Liberation

Spring was never as beautiful as in 1945: six years of the most terrible of wars had come to an end; the Nazi regime had been beaten and defeated. Allied soldiers from the West and the East met over the smoking ruins of Berlin. Throughout Europe, people celebrated the victory and the end of the war. On both sides of the line that was soon to be called the “Iron Curtain,” a popular burst of joy and spontaneous brotherhood heralded the end of the nightmare of war, and brought, for a fleeting moment, hope for a new start to humanity.

One people did not share in the general euphoria: the Jews of Europe. They were a party to the war against Hitler, but they were not a party to the victory. For them, victory had come too late: most of European Jewry had been exterminated. The Jewish community in Poland, the largest in Europe, had been almost entirely destroyed: of the 3,500,000 Jews living in Poland before 1939, only 250,000 were still alive, most of them in the Soviet Union; 93 percent had perished. The picture for Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Balkan States was nearly the same. Eastern European Jewry, the center of the Jewish people ever since the expulsion from Spain, had been liquidated in gas chambers. The Jews of Western and Southern Europe also suffered a fatal blow, though the proportion of those exterminated was lower. It is therefore no accident that the survivors make little mention of V-E Day in their awareness of the extent of the tragedy, and the beginning of an almost superhuman effort to pick up the fragments of a shattered life and start anew.

In all of Europe, not counting the Soviet Union, there were at the end of the war about 1,500,000 Jews (the figures are estimates, for no census was taken because of the general chaos), the majority in Rumania, Bulgaria, Hungary, France, Italy and the Low Countries. In Germany itself, there were about 60,000 Jews on V-E Day, most of them prisoners liberated from concentration camps. In Poland, there were about 70,000 Jews; some of them were survivors of the camps, others had gone into hiding during the war or found refuge on the “Aryan side” by means if false papers; there were also surviving ghetto fighters, partisans and other others who had fled to the forests. One by one, they began to emerge from their hiding places and from the forests, to the surprise and annoyance of their Polish and Ukrainian neighbors, who had already taken possession of their homes and property. At the same time, survivors of concentration camps began returning to Poland, in search of home, family, and friends. Each thought that the bitter cup had been his lot alone, and that loved ones had surely been spared. The revelation of the horrors of the Holocaust, the ruins of the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw, the Jewish quarters in cities and towns now emptied of Jews, was a terrifying experience. The homeland of Jews for a thousand years had become a graveyard. The hostility of the populace added to the feeling of terrible tragedy. A struggle was taking place in Poland between the forces of the Right, concentrated around the “Armia Krajowa”, the underground organization affiliated to the Polish government-in-exile in London, and the forces of the Left, concentrated around the temporary government established under the aegis of the Soviet occupation authorities in Lublin. The Jews were considered allies of the Left. The majority of the Polish populace did not particularly care for the Russian occupation, which superseded the Nazi occupation. The Catholic Church had its reservations as well. The only ones who greeted the Red Army with undiminished joy were the Jews, who viewed it as their savior. Before long, not a few occupied respectable positions in the new regime, which regarded them as a loyal contingent in a hostile population. The traditional antisemitism of the Poles and the Ukrainians, which had received legitimation and encouragement during the period of the Nazi regime, now found a new ideological justification. In addition, they feared losing the economic benefits gained by looting the Jews’ property. Antisemitism was further abetted by the general insecurity that prevailed in the chaos of the transition period. Gangs of Ukrainian nationalists rampaged through the country, torturing and murdering Jews and Communists. Traveling by train meant endangering one’s life. Jews who journeyed to their home town in search of relatives or information about their fate were sometimes attacked and murdered on their way or upon arrival, by their ex-neighbors. In Poland more than 500 Jews were killed during the first year after liberation (November 1944 to October 1945), while the government was too weak to prevent the carnage. Before 1947, the Communist government exercised full control only in the large cities; in the rest of the country lawlessness reigned.

Thus for the remnants of Polish Jewry, V-E Day did not bring the relief they had hoped for. Nevertheless, the force of life was stronger that anything else, and the seeds of Jewish life began to develop hesitantly, on a temporary basis and under continuous tension. Emergency relief had to be provided to ensure survival; medical aid had to be administered to the sick; arrangements had to be made for the care of orphans; children had to be taken out of convents and Christian homes which had given them refuge during the Holocaust; schools and other institutions for children had to be organized; and a network had to be set up to help people search for relatives. All these efforts led to the renewal of the Jewish community. The authorities helped them to establish a Central Jewish Committee, under the leadership of Emil Sommerstein. The Committee included Jews loyal to the new regime, who represented the Communist position that Polish Jewry should take part in the rehabilitation of Poland and its reconstruction as a progressive, peace-loving country, along with Zionists like Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman, who saw their function as providing immediate aid and relief for the war refugees.

