Introduction

Chava Wolf-Wijnitzer with her artwork, 2009

This exclusive interview was published in our newsletter Teaching the Legacy (March, 2009). The original interview was conducted in Hebrew. Chava Wolf-Wijnitzer is a child Holocaust survivor and an artist, born in northern Bukovina (today's Ukraine, near the border of Romania). Her paintings and poems deal with her childhood, most of which was spent in ghettos in Transnistria (near the Dniester river, today's Moldavian SSR). We approached Mrs. Wolf to discuss her childhood, her life, and her creations. We are proud to present selections of her poetry and paintings in this interview. The accompanying lesson plan contains additional poems and more images and analyses of Chava's art.

"The house was very creative. All of this was taken from us. Who knows what we might have become?"

Please tell us a little about your childhood.

I was born in 1932 in the city of Wijnitz, Bukovina, in an area that was once annexed to Austria. We spoke German, but that didn't work in our favor later on. I was born at home with my grandmother and grandfather (on my mother's side) – at that time it was not common to give birth in a hospital. At home there were five of us: our parents, my sister, my brother, and myself. My brother and I are two years apart and my sister is four years younger than me.

My grandfather had a large house with several rooms. He had three daughters and one son, and he dreamt that all of his children would live in that house, but it never became a reality. We lived in Wijnitz until I was five. Grandfather was a tradesman and [he had] two shops in the house. He wanted my father to work with him as well. My father did not succeed in business and consulted a rabbi, who advised him to study to become a shochet [ritual slaughterer]. My father had a beautiful voice. He became a shochet and we moved to a village near Radautz, and my father worked there. We lived on Kargela Street. From the moment I was born, my mother told me tales of the Grimm Brothers and we also listened to music in German. I wrote a poem about this. My father told me stories about rabbis, like the Ba'al Shem Tov [renowned Hassidic rabbi]. So we [had] in our home the religious aspect, but also much European culture. It was in 1939, I think, that I started first grade, until I was expelled from school.

Were there other Jewish children at school?

A few. But I became close with a non-Jewish girl who was a good student. She later told the teacher that I didn't write on Shabbat. There was an inspection and she stood and asked, "Why doesn't Chava Wijnitzer write?" So they said to me, "You don't have to study here." I came home and cried. My mother went to an acquaintance who spoke to the principal about letting me return to school. And I returned, but it did not help. Later they expelled all the Jewish children from school. They forced us out of the villages to the city. In the city we didn't have a house of our own, we had to rent. We also rented our home in Dorshent, but things were good for us there. Father worked. We were not millionaires but we did not lack anything.

In the Other Childhood / Chava Wolf

In the other childhood

German fairy tales

About magical princesses and love stories

And on Saturday nights, after "Havdalah"

A Hassidic tale about the wonders

Of great rabbis

Always surrounded by love.

I was deported to a void!

Our whole lives packed in bags

My mother's hand caresses my head

My father's glance gives comfort.

No more tales of miracles and wonders,

That won't happen here.

The princess now crawls in the snow,

Begging for some bread and water.

Her clothes are torn, her feet frozen;

A princess sick with typhus searches for a bed.

No more light in the castle,

The memory of stories extinguished.

Did you feel different as a Jewish child in a non-Jewish society? Was there antisemitism?

The atmosphere was antisemitic. The Russians entered from the north of Bukovina in the summer or fall, after my grandfather died. [...] My aunt who was a doctor traveled with a pendant of a cross because she heard Romanians talking on the train about what they would do to Jews. They were antisemites. They were members of the Cuza. They had already attacked and murdered Jews. There was also the pogrom [massacre or riot against Jews] in Iasi. We lived in fear. We spent a year living in Radautz and I did not go to school. Until 1941 when the deportations came.

What school did you attend? What did you do during your free time?

I studied in a public school. There were no Jewish schools. In my free time I would collect pieces of fabric from the seamstress to make dolls, or sew something. Though my father was a religious man with a beard, he was also very artistic. [...] He made me a bed for my doll and a closet, [complete] with small hinges. I also embroidered bedding at school. [...] Father once knitted a sweater and I learned to knit from him because my mother knitted so fast I was never able to learn from her. Mother was a housewife who had a feel for aesthetics and beauty. My parents were also talented. At one point Father learned to play the violin. The house was very creative. All of this was taken from us. Who knows what we might have become?

