Three Quotes: A Philosophical Note on the Title

We preface the following essay on solidarity during the Holocaust with the three quotes below in order to highlight the stark contrast between the extreme difficulties of survival and the historical examples of fortitude that follow.

- Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (London: Abacus, 1969), pp. 23-24.

- Imre Kertesz, Fateless (Illinois: Northwestern, 1996), pp.125-126.

- These committees are also known as "building committees."

- David Ben-Shalom, "Building Committees in the Warsaw Ghetto," Legacy 1:3 (Winter, 1998): 28.

- Zivia Lubetkin, In The Days of Destruction and Revolt (Israel: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1981), p.277.

- Bela Guterman, "They Will Not Destroy the Spark of Humanity in Our Hearts: Mutual Assistance and Cultural Activities in a Women's Labor Camp in the Sudetenland," Bashvil Hazikron 8 (March, 2011): 12-21 (Hebrew).

- Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (London: Abacus, 1989), p.61.

Roman Frister survived Auschwitz. In testimony that he gives in a video which appears every half hour on a screen in the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum, he states:

“The camp was like a jungle. There is no morality in a jungle. The bigger animals devour the smaller animals and these devour those even smaller. I was determined to survive…”

Primo Levi also survived Auschwitz and in the last book that he wrote, The Drowned and the Saved, he stated the following:

“One entered (the lager) hoping at least for the solidarity of one’s companions in misfortune, but the hoped-for allies, except in special cases, were not there: there were instead a thousand sealed-off monads, and in between them a desperate hidden and continuous struggle.”1

And Imre Kertesz, ten years younger than Primo Levi when they were both experiencing the pain of Auschwitz, wrote in his book Fateless: “

Certain things, that I had previously considered tremendously important… now lost all value in my eyes… Cold, wetness, wind or rain no longer disturbed me. They couldn’t reach me. I never felt them. Even my hunger vanished.”2

He goes on to write that only one thing was strengthened in him and that was his irritability.

The following essay on solidarity during the Holocaust reflects the impossibility of survival juxtaposed with examples of bravery and courage in maintaining an element of solidarity.

Introduction

The narrative of the Holocaust contains within it so many parameters of knowledge with such a vast array of facts that any study of the period is bound to be selective. The overall theme of this e-newsletter is the individual and the community and various avenues of thought open up on this subject.

Six million Jews murdered in Europe during the Holocaust was the vast majority of European Jewry, which numbered somewhere between eight and nine million. An understandable impulse is to simplify the subject and state outright that as individuals, or small family groupings, or whole communities large and small, people were marched off or loaded onto trains and herded to their deaths. This formulation leaves a reader with an indistinct understanding of death being meted out to individuals in a dark alley, to families shot into the shooting pits of Soviet Russia, and to trainloads of thousands forced into the gas-chambers of six death camps all built in Poland. This multiple death route is not an aid in penetrating the texture of the life and suffering imposed on millions in Europe during the war. And yet dehumanization and death were the major features of the Holocaust and one of the major features of the Second World War. To counter this predominance, this article will focus on the human behavior of individuals and communities and the interaction between groups and leaders in an attempt to offset the preoccupation with murder and death.

If the Holocaust is to be viewed through the prism of interaction between the individual and the community, any number of contexts suggest themselves;

- The Youth Movements and their youth counselors (madrichim)

- Religious communities and their Rabbis

- Resistance and the various groups involved

- Committees of Social Help in the ghettos

- The Righteous among the Nations

- Communal Prisoner Endeavors in the Camps

- The Extended Family Network

Some of the above examples will be dealt with in this article. The varying contexts dealt with below, in which the human spirit defied the dehumanizing nature of Nazism, are a clear testimony to the strength of this human spirit, even in extreme adversity.

Committees of Social Help in the Ghetto

The first context in which we discuss the interaction between individuals and the community is the city of Warsaw. If we return to the reality of the Jewish community in Warsaw before and after the ghetto was set up and finally enclosed in November, 1940, it is possible to trace the endeavors of socially–minded individuals who formed house committees3 to help initially with the worsening economic situation of Polish Jewry in the years before the war. Governmental measures in the 1930s had precipitated a gradual strangulation of economic life in many Jewish communities across the board and one can read about a serious deterioration of the material circumstances of many of Warsaw’s Jews during this period. Women’s circles were formed in many of Warsaw’s apartment complexes in an attempt to cope with the grave material needs of many destitute families and all this before the added difficulties of wartime.

- 3. 3

Clothing was collected for distribution and a great effort was invested in fund-raising from within all strata of the Jewish communities in a sustained effort to ameliorate the living conditions of so many families needing social assistance. The organizational network of these house committees before the war indicates a wide infrastructure of social activism that would prove invaluable during the ghetto period in alleviating some of the misery inflicted by the Germans on the biggest of all the ghettos created by them.

