- Nathan Rapoport (1911-1987), born in Warsaw, Poland, was a Jewish sculptor. In 1939 he escaped the Nazi occupation of Poland, spending the war years in the Soviet Union. At the war's end, he returned to Warsaw to study in the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. In 1950, he moved to New York, where he lived and worked until his death in 1987.

Bravery. Sacrifice. Towering heroism. These are the lofty words that the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising memorial elicits from those who view it, either in Warsaw or at Yad Vashem. The work is a monumental tribute to the bravery and spirit of the Jewish ghetto fighters who audaciously and against all odds stood up to the Nazis in April and May 1943, in an unprecedented uprising.

The memorial, created by Nathan Rapoport1 in 1948, and originally erected amidst the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto, is a product of its time: from the enormous chasm of postwar loss and chaos, from the shock and mourning of those who remained alive, there arose a desperate and immediate need to pay tribute to those who managed to fight back. Their bravery needed to be immortalized, captured in stone in order to provide a testimony that – despite claims to the opposite – the Jews did fight back and did not just meekly go like "lambs to the slaughter" to the death camps and killing pits.

By studying the memorial in Warsaw, and its almost identical copy in Yad Vashem, an informed viewer can appreciate the shift Holocaust commemoration has taken over the years. To understand this shift, we can analyze the two parts of this memorial in light of the era in which they were created and the need they fulfilled then – as compared to today's understanding of the Holocaust and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 70 years later.

- 1. 1

The Uprising

The memorial to the uprising depicts a tableau of seven figures, gathered around the central figure of Mordecai Anielewicz, one it's leaders. Anielewicz's head is held high, his set expression both sorrowful and determined. Of the seven, his is the only gaze that stares into the square in front of him, drawing the viewer in to come and bear witness. He appears to be striding forward, his naked upper torso covered by a cape-like coat. Although clearly emaciated and wounded (his head and right arm are bandaged), his arms and neck remain muscular, his presence is powerful and commanding. He grips a grenade tightly in his hand – despite his wounds, he carries on fighting. Framing him are three fighters bearing arms, two of whom are looking determinedly off into the distance. Their youthfulness is sharply contrasted by the bearded figure kneeling at Anielewicz's feet. This figure seems to be influenced by classical Greek sculpture – the fighter's muscular arm, hand and torso contrasting sharply with his aged face, balding head and patriarchal beard. A fallen fighter lies in the foreground at Anielewicz's feet. In the upper part of the scene a firestorm swirls, threatening to consume a mother and child. With their hands upheld in an almost theatrical gesture of despair, these two victims are on the verge of being swept away. As one's eyes rove around this sculpture and take in these other six figures, they always come to rest yet again on the central figure of Anielewicz.

