- Mendel Grossman, With a Camera in the Ghetto (Lochamei HaGeta’ot: Ghetto Fighters’ House and HaKibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1970), p. 101 (Hebrew).

- Janina Struk, Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence (London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd., 2004), p. 86.

- Grossman, p. 108.

- Arieh Ben-Menahem, “Mendel Grossman – the Photographer of the Lodz Ghetto”, in Mendel Grossman, With a Camera in the Ghetto (Israel: Ghetto Fighter’s House and Kibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1970), p. 101.

- Grossman, p. 103.

- There is one very big difference; Yankush met his death in Auschwitz, while most of the children of the Lodz ghetto, after enduring two years of hunger and deprivation, were murdered in Chelmno during the action known as the “Sperre” in September, 1942.

- Sybil Milton, "The Camera As Weapon: Documentary Photography and the Holocaust," Simon Wiesenthal Musuem of Tolerance Multimedia On-line Learning Center, accessed December 10, 2012.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- "A Film Unfinished," Yael Hersonski, Belfilm, 2009.

- Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History? (New York, London: Penguin Books, 2009), p. 209.

- See, for instance, Yisrael Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939-1943 (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1982), at p. 108: "Some streets, such as Sienna and Chlodna, were considered well-to-do sections. The apartments there were larger, the congestion lighter, and, above all, the people relatively well fed. These streets were the address of the assimilated Jews who had been uprooted from the more exclusive neighborhoods of the capital and rich Jews who had managed to hold on to a portion of their wealth….the most abhorrent and provocative inequality was apparent in the leisure and entertainment spots – cafés, nightclubs, restaurants, buffets – where the members of the new elite indulged themselves to the point of stupor….The April 11, 1941 issue of Gazeta Zydowska carried an advertisement for a café called Tira that promised 'a concert every day,' 'tasty luncheons and portions of lamb,' and a garden by the café'…. Grumblings of protest and bitterness over these manifestations of 'dancing among the corpses' can be found in the ghetto diaries and in the underground press." But, as Gutman (who himself survived the Warsaw ghetto) points out, the Warsaw ghetto was a "deformed society suffering under relentless stress," not a normal society.

- Sybil Milton, “Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto”, in The Warsaw Ghetto in Photographs: 206 Views Made in 1941, ed. Ulrich Keller (New York: Dover Publications, 1984).

- "A Film Unfinished"

- Struk, Photographing the Holocaust, p. 81.

- Ibid, p. 80.

- Struk, Photographing the Holocaust, p. 76.

- Ibid.

- Struk, Photographing the Holocaust, p. 78.

- Struk, Photographing the Holocaust, p. 78.

- Sybil Milton, “Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto.”

In assessing the use of photographs as tools in commemorating the Holocaust, and as historical sources, one of the most important issues that we must be aware of is who the photographer was. Who took the pictures? The photographer, as a human being, may be using his camera to express himself or his views. He may romanticize his subject or treat it with disdain.

In this article, we will compare pictures taken in the ghettos. The first segment deals with pictures taken by Mendel Grossman in Lodz, pictures that were taken with a great deal of empathy. Grossman's pictures were meant to create a visual record of German atrocities, but also to commemorate the victims of these atrocities, including the photographer’s own family. These pictures will be compared with photographs taken in ghettos by German photographers for propaganda purposes, photos intended to depict Jews as hideous, disgusting, immoral and despicable. An exception to this rule are the pictures of Joe Heydecker, also discussed below.