The war started on September 1, 1939, and the ghetto of Warsaw was enclosed thirteen months later, in November of the following year. The house committees at the outset of the war helped with the new exigencies of aerial bombardments like extending aid to the wounded and helping with blackout requirements. The major concern which developed very soon was the procurement of food supplies for the thousands affected by the disruptions of normal life.

The phenomenon of these individuals working for the common good by extending a helping hand in such extreme circumstances is occasion for a massive tribute to the human spirit. The fact is that as conditions deteriorated with the passage of time from 1940 and until the final destruction of the ghetto in May, 1943, most committees remained operating for less than twelve months. Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum organized a group of historians and academics from different disciplines to help collect, collate and write documents about life in the Warsaw ghetto under the German occupation. This archive, known as the Oneg Shabbat, is the source of rich information about these committees. Among these documents recovered after the war are heartwarming descriptions of how dedicated individuals expended so much energy in helping others. For instance, reports of the house committee at 24 Leszno Street show weekly meetings and subcommittees that were concerned with specific matters like women's groups for special duties, organizing events and artistic programs, and fundraising for children's activities.4

The Ringelblum Archives in themselves are another example of how a small group of individuals worked together in trying circumstances to preserve a reliable historical account of how such a large Jewish community lived, suffered, and ultimately died during the Holocaust.

- 4. 4

The Youth Movements

The phenomenon of the Jewish youth movements in the Holocaust is indeed worthy of the term "phenomenon" because of the dissonance that exists a priori between the aims and raison d’etre of these youth organizations and the functions they adopted and fulfilled during the years of the war.

Youth movements are traditionally organizations of young people who are involved in questioning the mores of the surrounding society and of their own families and, as such, can often be found in opposition to adult society and indeed their own parents.

When the ghettos were formed, mainly in eastern Europe, the Germans enforced their orders through the Jewish Councils, Judenraete, which had been established earlier. Thus, the internal life of the ghetto inhabitants was largely controlled according to the dictate of the Germans. This situation created fertile ground for serious clashes between the youth movements and the authority of the Jewish Councils to the point where in certain ghettos, a young leadership from these movements actually replaced the older, more conservative Judenrat. This happened in the largest of all the ghettos, Warsaw, some time before the outbreak of the famous Warsaw ghetto uprising under the leadership of resistance organizations formed by the youth movements in April, 1943. In many of the ghettos until the mass murder commenced, there had been varying degrees of cooperation between the Judenraete and the youth movement leadership.

How are we to understand this episode of a young leadership leading a revolt for more than three weeks against the German army in terms of the title of this article, The Individual and the Community?

One way of providing an answer is to point out that in another ghetto in the northern reaches of Lithuania, Vilna, the youth movements did not have the support of the adult community and thus were unable to foment a rebellion against the Germans. Thus, in Vilna, an alternative route of opposition was adopted by the youth movements who escaped the ghetto in order to fight the Germans as partisans in the forests.

The situation in Warsaw was different. In January, 1943, the Jewish youth prevented the Germans from rounding up the Jews by using armed resistance. The Germans retreated and the ghetto enjoyed a period of quiet while the Germans took stock of this new display of armed resistance. The population of the ghetto interpreted this as a positive development and the youth movement leadership was able to capitalize on the rising wave of general support for their strong-arm policy of resisting. Thus, in contrast to Vilna, the youth movements in Warsaw did enjoy the acquiescence or outright support of the majority of the approximately 50,000 Jews still alive in the ghetto and were thus able, with the collaboration of the ghetto community, to fight the German units for three weeks, beginning April 19, 1943, before they finally succumbed to the superior numbers, weapons and military strength of the Germans. The uprising was a unique episode of young people from various youth movements – the commander of the rebellion, Mordechai Anielewicz, was twenty-four years old at the time he was killed. The fact that they prevented a Wehrmacht fighting unit from implementing its murderous design for so long is a clear-cut example of individuals acting on behalf of the wider community, together with its cooperation, to achieve a joint aim. Whether the fighters lived or died at the end of the uprising is irrelevant in terms of the subject at hand; the fact that such unprecedented civilian opposition to German operations could be mounted at all is of the utmost relevancy in terms of the cooperative forces at work in the community.

Thus, the Warsaw ghetto uprising is a testimony both to the organizational ability and drive of the youth movements and to the support these individual young people enjoyed from the remaining community in the ghetto.