On some level, my own art compensated for what I lost. With colors I express beauty; with poems I express pain.

"I see my fear reflected in their faces. It is very difficult for a child to see these things"

Tell us about the deportation from Transnistria. How did they notify you about the coming deportation?

There was an announcement that we needed to prepare for deportation. So we took long woven rugs and made bags out of them. We packed our things inside, even the rolling pin that my mom used to make cakes. I asked Mother why she would need a rolling pin – she said that when we return we will need even the smallest things from the kitchen. Why? Because my mother remembered that when they were expelled to Vienna during World War I, they were given an apartment, but they eventually returned home. So she thought that this was another wartime expulsion, that when the battlefront comes closer they evacuate the civilian population.

When they evacuated us it was shortly before sunset. Father went out with an oil lamp and asked the gendarme [guard] if he could enter the house and take his Sabbath cap. The gendarme took the oil lamp, slammed it against a rock, and did not let him get it. The humiliation! That was the first trauma.

Then they put us on trains. Father quickly ran to my grandfather's brother, in order to be transported with him. Luckily, we were not sent on the first transports, because those were sent over the Bug River and were murdered en masse. It appeared that God did watch over us after all.

Then we reached Ataki. That was a huge evacuation that assembled masses of people from every area in North Bukovina. I tend to remember the [overall] difficult scenes, not the small details of the events.

I don't know how we managed to cross the river. We paid to cross the river during the day because at night they killed more people. When we got to the other side, two men, who were Jews, offered my father help with the bags, and then stole all of our valuables. If we had kept anything of value, we might have been able to live off them for a few months.

Do you remember who was guarding you – the soldiers and policemen?

I remember the scary faces that guarded us. The majority were Romanians but there were also Germans there. Imagine seeing them as a child. I see my fear reflected in their faces. It is very difficult for a child to see these things.

Tears / Chava Wolf

My eyes are tearing

A drop falls

Holding pain within

Bodies, bodies

Packed on carts

Appear before my eyes

A child looks on and cries.

People, children

Are no more

Images, images

Horror to behold

To shout, to be silent?

Should I tell?

And I cry

Still shedding tears,

Every day

Every hour

Over a vanished childhood.

"What do you do when you can't see or hear in a forest filled with tears?"

Tell us about the evacuation from the ghetto to the forest, where the Nazis forced you to live for months.

They sent us to the forest precisely when I had typhus, so I could not walk. [We were] outside, in the rain and frost. There were thousands of people in the forest. Father created shelter from logs, but it could not protect us from the rain. Because she was a doctor, they gave my aunt permission to return to the ghetto, and she sent us some potatoes. We ate the potatoes raw, by then that wasn't a new experience for us. One day a soldier murdered a young girl in order to show us what they would do to anyone caught trying to bring water from the ghetto without permission.

During our deportation, I was very sick and could not see or hear [anything]. My aunt asked the Romanian soldier if I could sit on one of the wagons that another Jew had brought. He gave permission but the local Jew pushed me and I almost fell. I told the Romanian soldier that I was about to fall off the wagon and he hit the man. When we arrived in the forest, in the evening, I began to crawl in the mud because I could not see. People were stepping on my hands. When we were in the wagon someone gave me a coat, and I continued to hold onto it as long as I could. What do you do when you can't see or hear in a forest filled with tears? When people only want to find a place to rest their heads?

My parents arrived later and asked, "Where is Chava?" Someone said that he heard a young girl crying outside. My aunt and mother went to look for me. They went through the forest screaming, "Chavale! Chavale! Where are you?" Finally someone who knew me picked me up and yelled to my mother, "Rachel, Chavale is with us!" Remembering these stories helped me garner enough strength to raise my own children later in life.

In the forest there was nothing to eat and when a German guard hit me in the head, I developed an infection and became blind.

My aunt said that I would not recover unless I ate. So my grandmother said that we had to sell the coat that was made for me for Rosh Hashanah [the Jewish New Year holiday] in order to buy food. Mother said that she was not ready to sell my coat but that she would rather sell her gold teeth – and that is what she did. She went by the wire fence and sold them to non-Jews.