Mendel Grossman

“Mendel takes out his camera. No more flowers, clouds, natures, stills, or landscapes. Amid the horror all around him he has found his destiny: to photograph and leave behind a testimony for all generations about the great tragedy unfolding before his eyes.”1

In the Lodz ghetto, thousands of photographs managed to survive and, in surviving, to commemorate the lives and deaths of the Jews there. Mendel Grossman was already a photographer when the ghetto was sealed in May, 1940, though previously he had photographed beauty and movement. He managed to get a job with the Department of Statistics in the ghetto, photographing “official” subjects such as employees of ghetto factories for the pictures on their work permits, and products made in the ghetto workshops for purposes of attracting German clients. Grossman’s job was the perfect camouflage for his true intention: to secretly record the terrible conditions in the Lodz Ghetto, and the suffering of the Jews there, for posterity. Grossman photographed, as well, the brutality of the Germans. His photography can be said to be photographic commemoration, as well as a form of resistance.

- 1. 1

Grossman was strictly forbidden by Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Lodz Judenrat, to take pictures in the ghetto. On December 8, 1941, Rumkowski wrote to Grossman, “I inform you herewith that you are not allowed to work in your profession for private purposes….Your photographic work is confined only to the activity in the department in which you are employed. You are therefore strictly prohibited to do any photographic work.”2 Much more threatening were the German prohibitions. As the pictures he took – including public executions, deportations to the death camp at Chelmno, and the bloating and misery of the ghetto inhabitants – were damning evidence against the Germans, Grossman could have been killed for taking them. Yet, despite pleas by his family and friends to stop endangering himself, Grossman continued to photograph what he saw in the Lodz ghetto. However, to fool the Germans and the police, he took his pictures in secret. Grossman slashed open the pockets of his coat, and kept his hands hidden inside them. His camera stayed underneath the coat, suspended by a strap around his neck. From his pockets, Grossman was able to manipulate the camera, aim, open his coat slightly, and snap the photographs. In this fashion, he accumulated thousands of pictures that tell us what life was like in the Lodz ghetto.

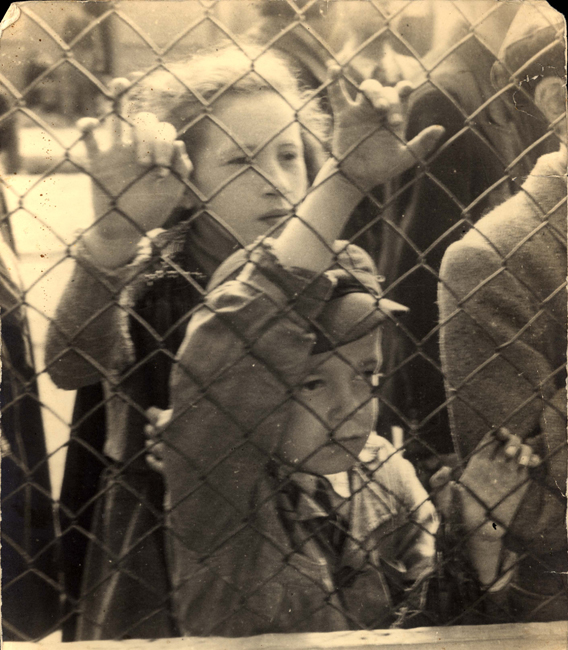

Grossman caught on film the deportations of the Lodz Jews to their deaths at Chelmno – he photographed people writing their last notes to their families, and children waiting behind chain-link fences to be taken to an unknown destination during the "Sperre", the horrifying deportation in September, 1942 where almost all the children under ten years old were taken from the ghetto, and later murdered at Chelmno.

- 2. 2

He photographed deportees from nearby Zdunska Wola who had died anonymously of suffocation in a packed train; Grossman photographed them with numbers on their chests which later appeared on their graves so that their families could identify them. Grossman photographed the inside of the Church of the Virgin Mary in the ghetto, whose altar and saints and huge organ were completely covered with feathers that had been ripped from the pillows and featherbeds stolen from the Jews sent to their deaths. Slashed open by Jewish laborers, the feathers were then cleaned, sorted, packed and shipped to Germany.

He recorded the activities of youth organizations in the ghettos as they met, celebrated, learned about Herzl and spoke of making aliyah to the Land of Israel.

