Introduction

IntroductionCommon perceptions of the Shtetl have, to a great extent, been influenced by different art forms, ranging from works of fiction by Isaac Bashevis Singer, through Marc Chagall’s paintings of figures floating over his hometown of Vitebsk, to clips and songs from Fiddler on the Roof, a musical based on Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman.

In recent years however scholars have been preoccupied in defining the dichotomy between the Shtetl as a fictional image and the Shtetl as a historical reality.

In an attempt to give our own take on this subject, we will examine the fine line between fiction and reality of the Shtetl, by juxtaposing photographs taken by Solomon Iudovin, an artist and photographer of Jewish descent, with works by modernist Jewish artists: Meer Akselrod, Issachar Ber Ryback, Regina Mundlak, and Grigory Inger, depicting different aspects of life in the Shtetlekh: the market, professions, women of the Shtetl, and Jewish learning. Through a dialogue between the two media depicting similar (visual) narratives and subject matters, we will explore the Shtetl as seen through the eyes of these Jewish artists looking to gain deeper understanding of its complex and dynamic nature.

Our topic raises two complex questions. First, what is the Shtetl? Second, who is a Jewish artist?

So indeed, what is the Shtetl (plural: Shtetlekh)? Was it an isolated, run down Jewish settlement stricken by poverty and replete with pogroms, or a thriving Jewish community as vibrant as in any large city in Europe? Was it an entirely Jewish world with few interactions with gentile neighbors? How do we grasp the reality of each Shtetl, since each one had its own history and traditions and was a separate little world with its unique architecture, dwellers, and customs?

Answering the question of who is a Jewish artist and what is Jewish art, especially in the modern period, is no less difficult to define. Questions about whether there is Jewish art and what that art is, are part of an ongoing scholarly debate. The interplay between secular and Jewish identities in works of artists of Jewish descent has led scholars to debate whether all Jews who are artists produce Jewish art or only those who in their art stress their Jewish identity.

In addition, the two subjects are connected, as the Shtetl is not only significant for understanding Jewish culture and tradition, but also for understanding Jewish art, as many influential Jewish artists were born and grew up in the Shtetlekh. Therefore, it is only natural to take the Shtetl as a point of departure when studying Jewish art.

The artworks presented in this article were created by lesser-known artists. Our goal was to present as extensive and diverse palette of artistic conceptions of the Shtetl as possible through a selection of artists with different aesthetics and styles.

A comparison between the documentation photography and artworks offers us an insight into the nuanced character of the Shtetl; how it really was and how was it shaped in the collective memory of the Jewish people. Hopefully, the presented visual material and discussions will pull the readers into a unique, personal experience of the Shtetlekh that will break away from generalizations and romanticized nostalgia. Therefore, by juxtaposing photographic images with representation of the Shtetl in arts, we will hopefully acquire better understanding of reality vs fantasy and imagination.

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that both photography and artworks are subjective forms of expression showing the world as the artist himself or herself sees it. While most works of fine arts are naturally regarded as highly subjective, photography is often perceived as presenting an objective image of reality. However, photography too is driven by subjective factors and personal creative decisions. Understood in this way, the objective/subjective distinction becomes relative and not absolute.

