“Every Jew in France clearly understands that the only thing that can ensure the Hewish people’s salvation is the manly life-or-death fight between us and the Hitlerians. This alone will ensure the survival of the Jewish people […] We must create more and more combat units of the Communist underground. We will attack the enemy wherever it is to be found; we will embitter its life; we will destroy its means of communication and shut down its war machine. We will participate in the daily fighting that will lead to the national uprising.”

(Kolenu, May-June 1943)

The call to go to war through an armed struggle against the Germans, as published in Kolenu, one of the journals of the Jewish Community Resistance, in the spring of 1943, would seem to be a particularly interesting phenomenon. It reflects the complexity of Jewish identity, at least from the Communist angle. We might ostensibly expect that the Communist discourse would be universal in character, addressing the general goals of the Resistance. Yet the short text before us calls for a war to “ensure the survival of the Jewish people” and to take part in the Resistance as part of the national uprising. The Jewish angle appears to have been influenced by the news from Poland about the revolt in the Warsaw Ghetto. What, though, were the circumstances that led the Communists to Jewish discourse? From what Jewish groups did the combatants come? What was the character of this resistance? In this brief historical review, I will try to answer these questions and to present the complex case of the Jewish resistance within the context of the French Resistance.

In general, when discussing the actions of the Resistance, and particularly the Jewish underground movements, it is difficult to distinguish between rescue actions and resistance operations. Unlike Eastern Europe, where the underground movements were usually separated between rescue and resistance, with a few exceptions (such as the family camp of the Bielsky brothers), the perception of Jewish resistance in France was different. The Jewish underground groups worked first of all to rescue Jews, based on the approach that Jewish resistance should first and foremost defend Jewish lives. With the exception of the Jewish Communists, whose operating orders came from Moscow and whose brave resistance actions were directed primarily against German targets, most of the Jewish groups in the Resistance acted to secure Jewish goals.

***

In May 1940 France surrendered to German occupation after a short battle. A month later, France was divided into two areas. The North – the Occupied Zone – was subject to German military rule, while the South – the Free Zone – was under the control of the Vichy government, headed by Marshal Pétain, a hero of the First World War. Naturally, the exacerbation in anti-Jewish legislation and policy was reflected mainly in the North, and initially targeted foreign Jews, those who were not “Israélites” – longstanding French citizens who followed the religion of Moses. This policy heightened the internal tension between the Jewish groups, and it had far-reaching ramifications. Following the deterioration of conditions in the Occupied Zone, many Jews fled to the South in the hope of finding refuge. However, in November 1942 the German occupation was extended over the Free Zone and the situation facing the Jews deteriorated still further. Even before this date, in the spring of 1942, Jews were deported from France to the extermination camps in Eastern Europe – firstly from Drancy near Paris, then from the other detention camps in the Occupied Zone, and, beginning in the summer of 1942, from detention camps in the South as well. By this stage, both foreign and native Jews were being arrested and deported. The deportations were undertaken with the assistance of the French authorities, the police, and the Vichy regime. The testimonies and horrors of the detentions and deportations became known to the French public and were received with shock; the popular reaction enabled the Resistance to expand its operations.

The ‘Résistance,’ as the underground opposition was known in France, was founded in 1940 in response to the German occupation. Its operations were initially confined mainly to disseminating underground newspapers. From 1941, the Resistance acquired broader dimensions and became a phenomenon that may be divided into four stages: The entry of the Soviet Union into the war in 1941, leading the Communists to go underground; the direct links between the Communist movement and the Free France movement; the occupation of the South by the Germans; and the order of “obligatory work service in the Reich” for non-Jewish French people, which was received with anger among the French public.