When the Lodz ghetto turned into a de facto labor camp, with over 90% of the population working in German factories, Grossman photographed the Jews in the workshops. He “stalk[ed] the streets of the ghetto, recording on film the agony of the Jewish community of Lodz.”3

- 3. 3

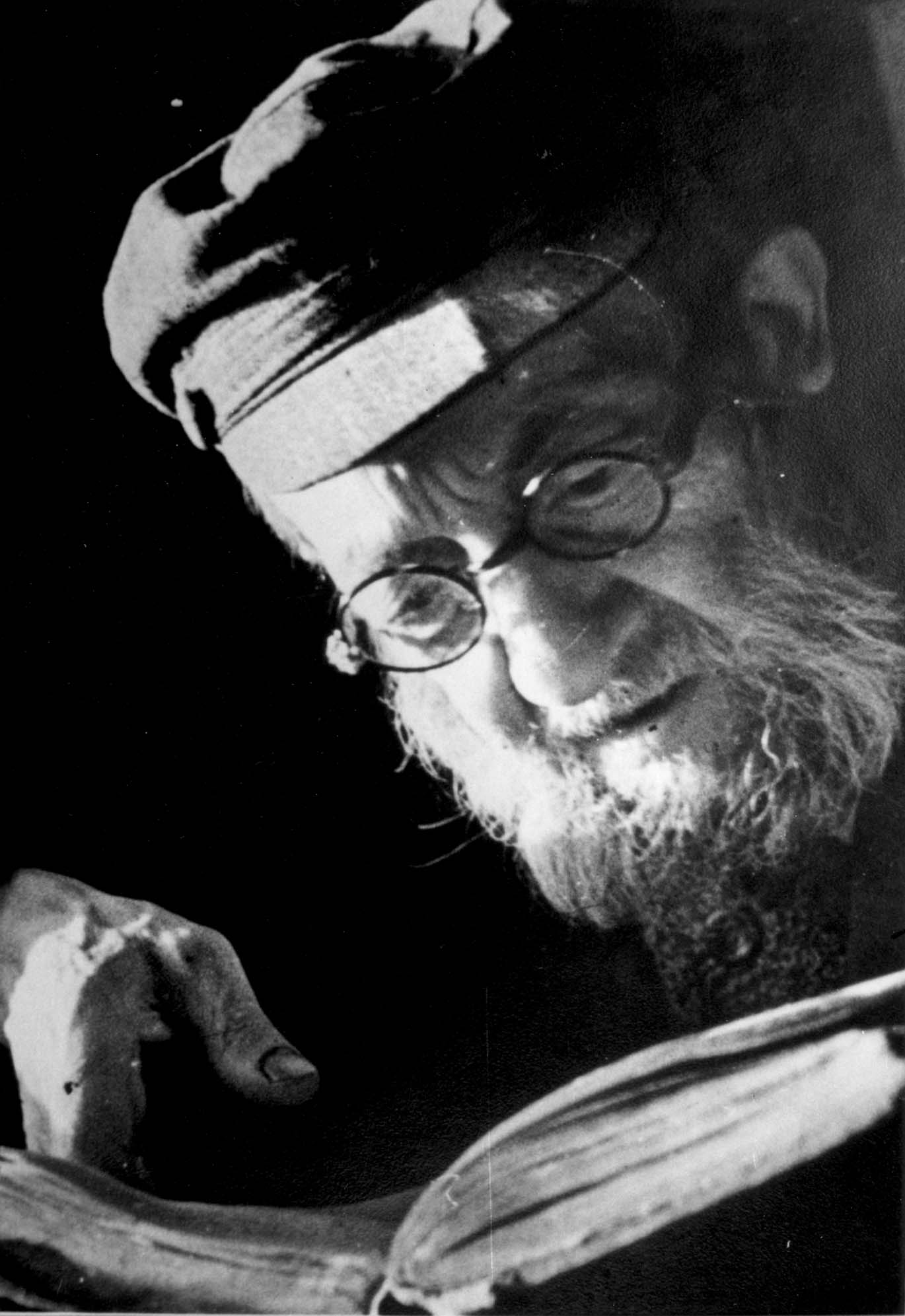

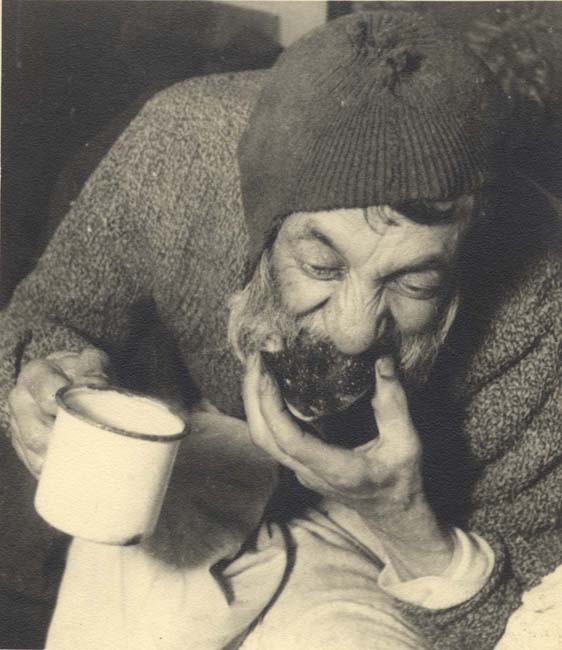

Perhaps Grossman’s most successful photographic record was the one he made of his family. During the four years of the ghetto’s existence, Grossman lived together with his parents, two sisters, brother-in-law and little nephew, Yankush, in a crowded apartment. He watched and photographed his family as they carried on their day-to-day lives, waiting in never-ending lines for whatever food was being distributed, wolfing the food down first at the table, and then later, in bed under blankets, because the cold was so brutal (and perhaps the table had been burned for heat). As he carefully watched his family through the eye of his camera, he saw them slowly fading away. The many pictures