- Henryk Ross, cited in Martin Parr & Timothy Pruss, Eds., Lodz Ghetto Album: The Photographs (London: Chris Boot Ltd., 2004), p. 27.

- In 1944, the Germans started the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto and to deport the remaining Jews to Chelmno and Auschwitz. 800 Jews were left behind in order to clean it and 8 mass graves were prepared for them. However, the Nazis did not manage to murder them before the arrival of the Soviet army and the liberation of the ghetto in January 1945.

- Janina Struk, quoted in Rose George, The Ghetto, Less Gritty, accessed December 8, 2014.

- Roman Halter, quoted in: The Last Ghetto: Life and Death in Lodz, The Independent, 24 January 2005, accessed December 7, 2014.

- George Eisen, Holocaust and Play in the Holocaust: Games among the Shadows (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), page 78.

- Henryk Ross, cited in Lodz Ghetto Album, p. 155.

- Robert Jan van Pelt, Foreword, Lodz Ghetto Album, p. 7.

- Rose George, The Ghetto, Less Gritty, at, accessed December 8, 2014.

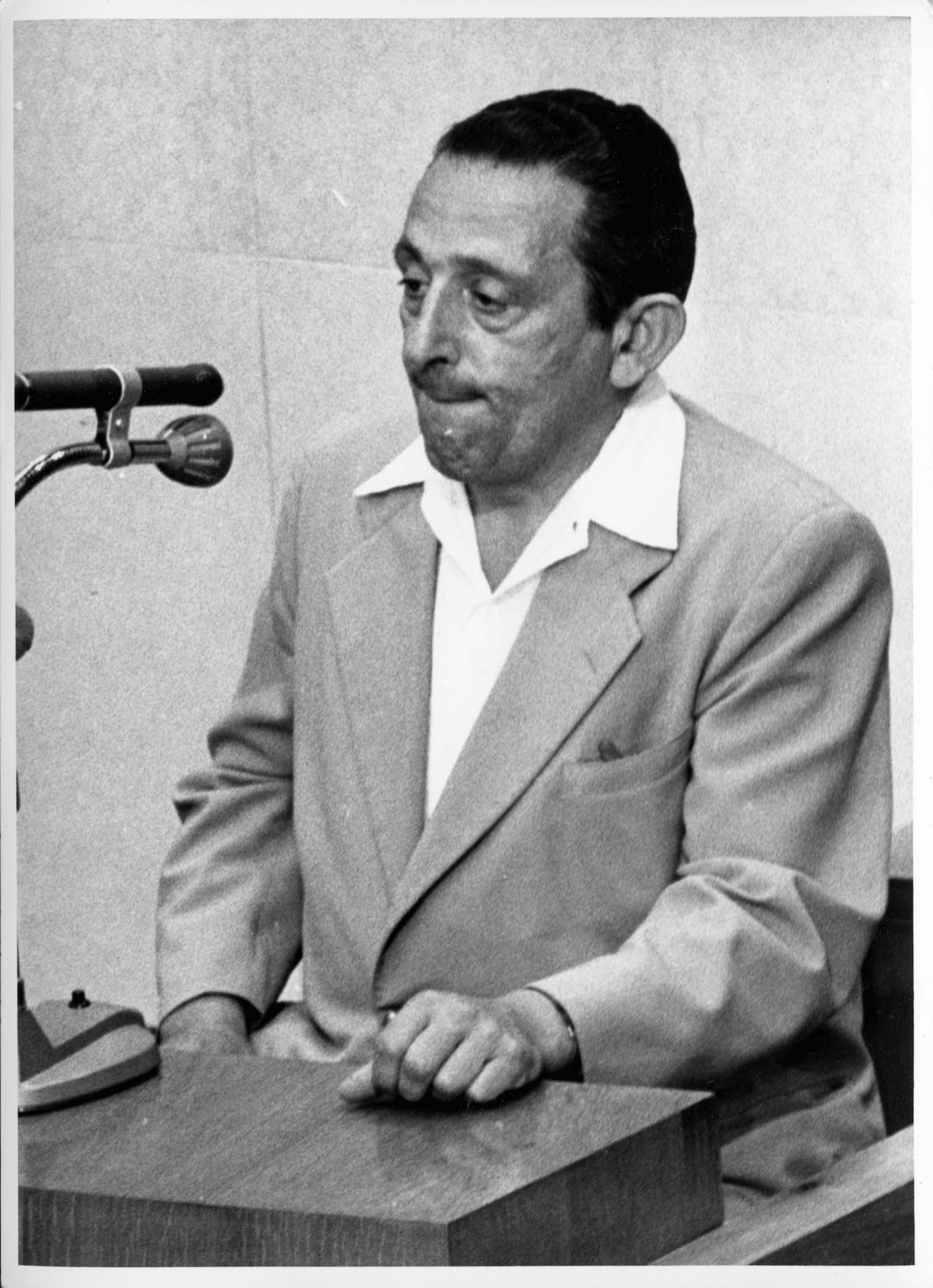

One of the most impressive picture collections that survived WWII was created clandestinely by the Jewish photographer Henryk Ross. Ross was born in 1910. Before the war he had been a sports photographer for a Warsaw newspaper.

When the Lodz Ghetto was sealed by the Germans in May 1940, Ross was forced to move into the ghetto. He managed to get a job as one of the official photographers in the ghetto. Along with his colleague Mendel Grossman, Ross was in charge of producing identity and propaganda photographs for the Department of Statistics in the Lodz Ghetto. Due to his task, Ross had access to film and processing facilities in the ghetto. He used these to secretly document the conditions in the ghetto, the suffering of the Jews there, and the brutality of the Germans. His work was an act of resistance against the prohibition of the Germans and the ghetto authorities to take pictures that were not officially approved. He hid his camera underneath his coat, opened it slightly, and snapped the photographs. Ross exposed himself to dangers and risked his life in order to take the pictures. In this fashion, he accumulated thousands of pictures that tell us what life was like in the Lodz Ghetto.

When the liquidation of the ghetto began in 1944, Ross buried his archive in the ground of the ghetto, so it could be dug up and could bear witness to the persecution of European Jewry after the war.

"Just before the closure of the ghetto (1944) I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy, namely the total elimination of the Jews from Lodz by the Nazi executioners. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom."1

Henryk Ross stayed behind in the ghetto as part of the clean-up commando2. He survived the Holocaust, and located and dug up the documentary material after the war.