***

The Resistance Movement in the North – The Occupied Zone

The different character of the regime in the North and South of France influenced the operations of the Jewish resistance in both zones. Generally speaking, until 1942 various rescue organizations were involved in underground actions that focused on assistance to refugees, concealment, and the smuggling of people (mainly children) to the South of France. One of the most prominent organizations established following the occupation by Jewish migrants was based in Paris, on Rue Amelot, after which it was named. Rue Amelot sought to assist migrants and had relatively good access to resources, thanks to its links with UGIF, the official body of French Jews, which was recognized by the authorities. Rue Amelot fully understood the gravity of the situation, particularly as far as migrant Jews were concerned. The organization rapidly adapted to the new situation and operated in an informal manner. Its efforts focused on providing social assistance through soup kitchens and clinics. However, it refrained from underground operations due to concern that this could harm its primary activities. Its policy was to help any Jew who asked for assistance, including financial aid, and did so without imposing bureaucratic questions (contrary to other organizations, particularly UGIF). Following the waves of detentions in the summer of 1942 and threats to imprison the heads of the organization, the offices on Rue Amelot were closed. During the same period, the staff of the organization received certificates from UGIF, thereby enabling the organization to continue its activities. While Rue Amelot had previously operated in a semi-legal manner, it now changed its method of operations and went underground. After the deportations to the East began, the financial support and official status provided by UGIF provided Rue Amelot with tools enabling it to smuggle prisoners out of the camps and move them to the South, with the help of forged documents.

As the situation deteriorated, many children were placed in children’s homes and orphanages in and around Paris that were made available to UGIF. The 400 beds available to the organization were insufficient to cope with the large number of children left unattended and unsupervised following the waves of detentions in Paris in July 1942. Some children managed to escape during the detention operations, others were freed from Drancy, and still others hid with relatives, friends, or neighbors and passers-by who could no longer continue to accommodate them. An absurd situation emerged: since the German authorities were still waiting for instructions from Berlin regarding the handling of the children, UGIF asked that they be placed under its care. Despite the acute need for institutional frameworks for the children, UGIF’s hostels could not provide a solution, since the organization kept lists of the children held in the facilities, and these were revealed to the Germans. Serious difficulties emerged concerning the “blocked children” – 200 children, released from Drancy by the German SD at the request of UGIF, who faced the danger of deportation. Thus, organizations such as OSE, Solidarité, and Rue Amelot faced a new task. Over one thousand children were moved to non-Jewish frameworks, families, or institutions. The Mouvement national contre le racisme (MNCR), whose members were Protestant and Catholic Communists, played a central role in saving the children. In most cases, children were removed from the UGIF hostels by a non-Jewish woman who cared for them for several days until documents confirming their Aryan status were prepared. They were then transferred by members of the MNCR to an adoptive family in a rural area. The smuggling of children and the preparation of the new identity required the involvement of numerous individuals – priests, municipal clerks, and activists in the organizations. Rue Amelot closely monitored the relocated children through regular visits to the families, who were supposed to receive a monthly stipend, although in many cases this was delayed and the payment was not made. Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) transferred hundreds of children to isolated farms in the South, where the children helped to provide for the adoptive families. Their names were encrypted in hidden lists and they were visited occasionally by social workers. These concealment operations received financial assistance from UGIF, and the accounts were forged due to fear of auditing operations. In general, it can be said that the first rescue operations were launched by Jews, while, later on, non-Jews provided support and took enormous risks, acting on humanitarian or religious motives. On more than one occasion, a child was saved thanks to the kindness of a stranger, usually a woman, who was present on the scene by pure chance:

“In July, I was present when the police cruelly dragged Jewish families into three buses. An astonishing sight! […] I knew almost all of them superficially […] One woman gestured to me and asked me to approach: ‘Madame, please, take my little daughter. She won’t be afraid to leave me if she is with you. I don’t want her to stay with me because I have a feeling that we are being led to our death.’ The little girl gave me her hand and came home with me. I did what seemed obvious to me.”

