Introduction

In the summer of 1944, seventy years ago, there were still more than 77,000 Jews alive in the Lodz ghetto. When put into context, this number is particularly striking. The Jews of Poland had already been decimated. Lodz, which was originally intended to be a temporary ghetto,1 was actually the very last ghetto left in existence in Poland. The Jews in the Lodz ghetto could practically hear the thunder of the Russian artillery from the approaching front.

The Jews of the ghetto had been working as slave laborers for the Germans for four years. Busy supplying the German war machine with equipment and the German civilian economy with consumer goods, they continued to work until the last moment. In the summer of 1944, work orders were still being met, and factories still churned out their products. From September 1942 to the beginning of June 1944, a full year and a half, there had been no deportations. Life in Lodz had settled into a pattern and was relatively calm. The Jews had reason to be optimistic; they were productive and important to the German war effort. Then again, certain circles within the ghetto that had access to the news understood that all the other ghettos in Poland had been liquidated. While they hoped their fate would be different, at the same time they were skeptical.

It was a race against time. The news that managed to infiltrate the ghetto led them to understand that the Germans were losing the war and were retreating. The Jews left in Lodz hoped against hope that they would outlive the Nazi extermination machine. As Oskar Rosenfeld2 put it in his diary, "We will hold out. We will outlive you, you cannot destroy us…."3 In the ghetto the Jews tried to hang on, to escape "resettlement" for as long as they could.

They clung to this hope even when the situation changed abruptly in the summer of 1944. In the face of renewed deportations beginning in June 1944, the prisoners of the Lodz ghetto were caught between hope and despair. The tension and the tragedy of their last days and moments can be seen in their diaries, in the Lodz Chronicle and in the notices posted on the walls of the ghetto.

The Final Days

By the spring of 1944 the Lodz ghetto had existed for four years. Early on Hans Biebow, the head of the German civil administration of the ghetto, with the support of Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Ältestenrat ("Council of Elders"), issued orders for factories to be set up in the ghetto (called Arbeitsressorte, or work sections). The Jews confined in the ghetto provided these factories with very cheap labor, so that the factories served the Nazis as a source of easy profits and exploitation. Rumkowski believed that if the ghetto became productive and contributed to the German war effort, it might be able to survive. In this way, more and more ghetto dwellers began to work in factories established in the ghetto, until by 1944, over 90% of the ghetto was working.

As described in other articles in this newsletter, Biebow, along with Arthur Greiser, the Nazi chief of the Warthegau, had been instrumental in ensuring that the ghetto would not be liquidated, since these two administrators were using the ghetto to get rich. Ultimately the ghetto produced textiles, cabinets, furniture, shoes, and gloves, and performed tannery, furrier, upholstery, and locksmith work. Many of the consumer goods produced in the ghetto were purchased by famous German department stores. The ghetto was also heavily involved in the armaments industry, producing parts for munitions, shells and other equipment needed for the war effort. The exploitation of the Jews imprisoned in the ghetto ultimately yielded a net profit to the ghetto administration estimated at a sum total of 350 million reichsmarks ($14 million).

However, in the spring of 1944, Nazi ideology triumphed over the greed of Greiser and Biebow. After discussing the idea for over a year, the Nazis decided, finally, to liquidate the Lodz Ghetto.

Himmler "unswervingly stuck to the Final Solution,"4 as Albert Speer, Hitler's Armament's Minister wrote. Speer, who understood the desperate need of the German war machine for continued means of production, and understood, as well, the fact that the Lodz ghetto factories could help in assuaging this need, argued against the ghetto's destruction. However, he was not able to dissuade Himmler from liquidating the ghetto, though the decision was totally contrary to Germany's war effort. Speer wrote, "This points to a truly bizarre situation, utterly eccentric in its tragedy. Greiser's fanatical antisemitism, his hatred and his obedience outweighed any rational consideration. He accepted the execution of production together with the execution of the Jews."5

