Professor Yehuda Bauer speaking at the international conference, The Holocaust, The Survivors, and the State of Israel, 8-11 December 2008

Professor Yehuda Bauer

Professor Yehuda Bauer is Professor Emeritus of History and Holocaust Studies at the Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Academic Advisor to Yad Vashem. He is fluent in Czech, Slovak, German, Hebrew, Yiddish, English, French, and Polish. Professor Bauer was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1926. His family migrated to Israel in 1939. After completing high school in Haifa, he attended Cardiff University in Wales on a British scholarship.

Upon returning to Israel, Professor Bauer joined Kibbutz Shoval and began his graduated studies at Hebrew University. He received his PhD in 1960 for a thesis on the British Mandate of Palestine. The following year, he began teaching at the Institute for Contemporary Jewry at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was the founding editor of the Journal of Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Professor Bauer has written numerous articles and books on the Holocaust and on Genocide. In 1998 he was awarded the Israel Prize, the highest civilian award in Israel, and in 2001 he was elected a member of the Israeli Academy of Science. Professor Bauer has served as advisor to the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research, and as senior advisor to the Swedish Government on the International Forum on Genocide Prevention.

Dr. Chava Baruch

Dr. Chava Baruch is originally from Hungary and migrated to Israel in 1964. She received her B.A. in general history from Tel Aviv University, her M.A. in Jewish Studies, focusing on the Budapest Ghetto, in 1944 from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and her PhD concentrated on the world’s perception of the neological Jews in Budapest between 1919-1943. Dr. Baruch works with educators from Romania, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, the Czech Republic and Slovenia.

For historical background, please see the separate article in this newsletter on Hungary during WWII.

If Hungary had such an antisemitic atmosphere before the war, why did the Final Solution hit it so late?

Professor Yehuda Bauer:

The reason for that is that Hungary was, after all, an independent country and it joined the Germans in the attack on the Soviet Union because of its territorial and international interests. To hand over Hungarian citizens to the Germans was – from a nationalistic point of view – a problem, even when one hated Jews or engaged in antisemitic propaganda and so on.

There was also in Hungary a very clear position of the ruling elite. The ruling elite was not only Horthy, but the Hungarian aristocracy which was partly Catholic, partly Lutheran, partly Calvinistic. They had absorbed into that elite the upper levels of Jewish bourgeoisie. Part of them had converted to Christianity, but part of them had not. And to that Jewish aristocracy there was also an additional social stratum of intellectuals and traders and so on. The elite differentiated between the masses of Hungarian Jewry who were considered to be enemies of Hungarian nationalism and this narrow stratum of top-level Jewish economic leaders.

And it is quite true that Hungary was the only country in Europe where Jews had control of much of the economy of the country before World War I. So there was a social differentiation there. The opponents of the regime from the right within Hungary relied on the massive antisemitism in the Hungarian population, which had existed since the 19th century, and attacked the government from the right demanding more radical steps against the Jews. And these steps were Hungarian steps. In other words, when the Final Solution was developed – because it was not pre-planned, it developed in stages – some of the Hungarian opposition to the conservative regime identified with it and some thought that Hungary should deal with its Jews in a negative way – by itself.

So it is a very complicated issue.

On top of that also is the fact that in 1943 the defeats of the German army at Stalingrad and the surrender of the German army in North Africa (in May 1943) strengthened the tendency in Hungary to seek a separate peace with the Allies. That tendency was there already from 1942. Also, some – not all – but some of the leaders of the conservative elite that was in power, especially the Prime Minister Miklos Kallay who was certainly a Hungarian nationalist, began to doubt the possibilities of a German victory. And it was not a good idea – so he thought – if Hungary was going to seek some kind of separate accommodation with the Allies, to identify with the murder of Jews of which they knew. They did not know details but they had a fairly good idea of what was happening in Poland at that time. Now, this strengthened in 1943.

This is a complicated answer to a simple question.

Dr. Chava Baruch:

Although Hungarian antisemitism was very strong and increased persecution of the Jews, it didn’t become an overwhelming systematic killing policy of the Hungarian Government until 1944. The Final Solution hit the Hungarian Jews when Nazi Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944 towards the end of the war, when most of the European Jews had already been exterminated. But it must be clear that without the close and efficient collaboration of the Hungarian authorities, the Nazis couldn’t have completed this mission in such a short time.

I think we must ask two additional questions: Why were the Hungarian authorities so eager to collaborate with the Nazis in the execution of the Final Solution? and How did the Hungarian Jewry perceive their position in Hungary?