he took of his family’s step-by-step deterioration created a horrifying photographic record typical of many other families in the ghetto. Looking at these pictures, the love and tenderness he felt towards his family members is evident. Grossman's brother-in-law was the first in the family to die, on a rainy day after he came home from work. He dropped dead of starvation and exhaustion, wearing the same shabby clothes and wooden clogs in which Grossman had photographed him previously, gulping down soup.4 His father, emaciated and wrapped in a tallit, died as his son stood at his deathbed with his camera, recording his last moments.

- 4. 4

His mother, also photographed, died of starvation.

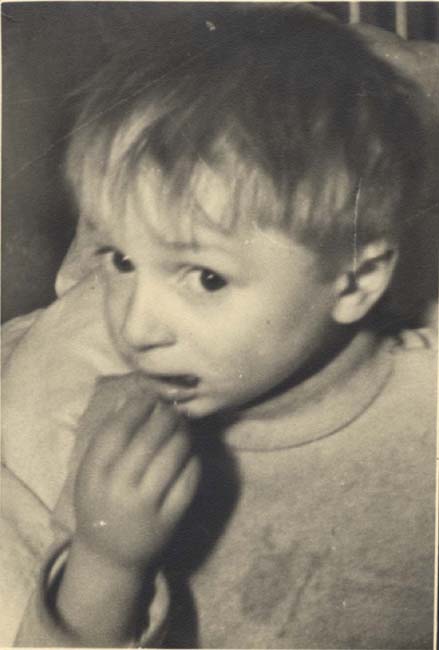

Grossman’s sadness is perhaps most palpable as we watch his the deterioration of his sister’s little son Yakov (Yankush) Freitag, a beautiful little boy.

In the first pictures, a smile plays on his face as he helps his mother with her many chores, including waiting on infinite lines to bring home food.