But it wasn’t only the uprising as the final communal act in April/May 1943 that embodies the spirit of community which motivated and drove the young people of the various youth movements. An impressive list of public activity that they undertook and performed in the ghetto informs their highly ideological stand of being proactive in the community especially in the face of an ever-worsening day-to-day reality. It is interesting to note how the youth movements altered their stance from being the young alternative to adult society from before the war, to engaging themselves in the woes of the whole society after the outbreak of war and the gathering oppression.

Their natural population target was all the children in the ghetto irrespective of whether they were members of their youth movement or not. With the closing down of schools in the ghetto, the youth counselors, madrichim, stepped into the breach and organized alternative educational activities as best they could. This included the cultural sphere like organizing easy access to libraries and other literary functions.

The activities of these young counselors was also colored by their particular Zionist orientation and thus we find that teaching Hebrew, learning about the Land of Israel, and organizing projects connected with the Jewish National Fund or The Keren Kayemet were often at the heart of the activities of the Zionist youth movements. It should be noted that the youth branch of the Bund party which was anti-Zionist and steeped in Yiddish culture to the exclusion of Hebrew would naturally be involved in activities not connected to the Land of Israel.

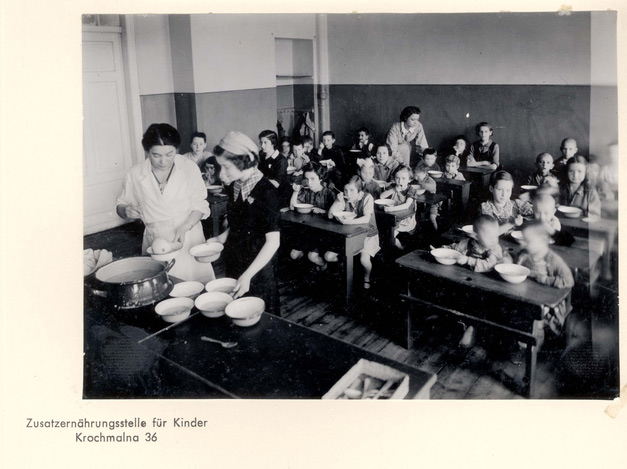

However the overriding component in all the endeavors of the various youth movements was to strengthen the failing spirits of the suffering Jewish population, young and old in the ghetto. The work with young people was paralleled with public kitchens that were organized in the ghetto to help as many needy people as possible with a bread and soup portion. This work was accomplished with the aid of the Judenrat, the Joint Distribution Committee and other organizations, and with their financing. Youth group communes in Nalewski and Dzielna streets in Warsaw became locations of spiritual and physical succor to many people, among them many literati and other members of the intelligenstia who were dying of hunger because they couldn’t fend for themselves.

Zivia Lubetkin survived the Warsaw Ghetto uprising after she served as a leading authority in the ghetto and during the rebellion itself. Her contemporaries described her as having at once an unassuming presence and a quiet, commanding manner of talking which granted her an authoritative standing amongst her peers. She was one of the very small numbers that managed to remain alive and were led out of the ruins of the ghetto through the sewers. She emigrated to the Land of Israel mid-1946 and was invited to the Kibbutz Congress convened in Kibbutz Yagur in June, 1946, where in a ground-breaking address she spoke, among many other topics, about the source of the moral strength needed by the Jews in the ghettos for their very survival; the collective. I quote from her book based on the address just mentioned, In the Days of Destruction and Revolt:

“What gave us this moral strength? We were able to endure the life in the ghetto because we knew that we were a collective, a movement. Each of us knew that he wasn’t alone. Every other Jew faced his fate alone, one man before the overpowering, invincible enemy. From the very first moment until the bitter end, we stood together, as a collective, as a movement.”5

She also laid special emphasis on the strength of the movement and its ability to make demands on its members for the betterment of all. It was the moral education prevailing in the youth movements that inculcated a revolutionary understanding of the existence of the Jewish people and the sovereignty of man in general.

The Story of a Young Woman in a Labor Camp

From the above story of interaction between hundreds and thousands, the following life story highlights the efforts of one Jewish woman prisoner in a German labor-camp to motivate her co-prisoners to fight for survival in the difficult conditions of the camp.

Lili Kasticher-Hirt was born in Yugoslavia in 1923 and in 1944, when she was twenty-one years old, she was taken with an aunt on a German transport to Auschwitz. Her aunt was killed and, due to her youth, Lili was selected for work. Early on, her Kapo found out that Lili was artistic and read palms and after Lily survived a private session of palm-reading with the Kapo, she enjoyed improved conditions in Auschwitz until she was transferred to a small labor camp in the Sudeten area of Czechoslovakia called Ober-Hohenelbe.