In June 1945, the repatriation agreement between the Polish and Russian governments, permitting Polish citizens who had taken refuge in the Soviet Union during the war to return to their homeland, went into effect. Most of those affected were Jews. According to various estimates, between 120,000 and 150,000 Jews returned to Poland from Russia. This is much lower than the previous estimates of the number of Jews who survived by flight to the Soviet Union. In many cases, repatriation dashed last hopes held by refugees that their loved ones might have been spared. At the same time, it gave new life to Polish Jewry: the returnees brought with them the appearance of normalcy, with the arrival of whole Jewish families, including children and old people, a phenomenon which had disappeared several years before the Polish scene. The Communist regime devoted considerable effort to rehabilitating the returnees. In Lower Silesia, east of the Oder-Neisse Line, cities, villages and towns were left desolate after the Germans, who had inhabited the area for generations, were expelled in the wake of annexation to Poland. The Jews were invited to settle there and take advantage of the wealth left behind by the Germans. Members of the Jewish section of the Communist Party carried out a propaganda campaign in which they appealed to the survivors to rebuild their lives in Poland, with the help of the new regime. And indeed the urge to live and the desire for security and a normal life pushed them in the direction of Silesia. Community life began to develop, educational and cultural institutions were established, and economic activity was renewed, with the emphasis on productivity, especially in agriculture. For a moment, it seemed as if the situation of Polish Jewry had been stabilized.

The Flight from Poland

However, in the summer of 1946, there was a terrible pogrom, shocking in its cruelty, in the city of Kielce. It took place in broad daylight, under the gaze of the local police (and some say with their participation). Jews who had managed to survive the German occupation now found their death in the city of Kielce and its environs, at the hands of Polish murderers. More that 70 Jews were killed; the government was too weak to prevent the catastrophe. The axe blows in the heads of the Kielce victims reverberated throughout Poland; Jews who had hoped to return and to rebuild their lives in that country experienced a rude awakening. After Kielce, there was no longer any hope for Polish Jewry except in flight. The great “Escape Movement” (bericha) began to take on mass proportions.

The “Escape Movement” started as the spontaneous reaction of activist groups amongst the survivors, who already in the days of German occupation had come to the conclusion that the Holocaust spelled the end of hundreds of years of coexistence between Jews and other inhabitants of Eastern Europe. This was the conclusion of Abba Kovner and the group of surviving fighters from the Vilna Ghetto holding out in the surrounding forests. The same conclusion was reached by a group of Jewish partisans, led by the Lidovsky brothers, hiding in the forests around Rovno, in Volhynia. At the same time that they gave aid to the survivors who began emerging from the forests and other hiding places, these groups made efforts to contact representatives of the Mossad le-Aliyah Bet (the organization which directed the “illegal immigration” to Eretz Israel, usually called the Mossad) in Romania, in order to create a southern escape route to the Mediterranean Sea. Contact was established among the various groups, and soon their activities were centered in Lublin, the seat of the provisional Communist government of Poland. Simultaneously, almost by miracle, contact was made with a third organized and active group of 300-400 halutzim (Zionist pioneers), most of them members of the “Hashomer Hatzair” youth movement and a minority of members of the “Dror” movement. At the outset of the war they had fled to Soviet Asia, with the intention of finding their way to Eretz Israel. This hope did not materialize, but the group was spared the fate of those who remained in Poland and the Baltic States. Their stay in the Soviet Union strengthened and consolidated the group. And now, after sending emissaries to make contact with the Lidovsky and Kovner groups, they hastened to Lublin, driven by the same hope that motivated the other two: to reach Eretz Israel through the southern gates of Poland.

During the same period, in January 1945, leaders of the surviving Warsaw Ghetto fighters arrived in Lublin: Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman, Zivia Lubetkin and Stephan Grayek. Thus it was that the remaining prewar leadership of the Zionist youth movements was concentrated in Lublin. As usual in times of upheaval, the young people took the initiative and assumed responsibility and leadership. The westward and southward movement of Jews began spontaneously, as a result of individuals’ determination not to rebuild their lives on the ruins of the past and the graves of their loved ones. For them, Eretz Israel was not only a land of refuge in which surviving kin might be found, but also the only place in the world where a Jew could control his own fate. The survivors of the Zionist youth movements took over the organization and direction of this spontaneous immigration, believing that the responsibility for the fate of their people was in their hands.