The Perspective of the Ghetto Dwellers

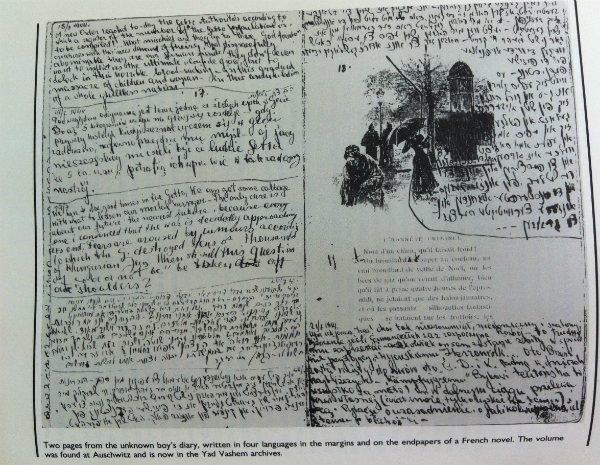

In the following diary entries, which begin in June, 1944 with the news that deportations are about to begin again after 1 1/2 years of quiet, the confusion and uncertainty of the ghetto population is palpable. Most of the entries come from an anonymous diary that was written in four languages – Polish, English, Yiddish and Hebrew – in the margins of a book (ironically, the French novel The Truly Rich, Les Vrais Riches).

The diary is short, but quite intense; it begins in May, 1944 and ends in August, 1944. It was written by a young man who never gives his name; we will call him the Unknown Diarist. He was apparently connected to circles in the ghetto that may have had access to a radio or to newspapers, because he is very aware of the progress of the war. There are different theories as to why he wrote in different languages – he may have used Hebrew when he didn't want his younger 12-year old sister to understand. His English is very flowery and formal. The entries in Yiddish and Polish, the languages he apparently spoke most fluently, seem to be the most uninhibited and raw. Apparently, the diarist took the diary with him to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. The diary was found there after the war.6

June 16, 1944 [written in Polish]

"We are suffering so much….Again they are getting 500 people read to be sent out of the ghetto. Again uncertainty overtakes us. Oh! Was all our suffering in vain? If they annihilate us now in their usual manner, why didn't we die in the early days of the war?! My little sister complains that she has lost all will to live – how tragic this is! Why, she is only 12 years old. Will there be no end to our suffering? If so, how? Oh God, oh humanity, where are you?"

The final liquidation of the ghetto began on June 23, 1944. Within three weeks, ten transports with 7,176 Jews had been sent from Lodz to the newly reactivated death camp at Chelmno.

Oskar Rosenfeld, Saturday, June 24, 19447

"The ghetto is agitated because the railroad cars that carried off yesterday's transport are already back at Radogoszcz station."

The curious fact noted by Rosenfeld in his diary was interpreted, quite correctly, by the ghetto as significant. Rosenfeld and others inferred from this that the transport traveled only a short distance to its unknown destination. The ghetto dwellers remembered the frequent transports in 1942, when 55,000 Jews were deported between January and May, and almost 20,000 were deported during the September "Sperre", all to Chelmno, only 50 km from Lodz. The trains had returned quickly then, as well. The rumors were correct; Chelmno reopened on June 23, 1944 in order to liquidate the Jews of ghetto Lodz.

Unknown Diarist, Sunday, June 25, 1944

"[T]here is a pall over the ghetto. Twenty-five transports have been announced. Everyone knows that the situation is serious, that the existence of the ghetto is in jeopardy. No one can deny that such fears are justified. The argument that not even 'this resettlement' can imperil the survival of the ghetto now falls on deaf ears. For nearly every ghetto dweller is affected this time. Everyone is losing a relative, a friend, a roommate, a colleague.

And yet – Jewish faith in a justice that will ultimately triumph does not permit extreme pessimism. People try to console themselves, deceive themselves in some way. But nearly everyone says to himself, and to others: 'God only knows who will be better off: the person who stays here or the person who leaves!'"

Chelmno proved to be too slow and inefficient for the Germans. The Soviets were rapidly approaching and the Lodz ghetto had to be liquidated – so the Germans changed their strategy. Auschwitz had become the main extermination camp in this period, and the Germans understood that it would be more efficient to send the Jews of Lodz to Auschwitz to be killed. While they worked out the logistics, deportations to Chelmno were stopped, and there were no new deportations during a two-week period at the end of July. The ghetto inhabitants did not know the reason why the deportations had been stopped, they only knew that they had.

