Lodz, southwest of Warsaw, was the second largest city in Poland before the war. On the eve of World War II, it maintained a population of 665,000, 34% (about 233,000) of whom were Jewish. Lodz also had a sizable German minority, amounting to 10% of the overall population. Lodz was Poland's textile center and many Jews worked within this industry.

On September 8, 1939, the Germans occupied Lodz. They annexed it to the Reich and renamed it Litzmannstadt (after the German General Karl Litzmann, who had captured the city in World War I). Persecution of Jews began immediately after the occupation of the city. From September 18, 1939, all Jewish-owned enterprises had been taken over by Germans. Jews could no longer use public transportation or leave the city without special permission; they were not allowed to own cars, radios and various other items. Synagogue services were outlawed and Jews were required to keep their shops open on Jewish holidays.

Germans looted Jewish stores and raided private homes with assistance from Polish informants. There were many cases where entire houses were confiscated. In other cases, the Germans stole furniture and valuables from private homes. From the very first days of the German occupation, Jews were seized in the city streets in order to perform odd jobs including hauling heavy loads, providing services in military buildings and clearing the streets of debris that resulted from the shelling of the city. Jewish life outside the home was largely paralyzed by seizures of Jewish men and women for the aforementioned humiliating work. Jews were forced to perform arduous physical labor, irrespective of their age and state of health. The main factor, however, preventing the resumption of normal life and the return to work was anti-Jewish legislation.

Subsequently, a directive was promulgated under which Jewish-owned businesses had to be marked. An order applying to the entire population demanded the hand-over of home radios to ensure that news from the free world could not reach them. From January 1940, Jews were forbidden to travel by train. As trains were the only available means of public transportation, the directive meant that Jews living across a range of places were now totally cut off from each other. This directive was especially harmful to Jewish movements, political parties and organizations whose activities were based on constant contact. Even more damaging were the economic directives. In October, an order was issued forbidding non-Jews to purchase or lease Jewish-owned businesses without a special permit. Consequently, Jewish property-owners could not sell their assets to non-Jews for a realistic price. In November, regulations were issued blocking the bank accounts of Jews; each Jew could receive up to 250 zlotys per week (approximately five to ten U.S. dollars). A Jewish family could possess no more than 2,000 zlotys (less than 100 U.S. dollars) in cash and the rest of the family’s money had to be deposited in the bank.

The first anti-Jewish directives were promulgated in November 1939. One of the most oppressive laws required Jews to wear a badge whenever they left their homes. In the Warthegau, where Lodz was located, this badge was a yellow Star of David (unlike in the Generalgouvernement, where Warsaw was located, where Jews were forced to wear white bands with a Star of David). This mark made Jews conspicuous and visible among the general population, making them ideal victims for German soldiers looking for targets to abuse.

In October 1939, the Germans appointed a Judenrat, which in Lodz was called the Aeltestenrat (Council of Elders) with Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski as its chairman.

The ghetto in Lodz was established on April 30, 1940. It was the second largest ghetto in the German-occupied areas and the one that was most severely insulated from its surroundings and from other ghettos; nobody could get in or out.

The Lodz ghetto is an example of a particularly isolated large ghetto, strictly guarded and segregated from its surroundings. This ghetto was built in a neglected part of the city so as to ensure the seclusion and isolation of the Jewish population within.

The situation of the city of Lodz was unique in other aspects: it was annexed to the Third Reich in October 1939. In May 1940, when the ghetto was established, this fact exacerbated its isolation; it was surrounded by a hostile German population and by numerous Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans living in Poland), whose treatment of the Jews was no better than that of the Nazis.