Ross's collection is exceptional. It portrays Jewish life in the ghetto through the eyes of a professional and skillful Jewish photographer who clearly loved and appreciated the capturing of people and social interactions. Ross felt compelled to do what he could in order to document Jewish life and by that to defy the Nazis' goal to annihilate the Jewish people and culture. The collection contains about 3,000 negatives and other ghetto records. Ross's "records of the tragedy" were used as evidence in the Eichmann trial in 1961.

Commemoration of Jewish Life in the Ghetto

Like Mendel Grossman's images, Ross's photographs depict familiar scenes of hunger, despair and death; some 20% of the inhabitants of the ghetto died of starvation. He photographed workers in the ghetto who had to go barefoot while pushing the carts that moved feces out of the ghetto – a dangerous job that often led to death by typhus. He photographed scenes of misery near the ghetto prison, and public hangings. He caught on film the deportations of the Lodz Jews to their deaths at Chelmno. He photographed people writing their last notes to their families, and children waiting behind chain-link fences to be taken to an unknown destination during the "Sperre", the horrifying deportation in September, 1942 where almost all the children under ten years old were taken from the ghetto, and later murdered at Chelmno.

However, his collection also includes photographs that strike us as unfamiliar in the context of the Holocaust and challenge our visual memory of the ghettos. Henryk Ross managed to find beauty even among the suffering that the ghetto population faced every day. He captured those moments whenever he had a chance. He photographed scenes such as a couple kissing behind a bush,birthday parties, ghetto receptions, love between women and their children, the joy of children playing, and the happy moments of ghetto residents. The people in these pictures smile, they are handsome and dressed nicely, and they seem healthy and happy.

These photographs are beautiful images, but they are disturbing at the same time. They were taken in the midst of destruction, humiliation, starvation and murder. It is hard to believe that pictures like this were taken in the Lodz ghetto. They are deceptive. They make it seem as though the conditions in the ghetto could not have been so terrible if these well-fed, well-dressed, healthy and happy people were enjoying life and celebrating. If one doesn't know the context, the history and the deathly reality of the Lodz ghetto, one could be deceived into believing that these images represent the daily life of all inhabitants. Thus, it is important to emphasize that these photographs stand in stark contrast to the reality that the majority of the ghetto inmates faced.