However, disagreements broke out among them: Abba Kovner wanted to direct their steps immediately to Eretz Israel. He had two aims: aliyah (immigration to Eretz Israel) and revenge. Yitzhak Zuckerman, on the other hand, thought that the organization should stay in Poland to organize Jews and help them escape. It was his opinion that Polish Jewry should not be left without leadership; he therefore demanded that the leaders of the youth movements remain in Poland until an alternative leadership cadre should develop. He also rejected the idea of revenge. The “Asians” took the same stand. Abba Kovner’s group continued on its way to Romania, and from there to Italy and Eretz Israel. Antek Zuckerman and his followers stayed in Poland.

At first, the “Escape Movement” consisted of a thin stream of several thousand persons a month, some organized and others not, who crossed the borders of Poland on their way west by three main routes: the northern route – through Stettin, which led to Germany; the southwestern route through Wroclaw, which led mainly to Czechoslovakia, and the southeastern route through Katowicz, which led southward. The movement was basically illegal; it took advantage of the general chaos still prevailing in the country and at its borders. In the period immediately following the war, Europe teemed with the movement of refugees; in the summer of 1945, millions returned to their homes: forced laborers now liberated, refugees who had fled from the terror of the war, captives and prisoners of war. They were joined by eight million Germans expelled from the areas of the Oder-Neisse Line. The news formed a part of this great migration; on the southern route, they disguised themselves as weeks returning to their homeland. At the Czechoslovakian border, they took advantage of the sympathy of the Czechs and the ruling Democratic-Communist Coalition government for the suffering of the Jews. At the Polish border, the “escapees” were subject to the arbitrariness of the border guards, who were often happy to look the other way in return for a watch or a pair of stockings and just as often sent them back to Poland. Whenever official border crossings were crossed, organizers of the “underground railroad” opened alternative routes through mountain passes and along hidden paths; such routes where the going was rough were referred to as “the green border.”

After the Kielce pogrom, the “Escape Movement” changed abruptly. The thin stream became a heavy current and the flight became a semi-legal. In the wake of the pogrom, Yitzhak Zuckerman, who was respected by the Polish authorities – they regarded him as the spokesman of the Polish Communist movement – succeeded in reaching a secret agreement with the Polish Minister of Defense, Marshall Marian Spychalski: in view of the authorities’ inability to cope with antisemitism and to ensure the safety of the Jews, they deemed it preferable to solve the “Jewish Problem” by giving Jews the semi-legal possibility of emigration. It was decided that Jews would be allowed to leave Poland to certain border stations, although to all appearances, it remained illegal to cross the border. This arrangement remained in effect until February 22, 1947, when the border was closed. In the interim, between 75,000 and 100,000 Jews were able to flee Poland.

In an ironic twist of fate, Germany now became a haven for Jews. When Germany was defeated by the Allied forces in 1945, the Western world was shocked and shaken by the revelation of the horrors of the concentration camps. Even though it had heard about the death camps in Eastern Poland, when the latter was liberated by the Red Army, it tended to slough off these reports as products of Soviet propaganda. With the defeat of Germany, the truth had to be faced, and it was worse than any nightmare. The liberated camps held about 60,000 Jews, mere shadows of human beings hovering between life and death. Some of them were already beyond the hope of rescue. At Bergen-Belsen, more than 13,000 Jews died after the camp was liberated, in spite of the devoted care of the Allies’ medical teams, who did everything in their power to save them.

After the first shock of liberation had passed, the dead were buried, the sick hospitalized, and the survivors began to look for their families. Some of them had been cut off for years from the world beyond barbed wire fences and they cherished the hope that their loved ones had been spared. In pursuit of this hope, many joined the “great migration” that took place in Europe in the summer of 1945. Tens of thousands of Jewish survivors returned to their homes. Those from Western Europe, France, Italy and the Low Countries were reabsorbed into their native lands. For them, the odyssey of the Second World War was over. Such was not the case for most of the survivors from Eastern Europe. They soon discovered that the Jewish world they had known was desolated and lost, that their native lands had turned into graveyards for loved ones, and that they themselves were regarded as unwelcome guests. Eastern Europe vomited the Jews from its midst. Bereft of home, family, and country, the survivors turned round and made their way back through Poland to the same camps they had left. At least there they were assured of a morsel of bread and the friendship of others in a similar plight.

