after liberation, what were we going to do? We had nothing. We were frightened that we might not have anyone left in the world. We needed someone to look after us and take care of us. And to a great extent I was looking after my little sister and another girl. More than anything else I wanted someone to look after me and relieve me of the burden of caring for the girls, so that I wouldn't have to be responsible, so that I would be under an adult's protection. It's hard to explain it, but I wanted someone to look after me, I wanted someone to lean on. It turned out that freedom is relative to a very great extent. Worry about the future weighed heavily on me. We had to build our future, but how does one build a future?”4

While the victors danced in the streets, and the vanquished gathered up the broken pieces and began to look ahead, the survivors prepared themselves for — what exactly?

Returning Home

The original plan for those displaced as a result of World War II was to repatriate them to their countries of origin as quickly as possible. The possibility that displaced persons would not want to return to their homes was unforeseen – yet, this was exactly the situation for most of the Jews. Many Jews who returned to their homes encountered virulent antisemitism. The hostility of the populace added to the feeling of tragedy. In Poland more than 1,000 Jews were killed during the first year after liberation5, while the government was too weak to prevent the carnage. The postwar pogroms were carried out not by Nazis but by the local populations in various countries. The most notorious of these pogroms occurred in the city of Kielce, Poland in July, 1946 .

If the antisemitism was not enough reason for the Jews to resist repatriation, the memories of their experiences in the war provided another cause. Many tried to return home after liberation in order to search for missing relatives or to retrieve property. Instead, they found strangers living in their houses, ruins of their communities, and reminders of families and friends they had lost.

"The Jews suddenly faced themselves. Where now? Where to? They saw that they were all different from all the other inmates of the camp. For them things were not so simple. To go back to Poland? To Hungary? And they saw visions from old times, vision of Jewish villages… a white-bearded Jew, all bloodied… little children thrown from upstairs windows into the street… masses of Jews streaming into the unknown. And now, streets empty of Jews, towns empty of Jews, a world without Jews. To wander in those lands, lonely, homeless, always with the tragedy before one’s eyes… and to meet, again, a former Gentile neighbor who would open his eyes wide, and smile, remarking with double meaning, 'What! Yankel! You’re still alive!' For us, there was no going back where we came from."6

Repatriation was not a solution for the Jewish survivors. In a poll taken by the Organization of Jewish Refugees in Italy in February, 1946, of over 9,000 displaced persons interviewed, only one expressed a desire to return to his country. Of 51,000 Jews repatriated to Hungary in May and June of 1945, 41,000 had left within a few months for displaced persons camps in other countries.

Shoshana Stark was born in Kosice, Slovakia. She was deported to Auschwitz in 1943, where she was sent to the Plaszow labor camp and from there, to other labor camps. She survived a death march to Bergen-Belsen and was liberated there by the British. In 1946 she was taken to Sweden by the Red Cross – from there she returned to her town.

“I went home. I didn’t have anywhere I could stay... The gatekeeper was living in the house and wouldn’t let me go in... I also had aunts and family. I went to see all their apartments. There were goyim [gentiles] living in every one. They wouldn’t let me in. In one place, one of them said, ‘What did you come back for? They took you away to kill you, so why did you have to come back?’ I decided: I’m not staying here, I’m going.”7

Jews who had attempted to go back to their homes, especially those from Eastern Europe, soon found themselves turned back around and headed west, back towards the Displaced Persons ("DP") camps in western Europe and, ironically, back to Germany.

Immigration

In many cases, the hope of discovering someone alive was quickly extinguished. The majority of Holocaust survivors found themselves without family, homes and communities. Antisemitic incidents undermined any hope of continued Jewish existence in Eastern Europe. Many Jewish survivors believed that they had to leave Europe which had, to them, become a vast cemetery of the Jewish people.

The doors of the United States, Canada and the rest of the countries of the West remained closed to the refugees for quite some time, despite humanitarian and political efforts to the contrary (only 12,000 Jewish refugees succeeded in immigrating to the United States before 1948). Thus, Israel became the preferred destination for the displaced Jews. Earl Harrison had recognized that DPs overwhelmingly wanted to go to Palestine (the future state of Israel) in his report in August 1945. In a subsequent poll of 19,000 Jewish DPs, 97% named Palestine as their preferred destination. Asked to pick a second choice, many of them wrote “crematorium.”

The movement of the Jewish survivors out of Europe and towards then-Palestine was called the “bericha”, Hebrew for “escape.”

The bericha started as the spontaneous reaction of activist groups amongst many of the survivors. The leaders of the bericha movement included Abba Kovner and a group of surviving fighters from the Vilna Ghetto, as well as a group of Jewish partisans led by the Lidovsky brothers, who had hidden in the forests around Rovno, in Volhynia. These leaders tried to assist the Jewish refugees. In the beginning they helped the first survivors steal illegally across the borders. They organized journeys for fellow Jews, provided forged Red Cross documents, guided the Jewish refugees through mountain passes to unpatrolled borders and helped them bribe soldiers at checkpoints. All of this was done in a very haphazard fashion. With the passage of time, a more organized system of bericha evolved.

The roots of the bericha movement were in Zionism, and Zionist youth movements. The Zionist movement had been founded in 1897, almost forty years before the Nazis came to power in Germany, at a time when Jews were being persecuted throughout Eastern Europe. The movement’s founders believed that it was essential for the Jews to establish a homeland, and that this homeland should be in the Biblical Land of Israel. In the prewar period, members of Zionist youth groups had aided Jews in escaping from German-occupied territories to Palestine. Now, in the post-war period, the aim of those youth group members who had survived, some in the uprisings and armed resistance in the ghettos of Europe and others as partisans, was to bring as many survivors as possible to Palestine out of a sense of Zionism, as well as a sense that this movement would decide the fate of the Jewish people.