Ross's images depict only a tiny minority of the ghetto inmates – the more privileged people in the ghetto who managed to be employed as part of the ghetto administration, the Judenrat (Jewish council), or the ghetto police. The Nazis created a system in which the running and policing of the ghetto was in the hands of a Jewish minority. This ghetto elite lived under fairly better conditions than the majority of the Jews living in the ghetto. They lived a relatively easy life while others around them were starving to death every single day. Ross depicts private and intimate situations of the members of the ghetto elite that remind us of ordinary private photo albums.

What is disturbing is that these are the people that have been judged too easily for buying or bribing their way out of deportation or starvation. These are the people that have been dismissed by many as living the good life, while people died all around them. Pictures of these individuals are uncomfortable to look at because they are reminders of something that many don't want to acknowledge. Yet, the ghetto police uniforms, stars of David that all Jews were forced to wear, interrupt the idyllic scenes. They remind us that the people captured in the photographs were forced to live in the ghetto like everyone else, and that ultimately, most of them were deported and murdered during the Holocaust.

It is unclear why Ross took these private pictures and what kind of a relationship he had with the people depicted in them. It is possible that he was paid to take pictures for them; it is possible that he was friends with them; it is possible that he simply wanted to commemorate these beautiful scenes and social interactions.

For a long time the only pictures Ross took that were known to the public were his photographs depicting atrocities. The images showing the other side of the ghetto were unknown until 1997 – six years after his death – when his son made his collection accessible. This has probably much to do with the fact that the public didn't want to see these pictures. It is telling that Mendel Grossman's pictures of the Lodz ghetto are very well-known, even though Grossman did not survive to catalogue or explain them. Ross's pictures, however, remained unseen for almost sixty years, even though Ross survived and even gave testimony at the Eichmann Trial in 1961 based on his photos.

“He tried to get his pictures published in the 1950s, but no one wanted to know. The iconic pictures of the Holocaust were of atrocities, horrors. The message of these pictures is not so straightforward.”3

Holocaust survivor Roman Halter, who was sent to Lodz in 1940, explains that Ross's archive has been judged harshly, and that many Holocaust institutions hesitated when Ross offered his pictures.

"They wanted to use some of Ross's photographs, but never these of Jewish police. That just wasn't acceptable…." 4

One of the most shocking and disturbing images is that of two children playing the game "Jew and ghetto policeman". The child acting as the ghetto policeman is wearing a uniform and holding a stick as if hitting the boy in front of him. He is posing for the camera and smiling at the photographer. Both children look well-fed; they wear clean clothes, they don't look intimidated or scared. This picture raises many questions: what were the boys thinking when playing this game? Where did they get the uniform? What did adults think when seeing the children play? Why did the photographer photograph a scene like this?

The game was apparently very popular and it was played by children in different ghettos throughout the German-occupied Eastern territories. It is a version of "cops and robbers", modified to "Nazis and Jews" or "ghetto policemen and Jews" in which some children dressed up as SS-men or ghetto policemen and sought to round up their playmates for deportation. An eight-year-old of the Vilna ghetto describes the game "Jews and Germans" as follows:

"Part of the children became 'policemen' and part 'German'. The third group was comprised of 'Jews' who were to hide in make-believe bunkers; that is under chairs, tables, in barrels and garbage cans. The highest distinction went to the child who played Kommandant Kitel, the Head of the Gestapo. He was always the strongest boy or girl. If a dressed-up 'policeman' happened to find 'Jewish' children, he handed them over to the 'Germans'."5

Games in general help children to learn about their environments in a playful way. In that sense, the game "Jews and policemen" equally helped the children to reflect their new reality of living in a ghetto and to cope and adjust to the new conditions. According to the Ghettos Fighters House this picture was taken on October 22, 1943. That means it was taken more than a year after the majority of all children in the Lodz ghetto had already been deported. In September 1942, during the "Sperre", the Germans decreed that all children, the elderly and sick were to be deported as they had no "labor value". The rounding up and deportation of children was delegated maliciously by the Germans to the ghetto authority under the leadership of the Judenrat (Jewish council) of Chaim Rumkowski. He used his power to exempt certain children, such as children of policemen, the administration and anyone willing to participate in the rounding up of the ghetto's children. That means that the children who were still present in the ghetto after 1942 were not there by coincidence; they were lucky because they had protekzia, or connections to the elite or to people collaborating with the elite. The children that still lived in the ghetto after the major deportations seemed to have dealt with the surrounding conditions and reality in a playful way by adopting the roles of power relationships they were confronted with on a daily basis.