In order to understand Hungarian antisemitism and the perception of the Hungarian Jews themselves in the 20th century, we have to go back to the 19th century, to the so-called “Golden Age” of Hungarian Jewry. Following the emancipation in 1867 by the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef, Hungarian Jews felt that they had achieved their goal of improving their legal status, and hoped for their integration into Hungarian society. This is the key to understanding the Hungarian Jews: they felt and believed that they were Hungarians. They weren't just patriotic - they totally identified themselves with the Hungarian culture, and their loyalty to the state was almost unconditional. Most of them spoke Hungarian and made efforts to completely adopt the Hungarian national culture. Their identity was based on this “double connection”: “We are Hungarians, but we are Jews as well.” Despite the differences between the Neolog Jews, who perceived Judaism mainly as a cultural heritage, and the Orthodox Jews, who insisted on living according to religious tradition, most of the Jews felt part of the Hungarian nation. We have to keep in mind, as well, that only 5% of the Hungarian Jews (who totaled approximately 900,000 at the beginning of the 20th century) were Zionists, and those who followed this ideology, did it much more through a cultural aspect than through political activism. Young Zionists followed information about life in Eretz Israel1, some of them visited the Holy Land as a part of their Jewish heritage, but very few of them left Hungary to settle down in Eretz Israel. This means that we can’t find thousands of young Zionist activists in Zionist organizations (like “hachsarot”2) preparing themselves for a new life in Eretz Israel, as we saw in Poland. Most of the Hungarian Jews didn’t think about leaving Hungary. If you understand this very important point, I think that you can understand how the Jews in Hungary perceived the developments.

We are talking about Hungary between two world wars 1918-1944. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hungary became an independent state and had to face complicated challenges like shaping a new regime, defending the borders of the country, confronting social, and economic difficulties; all this increased radical nationalism and antisemitism.

Now the Hungarians had to redefine the meaning of Hungarian nationality. In other words, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, what did it mean to be Hungarian?

While during the 19th century the Hungarian nationality was based on a liberal approach, now after the war, it was based upon Christianity, which became a kind of precondition to Hungarian national identity. For the Jews this raised an inevitable question, about their further integration into Hungarian society; actually, it undermined the concept of emancipation, which they had achieved in the 19th century. This change had practical consequences in 1920 when the Hungarian government restricted the number of Jewish students in the universities by legislation (“Numerus Clausus”).

It was an intense, troubled time. In one year, between 1918 and 1919, there were two revolutions in Hungary, a democratic revolution and a communist revolution. Because many of the political leaders were of Jewish origin, the communist revolution was perceived as a “Jewish Revolution”, which led to growing antisemitism. The two failed revolutions left a great amount of victims in their wakes, and resulted in Miklós Horthy coming to power.

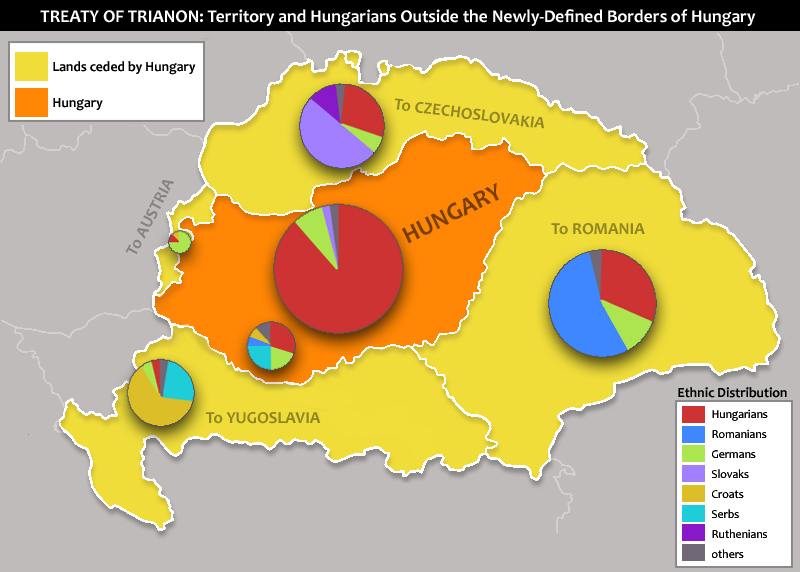

For the Hungarians between the two world wars, the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 was the most painful issue. Hungary had lost most of the territories within its historical borders. A third of Hungarians and almost 170,000 Hungarian Jews found themselves in other countries: Romania, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia. For them it was a terrible national trauma. They dreamed about reconstructing their historical borders.

Who was Miklós Horthy and what kind of regime did he shape between the two world wars?