After the Kielce pogrom, the bericha movement changed abruptly. The thin stream of refugees became a heavy current – and it also became semi-legal. In the wake of the pogrom, a secret agreement was reached with Poland: in view of the authorities’ inability to cope with antisemitism and to ensure the safety of the Jews, they deemed it preferable to solve the “Jewish Problem” by giving Jews the semi-legal possibility of emigration. This arrangement remained in effect until February 22, 1947, when the border was closed. In the interim, over 100,000 Jews were able to flee Poland.

Illegal immigration was difficult and dangerous. Border crossings involved the danger of being sent back to the country from which the refugees had fled, or making their way over the mountains through rough territory. This fact did not deter families, even those with small infants. Conditions aboard the ships bound for the Land of Israel were very difficult. The refugees slept in crowded bunks, one on top of the other. Sanitary facilities were sorely limited; food and water were lacking. Still, the DPs fought for the right to board the ships that would take them to Palestine – ships that often were not seaworthy. All told, approximately 530,000 immigrants entered Palestine before the State of Israel was established; one-quarter of that number entered illegally, by way of Aliya Bet.

Rachel Ben-Chaim’s story illustrates the entire desperate journey of the Jewish refugees. She was born in Hungary in 1926. During WWII she was imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau and the Stutthof camp. Rachel survived a death march, and in January 1945 she was liberated by Russian soldiers. Rachel immigrated to Palestine in January 1946. She recalled:

"We crossed the borders using several strategies, at least four or five borders. Twice we were given forged papers... We crossed one border on foot. I was carrying someone's child. We crossed another border in a goods train. [...] Later we reached Villa Emma in Italy, and we were there for a long time without doing much. We left there later, and this is how it was: they loaded us onto lorries and tied down the tarpaulins over us. The [Jewish] Brigade soldiers, who belonged to the British Army, closed off the road, saying that only the army could go through, and we were the 'army'. They took us to the harbor... they almost threw us [onto the ship], because it was all very urgent. We had to get into the ship's hold very quickly, more than nine hundred of us. They just poured us into the ship... When the ship anchored off the coast of Palestine the English discovered us. Warships surrounded us and then something happened that I shall never forget, even though 47 years have gone by since then. We dropped anchor in the middle of the sea, we hoisted the national flag to the top of the mast, and we felt that the entire Jewish people was standing on the Haifa shore, because the deck was full... you don't forget something like that, it gave us the strength to endure many difficulties."8

At the beginning of 1946, the British tightened their control of the waterways, staging a naval blockade off the coast of Palestine. British destroyers with sophisticated equipment sat in the harbor and intercepted ship after ship of refugees. They were brought to the port of Haifa or, after the autumn of 1946, to Cyprus. In Haifa and on Cyprus, the refugees were once again placed in detention camps behind armed guard and barbed wire. More than once, boarding parties intercepting the “illegal” ships fired on and killed refugees crowded together on their decks.

However, Great Britain could not hold out against the determination and tenacity of the survivors. In July, 1947,4,500 Jewish illegal immigrants, all Holocaust survivors, sailed from France on a ship called the "Exodus 1947." The Exodus was intercepted near the coast of Palestine. The refugees were forced to return in three British ships to France, but they refused to disembark. They called a hunger strike to attract worldwide publicity. The British sent the ships to Germany, planning to intern the Jews in former Nazi concentration camps in the British zone of occupation. When the British, lacking sensitivity to the plight of the survivors, used clubs and high-power hoses to force the Jewish refugees off the boat in Hamburg, the entire civilized world was shocked by the incredible scene of Jews being beaten by those who had so recently won the war against Hitler. The Jews were, again, back in the country where the Holocaust had begun. The Exodus affair was a major public relations disaster for Great Britain.

Absorption into their New Countries

On August 31, 1947, soon after the "Exodus" incident, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended that Great Britain relinquish control of the area granted by the League of Nations in 1922, and that this area be partitioned into two states: one Arab and one Jewish. This was authorized by the UN General Assembly on November 29, 1947. At this time there were still 250,000 displaced persons in the refugee camps of Germany and Austria, two-thirds of whom were Polish Jews. Ultimately, a Jewish state in Israel was established on May 14, 1948. Once the door was flung open for immigration, about two-thirds of the 250,000 survivors remaining in Europe chose to immigrate to Israel, despite the hardships. Among these hardships was the fact that the fledgling State of Israel was engaged in a war for its survival, initiated by all of the surrounding Arab countries. After the establishment of Israel, some ten thousand DPs took part in the War of Independence, and many gave their lives in defense of their new homeland.

One-third of the remaining survivors chose to reconstruct their lives in Western Europe, North or South America, Australia and South Africa. In 1948, changes were made in the immigration regulations of Canada and the United States, enabling a large part of the survivors to find refuge in these countries. Within a few years’ time, the DPs were absorbed and integrated into the countries in which they settled.

The Holocaust left its scars on the survivors. In many cases, their return to life after the Holocaust was laden with anguish as well. The story of liberation should have been a happy ending to a tragic story, but it, too, had elements of tragedy. The Jews were liberated, but not free. The story of liberation and the return to life was only the beginning of a much longer struggle.

"Our daughter was born seven years after we were married. She brought much joy into our lives. […] All of a sudden, I saw my mother's eyes. The next day, I saw that she looked like my father. So I realized that despite it all, there is continuation."9