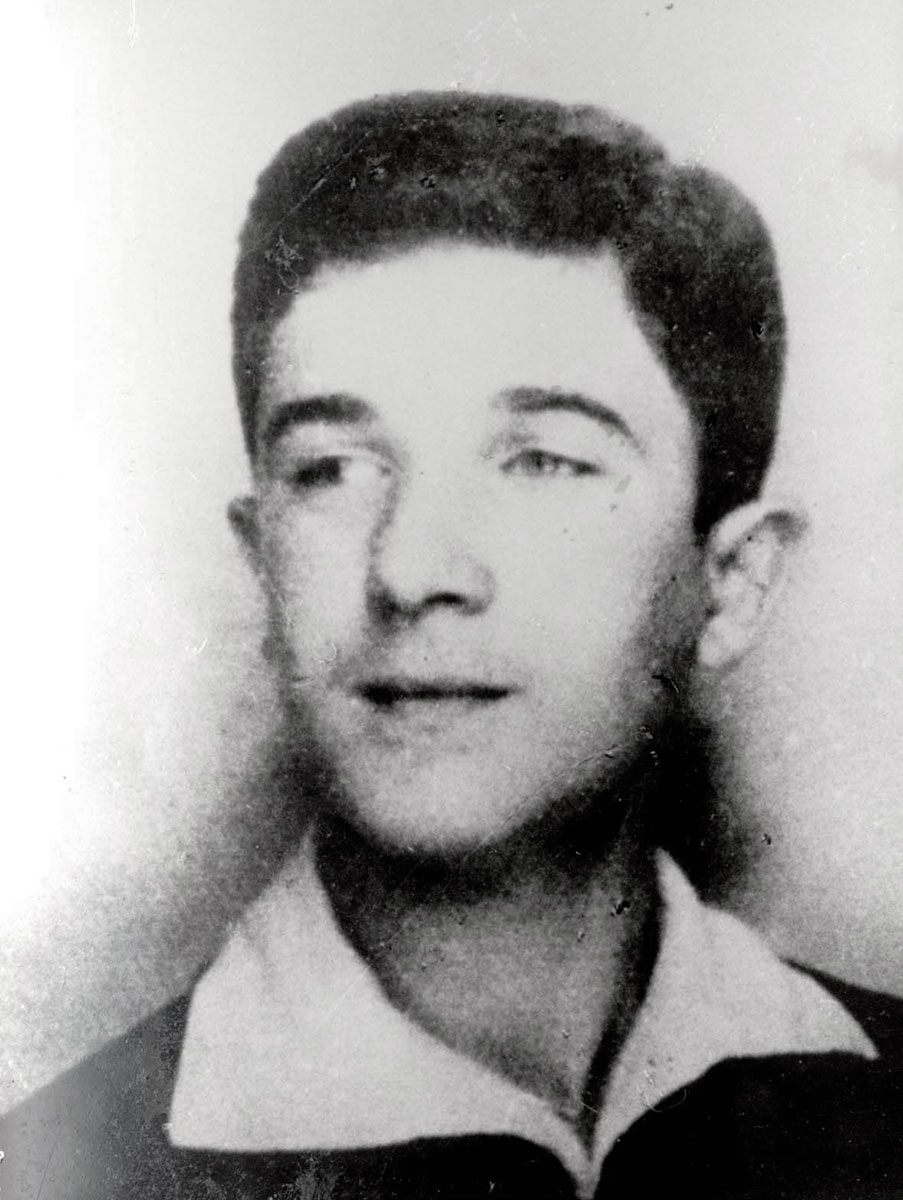

Rapoport felt compelled to portray his Anielewicz as a man of monumental proportions and strength – a rather different depiction of the man than how he actually looked. If in 1948, Rapoport's sculpture was meant to serve as a roadmap for present and future commemoration of the uprising, then the figure of Anielewicz had to be portrayed as a mythical one, embodying the entire ideal of Jewish heroism and sacrifice.

The symbolism and place of the other figures raises some questions with todays' viewers.

This uprising was a youthful undertaking, organized and carried out by the youth movements and young people of the ghetto. Anielewicz, who commanded the ZOB (Jewish Fighting Organization) group of fighters, was only twenty-four years old at his death. Perhaps the kneeling elderly figure in the foreground acknowledges this new leadership role of youth as opposed to the elders of the ghetto?

Another question that can be asked is of the representation of women in this sculpture. The only obvious female in the memorial is the passive figure with the child standing behind Anielewicz. In the Warsaw version of the sculpture, her prominently exposed breast, while perhaps symbolizing the destruction of motherhood (i.e., the inability to nurse), seems to unnecessarily sexualize her. This detail has been covered up by clothing in the more modest version at Yad Vashem.

However, Rapoport's representation of this lone woman as a passive victim is a disingenuous one. In fact, women had an active role in both the uprising and in the highly dangerous role of inter-ghetto couriers. To represent women here not as fighters but merely as passive objects is to do a great disservice to those valiant women fighters and their sacrifices during the uprising. In 1948, when the sculpture was unveiled, Holocaust research and documentation was still new – it would not be until 1984 that "women in the Holocaust" came to be regarded as its own field of research. Perhaps a memorial to the ghetto uprising done in a similar style today would give women the more prominent place they earned and deserved.

Lambs to the Slaughter or Spiritual Resistance?

The monumental scale of the memorial leaves no doubt of the importance armed resistance had in the mind of its sculptor. However, in Warsaw, unlike in Jerusalem, the memorial is two-sided and freestanding. The depiction of the uprising faces a large square and the brand new Museum of the History of Polish Jews. However, unless one ventures to the other side of the memorial – the side facing the street and the block of apartment buildings beyond – one can easily miss Rapoport's tribute to the over 300,000 Jewish men, women and children who suffered and died so horribly in the ghetto and in the gas chambers of Treblinka. Their fate is represented in a much less impactful way than the few who were able to take up arms against their oppressors.