He was, no doubt, a curious child with an impish smile, well-tended by his mother. Ultimately, however, ghetto life reduced him to a sallow, blank-faced boy, robbed of his childhood and his natural inquisitiveness, deadened somehow. The contrast between the picture where, his eyes closed in delight, Yankush anticipates eating a single cherry brought to him by his uncle, “God knows from where, because nothing of the sort could have been found in the ghetto,"5 and that in which he is pictured sucking on a frozen carrot typical of the spoiled food available in the Lodz ghetto, his eyes full of pain and his hands swollen from the cold, are emblematic of the fate of Jewish children in the ghetto.6

The story of Grossman’s family was typical of Jewish families in the Lodz ghetto, where over 20% of the population was killed by starvation. Grossman, by intensively photographing his loved ones, created a record of his family’s, and the ghetto’s, slow and ineluctable march toward death.

Grossman hid over ten thousand negatives in round tin cans – he gave many of the pictures away to whoever wanted them. He emphasized again and again in conversations with friends that he expected the negatives to reach Israel and to be exhibited as testimony of what took place in the ghetto, proof of this great crime. As the ghetto was being liquidated, he hid the tin cans in a wooden crate in a hollow space he made under the windowsill in his apartment. They were found by Grossman’s sister, Fajge, after the war ended, after Grossman himself had died at the age of 32 on a death march. All ten thousand negatives were indeed sent to Israel, to Kibbutz Nitzanim. However, when the Kibbutz fell into Egyptian hands during the War of Independence, the treasure was lost. Only the prints distributed by Grossman, and some hidden by his friend Nachman Zonabend at the bottom of a well in the ghetto, survived.

German Photographers

Mendel Grossman’s photographs, which show an intimacy with their subjects and were taken candidly, among people who opened themselves up to Grossman and his camera, must be compared to the photographs taken by German photographers in Lodz and in other ghettos, like Warsaw. Official Nazi camera crews and photographers were frequently sent to the ghettos for propaganda purposes; their photographs are clearly meant to show Jews in the worst possible light, to buttress German antisemitic stereotypes.

"The Nazis used photography as part of a sophisticated arsenal of media propaganda to control and intimidate German public opinion…the camera was a weapon…."7 Between 1933 and 1939, Nazi professional photographers photographed over 250,000 images, working for the Reich Press Chamber, a subdivision of Goebbel's Propaganda Ministry.8 Any pride taken by photographers in their work as independent professionals bowed to the brute force and government censorship imposed on them. Once the war started, German photographers and journalists were drafted into the military propaganda divisions of the Army, Navy and Air Force, called "Propaganda Kompanien" (PK). There were seven of these companies, each containing between 120 and 180 men; at their maximum strength, at the height of the German advance in Operation Barbarossa, there were 12,000 men photographing Nazi victories and also documenting the annihilation of the Jews.9

Cinematic manipulation and deception reached a peak in a movie about the Warsaw ghetto made by the Germans and found in the 1950s, together with thousands of other films produced by German film crews, in a concrete vault in a forest in East Germany.10 It had no soundtrack, no credits, and no title, so we can assume that it was not yet finished. There was over an hour's worth of footage, making it the longest film ever made in the Warsaw ghetto. We know when it was made because many of the ghetto diaries found in the Ringelblum Oneg Shabbat archives refer to the photographers filming on the streets and in the apartments of the ghetto; it was made in May, 1942, after the ghetto had already been sealed for 1 1/2 years, and only three months before the first major deportations in which almost 300,000 people living in the ghetto were sent to their deaths at Treblinka. German film crews photographed ghetto inhabitants to create a special kind of propaganda. In the film, the Jews of the ghetto who still had means were juxtaposed with the starving and the beggars, pointing an accusing finger at the Jews for bringing this misfortune upon themselves, as if to say that the rich Jews were so insensitive, immoral and selfish as to have callously failed to provide for their starving brothers. The Nazis wanted to "inscribe for future generations the image of Jews as a depraved and unscrupulous race of subhumans."11 Though we are aware, based on diaries and materials from the Ringelblum Archive, that in the Warsaw ghetto there were rich and poor, and there was a great chasm between these classes,12 the Germans exploited and exaggerated this fact for their own ideological reasons. In reality, the number of wealthy individuals in the ghetto was tiny; the great majority were either starving already, or were about to sink into the depths of starvation and death.