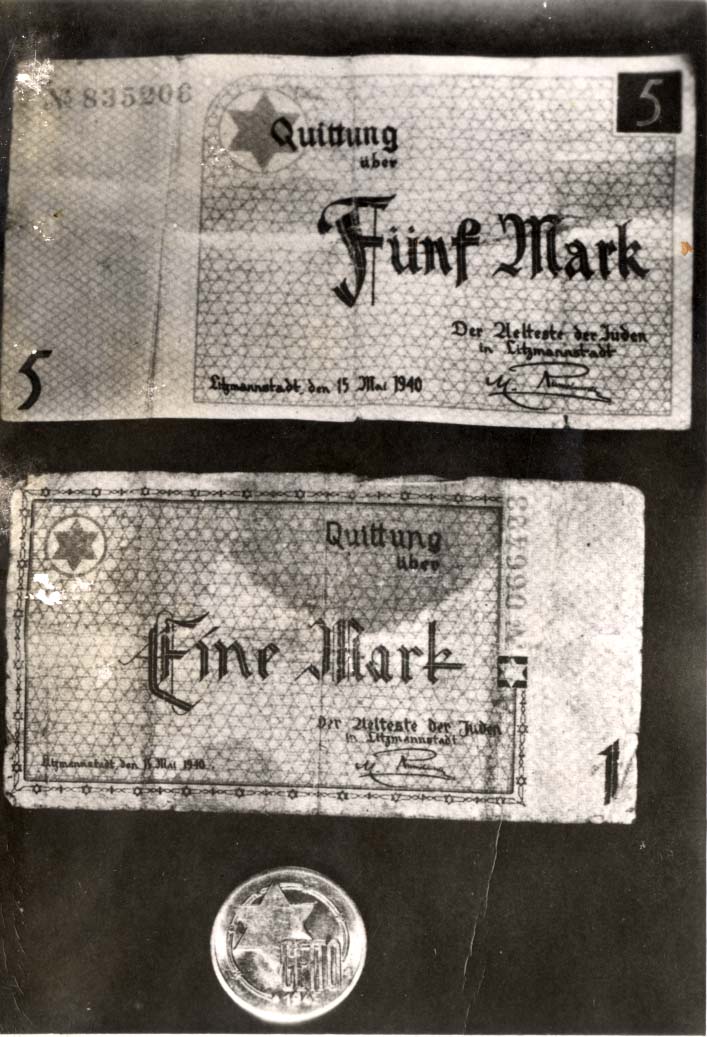

Guards manned the wall around the ghetto very densely. The security in the border area between the ghetto and the city was very stringent and any movement in the area of the ghetto boundary caused the soldiers, SS guards and police to immediately open fire. Even if an inhabitant of the ghetto somehow managed to escape, life outside the walls would have been difficult, if not impossible. The Germans had forced the Jews to give up all the money and valuables they had. Within the ghetto walls special ghetto money was used, which was of course worthless outside.

Some 164,000 Jews were interned there, to whom were added tens of thousands of Jews from the district, other Jews from the Reich, and also Sinti and Roma. The mortality rate was high; epidemics, especially typhus, were rampant. Life in the ghetto was characterized by certain inhuman phenomena which led to the dismantling of the basic frameworks of life. Like in other ghettos, starvation was rife. Some 43,500 people, about 21% of the ghetto population, died of starvation, cold or disease, and the constant hunger, overcrowding, disease and death eroded the very stability of the family unit.

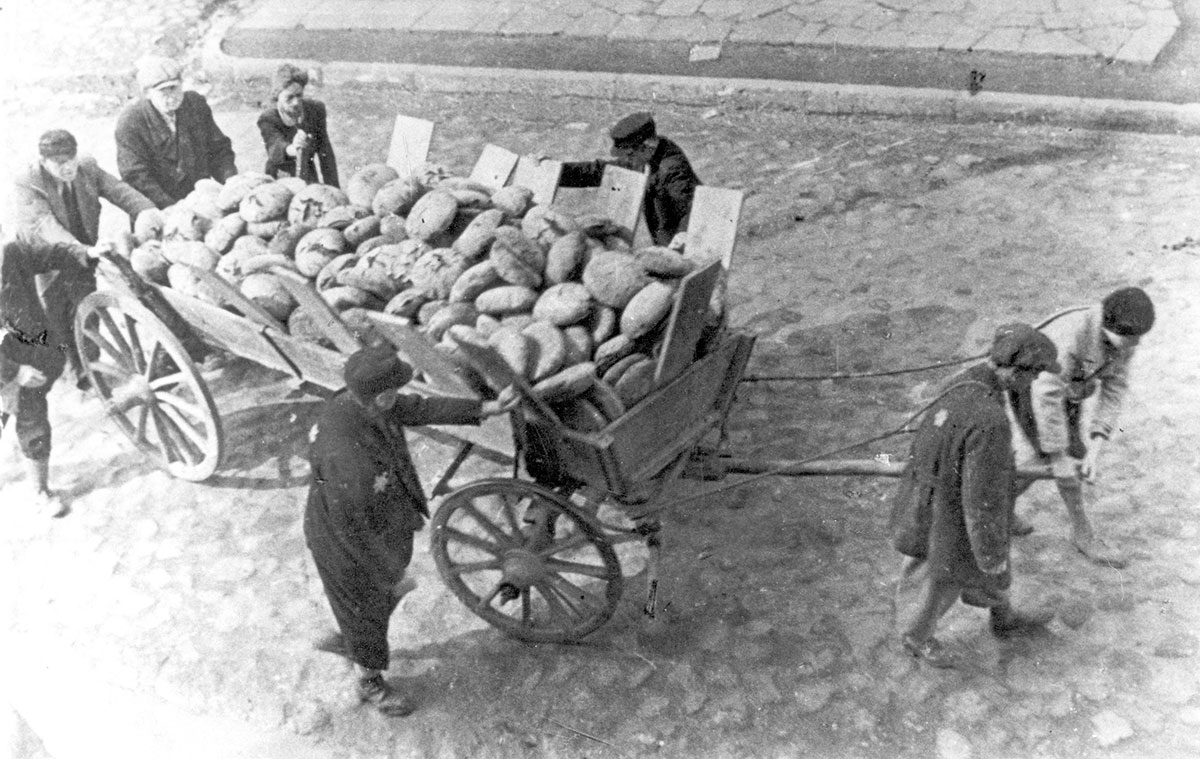

Ghetto inhabitants were required to stand in line for hours on end to receive their family’s food rations. Bread and other food were distributed only once every few days and families were forced to make do with what was distributed until the next food distribution. This policy required careful rationing of the food to all the family members. Mostly, it was the women who divided up the allocated food and hid it away with thoughts of the coming days of deprivation. The hardships of life in the ghetto – especially the hunger – created a great deal of tension in family life.