While in Kopaygorod, they came to deport [more of] us every day. My aunt, bless her soul, really helped us. Each day she would hide us under a blanket, while our parents were in hiding as well. Every day a deportation was carried out to a different destination. One day a soldier found us and my aunt bribed him. My parents would emerge after nightfall.

How much time did you spend in Transnistria? When and how were you liberated?

We remained in Transnistria until 1944 and stayed in Mogilev until 1945, in an apartment by the river. The bridge across the river had been bombed so we were not able to return to Radautz. I went with my girlfriend to sell cigarettes and sandwiches to injured soldiers who had returned from the front. We walked through the trains and crossed underneath them. It was very dangerous, but we didn't think about it at the time. We brought home a few rubles. In 1945 we returned home.

"I didn't want to remain and study [in Romania] because of the antisemitism"

My brother made aliyah [immigrated] to Israel in 1943 with a group of orphans whom the Germans had permitted to leave by boat. [...] When he came to Israel he lived in Kiryat Anavim, near Jerusalem. He married and has three sons. My sister remained with our parents, and finished her studies in textile engineering.

You mentioned the antisemitic atmosphere that existed prior to the German invasion. How were you received after you returned from Transnistria?

The atmosphere remained antisemitic after we returned from Transnistria. After we returned I couldn't even remember the alphabet. I forgot, just like I forgot many small things during the Holocaust. So when we returned I didn't know the alphabet. We did not have a bed to sleep on, and slept on a board. But Mother took me to a private teacher and I studied until 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. I read history books or other books, and managed to pass the exam and get accepted to high school. Back then, a student could begin high school after completing four grades. I was waiting to start school and they told me that my grades were good enough that if I studied a bit more I would be able to begin in the second year of high school. I studied and started school. But I still would not write on Shabbat [– studies also took place on Saturdays]. We had an antisemitic math teacher, and even when I received "10"s on all of my exams, she gave me a "2" because I would not write on the Sabbath. I came home and cried. How is it that even when I received a "10" she failed me? Even the other teachers did not think I deserved that grade. They asked, "Why did Chava receive a '2'?"

When did you decide to move to Israel? Why?

A branch of Bnei Akiva [Zionist youth movement] was opened next to our house. I joined and we used to sing songs of Israel. "The Land of Israel, my beloved land." And I decided that I wanted to go. I didn't want to remain and study [in Romania] because of the antisemitism. I was constantly worried they would kick me out of school again.

Of course my parents were not so happy, but they had been promised that that they would be able to go [to Israel] as well. It was easier to acquire three visas than four. So I went to prepare for a short time in Botoshen. I learned Hebrew there. They sent me to Brashov to train to be a youth counselor, where we received word that we would be leaving. I didn't even have time to go home to say goodbye. Mother could not come because she was very weak, but my father came to the train station to say goodbye. He gave me a watch and some money, and we parted. It was a separation of 18 years. My parents were not permitted to leave Romania.

I continued to hope that my parents would come to Israel. Father would be able to find work and he would also [be able to] pray in a beautiful synagogue, and I could go study at university like any normal girl; but this never materialized. Years passed and my parents were not able to leave Romania. I was forced to compose myself and continue living.

If I had seen reality as it was, would I have come to Israel without my family?"

What happened to your parents and aunt?

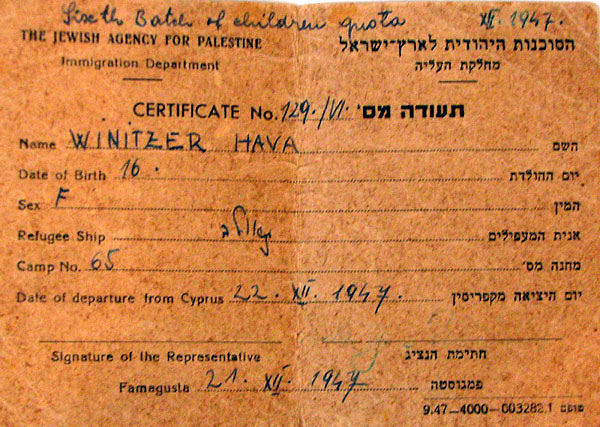

I finally came to Israel in 1947 on a youth aliyah. When we arrived in Israel, they caught us in Haifa and sent us to Cyprus. [In 1947 the British controlled Palestine and limited Jewish immigration.] Once again I saw wire fences and little food. I was in Cyprus from September until December. I was with my girlfriends, most of whom were orphans. They did not have a choice and were forced to move to Israel. I made aliyah because of Zionism. My mother was a Zionist who learned Hebrew as a young adult, and wanted to move to Israel to be a kindergarten teacher.