We have to understand that Horthy wasn’t Mussolini and he wasn’t Hitler. His whole essence was a product of the 19th century Austro-Hungarian Empire. He had been a Navy Admiral. He wasn’t royalty, nor did he come from a royal dynasty, but he created a new kind of aristocracy and declared himself Regent of Hungary; he was the head of the State. There was a parliament, there were political parties, but this wasn't a democracy since all were loyal only to Horthy. On the surface it appeared to be a liberal regime, but in reality it was a very concentrated, very centralistic government - Horthy had power over the army, the police and the gendarmerie (policeman with additional powers). It was not a dictatorship; it was rather a constitutional monarchy without a monarch.

If, in order be a good Hungarian, you had to be Christian, what happens to all those who were not? We have to keep in mind that under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, there were many religious and national minorities: Czechs, Slovaks, Jews, and Croats were living in Hungarian territories as well. But after the Trianon Treaty in 1920, the only “visible” minority in Hungary was the Jews. The Hungarians were searching for a national identity and all of the other minorities belonged to their own countries - the Slovaks were in Slovakia, the Czechoslovakians were in Czechoslovakia, the Croats were in Croatia, etc. – while parts of Hungary were invaded - by the French, by the Romanians. Everyone was confused, everyone was searching for a scapegoat, and as the Jews remained the most visual minority, they became the scapegoat. This was one of the reasons for growing antisemitism. Beginning in the 1920s there was a significant rise in extreme rightist, nationalist ideologies, and a lot of small parties and movements consolidated into a big movement - but it was not like in Germany. There were not yet uniformed units - it was more of a cultural and popular movement that you could see everywhere - in the movies, in literature, among historians; it was in the public discourse. Horthy stopped some leaders of the right, like Szálasi of the Arrow Cross; Szálasi, for instance, was thrown in jail, as were the communists. Despite this, though, the antisemitic movement and the right wing extremists became very strong. The hatred toward the Jews became a generally accepted approach in Hungary.

On the other hand, however, the Hungarian Jews were quite free until 1944. Despite the fact that in 1938, 1940 and 1941, there was antisemitic legislation enacted by the Hungarian Parliament (not the Germans) that actually restricted the Jews in the economic and cultural spheres, and Jewish males were required to report for forced labor, which basically meant slavery in the army, without a weapon, the Jews were still living in their own homes, and they were still quite free. They weren’t marked with yellow stars, there was no starvation, and there were many Jews who escaped from neighboring occupied countries to Hungary. Horthy didn’t open the door to Jews specifically - he opened the door to Polish refugees because there were good relations between Poland and Hungary. Among the Polish refugees were many Jews who found shelter in Hungary. There was quite a difference between the status of the Polish refugees and that of the Jewish refugees, but the Jews were allowed to enter.

So when people ask, “Why didn’t the Hungarian Jews run away?” this question derives from our knowledge about the events that happened later on.

But at that time, why should they have fled Hungary when Jewish refugees were actually coming to Hungary for a safe haven? We are talking now about 1939-1942, so one must not forget what happened at that time in Europe: the Jews in the occupied territories were segregated; in Poland they were starving in the ghettos; from 1941 in the Soviet Union the Final Solution was actually being put into effect; and from 1942 the deportations started to the extermination camps. In the meanwhile, as we can see, most of the Hungarian Jews had relative safety in Hungary despite the anti-Jewish legislation, despite the fact that Jewish men had to serve in forced labor battalions (many of them were sent to the eastern front from 1941 when Hungary joined the Nazi attack on the USSR), and even despite the fact that almost 20,000 Hungarian Jews who were expelled by the Hungarian authorities were killed later on in Kamenets-Podolsk.

The Nazis put pressure on Hungary regarding its Jews, but Hungary remained a partly independent country until 1944. [Hungary was one of the Axis Powers]. So it was quite a complicated and contradictory situation: there was a strong antisemitic approach and policy, but despite all this, Hungarian Jews had a relatively “good life” in Hungary. Even in 1944, they were not occupied like Poland was in 1939. The whole Hungarian government and all of their institutions remained and continued to function even under the so-called German occupation. Yes, the Germans invaded Hungary in a way, but they did not totally occupy it, and the Hungarian government remained partly sovereign.

As for the “reluctance” of the Hungarians to deport their Jewish population, there is a historian who said it best: the Hungarians were keen to get rid of their Jews - but they waited for someone else to do it for them. In 1941, Hungary joined forces with Nazi Germany when they attacked the Soviet Union, and lost one million Hungarian soldiers. This was a very great loss. So from 1943 on, the Hungarian government under Horthy was constantly trying to “jump out” and leave its alliance with the Nazis (this expression comes from the Hungarian word, “kiugrás”). Hitler was aware of those attempts and kept the Hungarians on a tight leash. It was only in 1944 that Horthy left this accord with Germany. This is one of the reasons that the Final Solution reached Hungary so late. The Nazis needed Hungary as the last chance to avoid the collapse of Germany at the end of the war, not just to murder its Jews. The murder was a byproduct – it not the main reason to occupy Hungary. So at this time we are speaking of about 850,000 Jews in Hungary.