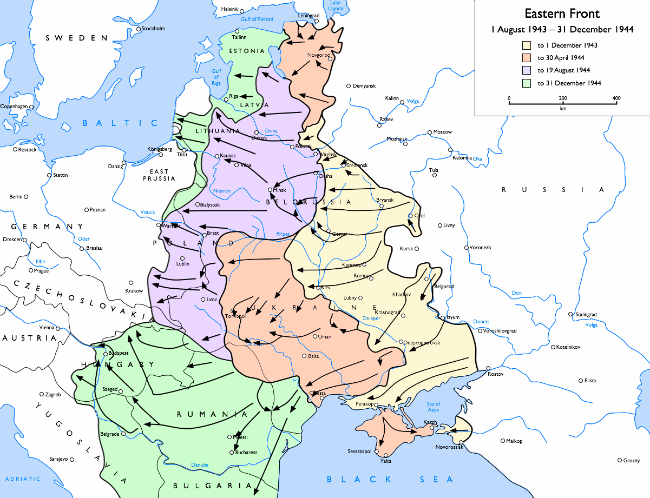

During this time, especially, the Jews of the Lodz ghetto were in a frenzy of hope and worry and expectation. Despite the prohibition on radios, some Lodzians were getting news of German retreats, and this made them optimistic. The Soviets had initiated "Operation Bagration," their summer offensive, on June 22, 1944. The Soviets destroyed an entire German army group, defeated German forces in Belorussia and began a sweep through eastern Poland. On July 3, 1944 the Soviets captured Minsk, and on July 9, 1944, British and Canadian troops captured Caen, France.

Unknown Diarist, July 8, 1944 [written in Polish]8

"Everybody and everything makes one believe that this diabolic game is definitely coming to an end, for they're [the Germans] getting hit on their heads as never before. But this is of no help to us, since deportation lists continue to be compiled. […] We are now – how to put it – full of hope and despair, full of stoical resignation and, at the same time, full of trusting expectation. […]"

Unknown Diarist, July 10, 1944 [written in Yiddish]9

"[W]e are now facing the terrible question of our fate, of our survival. We know that every Jew yet living makes his [the German beast's] heart heavier, that he still lusts for our blood. The men, women, children killed, executed, buried alive are still not enough for his insatiable murderous stomach. Now, in his final moments, he's got hold of Hungarian Jewry, solving the problem his way. What then will happen to us?! Can he accept the thought of a few broken Jews – just skulls – still alive? [...] one still wants to live. […] We all know that after death there is no revenge – and in all of us there burns such hate for the Germans, such yearning for revenge – that we must live on!!!"

On July 20, 1944 there was an attempt by German officers to assassinate Hitler, which cheered the ghetto inhabitants even though it failed.

Unknown Diarist, July 21, 1944 [written in Polish]10

"At present, mixed feelings possess us; at one moment we are full of hope, in another we are seized by that so well-founded resignation, to the point of feeling choked. Because, can one suppose that they would let us live? [...] it is difficult to foresee what the next days have in store for us!...."

Unknown Diarist, July 23, 1944 [written in Hebrew]11

"There are rumors that make us happy and encourage us. General Keitel, head of the general staff, resigned. The Russians are approaching Warsaw. The opposition inside Germany is growing in strength and numbers. There are many towns where the Gestapo is no longer in control. There are rumors that are difficult to believe…."

The Lublin-Brest Offensive, part of Operation Bagration, pushed Soviet forces into eastern Poland towards the Vistula River. By July 21, 2014 the Red Army had reached the Bug River. By July 25, 1944 it had reached the Vistula. On July 24, 1944 the city of Lublin was liberated, and with it, the Majdanek extermination camp.

Unknown Diarist, July 25, 1944 [written in Hebrew]12

"Two hours past midnight.

I can't sleep because of the bedbugs and my own agitation. For five years I kept my patience, and now it's suddenly gone. One can feel the coming liberation in the air. The Russians have captured Lublin. In Germany there was an attempt on Hitler's life. They want to end a war they definitely oppose. […]The end is knocking on our doors. Another moment and, if they let us alone, we'll be free. Just the idea makes me cry…."

Unknown Diarist, undated in July, 1944 [written in Polish]13

"…I want so much to be on the other side of the barrier that I get sick at the thought…We assume more than ever that they'll let us remain alive – but every one of us knows that one cannot be sure, for one can scarcely expect logic from beasts of prey.[…] My days pass in utter tension and excitement. […] May the next hours bring us liberation from our inhuman bondage!"