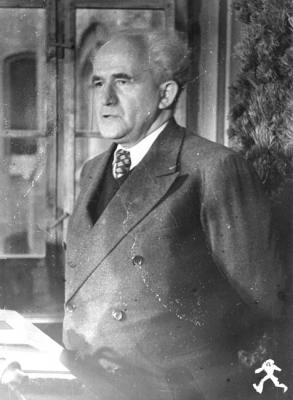

In the fall of 1945, David Ben-Gurion, Chairman of the Executive of the Jewish Agency, made a tour of the camps in Germany. He was received with tears of joy and with a burst of enthusiasm, for the survivors he was a symbol of hope, of the continued existence of the Jewish people, and of the security that leadership arouses among those who feel lost and abandoned. The flag of Zion that he proudly carried and the idea of a Jewish state which he propounded were adopted by the survivors with unbounded love, as a kind of compensation that the world would give them for their suffering. From then on, Eretz Israel would be the last and only safe hope of redemption, and they grabbed onto it with the frenzy of drowning men on the verge of death.

For his part, Ben-Gurion saw the survivors as the great historical opportunity for Zionism. He immediately understood the unique situation that had been created in Germany: under the aegis of the Western occupation forces, especially the Americans, it would be possible to amass Eastern European refugees. These would constitute the most effective weapon in the Zionist struggle. He had already lost hope of Britain changing its Eretz Israel policy, as set down in the White Paper of 1939. During the war, some Zionists had hoped that after the victory Britain would renew its covenant with the Jewish people, open the doors of Eretz Israel to mass immigration, and settle the question of the political status of the country by establishing a Jewish state. Those hopes evaporated when the Labor government came into power in 1945. It became clear that Britain would continue to follow its pro-Arab policy, and that it was determined to separate the question of European Jewry, now focused on the problem of the refugees and the “displaced persons” (DPs), from the question of Eretz Israel. Ben Gurion thought that by increasing American involvment in the question of Eretz Israel, he would be able to create the impetus for changing the status quo. Though the British were victors in the war, they were now in debt to the Americans, beholden to them politically as well as economically, and he hoped through the latter to induce Britain to arrange its policy. It was his belief that the Jewish DPs in the American occupation zone would bring pressure to bear on the American government, so that it would urge Britain to open the doors to Eretz Israel to Jewish immigration. Therefore, even before he returned home, Ben-Gurion instructed Mossad representatives to encourage the flight of Jews from Eastern Europe, to direct them to the American occupation zone in Germany, and, at a later stage, to organize large-scale legal immigration” to Eretz Israel in spite of Britain.

If it had not been for the survivors’ strong will and their readiness to brave the dangers of the “underground railroad”, there would have been no “Escape Movement”. The yishuv (the Jewish community in Eretz Israel) gave this spontaneous movement its organizational skills, its economic sources and the leadership ability of its young people, who had been spared the Holocaust. The combination of the tenacity of the survivors and the determination and devotion of the shelihim (emissaries from Eretz Israel) brought about the consolidation of these unique people’s movement, which will be recorded in the annals of history as one of the forces that brought about the creation of the Jewish state. In 1946, the needs and aspirations of the Jewish refugees agreed with those of the Zionist movement, and from then on the struggle of the homeless for a new life coincided wth the struggle for the establishment of a Jewish state. Miraculously, the 1939 prophecy of Berl Katzenelson was to be fulfilled: “I knew that there were times when even a large state became powerless in the face of the sorrows and suffering of masses of people.”

In the Displaced Persons’ Camps

When Germany was defeated by the Allied forces, about 8,000,000 foreign nationals were living on her soil, most of them forced laborers and prisoners of war. The majority returned to their homes during the summer of 1945. In 1946-1947, about a million displaced persons – those for whom repatriation was considered impossible – still remained in Germany. This population consisted of three main groups: East Europeans who had been torn from their homes by the Nazis and who were afraid to return because of the Soviet conquest and new regime; Nazi liberators, who feared punishment and revenge at the hands of their own people; and Jewish refugees. Jews constituted twenty-five percent of the general population of displaced persons. At the end of the war, Germany and Austria were divided into occupation zones: the British occupation forces were in northern Germany, the French forces in the west, the American forces in the south, and the Russian forces in the east. A small number of Jewish refugees were to be found in the French occupation zone, while more than half of them were located in the British zone in the Bergen-Belsen camp. The second half of 1946 saw increasing movement of refugees from east to west, and at the beginning of 1947, when the number of displaced persons stabilized at 210,000 most of them about 175,000 were in the American zone. This was no accident; rather, it was the result of significant differences n the way the various occupation forces treated the Jewish refugees, differences which developed during the summer of 1945 and became more marked in the course of 1946. Conditions in the camps were improved, food allotments were increased, and regulations were made to assure the smooth running of the camps. These were defined as communities of displaced persons under the protection of the occupation authorities and the direction of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Almost all UNRRA personnel were Jews, and they empathized with the refugees.