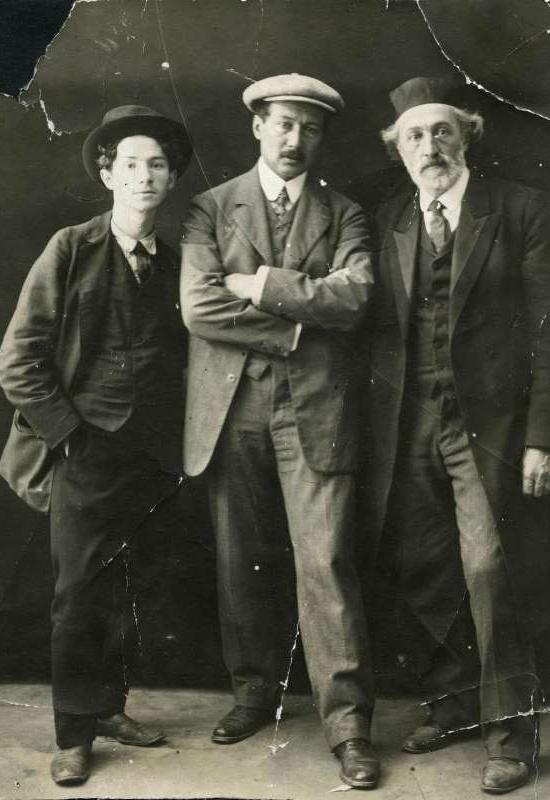

An-sky’s ethnographic expedition

An-sky’s ethnographic expeditionThe photographs by were taken during ethnographic expedition organized by S. An-sky, author, playwright, and researcher of Jewish folklore. Shloyme Zaynvl Rappoport (1863–1920), known by his pen name S. An-sky and best remembered as the author of The Dybbuk, came up in 1909 with an initiative for ethnographic expedition to record Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement. The Jewish Society for History and Ethnography assisted him on this project to conduct this research.

Altogether, in the period from 1912 to 1914, An-sky and his team conducted three expedition to over seventy towns and Shtetlekh in South-Western Ukraine (Volyń, Podillja, and Kyiv provinces). They collected over 1,800 Jewish folk tales and 1,500 folk songs, 300 objects of religious and cultural significance and took 500 wax cylinder recordings and 2,000 photographs.

Their interest was scientific - to document and in that way preserve the vanishing and changing world of the Shtetlekh. An-sky argued that the Jewish people can preserve their present and future identities only in reference to their own history and tradition. Therefore, according to him, the modern urban Jewry of the Russian Empire would be able to create a new secular Jewish culture only when based on their memory of the structures that governed the lives of the Shtetl Jews. Thus the expedition came about - out of a need to urgently document a world that would soon change irrevocably due to external influences. To join him on this expedition he recruited composer Iulii Engel, ethnomusicologist Zinoviy Kiselgof, and artist and photographer Solomon Iudovin.

During the expedition, Iudovin documented in photographs and sketches “anthropological types”, historical places, extraordinary buildings, living conditions and everyday activities – trade, craftsmanship, as well as educational and religious spheres, providing a unique insight into the everyday life of the Shtetl.

Market

MarketAt the center of the Shtetl, was a large open area, the marketplace. This was the economic hub and the pulse of the Shtetl. In addition to the market, houses of prayer – synagogues and churches, dominated the landscape. The Shtetl was often a poor place with wooden buildings and just a few brick houses, so fires were common and usually devastating. Its unpaved alleys would frequently turn into mud. Sanitary and living conditions were generally inadequate. The Shtetl was to a great extent defined by networks of economic and social relationships between Jews and non-Jews which developed and took place in the market.

A photograph by Iudovin features one such marketplace. Despite a large puddle in the foreground that draws our attention, we can grasp the centrality of the market and a typical liveliness of the Shtetl on a market day, with vendors and buyers selling and buying goods from horse-drawn wagons. The people depicted are both old and young, men and women, Jewish and non-Jewish, showing the core nature of the market, as the place of interaction between different communities.