Substantial news of the extermination reached the Resistance at a relatively late point. In November 1942, the Communist organization Solidarité received news that 11,000 Jews had been exterminated by gas in Auschwitz; the information was provided by a Polish Communist in the camp. After much prevarication, the members of the organization published the information, while emphasizing the number of those killed rather than the method used. The members of Rue Amelot found it hard to believe the reports and suspected that they were Communist propaganda. Similar reports had been received earlier, in the summer, by the Consistoire, and probably also by UGIF, but they preferred to keep these silent.

Before moving on to a review of the situation in the South, it is worth noting the difference between the developments in and around Paris and those in the North of France. Not a single Jewish organization maintained a presence in the North, including UGIF. The task of saving Jews was left to the Jews themselves and to those around them. In most cases, help was provided by Catholics, and even more so by Protestants, who themselves had a past of persecution and identified with the Jews. Religious and civil institutions saved Jews, but in many cases private individuals also opened up their hearts and homes. The Resistance movements in the North focused on general goals and did not address the Jewish issue, perhaps because there were few Jewish fighters in their ranks. After the wave of detentions in Paris in the summer of 1943, members of the Jewish Communist group Main d’Oeuvre Immigrée came to reinforce the Communist underground in the North. As elsewhere in France, the underground in the North suffered from losses, and Jews were deported to Eastern Europe.

***

The Resistance Movement in the South – The Free Zone

In 1940, David Knout, an immigrant from Eastern Europe, called for the establishment of a secret fighting organization to unite the Jews and prevent them from becoming the victims of mass murder; he also promoted the goal of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. In January 1942, together with Lucien Lublin, another immigrant and refugee from Eastern Europe, he published the manifesto of the Jewish Army, which constituted a unique Jewish underground movement from the moment it was founded:

“The Jewish people are facing a danger unlike anything it has faced in its long history […] Anti-Semitism has become stronger and more efficient over the past 50 years, to the point that in our day it has become a movement that is international, scientifically organized, and armed beyond all others. Its plan, to annihilate the Jewish people, is already in the stages of implementation.”

It might seem that this manifesto forecasts the future and was ahead of its time, in a manner similar to the proclamation issued by Abba Kovner at the same time, urging members of the youth movements in Vilna not to go like lambs to the slaughter and to oppose the Germans with force. However, there is almost certainly a substantive difference between the manifesto and the proclamation. Historian Asher Cohen argues that, unlike the members of the youth movements and underground in Vilna, the members of the Jewish Army in France did not have any early information about what was happening in the East. Accordingly, their forecast of annihilation was a hunch or ‘poetic license,’ though it was certainly based on an element of logic.

The aspiration of the two young immigrants was realized, albeit after a delay, and the Jewish Army joined the armed struggle in 1943. Its members included activists from the Jewish Scouts and the Zionist Youth. As it began its military actions, the group suffered from a shortage of equipment and connections. However, following the developments in Nice in the same year (see below), the organization proved its ability both to save Jews and to eliminate collaborators through the use of guerrilla warfare. In Nice alone, the Jewish underground lost 45 of its fighters. The organization was also active in the North. Its theaters of operation were chosen for various reasons, including the desire to help and accompany Jews seeking to cross the border into Spain. In June 1944, the Jewish Army became the Fighting Jewish Organization (OJC), and its operation logs provide details about its activities.

The OJC undertook a total of 1,925 operations, including 750 acts of sabotage against railroad infrastructures, leading to the destruction of 705 engines. The activists also destroyed 32 factories that were participating in the occupation’s war effort; 25 more were seriously damaged. Bridges were blown up and collapsed and 152 members of the enemy militia were executed, including General Philippin, a militia member who spied for the Germans. The OJC undertook 175 operations against Germans, in which 1,085 enemy soldiers were killed in battle or executed. The Wehrmacht also lost seven airplanes that were exploded on the ground, 286 trucks, and over two million liters of fuel.