On July 28, 1944, Soviet troops took Brest-Litovsk. By August 2, 1944, the Soviets seized bridgeheads on the Vistula River near Warsaw. News of fighting near Warsaw and the progress of the Red Army sweeping into Poland gave the ghetto inhabitants further reason to believe that the end was at hand.

Unknown Diarist, July 28, 1944 [written in Polish]14

"Can anyone imagine a convict in his gruesome cell hearing quite clearly the blows of a hammer on his prison walls? We are now able to hear these blows, every night there are air raid sirens. No wonder, they themselves admit that the fighting is taking place in Ost-Warschau [East Warsaw]. What magic words!"

Unknown Diarist, undated in July, 1944 [written in English]15

"I am in a state of terrible excitement mixed with disbelief and fear. Who of us subject to such suffering could believe that we should get out, that we should be among those who survive! Oh! If I were a poet, I should say that my heart is like the stormy ocean, my brains a bursting volcano, my soul like… Forgiveness, I am no poet. Imagine a Jew of Litzmannstadt-Ghetto not wholly deprived of imagination when he is told the few magic words […] 'Bitter fighting has reached the borders of Warsaw.' […] If we lived this long, perhaps we shall live until the moment of our dreams. If we live to see our capital taken it is nearly certain that we'll also see Litzmannstadt delivered. Meanwhile, I am like a lunatic, feverish with impatient expectation, full of hope and fear, I should like to become a few weeks older and still be alive!"

However, after the Russian army swept partially through Poland, it halted completely at the periphery of Warsaw, on the other side of the Vistula River. This changed the situation completely. The Soviets no longer advanced; they waited as the Poles launched an uprising against the Germans.

Meanwhile, after the break in deportations at the end of July, the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto began again in earnest on August 7, 1944. This time, the trains were headed for Auschwitz. The fates of the Jews imprisoned in the Lodz ghetto were now sealed.

Unknown Diarist, August 3, 1944 [written in English]16

I write these lines in a terrible state of mind. All of us have to leave Litzmannstadt-Ghetto within a few days. When I first heard this, I was sure that it meant the end of our unheard-of martyrdom equatanously [simultaneously] with our lives, for we were sure that we should be vernichtet [German: destroyed] in the well-known way of theirs. What for to have suffered 5 years of Ausrottungkampf [German: annihilation war]?.... And Biebow, the German Ghetto-Chief gave a speech to the Jews, the essence of which was that this time they should not be afraid of being dealt with in the same way the other deported have been – because of a change in war conditions, 'und damit [das] Grossdeutsche Reich den Krieg gewinnt, hat unser Fuhrer befohlen, jede Arbeitshand auszunutzen [German: and the Fuhrer has ordered that every worker is to be used in the war effort.]' … Now that we have to leave our homes, what will they do with our sick? With our old? With our young? Oh God in heaven, why didst thou create Germans to destroy humanity? I don't even know if I shall be allowed to be together with my sister! I cannot write more, I am terribly resigned and black-spirited!"

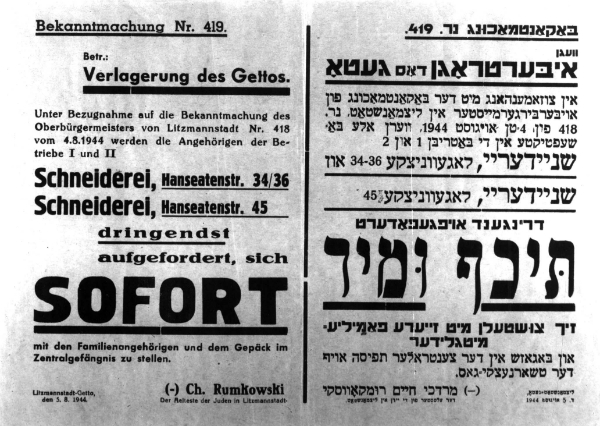

The Germans now increased their level of deception to ensure that deportations would go smoothly. New notices appeared in the ghetto promising the Jews that workers would be deported with their families, and factory equipment was loaded into the cattlecars together with the Jewish laborers. The Germans worked hard to give the impression that the Jews of the ghetto were being sent to work within Germany - nothing more devious than that.