The American Joint Distribution Committee and other Jewish philanthropic organizations were instrumental in improving the standard of living in the camps, by providing food, clothing, and by organizing educational and relief services. In the autumn of 1945, the American occupation authorities opened their territories in Germany and Austria to Jewish refugees streaming in from the East. This policy remained in effect through the summer and fall of 1946, in spite of British pressures to change it. The “escapees” were therefore directed to the American zone. In the British occupation zone, they received mush harsher treatment; the British did not regard the problem of Jewish refugees as different from that of other displaced persons, and they refused as a matter of principle to accord the Jews special treatment. As a result, living conditions in the camps located in the British zone were worse than those in the American. The British also limited the entrance of “escapees” into their area.

Two separate organizations were created to represent the survivors of the Holocaust: one in behalf of the refu gees in the American zone, and the other, led by Joseph Rosensaft for the refugees in the Bergen-Belzen camp, in the British zone. In June 1945, the “Central Committee of the Liberated Jews in Germany” was established, with the participation of these two organizations, and in January 1946, the first Congress was held in Munich. No real power was in the hands of the DP bodies, which served mainly in the capacity of public spokesmen; the means for running the camps remained with the UNRRA and the Joint Distribution Committee, which were in no hurry to hand over their authority to the DPs.

“To Live Normal Lives”

Leo Srole, who directed the relief activities of UNRRA at Landsberg, one of the largest DP camps in the American zone, described the refugees in these words: “The Jewish refugees have an almost obsessive desire to live normal lives again.” The phrase is indicative of the mental state of the survivors of the Holocaust. In spite of the limitation, life in the camps was full of vitality and intensity; it was as if the survivors were trying to make up all at once for lost time and lost life. More than anything else, they yearned for human relationships. At first this was manifested in heartrending searches for blood relations. The almost desperate seach for familiar faces endeared to the survivor anyone who had had any connection with his former life: individuals who came from the same town or the same city and even chance acquaintances became close friends. People from the same town grouped together, and the group became a substitute for the lost family. The longing for Jewish faces was so great that a chance acquaintance of two Jews in a faraway train station often turned into a meeting of close friends and partners in fate. Clearly, the same feelings of love that were forged in concentration camps and the death camps now formed the basis for the development of new kinships. Everyone hastened to raise a family. The fact that the refugee camps were generally located in abandoned army barracks with their gigantic halls, which allowed no privacy whatsoever, and their crowded conditions which grew ever worse as the “Escape Movement” increased, did not dampen the desire for the warmth of a family. The birth rate in the camps was among the highest in the world. Even if we take into account the fact that most of the survivors were between the ages of 20 and 40, it is impossible not to be impressed by the outburst of the passion for life and the belief in the future which these survivors of the sword revealed in their readiness for renewed emotional involvement and family responsibility. The child became the symbol of a longed-for normalcy, of the renewal of the chain that had been severed with the annihilation of an entire generation of Jewish children. It was as if a child was the personal contribution of each survivor to the continued existence of the Jewish people.

One of the expressions of the yearning for intimacy was the establishment of the “aliyah kibbutzim”. Before long, those refugees who had been members of youth movements became active again; They organized young people into aliyah collectives, groups which lived together in a commune while engaging in extensive educational activities designed to prepare them for life in Eretz Israel. Their “preparation” consisted primarily of the study of Hebrew and Jewish history, and community work. The kibbutzim became centers of cultural activity lectures, community singing, theater performances and the like. For many young people, bereft of mother and father, cut off from Jewish life for years, the kibbutzim served as a substitute family, a source of friendship and a focus of identity. The educational activities carried out in the framework of the aliya collectives encompassed the refugees who were not members. The dynamic atmosphere of the youth movements, with their optimism and their wholehearted belief in Eretz Israel, helped to resocialize these youngsters, underdeveloped in body and overage in spirit, who now discovered, late, the world of youth.

Most of the inhabitants of the camps longed to return to their studies and their books. They carried out intensive cultural activity: schools and kindergartens were organized, as well as courses for adults, which were called “people’s universities.” A Yeshiva (center for religious studies) was not absent from the scene either. The library was a very important institution in the camps. No matter how many books were sent from Eretz Israel and from the United States, they were not enough to meet the demand. Rabbis serving in the American army contributed books that had been confiscated in Germany. The great variety of newspapers produced reflected the process of reconstruction of Jewish life in the camps and the political involvement of the refugees, as well as the limited education of many of them as a result of the war. Yiddish was the spoken language, and it was sometimes written in Latin script and with Polish spelling. Hebrew was a very popular subject of study as it was considered vital preparation for aliyah (immigration) to Israel.