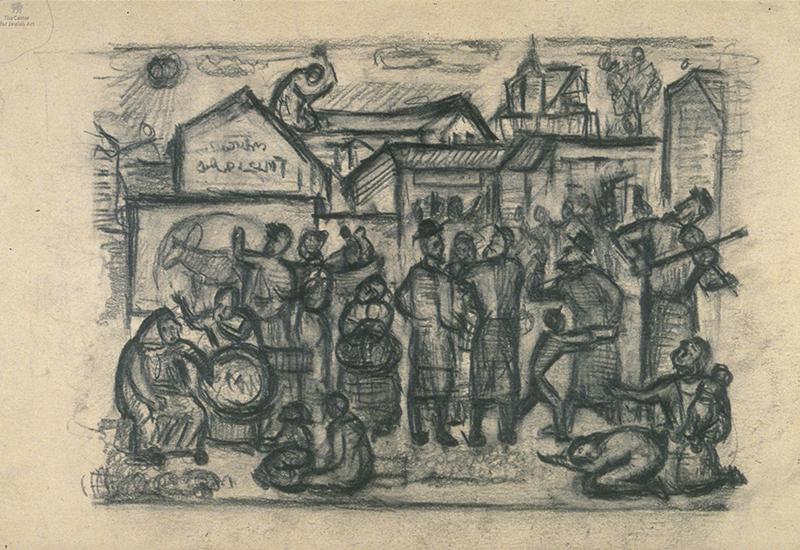

A drawing by depicts a slightly different Shtetl market. The background features the architectural landscape of the Shtetl – with residential houses, synagogues, and churches, however without real perspective, almost flat. On one of the gabled roofs one can see a chimneysweep. The market is depicted in the foreground, with a plethora of different characters. On the left-hand side, a woman leaning on a sack of goods, behind her a man with risen hands as if he is complaining to her, then a seller weighting his merchandise and a woman standing by his side. Towards the middle section, there is a woman holding a basket and in front of her two girls are seated on the ground. Behind this group a horse cart with two passengers. In the center there is a group of three men dressed in kaftans talking. To their right, a barrow boy or perhaps a thief, that either carries something in his hands stretched forward, or is trying to reach the pocket of the man standing next to him, who seems to be distracted by the conversation between the three men next to him. On the right-hand side is a tall violinist and two kneeling women, one of them with a child, who are beggars.

Compared to Iudovin’s photograph that shows us the Shtetl market as a place of hard-work, in the drawing by Akselrod the figures seem like capricious actors on the stage and the entire image seems a replica of reality, like a mise-en-scène from the theater.

Professions

ProfessionsThe Shtetl was characterized by occupational diversity: from wealthy contractors and entrepreneurs, to shopkeepers, market-traders, carpenters, cobblers, tailors, and water carriers among many others. In some regions, Jews also worked as farmers. This striking diversity on the one hand contributed to the vitality of the Shtetl but on the other hand led to painful class and social divisions. Although religion guided daily life, it was not the sole occupation of Jewish men and the scholarly class was a small, elite segment of society. Most Shtetl men worked to support their families, usually in commercial or artisanal trades.

One of the typical “Shtetl profession” was shoemaking. In Iudovin’s photograph of a cobbler, there is a striking pictorial quality of the image that seems to be emanating from the interplay of blurred and sharp contours. Our focus is on the cobbler, but he does not pay attention to us (or the photographer) as he is absorbed in his own world. Scattered tools and shoes tell us that he is the middle of work; a person behind him, who is looking directly into our/photographer’s eyes could be a customer patiently waiting for his pair of shoes to be repaired. Even though we cannot tell if the client is Jewish or Gentile, there is definitely a sharp contrast between a traditional cobbler wearing a modest clothing and a typical kasket and the client – dressed in the modern clothes of the time, wearing a fashionable hat and leaning on a cane, peacefully smoking a cigarette.