What did the Hungarian Jews know or understand regarding the Holocaust?

Professor Yehuda Bauer:

I think the knowledge of what was happening in Poland was quite widespread; contrary to postwar testimonies that argue that [the Hungarian Jews] didn’t know anything. That is totally untrue. People repress what they actually knew. Now, what they knew was not details. But consider the following facts. The Hungarian army was in occupation of areas in the Ukraine where Jews were being murdered. And they used labor battalions recruited from the Jewish population because they were not recruited to go to the army – they were recruited for labor battalions – they were basically canon fodder. [The Jews in these labor battalions] were sent out to clear mines with inadequate equipment and forced to build trenches under impossible conditions. There were exceptions amongst the Hungarian officer corps, people who were less brutal. But the overall picture is pretty grim.

Now, of these Hungarian Jews some 50,000 – 10 percent – came back in 1943 and, of course, they told the stories to everyone. Officers and soldiers of the Hungarian army on leave told their relatives, their friends and sometimes their Jewish friends as well what they saw. It spread. About 2,500 Jews managed to escape from Poland in 1942, 1943 into Hungary. They were living all over Hungary – not only in the large cities, and they told their stories. No one believed them, but they knew the information. They had the information. We have testimonies to prove that. There were some 800,000 radio receivers amongst the Hungarian population. And the story of what was happening to the Jews in Poland was occasionally told. That spread to the Jewish population. Until 1944 the Jews had radio receivers.

Then you have the Slovak Jews, at least 7,000 of whom escaped from Slovakia in 1942. And they had information directly from Poland. And they spread the news. Now, they didn’t know about Auschwitz, nobody knew about Auschwitz. Nobody knew details about Treblinka or Belzec and so on. But they knew that Poland meant death. Now, that information did not become knowledge because when you are threatened with life-endangering information and you have no way to escape the consequences, you tend to repress it. So we have x-number of testimonies that say: “Yes, we heard, they told us, but we didn’t believe them.” I think that is the crucial situation. The idea that somebody would have told them in 1944 something about Poland they didn’t know, stretches the borders of imagination, contrary to what they say. Survivors will tell you and contradict themselves: “We had no idea. Yes, they told us, but we didn’t believe them.”

That is a well-known issue. Epistemology shows that it is a natural human tendency. You receive information, but it doesn’t mean you understand it or you accept it, which would mean that you have knowledge.

Dr. Chava Baruch:

I would like to clarify an important issue. Those Hungarian Jews who survived have been attacked - and they are still being attacked - by people who say how stupid they were for staying in Hungary and not running away, by people who accuse the leadership of not acting in time, etc. I think that there is a big difference between “knowing”, “internalizing”, and “taking action”. It takes time to comprehend a situation. I would like to add some additional questions: Did the Jews know, and what did they know? This is the first question. Who knew about what? The Jews (collectively as a community)? Individual Jews? The Jewish leadership? Horthy? The Hungarian government? If we are looking at those questions, there is a crucial difference between the Jews and the Hungarian authorities. The Hungarian authorities knew everything very well, and they had the power to act. In April 1944, the Auschwitz Protocols (written by Verba and Wetzler) arrived in Hungary. Horthy received those protocols, which described the whole process of extermination in Auschwitz and Birkenau. He stopped the mass deportations at the beginning of July 1944, following the pressure of the President of the U.S. and the Swedish King, but this took place after the deportation of the majority of the Hungarian Jews. Horthy could take action, and he did. This is also a proof of his partial sovereignty under Nazi occupation. But if he could stop the deportations in July 1944, why didn’t he stop them from the beginning? There is a crucial difference between the leaders of a state, and the civilian population in their ability to act, and the Jews, who were the most helpless and had the fewest choices. Even if you knew and heard about something - and probably most heard something, because some had husbands who came back from forced labor, and everybody was talking - this talking was done secretly, behind closed doors. Even the Jewish newspapers published at the time were not openly reporting on what was happening to the Jews. There were hints between the lines, but even when they talked about Germany, they wrote that the German Jews had been “destroyed”. What did they mean by this term? It's unclear whether they really understood that the Jews were being killed. But even if they had understood it - then what? What could they do? What could a family have done? What could a small Zionist movement, which wasn't popular in Hungary, do? And they did try - each of these tried to do something. What did the Jewish leadership try to do? What about the Hungarian authorities? What about the Nazi authorities? We have to take all of these into account and to remember that even in 1944, most of the foreign embassies and diplomats were still working in Budapest. There were many so-called “authorities”. So who knew what? What did they want to do with the information, and what did they do in practice? I can give you an example of what Jewish individuals could have done using a story from my mother's family.

