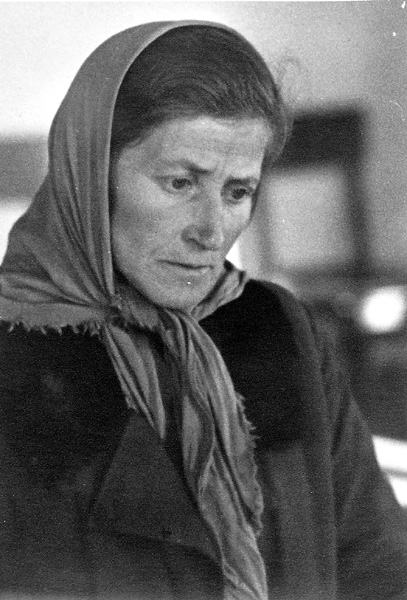

In her autobiography, Ruth Bondy, survivor of Aushwitz-Birkenau, wrote: “In one of the meetings with high school students on Kibbutz Dafna, four of us survivors sat around a table and asked the students what it was about the Holocaust that was most difficult for them to endure. Three male students simultaneously said, ‘the hunger.’ And I said, ‘the filth.’”

As a child, psychologist Shlomo Breznitz was hidden in a monastery with his sister Judith, as his parents were sent to Auschwitz. At the conclusion of his autobiography, he writes, “When my mother perished, one of many victims, I did not take any of her things. My sister Judith and I only kept one item: the dirty and broken comb that she took with her to Auschwitz. She bought it to comb her short hair, in exchange for a full day’s bread ration.”

What constitutes the study of women and the Holocaust? Can such a study be seen as a separate entity when researching the Holocaust? What makes it important? What can we gain from studying it? Following early research that began in the mid-1980s, such questions were often raised – mostly by male researchers – and are still heard today.

The study of the female experience during the Holocaust can be divided into two distinct periods. The first period, which spans until the second half of the 1980s, is known as “the missing phase.” While ample research had been conducted on what was essentially the male experience during the Holocaust, there had not yet been an outlet for the study of their female counterparts.

In an effort to prove that separate study of women in the Holocaust was unwarranted, critics argued that Jewish women were murdered as Jews and not as women. Furthermore, they charged that Nazi racism and the Final Solution did not distinguish between genders, and that there was therefore no place to research women in the Holocaust as a separate chapter in the Holocaust narrative. Such research, they claimed, could distort the overall picture due to the application of modern feminist research approaches that could not have been relevant to the period. In essence, they took issue with the overall feminist approach to Holocaust research.

Proper gender-oriented historiography of the Holocaust began in the second half of the 1980s and continued until the 1990s. This phase was known in relevant literature as the “formative stage”, including pioneering work that paved the way for future research in the field. This research was largely accompanied by the same types of criticism as that of the previous period, and the sections written on the trials and tribulations of women in the Holocaust were closely scrutinized.

Major scholars in the field, such as Joanne Ringelheim, Myrna Goldenberg, Dalia Ofer, Judy Baumel, Marion Kaplan, Carol Rittner and Sybil Milton, have emphasized that their research focuses on the unique female experience during Holocaust, and compensates for a general lack of research in this field. This includes the effects of physiological and sociological characteristics of women on their experience, changes in familial structures, and various responses to the horrific events.

The prevailing phase in current research began at the turn of the millennium. There is now a broader and deeper perspective of research, based on the formative work done on the subject. This broadening perspective, which now includes the female experience, relates even to subjects not yet studied, including the comparison of the female experience in the Holocaust to that of men.

But why study this subject? What do we derive from it that is unique to the study of the Holocaust in general? Is the assertion true that women were murdered as Jews and not as women? It appears to me that questioning this line of research is no longer relevant. Top scholars deal with different aspects of this topic, international conferences and exhibitions are held on the subject, books and studies are published, etc. Through their pioneering work, historians have accomplished their goal; the subject now sits at the heart of Holocaust research.