Do you remember how you were accepted in Israel?

In Israel there were moshav [communal settlement] members who did not accept us into society. [...] New immigrants were not received well. I remember that when we got to Transnistria, the local Jews did not welcome us into their homes. This was really evil. They did not accept us. I, at least, came from a family who cared for my education – most of these girls were orphans. Girls like this must be treated well. What cruelty! They did not want to hear us.

How did you manage with your memories of the Holocaust?

In our house, when we [used to] prepare for the seder [traditional meal on the first night of Passover] [...] that was something. Father wore a white robe, we took down the nice pots from the storeroom. Each person found his/her cup and plate. Grandfather would lean in his chair, and after each part of the haggadah [Passover ritual text] he would hum. Sixty years and I have not forgotten that tune. Then he would continue to read the haggadah.

During the youth aliyah [period], when holidays would approach, I would cry. I asked myself why I had left my family. I was given a rifle to guard the compound. [So] once again I was scared.

The Holocaust would return to me in dreams. I would dream that I cannot breathe, that I'm being strangled. Painting was better therapy for me than psychological treatment.

Describe your life in Israel.

When I left the youth aliyah, someone asked me where I would go. I did not go to a kibbutz [shared communal settlement] because I thought my parents would arrive soon. They finally let me go to a pioneers' house in Haifa. I went to work as a housekeeper. I was glad my parents could not see me like this. Before that, I never even had to wash dishes in my parents' house.

I worked in Haifa and once I had 40 lira I decided to leave. There was a young French woman who suggested that I package oranges at the harbor. I worked there for a bit until I went to work at a store that sold cheese. The owners treated me like a daughter. I continued to hope that my family would return to me. When I left the youth aliyah I waited twice for my parents at the harbor; each time a group arrived from Radautz.

I met my husband Shimi at a friend's wedding. I married him when I was twenty-and-a-half years old. He is also a Holocaust survivor from Transylvania. We moved from Haifa to Jaffa and decided to start a family. A year after our wedding we had a daughter. I think I had a fantasy in my head. If I had seen reality as it was, would I have come to Israel without my family? We lived in Jaffa in one room and then two, and then moved to a housing project.

I began studying. I learned English with a private tutor. I would hear someone tell a child what to do and I would miss the times when my parents told me what to do. I had to make all decisions for myself. We worked hard in order to establish ourselves so that we could move to a larger apartment, so that our children could learn to play piano and go to university. I don't know how I had the strength. It seems that it came from my parents, from the love that I felt from them, and from everything they did for me.

When my parents finally moved to Israel [18 years later] they were older people. I thought they would live forever. I could not ask them questions about our experiences in Transnistria. For years after they died, I kept a picture of them in my closet. It was like I believed that as long as I couldn't see them, they were still alive.

My aunt studied medicine before the war and was supposed to help financially support the family. She never married. She came to Israel and was a regular guest at our house, she was a member of our immediate family. We owned a clothing store and on Fridays, when we did not work, we would take my aunt to the sea to drink coffee and have something to eat.

"The silence took a toll on my health and in my dreams at night"

When did you begin sharing your memories with your family? Did it precede your paintings?

I began writing and painting. I began sharing my story when I had my first exhibition and my daughters heard the feedback. Do you know how important that was as a mother? To feel that my daughters appreciated my work and me. Today they say that their mother is a talented artist. I also needed to feel valued after years of not being appreciated. My daughters ask me if I needed a certificate on the wall. It seems that I do. When my daughter signed the guestbook at the exhibition and she saw the reactions of other critics, she was very proud of me. That was my certificate.

For years, I did not tell my story. If I had told my story I would not have been able to continue living. I wanted to raise my children in a normal environment, even when they were emotional. My husband also did not tell his story. I know what he went through during the Holocaust. He talked about it sometimes, but not to the children. He did not want to sadden or pain them. If we had told the stories, we would not have been able to do what we did. I would not have been able to build a family or send my children to school. My oldest daughter is a clinical dietician, my grandson is writing a Ph.D. dissertation in philosophy in the United States. This is what I attained through silence. But the silence took a toll on my health and in my dreams at night. This silence was not cheap. Sixty years of silence.