My mother's family was a so-called Orthodox Jewish family. Today I know that my grandfather knew everything, and that he understood that Auschwitz was death. My grandfather was 46 years old, had 7 children and was a widower. From 1943 he knew the situation facing the Jews - and yet he stayed home. And when four of his older children were able to acquire some false papers he encouraged them to run away. (They survived). But he stayed at home with the children who had no papers, and that's why he ultimately was deported to Auschwitz. When his youngest child, 11 year-old Rachel, wanted to escape from deportation, he agreed that she should escape. It was my mother, who was 20 years old at the time, who said, “Father, are you crazy? What are you talking about? How can a lonely little girl face all the dangers around? She is not going anywhere.” Little Rachel cried out and accused my mother: “I will die because of you!” But my mother didn’t understand and my grandfather didn't want to tell her that they were going to be murdered. They arrived at Auschwitz, my grandfather said “Shema Israel”3, and that was it. He arrived with 15 year-old Eliezer, little 11 year-old Rachel, and my mother. Only my mother returned. He knew exactly what fate awaited them. So why didn't he tell them? Facing these circumstances, I understand him, because knowing my mother, I think he did the best that he could do. Had she known that she was going to die, I don't think she could have survived even one hour. I give this example to show: my grandfather knew. So what? What could he have done? He couldn’t fight the Hungarian gendarmes, so he tried to save his children. He was young, he could have run away, but he decided to stay with his children, knowing that he was going to be killed. He encouraged his elder children to run away with false papers, and was ready to let his little girl run away as well, but avoided telling the truth to his eldest daughter. Yes, in a way he scarified himself and his children. This is only one example – my family example, but it truly reflects the terrible dilemma of the Holocaust: you couldn’t save all of the Jews, so you had to decide which of them you were going to try to save.

Using the same approach of examining individual cases, there was the young Zionist movement - many of its young Hungarian members had come from Czechoslovakia and Poland, so they weren't exactly Hungarian Jews, even if they spoke Hungarian. They came from the eastern part of Europe; they were much more attached to their Jewish identities, more willing to rebel against authority. This was a different type of young leadership. Many of them tried to save Jewish lives by distributing false papers that they obtained at great risk. They came to the ghettos, and tried to convince the local Jewish leadership to escape - but those people sent them away! “Go away, otherwise I will go to the authorities and tell them that you are demoralizing the ghetto. I don't believe you, go away, who do you think you are?” So there you have it - even those who knew exactly what was happening and tried to do something to save people couldn't do all they wanted to do. Nonetheless the Zionist underground’s members in Hungary saved the lives of thousands of Jews.

In Hungary, unlike in Poland, there were no ghettos that lasted for three years - in Hungary the ghettos existed only for some short months. The uniqueness of the Hungarian Holocaust is that when the Nazis came in March 1944, they collected all of the Jews in the provinces and started to deport them to their deaths in a mere 56 days. Fifty-six days was all it took - with the tight collaboration of the Hungarian authorities, from the highest levels to the last gendarme. Fifty-six days leaves no time to react - it all happened so fast. There were no well-known local Judenräte (representative leadership) because there was no time - they were sent away. So the Jewish Judenrat was in Budapest. And what did they want to do? Their goal was to at least keep the Jews inside Hungary - not to let them be taken away. That's what they tried to achieve, since they knew about Auschwitz. They tried to save lives. But they couldn't do much. What they tried to do was to at least prepare the Jews for forced labor: “Please pack warm clothes.” It’s terrible, but that was their helpless situation. They felt totally betrayed by the Hungarian authorities, to whom they were loyal for generations. The Hungarian antisemitism became very dangerous when it was allowed by Horthy’s regime, and was encouraged by the Nazis to become a lethal policy.

So where do these accusations about the lack of action by the Judenrat come from?

Well, we have this very nice example of the Warsaw ghetto uprising - which became the model that all of the ghettos and Jewish behavior during the Holocaust were measured by. But a revolt was only possible in certain places. We know the difficulties: how long it took to organize it, and how the fighters had to search to obtain even one gun. In Hungary it all happened in a mere 56 days - there was no Armia Krajowa, there was no real Hungarian underground. There were no partisans in Hungary who could help the Jews to revolt. Most of the young Jewish able-bodied men were far away from their homes in force labor units – who could revolt? Women with children and their elders?