Soldiers from Eretz Israel

Although no real statistical analyses have been made of the socio-economic status of the survivors in the Holocaust, it is estimated that about 75 percent of the adult population of the DP camps came from the lower middle classes: they were artisans, shopkeepers and merchants. About 20 percent were skilled laborers, and only about 5 percent were members of the upper middle class: managers and professionals. These findings, like the fact that a higher proportion of the survivors were men rather than woman, the absence of children and old people, and the fact that more than 50 percent of the survivor population were between the ages of 17 and 39, reflect the Nazi extermination policy. The intellectuals, the potential leadership of the Jewish people, were destroyed in their entirety. The survivors were left without leadership. While it was true that here and there natural leaders, like Dr. Zalman Greenberg from St. Ottilien, or Joseph Rosensaft from Bergen-Belsen, made their appearance, the refugees generally sought strength and support from the Jews who had not been through the war. For leadership and direction, they looked first and foremost to the Jews of the yishuv of Eretz Israel and to those of the United States. The rabbis serving in the American army had a great influence on the survivors. They had connections with the occupation authorities, and more than once opened up routes for “escapees”, or corrected injustices in the authorities’ treatment of the DPs. But by far the greatest part in organizing the refugees and consolidating them socially and politically was played by the yishuv. The first contact between the survivors of the Holocaust and the yishuv was through the Jewish volunteers from Eretz Israel who served with the British Army. Before long, these soldiers took up the task of looking after the survivors. Long before the Jewish Agency delegation arrived in Germany (they did not succeed in breaking through bureaucratic obstacles thrown in their path by the British until December 1945), the Jewish soldiers were engaged in aid and relief activities; they were the ones who supplied the vehicles, the fuel and the provisions for many “escapees” on their way to the DP camps in Germany, or to the coasts of Italy and France. They were the ones who began to organize homes for children and to take them out of convents and Christian homes. They were the ones who began to organize homes for children and to take them out of convents and Christian homes. They were the ones who began the work of organizing life in the camps. However, their most important contribution was in raising the morale of the refugees: the sight of a soldier with the Star of David on his shoulder was both exciting and moving: it aroused feelings of national pride and identification, feelings sorely needed by the survivors. This was heightened when the representatives of the various welfare organizations began to arrive, and the delegation from Eretz Israel stood out because of its identification with the DPs. Its members came from the same lands as the survivors of the Holocaust. They knew the language and the mentality of the refugees, so that for the latter, communication and attachment came naturally and spontaneously. To that was added the aura of hope wich the name “Eretz Israel” carried with it. It seemed natural that, in the absence of leadership, Jews from Eretz Israel should fulfill that function for the refugees.

Life in the camps was characterized by high tension and by the continuous alternation of hope and despair. The great source of hope was Eretz Israel. The lesson of the Holocaust was that life in the Diaspora was full of danger; there was no way of knowing what the morrow would bring, and therefore the Jews needed a homeland of their own. The feeling that the whole world was against the Jews did not disappear at the end of the war; for the DPs, the Jewish struggle for survival continued. The experience of living in a void, and the impermanence and insecurity of life in the camps strengthened this feeling. Intuitively, the survivors turned to Eretz Israel as the last port, the only hope. This was reinforced by the fact that it was the only land whose inhabitants not only expressed willingness to take in the refugees, but were also engaged in a struggle towards this end. The doors of the United States, Canada and the rest of the countries of the West remained closed to the refugees (only 12,000 of them immigrated to the United States before 1948). Thus, even those refugees who hoped to immigrate eventually to the United States, either through the help of relatives or through other means, identified publicly with the aspirations of the majority to make their home in Eretz Israel and with the demand for a Jewish homeland.

The emotional intensity of the refugees’ lives was also manifested in their political activity. Zionist parties sprung up again overnight. The controversies among them increased involvement in public life. Demonstrations, marches, public gatherings, and political meetings were everyday events. To these was added the influence of the delegation from Eretz Israel and the activity of the “shelihim.” It was no wonder that when the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry and UNRRA took a survey among the refugees (at the beginning of 1946), more than 95 percent expressed the desire to immigrate to Eretz Israel.