Indeed, this frieze can almost be mistaken as the work of another artist. Instead of the high relief of the front side, this second side is done in bas relief (a much flatter representation). Missing is the frenzied drama and details of the resistance side of the memorial. Here, rather, we see a flat depiction of a mournful group of Jewish people on the final journey to oblivion. They are utterly resigned to their fate; shoulders and heads bowed, the majority of the figures shuffle forward. In the middle of the scene, a patriarchal figure, partially clothed in almost biblical garb, a prayer shawl covering his head, is seen holding a Torah. With his outstretched hand and upturned face, this religious Jew seems to be reaching out to a divine presence, perhaps beseeching God to bear witness to the suffering of His people, perhaps begging for intervention on their behalf. At the head of this procession another bearded Jewish man is represented as powerless and cowed, heavily leaning on a walking stick. What a contrast this resigned figure is to the powerful and determined armed figures on the uprising side of the memorial.

Rapoport continues the contrasts between the two sides by choosing to portray mainly woman and children on the deportation side.

Unlike on the "uprising" side of the memorial, the majority of the figures on this side of the memorial are women, the first of whom is heavily pregnant; her hands are clasped in front of her try to protect a baby who will never have the chance to be born. Next to her, a veiled and stooped grandmother puts her hand on the shoulder of a young girl who leans into her quiet strength.

An elderly woman leads a reluctant a child. This child, as he glances backwards, has the only full frontal facial depiction in the sculpture. When the viewer stands in the right position, he is caught in this child's almost accusatory gaze. What does his baleful look imply? Does it ask the viewer how this was allowed to happen? Does it implicate the viewer as a bystander? Do his eyes implore the viewer not to forget the tragedy depicted here?

If Mordecai Anielewicz embodies heroism, perhaps this child embodies the tragedy of the Holocaust?

Is the fact that there are so few details on the figures depicted on this side of the memorial as opposed to the uprising side an attempt to show that the majority of those murdered will remain forever anonymous, unlike the glorified name of Anielewicz, and those who actively participated in revolt?

Rapoport's depiction of the Nazis in this relief is also an interesting choice. We do not see here brutish figures whipping their Jewish prisoners; indeed, there are no signs of violence whatsoever. The Nazis are depicted as mere helmets and bayonets in the background. Why?

Perhaps the disproportionately small number of Nazi helmets is indicative of the judgmental notion held by some, that the Jews went "like lambs to the slaughter," passively allowing themselves to be murdered. Is this the reason for their relegation to the back of the memorial in the 1948 Warsaw version? Or by merely depicting the helmets of the Nazis rather than their faces, does Rapoport choose to put the focus solely on the Jews and their suffering, unsullied by the presence of their persecutors?

A Current Interpretation Juxtaposed With the Needs of the Past

In the Yad Vashem version of his memorial, the two stories represented by the back and front of the monument in Warsaw are presented side by side. With the perspective of the 70 years that have passed since the uprising, today when we commemorate resistance, heroism and bravery, we are more generous, going beyond the tiny few who were able to actively take up arms and fight. Together with the fighters, we remember other types of resistance – what we today call "spiritual resistance." Perhaps the religious figure with the Torah symbolizes those Jews who were still able to believe in God and practice Jewish ritual in the shadow of death, instilling comfort and faith in the Jews around them, even to the very doors of the gas chambers?

The grandmother's comforting hand on the shoulder of the young girl, and the mother's carefully-wrapped sleeping baby, may represent those families who strove to stay together in the face of an unknown future. Although many families were torn asunder or fell apart, other families found unshakable strength in each other; many adults sacrificed their own food rations to sustain the lives of their children. Some young people who could have escaped the ghetto and attempted to reach the partisans or hide on the "Aryan side" decided to cast their lot with those who had no such option and remained with their beleaguered families unwilling to leave a beloved mother, father, or sibling alone to his or her bitter fate. This quiet resistance is also worthy of note and commemoration, and represents triumph of another kind – triumph of the human spirit, familial and comradely love, devotion to God in a seemingly godless world. These are human ideals the Nazis sought to destroy in the Jews they subjugated and murdered - and yet those ideals still managed to persevere.

Thus in one memorial, we encounter both spiritual and physical resistance. When it was erected in Warsaw in 1948, Rapoport's memorial to the ghetto uprising faced the ruins of one Jewish culture and the promise of a new one in the form of the nascent state of Israel. The heroism of those who were able to fight in the ghetto would now be transferred on to those fighting to prevent another such tragedy in the new Jewish homeland. In 1948, spiritual resistance took a back seat to armed resistance. Today, 70 years later, in the state of Israel at Yad Vashem, they can complement each other, side by side.