Naturally, not all of the OJC’s operations were successful. More than once its fighters paid with their lives, as in the case of Maurice Loebenberg Cachoud, the commander of the underground, who was also responsible for forging documents for additional underground movements. Cachoud was captured and tortured cruelly before his execution. Unsurprisingly, the most activist organization was that of the Communists, including the FTP-MOI, most of whose members were Jews. This group constituted the major part of the underground in the South. Its units attacked German targets, hotels, means of transportation, vehicle repair shops, and places of entertainment. Although its members were motivated mainly by their Jewish identity and risked their lives bravely, their instructions came from the Communist Party, as noted above. Accordingly, their actions did not specifically target those who were persecuting the Jews (such as individuals responsible for the deportations to Auschwitz). However, the Communists played a crucial role in rescuing Jewish children and engaged in propaganda, urging “every French family to take in one persecuted child.” They also provided guidance to the public on ways to oppose the deportations:

“What can you do not to fall into the hands of the German murderers? What can you do to accelerate their demise and save everyone’s liberty? Here is how every Jew, man or woman, should act […]: Don’t wait at home for the bandits. Use every means possible to hide. As a first step, attend to the children’s safety and hide them with the help of the French population that feels a sense of partnership. To ensure your own safety, join a patriotic organization to fight and strike the bloodthirsty enemy […]. Look for every possible way to escape.”

As mentioned, after the Soviet Union joined the war, the Communists and the other members of the Resistance ostensibly shared a common goal, although the Communists’ actions often led to collective punishments and were the subject of fierce criticism. It is important to emphasize that the Jewish Communists also acted to save Jews, but their actions were first and foremost as Communists. At the beginning of 1943, they were the only element ready to fight among all of the Jewish underground groups in the South. The news of the Warsaw Ghetto revolt became a model and emblem. The Jewish communist newspapers urged people to stop waiting and to engage in forceful resistance to the occupier. They drew inspiration from the uprising, which formed “a link in the historical chain of wars waged by the Jews for the sake of Jewish national existence.” After sustaining numerous detentions over the winter of the same year, the Jewish Communists sought to create Jewish unity. In July 1943, contacts began between the members of the underground movements and political organizations in the South. Communists, Socialists, and Zionists agreed to work together to provide social assistance, but disagreements emerged regarding the armed struggle, stemming from the fear of collective punishment. A compromise was eventually reached and the General Committee for the Defense of the Jews (CGD) was established. It was agreed that the armed groups would not operate under the CGD but that they would receive financial aid. It should be noted that over the course of 1943, the head of UGIF and the head of the Consistoire in the South were arrested and later deported to Auschwitz. This action appears to have encouraged Jewish unity due to the weakening status of the official organizations.

After the Communists lost hundreds of their fighters in the South over the summer, some of their leaders were sent to Paris, where they sought to revive the underground and establish a unified Jewish organization along the lines of the CGD. In order to achieve the desired cooperation, two difficulties had to be overcome: the change in the attitude of the “Israélites” toward immigrants and suspicion about UGIF. In January 1944, unity was achieved in Paris and the United Defense Committee was established, including representatives of the youth movements and organizations representing migrant and veteran Jews, including UGIF. Over the coming months, the SD shut down UGIF’s offices in the South; the organization’s activists, however, continued their rescue operations until the end of the occupation out of concern for the lives of Jews who depended on their help. The Committee’s approach remained unchanged: it was primarily concerned with attending to the wellbeing of Jews, and only secondarily with the armed struggle. In practice, while the Zionist Youth and the Jewish Scouts in the South joined the fighting as part of the Armée Juive, in Paris the Communist organization was left alone in the armed struggle.