Many of the Hungarian Jews were in the Austro-Hungarian army in WWI and were very proud of their service. I think this is the key to understanding the mentality of the Hungarian Jews: they obeyed laws and saw themselves as loyal, law-abiding citizens. They demanded their rights through the legal systems because that's what they knew, that was their world, that was their belief and that's how they had been raised through the generations. So were they now supposed to act against everything they knew and believed in before? They were unable to change this approach! By the summer of 1944, almost no Jews remained in the provinces. More than 420,000 Jews from the provinces had been deported in 56 days, leaving the last remaining Jews in Budapest. And there, most of the official decrees and instructions were in Hungarian and not German - they came from the Hungarian authorities. (From this you can understand the depth of the collaboration between the Hungarian authorities and the Nazis). In Budapest, in the summer of 1944, the Jews had to move to Jewish houses - and who had to organize the move? The Hungarian police and the Jewish leadership. In 8 days they had to move 200,000 Jews out of their apartments - and they did it. The Jews tried to help each other, they struggled to survive, and some of them tried to save Jewish lives. We expect armed rebellion against the Nazis, but this is not what happened in Hungary, there were no real options to rebel. We have to look at what happened there in real time.

Why has Kasztner become such a codeword? Why is he controversial?

Professor Yehuda Bauer:

Kasztner was never a member of the Hungarian Judenrat. He was the head of a minority group within the Zionist movement in Hungary which itself counted about five percent of Hungarian Jews – a small minority. The vast majority of Hungarian Jews would have nothing to do with Zionism. And the Zionist movement was split – as usual.

Kasztner’s political party – the Jewish labor party (today it would be the Mapai or Avodah) in Hungary within the Zionist movement, was a minority. The majority were either religious Zionists, Mizrachi, or left-wing Zionists, Shomer Hatzair, and general Zionists. And Mapai, the Jewish labor party, was a minority. However, in Palestine it was the majority – the ruling party in the non-independent Jewish community in Palestine. So, it had a special place. And there was constant struggle. And in order to accommodate everyone the compromise was that the head of the underground Zionist movement in Hungary should be a General Zionist, Komoly, who was a Hungarian hero from World War I, and his deputy would be somebody from Mapai. So, chairmanship would be in the hands of the majority and the deputy would be from the minority. That’s the background. And Kasztner was not a Hungarian Jew! He was a Romanian Jew from Cluj, from Transylvania. Before he came to Hungary he was a secretary of the Romanian Jewish representation in the Romanian parliament. So, he was a foreigner. He was a completely unknown personality. However, when the underground was set up and the threat of German occupation came, this underground became important. And Kasztner was a very energetic and ambitious man. So, he became a representative. Also there was an internal decision amongst the Zionist leadership that Komoly and some others would deal with the Hungarians – because he was, after all, very well known amongst the Hungarian elite, a hero from World War I, so he could talk to them – and Kasztner would deal with the Germans. He [Kasztner] spoke Romanian perfectly and German of course, because that was the language of culture. Kasztner became – not by any pre-planning – the representative of the small Zionist minority towards the Germans. So, the negotiations that began were conducted first not by Kasztner, but by somebody much less important, Joel Brand, who was also a member of the Mapai. Then, Kasztner and Brand loved to hate each other. When Brand was sent by the Germans to negotiate with the Allies, Kasztner came in. He wasn’t there from the beginning. That is how he became the negotiator. Basically not representing anybody. This all came later on.

Has the opinion about Kasztner changed? I am not sure. There are still a great number of people who take extreme positions on either side, who will either see him as a traitor and a collaborator and so on, or see him as the ultimate hero who wanted to rescue – which is quite true. I’m not sure that the opinions have changed that much, but they have become more based on factual evidence in a way. And I obviously represent something more in the middle. But I do think that Kasztner was a rescuer. I have no doubt about that. I also think he had not much choice but to turn to the Germans because they were the ones who were deciding the fate of the Jews. And the Jews had no possibility of either rebellion or flight. So, what else should they have done?

On the other hand he was a very unpleasant person. And he was certainly responsible for things that are totally inexcusable, such as, for instance, his attitude to the question of Hannah Szenes, the parachutist, and generally to the parachutists.4 Now, I can understand why he did that because they were threatening the possibility of rescuing large numbers of Jews, in his eyes. Nevertheless, you don’t do things like that.

Secondly, postwar – he was sent to Nuremberg basically by the Jewish Agency and the World Jewish Congress. They tried to hide that. He was just a Jew who had immigrated to Palestine, later Israel. He was sent there because he had had contact with Nazis. What should he do there? My assumption is – I can’t prove it – but my assumption is that they wanted to – through his contacts with the Nazis who were arrested and facing trial in Nuremberg – to get to other people much more important to the Jewish Agency – namely Eichmann, because he had known Eichmann personally very well and some of his Nazi contacts had of course, naturally. I can’t prove it, but that is my assumption. At Nuremberg he did try to rescue some Nazis from trial. Some of Eichmann’s henchmen, for example Kurt Becher. And he lied about it in the trial. He literally lied. There is no question about it. Like with many Jewish heroes in the Holocaust it’s not white and it’s not black. In the case of Kasztner I would say it is white with a lot of grey spots.