As we have noted, life in the camps was characterized by the alternation of hope and desire. The declaration of President Harry Truman, in the summer of 1945, that 100,000 refugees should be allowed to immigrate to Eretz Israel, aroused a wave of enthusiasm. However, when months passed and it became clear that the British were not going to open the gates of Eretz Israel, despair began to set down. The creation of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, the preparations preceding its visit and the anticipation of its decisions caused great excitement in the camps. When the Committee reached the unanimous decision that 100,000 immigration permits should be given to displaced persons in the camps, the refugees were sure that this time redemption was at hand. Again they were to be disappointed; British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin did not heed the recommendations of the committee, and the gates of Eretz Israel remained closed to immigration. Thus two years after V-E Day, the Jewish refugees were still living in transit camps, still unable to settle down and reconstruct their lives. Their frustrations increased and hopes for the future looked dim. True, their lives were not in danger, but they lived on the charity of the UNRRA and the Joint Distribution Committee, and most were unable to work for a living. The work they did in the camps (maintenance, building, repairs) was done on a volunteer basis. They had no desire to become part of the German economy. A black market economy was thriving in Germany at the time, mainly supported by Allied soldiers. Not a few of the DPs took part in it and this harmed the reputation of the survivors with the occupation authorities (who usually turned a blind eye to the involvement of the military in the black market), as well as with the mass media. Among the occupation forces, hostility increased towards the refugees as it decreased towards the Germans. [..] Unlike the non-Jewish refugees, no solution had been found for the Jews, and they continued – as the authorities saw it – to disrupt the pattern of life in Germany, which was gradually returning to normal.

To Eretz Israel

In the stifling, frustrating atmosphere of the camps, “illegal” immigration served as a safety valve and as the last resort. In the “illegal” immigration enterprise, as in the “Escape Movement” from Eastern Europe to Germany and Eretz Israel, private concerns coincided with national ones.

The “illegal” immigration to Eretz Israel, in contrast with the immigration sanctioned by the British authorities by means of immigration permits (“certificates”) began before the outbreak of the war and continued until 1941, and was renewed in 1944. When “escapees” began once again to make their way to the coasts of Italy, where they were met by soldiers from Eretz Israel, Aliyah Bet began to organize an extensive network of “illegal” immigration. The scheme was carried out under the leadership of Shaul Meirov (later called Avigur), who had established the central office of Aliyah Bet in Paris. The political and economic uncertainty in Europe following the war facilitated the creaton of a complex Mossad network in Italy, France, Greece, Bulgaria, Rumania, Yugoslavia and other countries. The network took care of purchasing vessels and equipping them, running the ships, boarding the immigrants and bringing them to Eretz Israel. Mossad representatives sailed with the ships and later commanded them. This network was connected with the “escape” network, and although the two were distinct organizations, both actually operated under the direction of Shaul Meirov, and were in effect two arms of the same body. One was responsible for bringing the immigrants to points of embarkation, and the other for their journey at sea. They were joined by a third organization, the Hagana, which was responsible through the naval unit of the Palmach for escorting the ships and disembarking the immigrants on the shores of Eretz Israel.

The route of “escape” and “illegal” immigration was no pleasure trip; often the refugees crossed the border while the guards looked the other way, either out of sympathy for their plight or because they had been bribed. But in other cases, a border crossing involved the danger of being sent back to the country from which they had fled, or making their way over the mountains through rough and dangerous passes. This fact did not deter families, even those with small infants, from embarking on the perilous journey. When they finally reached the coast, and either went to transit camps or boarded ship to Eretz Israel, they still faced many hardships. Even though the organizers tried their utmost to make it easier for the immigrants, living conditions aboard these ships was terrible. The refugees slept in bunks no more than half a meter wide, one on top of the other. They were crammed together, and sanitary conditions were dreadful; food, and worse, water was limited. Under such conditions, the refugees sailed through calm waters and stormy seas, in the heart of the summer and in the cold of the winter. A few days’ journey often turned into a nightmare lasting several weeks. In spite of these hardships, the DPs fought for the right to board the ships. Thus – after all they had been through – the refugees once again set out with the few belongings they had over their shoulders and undertook the perils of the journey to Eretz Israel. Between 1945 and 1948, 66 “illegal” vessels carrying 70,000 immigrants made their way to Eretz Israel. Of these, 64 sailed from Europe and two from North Africa. After the first successful landings in 1945 and at the beginning of 1946, the British tightened their control of the waterways. They attempted to stop the “Escape Movement” by appealing to the governments of Eastern and Western Europe. These fell on deaf ears - whether for reasons of domestic policy, wanting to “embarrass” Britain in the Middle East, or perhaps simply because of sympathy with the refugees, the countries did not comply. Britain appealed to the governments in control of the ports of embarkation to prevent the “illegal” vessels from sailing, but this also failed. They were left with only one course of action: a naval blockade of the coast of Eretz Israel. And so it happened that the most glorious navy in the world was pitted against the wretched vessels carrying the survivors of the Holocaust. Destroyers with the most sophisticated equipment were recruited for the struggle against the “illegal” immigration. The refugees, with nothing on their side but determination and the readiness to sacrifice, were no match for the British navy. Vessel after vessel was intercepted and brought to the port of Haifa or (after the autumn of 1946) to Cyprus. Once again, the odyssey of the DPs ended behind barbed wire, this time in detention camps in Palestine and Cyprus. More than once, boarding parties intercepting the “illegal” ships fired on and killed refugees crowded together on their decks. After July 29, 1946, the “Black Sabbath” when the united armed struggle of the yishuv in Palestine against the British mandate creased, the “illegal” immiration became the main front in the fight against the British. It was also the only strategy on which there was agreement among all circles of the yishuv and the Zionist movement; the justice of the venture was never a subject of controversy in contrast to armed resistance in Eretz Israel, on which opinion was divided.