PK Unit 689 stationed in Warsaw in 1941 took staged pictures of the “amusements of the ghetto elite,”13 photographing and filming well-dressed Jews in cafés and in the most luxurious apartments in the ghetto, eating, drinking and having a good time. The footage is remarkable in its cinematic falsification, as it juxtaposes meticulously-staged scenes in which Jews are shown enjoying a life of luxury in the ghetto, with scenes of poverty, starvation and the harshness of life.

Smartly-dressed women step from rickshaws, tipping the driver, while in the next scene a beggar half-clothed in rags performs a frenzied dance before a crowd in the street – one of the children in the crowd is already sprawled out on the ground. While all this misery occurs outside, a woman puts on lipstick in front of an ornate mirror, and then she casually smokes a cigarette. A German photographer named Wist, interviewed in 2009 about the mysterious Nazi film, stated that it was clear to him that the sequences photographed would be used for propaganda against the Jews, since the camera crews were instructed to focus on the extreme differences between rich and poor Jews.14

In some instances, the Germans actually captured powerful-looking men and beautiful women on the streets of the ghetto, and ordered them to strip naked and get into ritual baths, where they were forced to perform lewd acts. Władysław Szpilman, the renowned musician who escaped from the Warsaw ghetto and on whose life the film, “The Pianist” is based, wrote, “The Germans were making these films before they liquidated the ghetto, to give the lie to any disconcerting rumours if news of the action should reach the outside world. They would show how well-off the Jews of Warsaw were – and how immoral and despicable they were too, hence the scenes of Jewish men and women sharing the baths, immodestly stripped naked in front of each other."15

On May 3, 1942, Adam Czerniakow remarked in his diary that a German propaganda crew had arrived that morning to film scenes in his office. They brought in a lit menorah with nine candles ablaze, apparently to make the office look more Jewish.

It is only with the help of Czerniakow's diary that we understand just how far the Germans went in staging these pictures, creating the vision that they desired, even though the Jewish holiday of Hanukah on which the menorah is lit falls out in December, not May. On May 20, Chaim Kaplan noted in his diary, "A few days ago the Nazis came to the cemetery and ordered the Jews to make a circle and do a Hasidic dance around a basket full of naked corpses. This, too they recorded on film."16