You come to recognize a person like that from the testimonies, as we don’t know him. We rely largely on the testimony of his concubine Hansi Brand. I knew Hansi Brand and we interviewed her. And Hansi Brand – I think – was telling the truth.

Dr. Chava Baruch:

We have to make a distinction between the “Kasztner Affair” and what Kasztner and his friends actually did in Hungary. When I ask people today, “Who was Kasztner and what do you know about him?” they are still quoting the decision of the Israeli court: “He sold his soul to the Devil.” People have a lot of information about what happened in the trial of Kasztner in Israel in the 1950s, but there is a huge lack of knowledge about Kasztner and what he and others tried to do in Hungary in 1944. We must first tell the story of Hungary at 1944, so that people will understand the situation then and there, and not examine the story through the prism of what happened in Israel after WWII.

Why did Kasztner become such a controversial figure?

Because when he arrived in Israel in the 1950s many of the Israeli population was made up of survivors. The Holocaust was still a very fresh experience and it was a very emotional experience. There was no real systematic historical information yet at that time; researchers and historians had just started to learn and collect information. There was a gap between real historical research, since there was no historical perspective yet, and raw emotions. Together with the burning emotions of the survivors was the great disdain and mistrust of the native Israelis, who were shaping the new Israeli society, regarding anything from the Diaspora. They looked down on the Jewish survivors who “went like lambs to the slaughter”, and only respected the “heroes” - the survivors who fought as partisans and in uprisings.

The whole trial against Kasztner was a political trial - and we know this today. Shmuel Tamir, the attorney who represented the defendant in the trial, who came from the right side of the political spectrum, didn’t hide his intentions. He found this trial an excellent occasion to attack Ben Gurion because for him, Ben Gurion collaborated with the British Empire, just as the Judenrat collaborated with the Nazis - this was how he presented the issue. And now he had a very good scapegoat. Here is Kasztner who “collaborated” with the Nazis like Ben Gurion did with the British. The question is why was this accepted? The answer is that this was the political and social situation at that time in Israel, it was still early to look at the Holocaust through a different approach.

On the one hand, Ben Gurion tried to shape the new Israeli sabra - the hero - and it was very, very hard to look at this “Diaspora Jew” who tried to achieve results in the same “old” way that Jews behaved in the Diaspora - by talking with and working through the most terrible enemy. This behavior was equated with collaboration. This judgment was a reflection of Israeli society at that time. Today in Israel, we lean more toward negotiation with our enemies, while in 1950s Israel, this was taboo. So Kasztner became so controversial because he tried to negotiate with the Nazis. Who else was he going to negotiate with?

Now, let’s go back to Hungary at that time. What was Kasztner accused of? People asked, “Who gave him the authority to negotiate with the Nazis?” Nobody asked for authority usually, and in that situation especially. Moreover Kasztner was not the leader of the Hungarian Jewry in 1944 in Hungary. In 1944 almost nobody actually knew him – except a very small group of people mostly in Budapest. He was a minor Zionist politician, and was not the head of the Judenrat, or even a major leader. The Jewish leadership was fragmented: each political movement (Orthodox, Zionists, Mizrachi, HaShomer Hatzair, etc.) had its own leader.

Why didn’t he warn the Hungarian Jewry, why didn’t he encourage them to run away or to fight? Kasztner, with his colleagues, described the extermination of the Jews in the Eastern countries in 1943, during a meeting with young Zionists. We have already seen what happened in the ghettos when those youngsters tried to convince the Jews to escape. Most of them refused.

We expect from someone who was a minor political leader to have been much more influential and well known than he was. Moreover, we presume that if he had warned all the Hungarian Jews, all of them would have listened to him, all of them would have escaped, and all of them would have survived! Does this make any sense at all? The question is asked, “Why didn't he save all of them?” Due to the negotiations, it was not only the “Kasztner Train”, with 1,687 Jews that was saved, but 20,000 more Jews in Austria, and yet this question still arises. All of these people, and more, were saved through the negotiations! Instead of asking how many people Kasztner saved, we ask how many he didn't save. If you put it this way, then you can't give even one person “Righteous Among the Nations” status. Instead of honoring someone for saving one Jewish baby, you would instead ask him why he didn't save the whole family.

I had the honor of knowing Hansi Brand. She was the wife of Yoel Brand, and she worked together with Kasztner and together they negotiated with Eichmann. Hansi told me, “You know, Chava, people will never forget that you saved their life - but in a negative way, because they owe you so much - sometimes they attack you.” Hansi also told me that Ben Gurion told her, “If all of you had come back in coffins, they would have named streets in Israel after you.”