This is the first page of a journal written by a Jewish youth from the Lodz Ghetto whose identity is unknown. The diary is explored in another article in this newsletter.

“I decided to write a diary; though it is a bit too late […] I committed this week an act which is best able to illustrate to what degree of dehumanization we have been reduced - I finished up my loaf of bread […], so I had to wait till the next Saturday for a new one – I was terribly hungry. I had a prospect of living only from the ressort [factory] soups, which consist of three little potato pieces and two dec. [agrams] of flour. I was lying on Monday morning quite dejectedly in my bed and there was the half of a loaf of bread of my darling sister “present” with me. To cut a long story short, I could not resist the temptation and ate it up totally. After having done this – which is at present a terrible crime – I was overcome by terrible remorse of conscience and by a still greater care for what my little one would eat for the next 5 days. I felt like a miserably helpless criminal […] I suffer terribly by feigning that I don’t know where the bread has gone and I have to tell people that it was stolen by a supposed reckless and pitiless thief. And for keeping up appearance, I have to utter curses and condemnations on the imaginary thief. “I would hang him with my own hands had I come across him” and such like hypocritical phrases […] All I can say is that I shall always suffer on the remembrance of this “noble” deed of mine. And that I shall always condemn myself for being able to become so unblushingly impudent that I shall forever more despise this part of “mankind” who were able to inflict such internal woes on their “co”-human being.“

Although intended to be a temporary transit facility, the ghetto lasted for more than four years after the interests of local Nazis led to a decision to exploit the Jewish labor force.

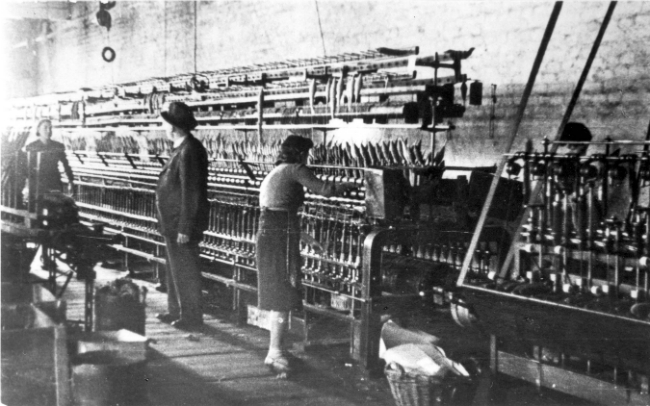

Rumkowski believed that labor would give the Jews an opportunity to go on living and the hope to survive. Thus, he established a multifaceted system in which the Jews of the ghetto worked for the Germans, including “Ressorts” (workshops) that employed even young children. Over 100 factories were established in the ghetto, the majority producing textiles. At a meeting of the Judenrat in February 1941, Rumkowski reported:

[…] I have made it my aim to regulate life in the ghetto at all costs. This aim can be achieved first of all by employment for all. Therefore, my main slogan has been to give work to the greatest possible number of people. It was not a simple matter to set up the workshops. [...] My workshops are already now employing up to 10,000 workers.1

The Germans, however, regarded the ghetto’s output as a mere sideline to the task at hand – extermination.

In January 1942, deportations from Lodz to the Chelmno murder site began, where the Jews were murdered by means of gas vans. Rumkowski was forced to prepare lists of candidates for deportation and organize the rounding up of the Jews. He was unsuccessful in his attempts to lower the quota of Jews for deportation. Between January and May 1942, 54,900 Jews and 5,000 Sinti and Roma (Gypsies), who had been temporarily interned in Lodz, were killed – about one third of the ghetto population. In September 1942, after a temporary cessation, the deportations were resumed for one week. During this one fateful week the Germans hunted down Jews considered unproductive – mainly young children under the age of ten, the sick and the old. This aktion became known as “The Sperre” (an abbreviation of the German word Gehsperre, meaning curfew).

By the end of 1942 almost half of the Jews interned in Lodz had been murdered in Chelmno. Subsequently, the ghetto became predominantly a labor camp. At this stage, forced labor was no longer just a means to fight hunger; it had become a temporary means of avoiding deportations.

In 1944, however, the Germans decided to liquidate the ghetto, and Heinrich Himmler instructed Arthur Greiser, the Nazi chief of the Warthegau to deport the Jews of Lodz to Chelmno and Auschwitz.

On June 23rd, deportations to Chelmno were resumed, and from August 7th, the destination of the transports became Auschwitz-Birkenau. The last transport left the Lodz Ghetto on August 30, 1944. By this time, over 74,000 Jews from Lodz had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On January 19, 1945, the Soviet Army liberated about eight hundred Jews in Lodz.

- 1.Dabrowska D., Dobroszycki L., eds., Kronika Getta Lodzkiego (Lodz Ghetto Chronicle), I (Lodz, 1965), 48.