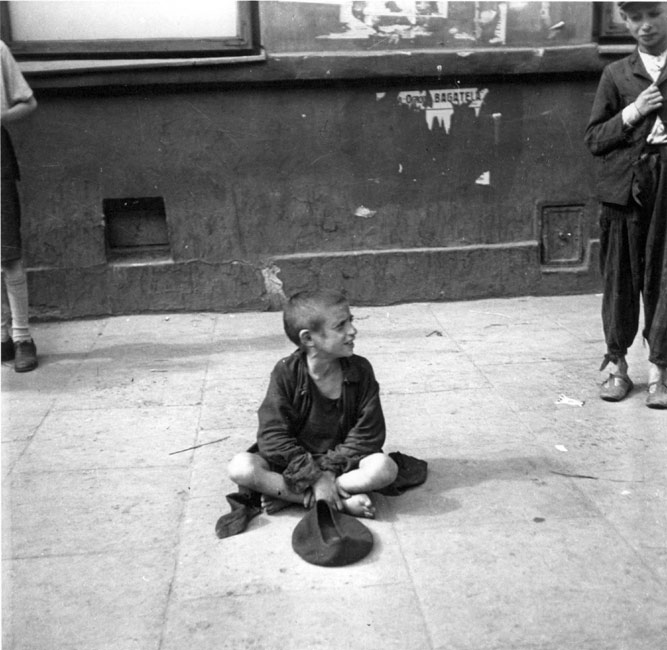

In addition to the official pictures taken by German crews in the ghettos, inquisitive soldiers entered the Warsaw ghetto to photograph the foreign world inside, something that has been called “ghetto tourism.”17 This term was used by Adam Czerniakow, the first head of the Warsaw ghetto's Judenrat, in his diary when he referred to Wehrmacht tourists who were taken on guided tours around the ghetto. These army "tourists" did not see the ghettos as products of the Nazi policy of ghettoization: closing the Jews into restricted areas where food was unavailable, crowding was unbelievable and filth was unmanageable; they saw the ghettos as the natural habitat of the stereotypical Ostjuden they had heard about. The ghetto was a "Baedeker sight with picturesque scenes to be photographed."18 A case that perhaps straddles the line between propaganda and ghetto tourism is that of Sergeant Heinrich Jöst, who treated himself to a “photo-excursion” in the Warsaw ghetto for his 43rd birthday on September 19, 1941. Jöst took over 100 photos in the ghetto with his Rolleiflex camera. Though the photographs were long thought to be private photos taken by a "tourist" who happened to be a soldier, it is possible that Jöst's pictures are actually propaganda; when Russian archives were opened years after the war, a set of Jöst's pictures was found, leading to the conclusion that they were formally sanctioned propaganda photographs. In any event, as we can see, in stark contrast to the photos of Mendel Grossman, above, the pictures are distant from their subjects and show no empathy towards them. They are merely voyeuristic, showing beggars, the sick and the dying,19 without any trace of compassion for their subjects. These Wehrmacht tourists were driven to visit the Warsaw ghetto by “the inescapable whip of horrified fascination.”20

Yet, there were other German photographers who exhibited sympathy towards the Jews. Joe Heydecker, an anti-Nazi and soldier in the German army, stationed with a German propaganda unit in Warsaw, used his 35mm Kine-Exakta, to take over 1,000 private photographs of military life in west and east. But most notable were his images of the Warsaw Ghetto, made in February 1941, which revealed the dreadful conditions there. While the propaganda photographs taken in the ghettos of Europe usually portrayed ghetto inhabitants as dirty, and diseased, by contrast, the photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto taken surreptitiously by Heydecker, a propaganda-company darkroom assistant, showed the terrible conditions in which the Jews were living. Travelling in Europe with his parents before the Second World War, Heydecker had befriended many Jewish families. He had seen the rich Jewish life that existed before the war, and was therefore horrified to see what had befallen the Jews in the ghetto. He entered the ghetto in February 1941 and recorded what he witnessed. It was forbidden to take photographs in the ghetto, but nevertheless Heydecker felt compelled to record what he was witnessing. He explained later, “I felt simultaneously torn by shame, hate and powerlessness.”21 Later, his wife and friends helped to conceal the photographs. Heydecker settled in Brazil in 1960 and exhibited the Warsaw photographs for the first time in São Paulo in 1981.

Conclusion

We must know who took the pictures in order to understand their purpose. Without knowing who took the pictures and under what circumstances, the reality "created" by the pictures becomes very different from the reality on the ground. For instance, if we did not know that the Warsaw ghetto film created by the Nazis was staged, this hour's worth of film could create an incredibly false and dangerous impression about life in the ghetto. If we did not know that the pictures taken by Grossman were pictures of his family slowly fading away from starvation and exhaustion, we might not understand the purpose of commemoration they serve. The conclusion must be that it is very important to be aware of the photographer’s identity and motivations – since the camera is not neutral, the man standing behind it will be able to manipulate it to show his views. Additionally, if the pictures are staged or if their subjects are under duress and are forced to cooperate, a complete fiction may be captured for posterity by the camera.