In the end, Great Britain could not hold out against the tenacity of the survivors. The “Exodus” affair made it clear that under the political conditions prevailing in the aftermath of the war, Britain was not able to adequately deal with the problem of the DPs. The immigrants on board the “Exodus”, which sailed from Port-de-Bouc and was intercepted near the coast of Eretz Israel, were returned in the British ships to their port of departure. Their refusal to disembark in France, in spite of the suffering they had undergone on the British ships, demonstrated the valor of the weak against the wickedness of a power insensitive to human suffering. When the same power revealed its heartlessness by sending the immigrants back to Germany (to the British zone, where occupation authorities could disembark them by force), the entire civilized world, including citizens of Britain, was shocked by the unequal struggle in which humane justice was defeated by brute force. Three years after the end of the war, the problem of the DPs, the remnants of the Jewish people who survived the Holocaust, continued to trouble the conscience of citizens of Europe and the United States. When the British persisted in their refusal to open the gates of Eretz Israel to the survivors, it became clearer that a Jewish state would have to be created in order to solve the problem. The first to perceive this fact were the Jewish people themselves, foremost among them, members of the American Jewish community. The national awakening of American Jewry, which began after the Holocaust, was reinforced during the three years between the end of the war and the establishment of the State of Israel by the existence and suffering of the DPs and their unrelenting struggle to immigrate to Eretz Israel. The “underground railroad” and the “illegal” immigration operations exposed the American Jewish public daily to the fate of the survivors of the Holocaust, increasing their awareness of the problem. In this way, Jews in the United States as well as in other parts of the Diaspora began to see that the problem of the refugees could be solved only by the establishment of a Jewish State. The “Jewish State in the making” was created on the tracks of the “underground railroad” and on the routes of the “illegal” immigration. More than any other aspect of the flight for independence, the struggle of the refugees brought into relief the common fate of the Jewish people in the Diaspora and in the yishuv, a fate which found concrete expression in the mission of that generation: the creation of a Jewish State.

The Creation of a Jewish State

The British tried to separate the solution to the “Jewish problem” from the solution of the problem of Eretz Israel. They claimed that the problem of the Jewish refugees would be solved by returning them to their homes in Europe and rehabilitating them here. The problem of Eretz Israel was a political question that would have to be solved in accordance with their Middle East policy. Bevin’s approach was based on the denial of the connection between the Holocaust and Eretz Israel. In contrast, the Zionist leadership, headed by David Ben-Gurion, tried to prove the opposite: that the solution to the problem of the survivors of the Holocaust would be found only in Eretz Israel.

[..] After the establishment of the State of Israel, some ten thousand DPs took part in the War of Independence, and many shed blood in defense of their new homeland. When the doors were opened, about two-thirds of the 250,000 survivors chose to immigrate to Israel, despite the hardships, which followed in the wake of independence. One-third chose to reconstruct their lives in Western Europe or overseas. In 1948, changes were made in the immigration regulations of Canada and the United States, enabling a large part of the survivors to find refuge in these countries. Within a few years’ time, the DPs were fully absorbed in the countries in which they settled.

Anita Shapira, Professor of the History of the Jewish People, Dean of Faculty of the Humanities, Tel Aviv University

Irit Keynan, Ph.D in the History of the Jewish People and Director of the Hagana Archives