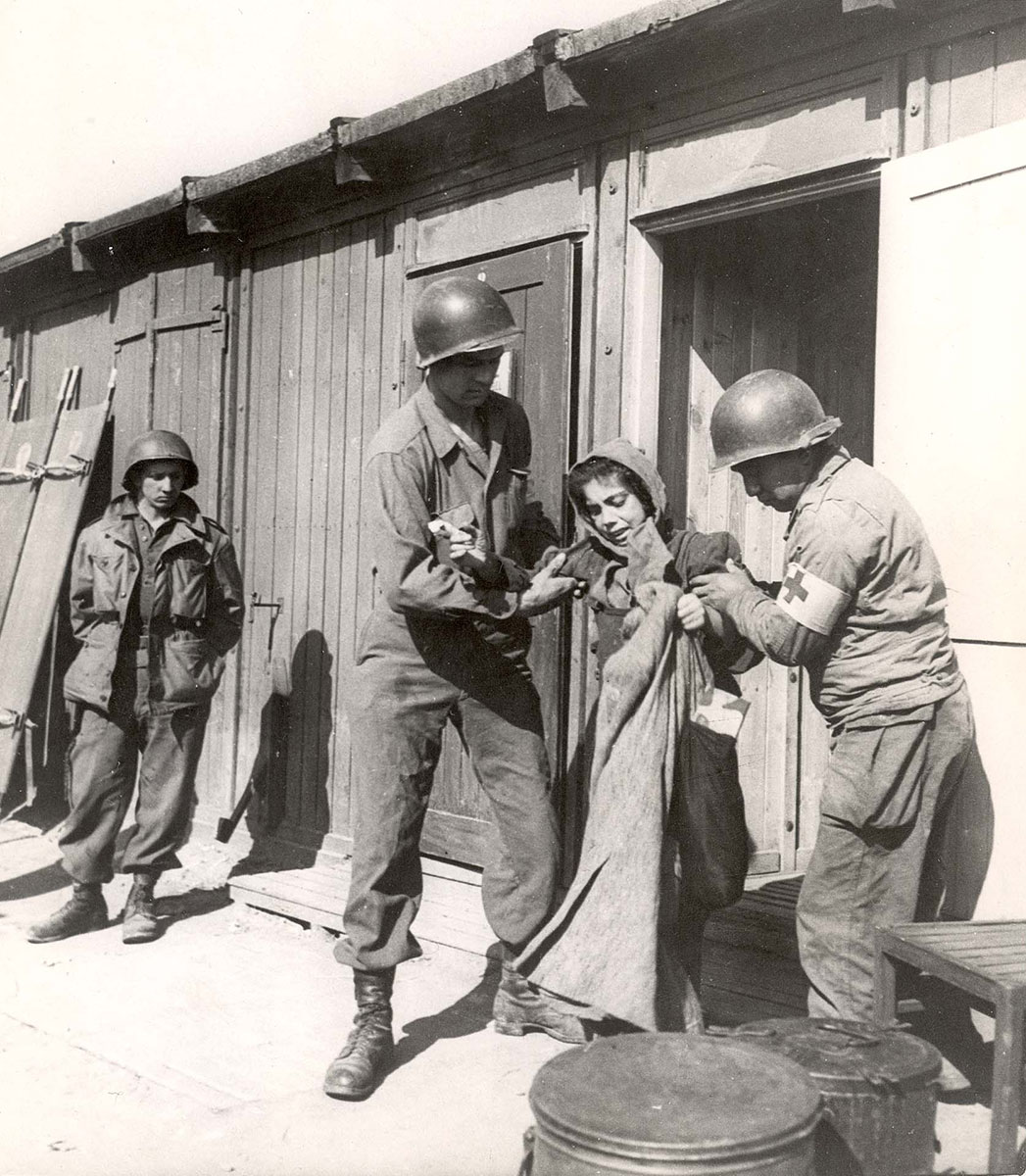

Is it true that women were murdered as Jews? Yes, but they were also murdered as women. And as women, they survived or perished differently than men. Carol Rittner and Joan Roth titled their important book on the subject, Different Voices. Myrna Goldenberg named one of her articles “Different Horrors, Same Hell” because in many cases, women experienced the Holocaust differently from men. It is important to note that we are not only discussing the physiological and essential differences between women and men, or any analysis that would lead to such conclusions. Rather, we are discussing a broad gender-oriented understanding of how men and women experience things, thus moving the focus away from mere physiology.

There is no doubt that part of the unified female experience is physiological, and is connected to certain fears and anxieties of sexual assault, as well as pregnancy and fertility, bringing children into the world and raising them, menstruation, etc. There are nevertheless obvious social and psychological distinctions to be made between the way that women and men experience their lives. These existed almost everywhere and as part of every “event” in the Holocaust: in the ghettos, camps, in hiding, amongst the partisans, etc. Moreover, the chaos of the Holocaust considerably changed the normal way of life that had existed prior to the outbreak of war. For many, essential differences changed the roles of men and women in daily life. According to the work of Professor Gisela Bock, Nazi ideology was not devoid of gender-based distinctions between men and women. This inherently led to a different experience for men and for women, and often – tragically different.

Today, it is difficult to imagine Holocaust research without this crucial facet. The work that continues to be contributed in the field lends a significant layer to our understanding of the Holocaust experience. Absence of this work would leave a void that would overlook over half of its victims, and half its survivors.