"Announcement No. 417

On the instruction of the Oberburgermeister [mayor] of Litzmannstadt, the ghetto will be evacuated. The workshop crews will go as units, together with their families

THE FIRST TRANSPORT DEPARTS

ON 3 AUGUST 1944

5000 PERSONS

MUST REPORT DAILYLuggage is not to exceed 20 kg per person.

The first transport includes:

Plant No. 1 of the Tailors' Division, 45 Lagiewnicka Street, and Plant No. 2, tailor shop, 36 Lagiewnicka Street

The families of the evacuees will go with the same transport so that no family will be torn apart.

Other plants will be informed separately about their departure.

The evacuees are to report at the Radogoszcz station.

The first transport leaves at 8 AM. Therefore the evacuees are to report to the station at 7AM at the latest.

Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski

The Eldest of the Jews

Litzmannstadt-ghetto, August 2, 1944"17

Biebow worked hard to encourage this false impression as well. He appeared in different shops, speaking to workers, trying to persuade them to leave. He made an address to the workers in the tailors' workshops on August 7, 1944 in which he said that it was necessary to transfer workers to lands from which thousands of Germans were taken and sent to the front; these workers had to be replaced:

"Siemens, A.G. Union, Schukert, every place where munitions are made, need workers. In Czenstochau [Czestochowa], where workers are employed in munitions plants, they're very satisfied, and the Gestapo is also very satisfied with their work. After all, you want to live and eat, and you will have that…."18

In this speech Biebow said no less than, "I assure you that we'll make every effort to continue doing our best, and – by transferring the ghetto – save your lives."19

Rumkowski, as well, encouraged the Jews to report for transports.

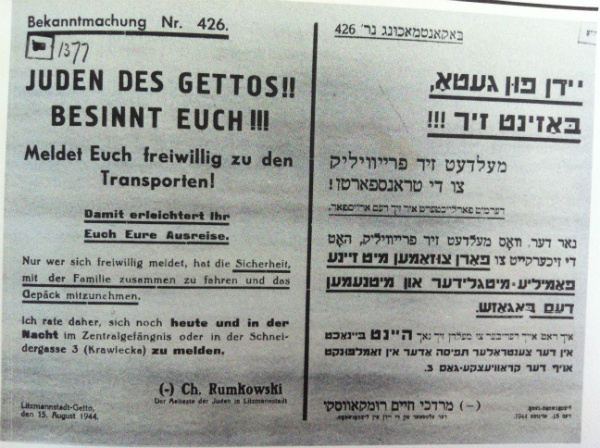

Despite these urgings, only small numbers of people reported voluntarily for the transports. The Jews in the ghetto understood that the end of the war was only a matter of time; they tried to outlast the German efforts to deport them. The whole ghetto was holding its breath. One diarist, Jakub Poznanski recorded, "People don't want to leave even the worst holes in the ghetto."20

The tone of the notices began to change as a result of the lack of laborers voluntarily reporting for deportation.

"Announcement No. 426

JEWS OF THE GHETTO,

COME TO YOUR SENSES!!!

VOLUNTEER FOR THE TRANSPORTSYou will make your own departure easier

ONLY THOSE WHO REPORT VOLUNTARILY HAVE THE ASSURANCE THAT THEY WILL GO WITH THEIR FAMILIES AND WILL BE ABLE TO TAKE ALONG LUGGAGE.

I advise you to report TONIGHT to the Central Prison or at the assembly center on 3 Krawiecka Street.

Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski

Eldest of the Jews

Litzmannstadt-ghetto, 15 August 1944"21

Unknown Diarist, August 20, 1944 [written in Hebrew]22 "Days come and go. There are rumors that we won't have much longer to wait. The Germans admit they've retreated from Lublin, Bialystok, Brisk [Bresk Litovsk], Dinanburg and other places…. I worry terribly, because despite everything the situation is still unclear. Who can predict our future? Maybe they won't kill us. How I would like the privilege of going to Eretz Israel…Only a Jewish heart can feel the depth of our pain. If God helps us, we will live and console ourselves."