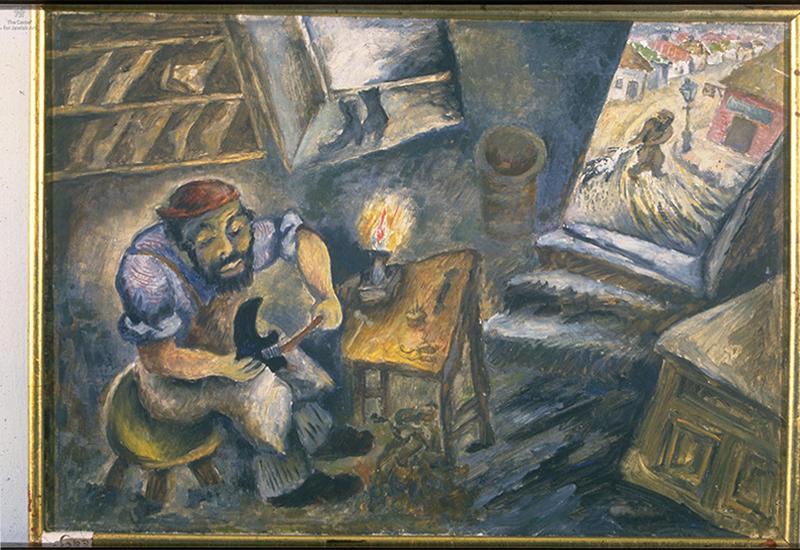

It is interesting to compare Iudovin’s photographic image of cobbler with a modernist painting by depicting the same subject-matter. Ryback’s cobbler is set in a cubist shaped environment, with simplified shapes and a broken perspective. The cobbler is depicted seated on a low stool by his worktable, fixing a shoe. He has a short black beard; his head is covered with a red skull cap. Through an open door, we can see an empty street of the Shtetl, with a line of almost identical small houses and a lonely image of a Jew “struggling” with a goat. This street scene with the bearded man and a goat is somewhat mysterious – at first glance it looks like the man is trying to pull the goat, but at a second glance, it appears as if the goat grabbed the fringes of the man’s tallit, who is in turn trying to pull them out of the goat’s mouth.

Like Iudovin’s photograph, the cobbler in Ryback’s painting also seems immersed in his work, judging by the contemplative expression on his face. However, there are no scattered tools, no customers waiting, therefore it seems that the cobbler is daydreaming, his thoughts elsewhere. The motif of the goat could designate a korban, an animal sacrifice, symbolizing according to some researchers an ill-treatment of Jews in the Russian Empire.

Women of the Shtetl

Women of the ShtetlThe women were responsible for family life, which included not only the care of children and the household and observance of religious life at home but also the financial survival. Men held the positions of power, they controlled the kehilah and, of course, the synagogue. However, behind the scene, women often played key roles in the communal and economic life of the Shtetl.

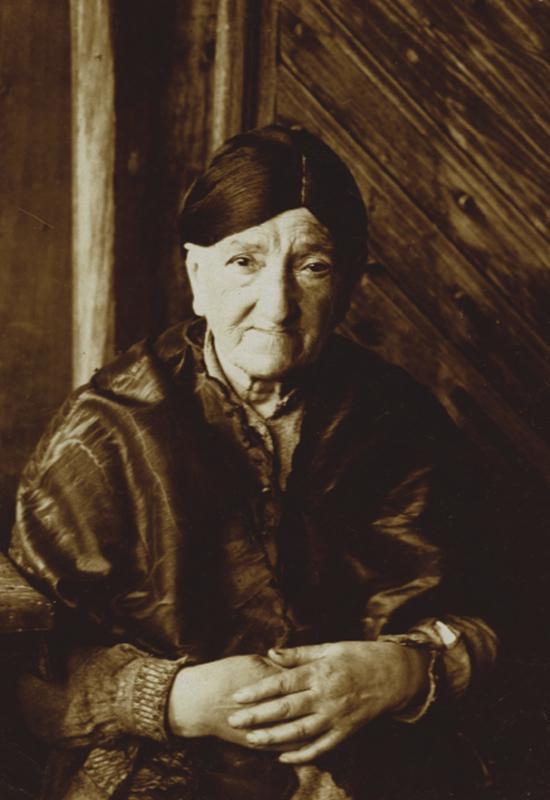

In the photograph, we see a beautiful portrait of an elderly Jewish woman. The fineness of her skin and soft silky texture of her clothes, stand in a sharp contrast with the wooden texture of the background, creating a feeling of warmth and coziness and the security of home. The image seems nostalgic, depicting the archetypical Shtetl matriarch– confident and strong.

depicted her grandmother in a similar manner. The artist presented her wearing elegant clothes with an elaborate shterntikhl, a traditional head covering worn by married Jewish women, and a cane in her right hand. Mundlak depicted realistically deep wrinkles, her large nose, and sagging facial skin of her grandmother, without any pathos or aim to beautify her model. There is a sense of nostalgia in this work – the artist already belonged to the new generation of women, who would go out into the world and leave the narrow borders of their Shtetl.