We know that Eichmann planned to deport all of Hungarian Jewry. What happened in Hungary that it did not work out as planned? Why did many Jews from Budapest remain safe?

Professor Yehuda Bauer:

The survival of the Jews of Budapest is due to the international situation and to the retreat of the German army, which caused the Hungarian army to do a counter-coup-d’état and get again in control of Hungary. And Horthy stopped the deportations. Horthy in negotiations with the Germans promised the Germans to deport the Jews of Budapest as well. But he didn’t mean that. He was already sending negotiators to Istanbul and to Moscow in order to see what kind of separate peace could be obtained by Hungary. And the new prime minister – after this change – was a general loyal to Horthy – Géza Lakatos – who agreed with Horthy’s policy of trying to reduce the reliance on Germany and possibly negotiate a separate peace. They naively thought the Germans didn’t know that. The Germans knew. But they used also Anti-Hitler, Anti-German intelligence people.

Dr. Chava Baruch:

First of all, we have to understand that Eichmann was a pure ideologist. He really believed in the “Final Solution” and really wanted to execute it. But in Hungary in 1944, he wasn’t as powerful as we believe he was. He was still subordinate to Himmler, who at that time tried to find some way to save Germany without Hitler. Himmler was ready to stop the Final Solution temporarily in order to save the German political entity with himself as leader. Because Eichmann was his subordinate, Himmler knew everything about the negotiations taking place; Eichmann couldn't conduct them without Himmler's approval. So Eichmann wasn’t free to do everything he wanted to do, as he previously had been. As I mentioned before, in July 1944, Horthy stopped the deportations. This was one of the main reasons why the Jews from Budapest stayed in Budapest during the summer and the beginning of autumn 1944. This was the time when the Jews of Budapest were in a so-called ghetto, an open ghetto (without walls around them), they were isolated, they were forced to wear a yellow star, but the ghetto was relatively open. Now on the 15th of October 1944, when Horthy publicly announced on radio that he was finished with the Germans and that Hungary was no longer an ally of Germany, the Germans kidnapped Horthy's son, and they locked away Horthy and his family in a castle. The Germans replaced him with Szálasi, the leader of the Arrow Cross party, and so, from the 15th of October 1944 until the 18th of January 1945, the Arrow Cross was in power. They couldn’t deport the Jews anymore, since by November 1944, the gassing installations at Auschwitz weren't working anymore. This was the period of time when the Arrow Cross simply shot the Jews into the Danube. More than 70,000 Jews were closed into a closed ghetto – they had to leave the Jewish open houses, the “gold star” houses, and they were all concentrated into the ghetto near the synagogue in Dohány Street. Many Jews hid in various places - this was the period during which a lot of the forced laborers were hiding In December 1945, Jewish women and children were sent to build barricades against the Russians - even 60-year old women were building these barricades – but they were dying - so this was a way to kill them when there were no death camps to kill them in anymore. This was the background for Wallenberg's rescue activity as well. He tried to save people by claiming that they were Swedish citizens. The Young Zionists also tried to help save Jews by putting on stolen Arrow Cross uniforms and smuggling Jews out.

These are the main reasons that Eichmann couldn’t do what he wanted to do: the Soviet Army was closing in; there weren't enough Einsatzgruppen - only 200 - to do the job of killing the remaining Jews; and the Hungarians also had their own problems - their Arrow Cross leader left Budapest to return to his home village and the remaining Hungarians all tried to save themselves and to save the Hungarian national treasures because they were afraid the Germans would steal them. It became a struggle for personal survival. It is quite clear that Eichmann wanted to deport all of the Jews of Hungary, but he didn’t have all the means he had before. When the Budapest Ghetto was liberated by the Soviet Army on January 28, 1945, there were still some 70,000 Jews who were still there, still alive. Hungary was liberated by the Russian army on April 4, 1945.

The uniqueness of the Holocaust in Hungary is that more than 560,000 Hungarian Jews were exterminated in a very short time, in the last stage of Second World War.

- 1. Pre-state Israel.

- 2. Generally, agricultural-based training centers for immigration to Israel.

- 3. A Jewish prayer, typically recited in the face of mortal danger or moments before death.

- 4. Ed.: Three paratroopers from Palestine made their way to Budapest in an attempt to save Jews. Hannah Szenes was caught, interrogated and murdered by the Hungarian police. The other two, Yoel Palgi and Peretz Goldstein, went to see Kasztner in his office who convinced them to turn themselves over to the Gestapo. They were tortured by the Germans and sent to Germany, but Palgi jumped off the train and managed to escape and survive the war.