Unknown Diarist, undated [written in Yiddish]

"It is now five full years that we have been tortured in the most terrible way. Describing all our pain is as possible as drinking all the ocean's water or lifting the earth. I don't know if we'll ever be believed."23

After all the hope and despair of the final months in the ghetto, the Germans ultimately succeeded in clearing it out. Transports carrying about 70,000 of the last Jews left in the ghetto were sent to Auschwitz, where most of the Jews were murdered in the gas chambers at Birkenau. The last transport left the Lodz Ghetto on August 30, 1944, apparently with Rumkowski as one of the passengers. Rumkowski, too, was taken in by the Germans' deception; Biebow even gave him a letter of introduction, commending his administrative ability, to "protect" him. But Rumkowski, like over 67,000 Jews of the Lodz ghetto, was murdered at Auschwitz.24

Approximately 900 Jews remained in the ghetto to clear it out and were saved when they were liberated by the Russian army on January 19, 1945. No precise figures are available for the number of Lodz Ghetto inmates who survived; estimates range from 7,000-10,000, or about 5% of the ghetto population.

Some of the writings contained in this article were part of the Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto and were found in Lodz after the war when the ghetto was cleaned out, others were part of diaries brought by their authors to Auschwitz and found there. Though in many cases the authors did not survive, their writings did. They reflect the impossible tension experienced by the Jews in Lodz in the final days of the ghetto as they veered between hope and despair.

The inspiration for this article and the idea for the use of the diaries cited here come from a talk given by Michal Unger at Yad Vashem on July 3, 2014. The article's title comes from a diary entry made by an anonymous young man on July 8, 1944, provided in full in the text.

- 1.As the Regierungspraesident for the Lodz region, Friedrich Uebelhoer, put it on December 10, 1939, "The creation of the ghetto is, of course, only a temporary measure. I reserve to myself the decision concerning the times and the means by which the ghetto and with it the city of Lodz will be cleansed of Jews. The final aim (Endziel) must in any case bring about the total cauterization of this plague spot." Y. Arad, Y. Gutman, A. Margaliot (editors), Documents on the Holocaust, Selected Sources on the Destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland, and the Soviet Union, (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1981), pp. 192-195.

- 2.Rosenfeld was a Zionist, originally from Moravia, who studied at the University of Vienna. He worked with Theodor Herzl, founding Vienna's first Jewish theater and editing the Zionist weekly newspaper, Die Neue Welt. He moved to Prague when Germany annexed Austria in 1938. From Prague he was deported to the Lodz Ghetto. He was a writer and a translator of Yiddish literature, and kept a diary while in the Lodz ghetto, as well as writing for the Ghetto Chronicle. He met his death at Auschwitz in August, 1944.

- 3.Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides, ed., Lodz Ghetto: Inside a Community Under Siege (New York: Viking Penguin, 1989), p. 1, from the private diary of Oskar Rosenfeld, 17 February 1942.

- 4.Adelson and Lapides, Lodz Ghetto, p. 413, quoting Speer, Infiltration¸ (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1981).

- 5.Ibid., p. 414, quoting Speer, Infiltration.

- 6.Adelson and Lapides, Lodz Ghetto, p. 423. All of the entries of the Unknown Diarist come from this book.

- 7.Ibid., p. 417.

- 8.Ibid., p. 428.

- 9.Ibid., p. 429-430.

- 10.Ibid., p. 434

- 11.Ibid.

- 12.Ibid.

- 13.Ibid., p. 436.

- 14.Ibid.

- 15.Ibid., p. 436-437

- 16.Ibid., p. 438.

- 17.Ibid., p. 440.

- 18.Ibid.

- 19.Ibid., p. 441.

- 20.Jakub Poznanski survived the final days of the ghetto in hiding, and ultimately survived the war. Adelson and Lapides, Lodz Ghetto, p. 445.

- 21.Ibid., p. 448.

- 22.Ibid., p. 439.

- 23.Ibid.

- 24.There are a number of different versions as to how Rumkowski perished. Some sources claim he was beaten to death by other Jews from the ghetto. Others claim he was welcomed on the platform at Birkenau by the Nazis, who told him that he and his family would be given a tour of the facilities, and then he was taken to the crematorium and burned alive. Another version has Rumkowski failing the selection process and being gassed together with the other Jews. Ibid., p. 493.