- Years Wherein We Have Seen Evil, Volume 2, p. 165.

- Dawid Sierakowiak, The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 37.

- Yitskhok Rudashevski, The Diary of the Vilna Ghetto (Israel: Ghetto Fighters House, 1973), p. 106.

Introduction

This article will introduce the concept of spiritual resistance during the Holocaust and present ways in which the lessons learned from such unarmed resistance can be taught in the classroom.

By introducing students to examples of spiritual resistance, the teacher can facilitate discussions on how people survived during the Holocaust, and the personal values that contributed to their fight for survival.

In Holocaust terminology, “spiritual resistance” refers to attempts by individuals to maintain their humanity and core values in spite of Nazi dehumanization and degradation. Such unarmed resistance came in many forms, religious and non-religious, cultural, and educational. It proved that physical survival was not the only decisive quality of a person and it certainly was not the only matter of importance even to people in the most dire conditions.

While this article presents several examples of such resistance, its aim is to present a basis for a more general discussion on the global issues of morality, humanity, and core personal values.

What was Spiritual Resistance During the Holocaust?

During the years of the “Final Solution” between 1942 and 1945, Jews and several groups of non-Jews targeted by the Nazi regime were interned, enslaved, humiliated, and exterminated in ghettos, concentration camps, and death camps. Finding food, staying warm, providing a roof over their heads, and taking care of their families were difficult challenges that they had to meet on a daily basis. Nazi restrictions and modes of degradation were definitely aimed to physically destroy. However, the isolation of ghetto life was intended to incur social separation in addition to controlling and monitoring Jews. It was under these circumstances that some Jews “found within themselves the inner strength to examine their situation and to try and find meaning in the events that controlled their very existence.”1

Others established cultural programs in ghettos and concentration camps as they realized that physical sustenance would not be the sole route to survival. Such religious, cultural, and educational activities are termed “spiritual resistance,” for resistance is not only the struggle against, but it is also the struggle for. In ghettos and camps, Jews struggled for humanity, for culture, for normalcy, and for life.

In order to teach the values of spiritual resistance, it is important to understand specific examples of such activity. A diary is a form of spiritual resistance. Written from within the walls of a ghetto or the barbed wire of a concentration camp, a diary is testimony and reflects the desire to leave a legacy for future generations. One example of such a diary is that of David Sierakowiak, interned in the Lodz Ghetto and later deported and murdered in Auschwitz. He left a legacy of seven journals, five of which were recovered after the war. In one entry, dated September 10, 1939, David writes, “Tomorrow is the first day of school. Who knows how our dear school has been. Damn the times when I complained about getting up in the morning and tests. If only I could have them back.”2

The mere fact that David kept a journal is significant, though it is of course fascinating to notice what he wrote and valued. While starving and tired and even after his mother had been taken away, he longed for school and for normal life. In later entries he expresses hope for the future though realizes that it “seems just another pipe dream.” This diary provides testimony that could not be obtained in any other way. Furthermore, it forces one to think about the strong personal integrity that David and others had even under such degrading, humiliating circumstances.

Education is a form of resistance. In his diary, Yitzkhok Rudashevski writes about the library in the Vilna Ghetto. The Jewish community of Vilna was known for tremendous study and Jewish learning. Therefore, it is not surprising, in light of our knowledge on spiritual resistance, that when confined to the ghetto, Jews built a library and were so excited by each acquisition, that there was a celebration for the 100,000th book. Yitzkhok writes, “Hundreds of people read in the ghetto. The book unites us with the future. The book unites us with the world. The circulation of the 100,000th book is a great achievement for the ghetto, and the ghetto has a right to be proud of it.”3 The establishment of the library itself is an act of spiritual resistance, but Yitzchok’s diary entry also highlights the fact that he was still thinking about the future. All hope was not lost and Jews in the Vilna Ghetto wanted to maintain their dignity as human beings.

Cultural activities are a form of resistance. In the Terezin Ghetto, children performed an opera called Brundibar, composed before the war by a Czech Jew named Han Krasa but not performed until he and many of the original performers had been deported to Terezin. A set was designed, pieces were rewritten to include the instruments available in the ghetto, and artists in the camp designed posters to advertise the performance. Furthermore, the very subject of the opera was easy to relate to. The opera tells the story of children who sing in the marketplace to raise much-needed money for their sick mother. The organ player Brundibar chases them away, but with the help of some outsiders, the children defeat Brundibar and continue to sing in the square. All those watching and performing the opera understood that Brundibar represented Hitler and were uplifted, even if only briefly, by the fact that evil could be defeated by good.

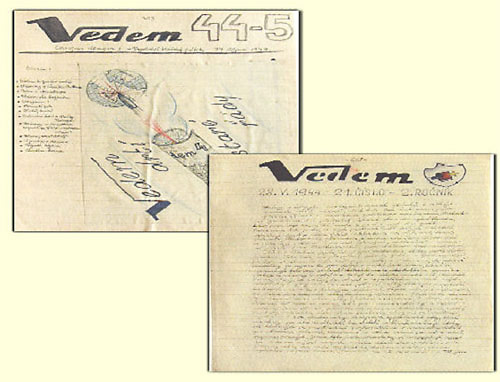

In another example of spiritual resistance in Terezin, several teenage boys compiled a secret magazine titled Vedem, which printed prose, poetry, and editorials that provided an outlet for their emotions. In a touching letter, one of the teenagers wrote, “We no longer want to be an accidental group of boys, passively succumbing to the fate meted out to us. We want to create an active, mature society and through work and discipline, transform that fate into a joyful, proud reality.” This statement is an act of resistance. The boys in Home Number One were not only fighting for their right to live, but for their right to exist as educated, valued individuals.

It is usually assumed that a student who studies the Holocaust learns about the deprivation and humiliation that the Nazi regime instituted. They learn about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the ways in which Jews smuggled food, stole clothing, and tried to appear strong and able in order to avoid the gas chambers. However, one of the unique aspects of this situation is that those types of behavior were not enough for those interned in ghettos. It was not enough to keep one’s body physically alive. In many instances, Jews in ghettos and camps continued observing religious traditions, using their creative skills, and maintaining communal life.

What Can Be Learned from Spiritual Resistance?

Aside from the necessary facts required in a lesson on the subject of “spiritual resistance,” there is a global message that should be taught and learned. These people attempted to preserve a sense of self in impossible conditions. They managed to create a personal – albeit tenuous – world in which small, day-to-day decision-making mattered, as a way of preserving internal meaning.

How Do I Teach this Concept in My Classroom?

The pedagogical philosophy at Yad Vashem focuses on the face of the individual. It is through learning about personal stories that concepts can come alive for students and help them relate empathetically to the people they are learning about. Use the resources provided in this newsletter, particularly the lesson plan devoted entirely to the subject of “spiritual resistance” and on the Yad Vashem website to personalize this concept. Finally, encourage your students to think about their own values and what they would choose to maintain from their own lives. What would they leave as a legacy for the future?