The expression of the woman in the photograph by Iudovin bespeaks of her self-esteem and confidence. Similar to that, the entire posture of the figure depicted by Mundlak suggests a strong-minded woman. The two images show the proud and self-reliant women of the Shtetl.

Jewish Learning

Jewish LearningIn the Shtetlekh, religious training was considered of paramount importance. Boys would study in a cheder, a traditional elementary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language. The children of well-to-do parents were usually taught at home by a private tutor. Besides the chederim, there was also a Talmud Torah, a communal school for the education of poor and orphan children. The ambitious students who wished to adopt the career of a Rabbi, continued their studies in a Talmudic college or Yeshiva. There would often also be separate elementary schools for girls. In some Shtetlekh there were also “progressive chederim” for children of both sexes with instruction in Hebrew.

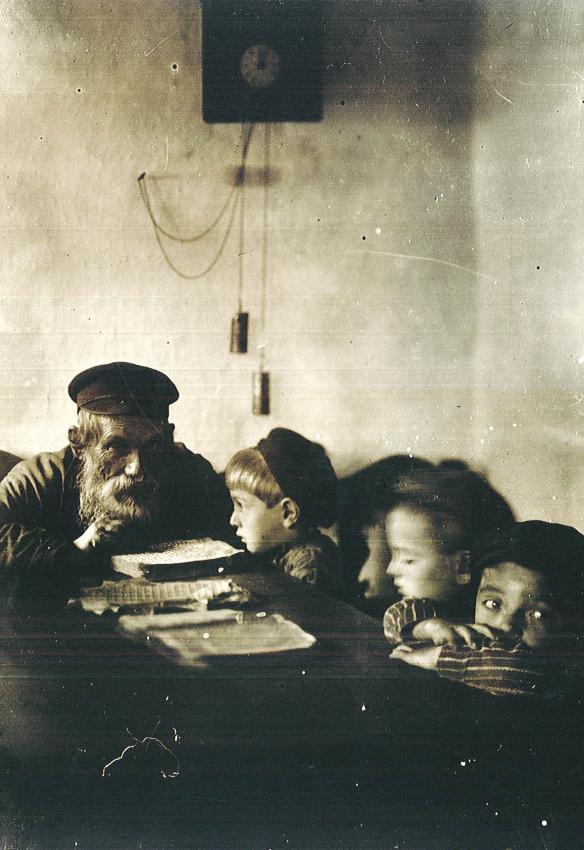

In Iudovin’s photograph, we see a cheder teacher with a group of small boys, some immersed in learning, some seemingly participating, while the boy in the foreground is completely detached from the scene, looking directly at the camera, bored or with different thoughts flying around his mind.