Ultimately, about 95 per cent of all ghetto inhabitants were murdered during the Holocaust, regardless of their positions in the ghetto and whether or not they were temporarily reprieved.

Bearing Witness to German Atrocities

Among the many pictures that commemorate Jewish life in the ghetto are a few that display public executions and deportations. One of these pictures was taken in 1944 at the railway station of the Lodz ghetto.

The photograph displays a cattle car and a group of people standing in front of it, most of them facing the entrance of the cattle car. Among the people are many uniformed men who can by identified as the ghetto police. They are overseeing the boarding of the train. A few meters away from the group is an SS soldier carrying a gun on his shoulder. The inside of the cattle car remains in complete darkness, and is therefore invisible to the viewer. The entrance of the cattle car is illuminated enough to see a policeman pulling one person inside.

If we look at the framing of the photograph, we realize that the scene is not centered; it is located on the right-hand side of the frame. One person is only partly in the picture on the right, suggesting that there was more going on at the time. There is a black area on the left-hand side and building material in the foreground that is blocking part of the view.

After the war, Henryk Ross described in his testimony at the Eichmann trial the circumstances under which he took the photograph.

"On one occasion, when people with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radegast, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing – on one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures." 6

- 6. 6

The black area at the edge of the image holds significance when combining it with Ross's testimony. It provides the viewer with valuable information about the position of the photographer. It shows us that he had to hide in order to capture the photograph and that his view was limited by the conditions of his hiding place. Ross risked his life to bear witness to what the Nazis tried to conceal, including deportations to death camps.

However, his testimony also provides us with additional information about the captured scene that the photograph itself fails to display. If we connect the picture with his testimony at the Eichmann trial, we understand that those deportations were not peaceful and voluntary. Ross refers to shouting, beatings and even shootings. We don’t see this in the picture, but his testimony adds these details in order for us to gain a more complete picture of the situation.

Further, we see people boarding the train, but we don’t see what happens to them after they enter the train, where the train is destined to go and what happens to the people after they arrive at their destination. Ross's testimony adds that the picture was taken in 1944, and that the train was destined to go to Auschwitz. Thus, if we contextualize the picture and connect it with other documents, such as testimonies, historical accounts and maps, we can gain a better understanding of the situation surrounding the one moment that was captured.

Conclusion

Henryk Ross kept his exceptional collection and catalogued it for future generations in order for them to gain an insight into the suffering that the ghetto inhabitants faced. He clearly risked his life and exposed himself to great dangers when taking documentary material of deportations and hangings. In addition, Ross's collection reveals a different and unfamiliar visual perspective of ghetto life, and it contains important images that can help us gain a deeper historical insight of the complex reality of life in the Lodz ghetto.

For all this, posterity owes Henryk Ross a debt of gratitude.

Perhaps, seventy years after the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto, it is finally time to tell the more complicated story, and to internalize the fact that the ghetto represents a place where all the extremes of human behavior could be found: some of the ghetto inhabitants may have behaved in a way that angers or pains us, but they were human beings in difficult circumstances, struggling to survive like everyone else. In his Foreword to the book of Ross's photographs, published in 2004, Robert Jan van Pelt, an accomplished Holocaust historian, wrote that the pictures of the ghetto elite caused a feeling of apprehension and unexpected annoyance.

“For me, and not only for me, these pictures testify to the uncomfortable fact that, amongst the pauperized and starving mass of ghetto inmates, in the wrenching situation imposed by the Germans, a small minority fared relatively well. […] Two generations after the Germans liquidated the ghetto we are ready for the whole picture, and therefore need every single photograph. […] The differences between the seemingly privileged and the obviously destitute fade in the knowledge that almost all the people caught by [Ross’s] camera were murdered shortly thereafter." 7

Roman Halter, the survivor of the Lodz ghetto mentioned above, agrees. “It’s right to show these pictures,” he says. “Sixty years after the war, we have to express the truth. History is finally being told as it should be.”8

However, analyzing Ross's photographs prove that they - as every historical account - have their limits. We must be critical when viewing photographs – we must remember to put them into context.