It was in this camp of several hundred women who were employed in making radios and electronic devices for the German air-industry that Lili Kasticher-Hirt came into her own. Drawing on hidden reserves of will-power, she initiated a "culture-hour" on every second Sunday afternoon during which she persuaded the women to attend a group meeting, held in the barracks, at which the women were urged to create something artistic, whether a poem, a story, some music, or a drawing. The idea was to counter the German effort to extinguish the human soul in the prisoner’s body and to motivate the young women to fight for the vestiges of their humanity.

The difficulty of generating the necessary energy to do anything beyond mere work and survival is to be deduced from the fact that only about twenty women had the strength to join her initiative.

Lili survived the Holocaust and returned to Novy Sad in Yugoslavia, where she found her step-mother and brother. She married, gave birth to a son and immigrated to Israel in 1948. In 1958 she had a daughter in Jerusalem, all the while continuing to write poems and her memoirs. She passed away in 1973.

Lili’s story captures the essence of the power of one individual to galvanize the energies of others under the most difficult of circumstances. Even some of those who merely observed the activities of this small group on a Sunday afternoon in a German labor camp testified to the fact that this small community of prisoners maintaining their humanity by means of clandestine artistic efforts helped them to preserve the memory of life before the war, and ultimately, to survive.6

A Second Philosophical Note

Dehumanization of victims all across Europe was a cornerstone of the Nazi system of subjugating populations and administering conquered territories. They fine-honed this aspect of inhumanity to man, to the ultimate. The three quotes presented in the first Philosophical Note above open a small window on this subject. Frister speaks about his reaction to the absolute immorality imposed on the prisoner. Kertesz’s statement touches on the physical pain that had to be endured and Primo Levi describes the virtually total lack of support that one might have hoped for from fellow prisoners.

In this second philosophical note, we return again to Primo Levi for further illumination in trying to plumb the depths of human depravity whilst desperately seeking a sliver of light in the darkness. Thus, what follows is evidence from Levi that despite everything, goodness and solidarity, even if diminished, was to be found in slivers here and there.

Many characters people the Auschwitz world that Levi provides for us in his various books. Two in particular stand out as personalities in the camp and in Levi’s life that provide a counterweight to the lack of human solidarity that he described (above). Alberto Dallavolta became a steadfast friend in Auschwitz and, living in the same block, an unbreakable bond of mutual support grew between the two Italian prisoners to the point where Alberto was for Primo one of the reasons he was able to survive.

Describing just one of the incidents that they experienced together will help the reader grasp the difficulties of finding human solidarity in the camp.

Thirst was sometimes a severe problem the prisoners had to deal with, if even for the prosaic reason that pipes had burst and the camp authorities weren’t rushing to fix the problem. Levi describes one such occasion when, suffering from unbearable thirst together with all the men in his work unit, he discovered a slowly dripping water pipe.

What did he do?

“A litre, perhaps, not even that. I could drink all of it immediately, it would have been the safest way. Or save a bit for the next day. Or share half of it with Alberto. Or reveal the secret to the whole squad. I chose the third path, that of selfishness extended to one who is closest to you.” 7

The problem and the pain of this description aptly convey the extreme difficulties of forging a solidarity within the compass of prisoner life in a camp.

The second character was another Italian, Lorenzo Perrone, who was a bricklayer by profession and a taciturn, silent man for whom work was top priority. His Italian firm had been transferred to work in Auschwitz for the Germans and, as such, he was not a prisoner but an Italian civilian worker receiving German pay. Levi had the great fortune to be teamed with Lorenzo for a while and the Italian connection was enough to trigger a formidable quiet humanism in the Italian civilian worker. Enjoying conditions and provisions that were much better than the prisoners, Lorenzo brought Levi an additional portion of daily soup for the next six months. This providential gift, certainly acquired at risk to Lorenzo, Levi shared with Alberto on a daily basis, for Alberto and Levi shared everything that came their way.

This token of solidarity in a universe of millions suffering, was clearly much more than a token to the three men involved. Lorenzo was later recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations.

It does help us put the three examples of solidarity described above in the heart of the article into a wider perspective and enable the reader to see the narrowing of opportunities for this kind of behavior as the Holocaust gathered momentum.

Conclusion

This article has attempted to shift the emphasis in any thinking on the Holocaust from the murder of six million to the fabric of life and the weave of human interaction under the weight of German oppression during the war. The general focus as stated above in the introduction is on Jewish life with various examples of how different groups and individuals reacted to the Nazi threat in different contexts like the ghettos and the camps.

The philosophical note sounded at the outset of the article articulated the extreme difficulties that had to be encountered and overcome in any attempt at maintaining a human face. The three examples presented in the heart of the article are a testimony to the human spirit in adversity.