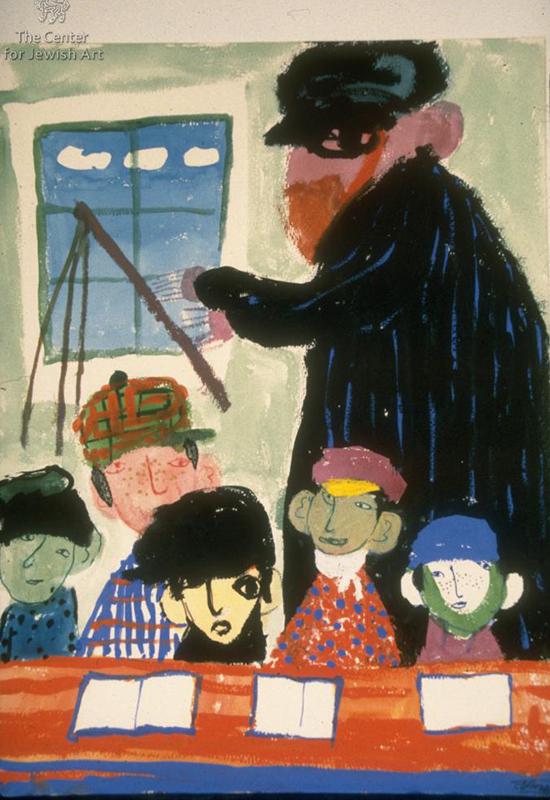

In a painting depicting a cheder in the Shtetl by , we can also see a teacher and his young students. The images are distorted, childishly naïve, almost in a poetic sense, with cheerful warm color hues. The visual language reveals the artist’s experience with the Russian avant-garde art and Primitivism. The figure of the teacher, disproportionate to the size of the room, seems to reveal the artist’s attempt to paint a child’s viewpoint or a childhood experience of learning in a cheder. The painting exposes us to the world of Jewish learning with such honesty, seen through childlike and trusting eyes, so bright colors and distorted images do not seem unnatural, on the contrary; they intensify and sharpen the reality.

Inger’s painting of the cheder is on the verge of looking foolish, but behind the grotesque and comical features of the teacher and students alike, it expresses a special, deep bond with the tradition of learning, so deeply rooted in Jewish life. Iudovin’s photograph on the other hand shows us different types of students, some immersed completely in their studies, and some intrigued by the camera, which perhaps we can see here as a metaphor for new and exciting outside world.

Conclusion

ConclusionWhether idealized or presented through historical data, the Shtetl was the heart of Eastern European Jewry and the birthplace of a rich Yiddish literature and culture. Jewish life in Europe was forever altered by the Holocaust. The Shtetlekh no longer exist, but they will continue to be researched by scholars and remembered in works of literature and arts.

The artists whose works we presented here were influenced by S. An-sky’s idea that the creation of a modern, emancipated, renewed, and secular Jewish identity will be possible only by turning back to the heritage of the Shtetl and its folk culture. They welcomed this secular identity and at the same time felt close to the roots and a visual heritage of their people. When those artists moved from their Shtetlekh to larger centers such as Kyiv, Saint Petersburg, Moscow, or even further away– to Berlin and Paris, they absorbed the avant-garde styles of the period, like the Russian avant-garde, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism, which all claimed the aesthetic power of folk and tribal art. The artists thus developed their unique styles featuring Jewish themes through a mix of folk art with elements of different styles of modern art. In addition, it seems that the artists were motivated by a sense of nostalgia similar to An-sky’s, understanding the importance of memorializing the traditional Jewish life that was slowly disappearing and would eventually be destroyed completely.

The environment of the Shtetlekh from which most of our artists come from was in many ways specific, also in regards to arts. Jewish tradition condemned the artistic trade, regarding it as a violation of the second commandment “Thou shalt not make unto thyself any graven image”.

The artists painted their villages and townships, alleys, different types and scenes depicting the life of the Jewish population of the Shtetlekh. They conducted their own artistic searches, influenced by European avant-garde movements, and some of them became world-class artists. Most artists did not illustrate his or her vision of the world of the Shtetlekh, but rather memories of their childhood. At the same time Iudovin’s depictions of the Shtetl are slightly different, due to his art medium of photography, but also due to the sense of urgency that guided him in his works, to document as much as possible of this rich, vanishing world.

Photographs and artworks are important, both as a documentation of the vanished communities as well as for their intrinsic artistic values. Regardless whether the artworks allude to the state of reality or the imagination, they offer a unique insight that draws us, the viewers, right into the complex world of the Shtetl, featuring Jewish history and heritage and evoking the rupture caused by the Holocaust.