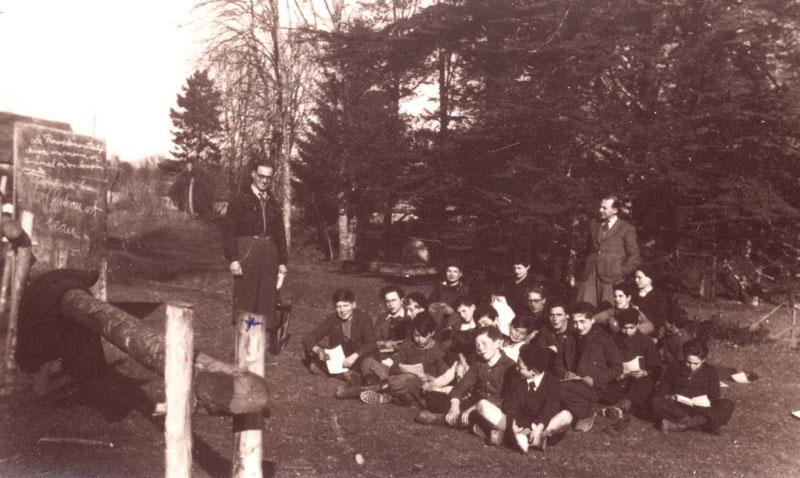

Most of the rescue operations in the South were undertaken by the “networks” and the youth movements. As in Eastern Europe, the transition from a youth movement to an underground movement was far from simple, though the reasons for the crisis in France were different. Until mid-1942, the youth movements focused mainly on education and on consolidating Jewish identity. Their first illegal actions emerged against the background of the arrests and deportations. It could be argued that the idealistic and educational orientation of the movements, which had consolidated over the first few years of the occupation, was an important factor in their readiness to engage in rescue operations at great personal risk. The Jewish Scouts, the Zionist Youth movement, and the Alliance of Religious Pioneers were the most prominent movements in the underground activities. The Jewish Scouts, who formed part of the French Scouting movement and enjoyed state support, regarded France as their homeland and its leaders were members of UGIF. Thus, the members of the movement faced a moral dilemma that was resolved by nature of the reality on the ground, which led to their first illegal actions to rescue children. The cooperation between the organizations continued to develop: they shared information about impending arrests and warned Jews ahead of time. The precedent of the siege at the Winter Velodrome in Paris and the cooperation and sharing of information between the networks and the youth movements facilitated these rescue efforts. Following the deportations to the Netherlands, the activities were intensified. At this stage, the Dutch movement Hechalutz, with the assistance of Dutch underground fighters and members of the Zionist underground in France, began to smuggle children from the Netherlands, through Belgium, to Free France, and then on to Spain or Switzerland. After the Germans took control of the South, the illegal activities of the youth movements centered on the production, use, and distribution of forged documents.

The Church and its clerics played an important role in the rescue operations in the South. Leading figures in the Church cooperated with the underground and were trusted completely. In addition to recruiting Christian institutions – Catholic or Protestant – to help hide Jews (mainly children), bishops and priests also urged their faithful congregants to take part in such activities. In some cases, an entire village would volunteer its help. The best-known example of this is Le chambon sur Lignon, where an underground movement was also active.

Municipal officials or clerks sometimes played a key role in saving Jews in their area, as in the case of Saint Germain de Calberte or Fay sur Lignon.

The networks that worked with the Church were always strictly separated and took extreme cautionary steps in order to protect the lives of the children and those hiding them, but also in order to record the children’s true identity in preparation for liberation. The activists undertook great risks; but the most important and dangerous function was filled by the women who oversaw the children. Their function was to maintain constant contact with the children and to attend to such logistical matters as documents, stipends, and ration cards. Most of the women were young members of the Jewish youth movements, although non-Jewish women from the underground, cooperating with the Jewish underground, were also involved.

In contrast to the concealment operations, which focused mainly on children due to the nature of events, families also crossed the borders with the help of network members and the youth movements. The smugglers relied on help from locals, many of whom were members of the Church. Some of those who helped in these actions did so on their own initiative. The destination varied in accordance with the circumstances: Before the German occupation of Italy, the country was the preferred target of smuggling activities. In some areas, the conditions were so harsh that those fleeing were required to spend two to five days walking across the mountain peaks – something that only young people could withstand.

During the period from November 1942 through September 1943, Nice was under Italian occupation. Many Jews fled to the city, which at one point was home to some 30,000 Jews. The Jewish aid organizations cooperated to alleviate the conditions facing the many refugees, some of whom were dispersed in Italian centers in the area. The youth movements also felt more confident operating in the zone of Italian occupation, and documents prepared by forgers in this area were then smuggled into the German-occupied areas. In September 1943, however, the situation changed. Following the German losses in North Africa, German units arrived in the city, followed by the Gestapo, and Nice thus became a cruel trap for the local Jews and the refugees. The French police in Nice refused to cooperate with the deportations, such that the Gestapo hunted veteran and migrant Jews with the help of local collaborations (“physiognomistes”). At a certain stage Nice was encircled and the Gestapo controlled access to and from the city. Nevertheless, thousands of Jews managed to march to Italy, despite the risks involved. Many of those who escaped were arrested at railroad stations or on buses. Unlike the legal Jewish organizations (such as UGIF), whose actions were constrained, the youth movements continued to provide assistance and forged documents on an enormous scale. In addition to their involvement in the rescue operations, young Jewish members also took up arms, assassinating collaborators and informers and attacking their leaders, thereby

leading to a decline in the scale of such collaboration. The Germans eventually managed to capture around 2,000 Jews, all of whom were transferred to Drancy and then on to Auschwitz. Nice is an example of the ineffectiveness of the persecutors in the face of an efficient Jewish underground, which operated in the city on the broadest and most successful scale seen in France.

Following the Normandy landing, France became a battlefield. In addition to the Armée Juive, other Jewish organizations took part in the battles as distinct Jewish groups, including the Communist FTP-MOI and Solidarité. In the South, Jewish units also joined the rebel forces and helped carry out attacks against the occupying army in Lyon, Toulouse, Marseille, and Grenoble. Many of the Jewish fighters were foreign Jews who fought bravely and heroically in the South and even in the North. In February 1944, the Germans executed the ‘Group of 23’ in Paris – Resistance activists who were arrested. Of the 23 fighters executed, 12 were Jews, all of them migrants.

One of the broadsheets published in March 1944 by the Union of Jews for Resistance and Aid reflects a trend that expanded and intensified as liberation approached. After the Jews had been isolated and excluded from broader French society through terror and violence, they sought, in their publications, to emphasize their contribution to the national struggle for liberation, recalling the splendid relations between Jews and French since the French Revolution. At the same time, it appears that they exempted the French people from liability for the crimes committed by its leaders. As the historian Renée Poznansky notes, this position would later change. Above all, however, they sought to present a united Jewish front to French society – one that sought to maintain the internal unity it had consolidated after years of mistrust and fierce arguments between “Israélites” and immigrants. This unity reflected a substantive change in the Jewish community. It continued after the Holocaust under the auspices of the Representative Council of the Jewish Institutions of France (CRIF), whose origins lie in the united Jewish front that emerged toward the end of the war:

“Yes, Jews – French and migrant alike – are fighting shoulder to shoulder with the entire French people and took part in the liberation of France. […] Within the broad context of the French Resistance, they may perhaps constitute only a modest sub-group […], but they are doing their duty and they are doing so fully. As Frenchmen, they are setting an example to their immigrant brethren, repaying their debt of gratitude. […] The blood of the Jewish

fighters spilled on the soil of France mingles every day with the generous blood of the best sons of the French nation […]. Thanks to this partnership of sacrifice, this partnership of struggle by all the oppressed against the cruel tyrant that oppresses the nations and all free people, a new land will be born tomorrow – a land that will once again be a land of liberty that shines for the whole world; a land that ensures the equal rights of all its children.”