"I am in two worlds... If I can paint with those colors, it is a sign that I am still optimistic"

How do you explain your creative process? Where does your creativity originate?

I don't have an idea before I paint. I do not know what I am beginning. When I finish the painting I look at what I have done. Suddenly I see a happy girl with wings. I was a happy girl, who wanted to learn, to dance, and sing.

When I open my eyes I see a beautiful world, trees, flowers. When I close them I am still there, still a child, am still in pain from typhus, still remember how they destroyed our home. I am in two worlds. It is not because I spoke that my pain was gone. It did not disappear. It is difficult to live in two worlds. I am happy and thank God that I can do things, buy a computer, sew dresses for my granddaughters or make the kids costumes for Purim. My children were always greeted with a hot meal when they came home.

You paint with intense colors. What is the meaning of color for you?

I am obsessed with colors. I have to go twice a week into the city, near the open market, to see lots of colors. When I see a nice fabric, I buy it. When I see a nice bag, I buy it because of the colors. I am partial to colors, maybe because of the black that [life] was once. When I tell my story I find myself back there. I am still the same young girl. If I can paint with those colors, it is a sign that I am still optimistic. I write in black on white and I paint with color and hide my pain.

When did you feel you could refer to yourself as an artist?

My friend Sarah Steinberg saved me. She was the one who encouraged me to buy large canvases, take out the paintings and hang them up. It is because of her that I started making large versions of my paintings. I was afraid to make the characters bigger, as if in a larger scale they would be more menacing.

This is the Nazi demon that came into the woods. He had a horse. I made his mouth look like a black hole without "normal" eyes. He used to come and his eyes were light blue, cold as tin. He used to kill people just like that. His boots were leathery, shiny. Notice how many eyes I drew, or no eyes [there are two versions, the painting is a diptych]. And his mouth, when he opened it was scary because he shouted. It was very scary. The sun here is sad. I also drew flowers, I guess I wanted to see flowers. The winter of 1941 was 41 Celsius below zero. People were freezing to death and every day a cart would pass and pick them up. It was terrifying.

Fear / Chava Wolf

I have yet said everything,

It's contained within me, I will not say everything;

Something is clutching my throat –

The fear of opening a window.

The window is open; the black is noticeable.

The moon appears bright and round.

My soul is shrinking

Attacked with fear

I cannot shout

I don't want to cry – I am choking!

After what you have experienced, how would you describe this process of rebuilding your life?

You need something in life to want to return to. I had a bundle of family photos that I later brought with me to Israel. I don't know how I managed to keep it with me during the Holocaust. I was nine years old [then]. At that age you already look at other boys, and there was a kid I had crush on and I very much wanted to come back and see him again. In this context, I remember what Victor Frankl wrote, that you have to have something to hold on to in order to survive. That gives you the strength to carry on.

What message do you have for our younger readers?

I want to impress upon the youth exactly how important the State of Israel is to us. To those of us for whom our lives, our dreams, everything that was beautiful in life were taken from us. I am still an optimist. I still believe in Zionism. When I had an exhibition at "Beit Hatanach" in Tel Aviv, I wrote to many officials and invited them to the exhibition. I want people to hear. I want to tell about what we went through, so that we will not allow what happened to reoccur. I think that we are an optimistic nation. It is a fact that we stayed a nation for thousands of years. How many peoples disappeared within the course of history? We are obligated to remember and to tell our children, [just] as we tell the story of the exodus.

![Chava Wolf [describing the painting depicting the crossing from Ataki to Mogilev]: “They killed people in the river. These are the packed trains. The car is hung in thin air, not going to any destination.” Chava Wolf [describing the painting depicting the crossing from Ataki to Mogilev]: “They killed people in the river. These are the packed trains. The car is hung in thin air, not going to any destination.”](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/wolf3b.jpg)

![Chava Wolf: “Here I express my pain in words [in the accompanying poem 'Tears']. And in the painting I embellish it.” Chava Wolf: “Here I express my pain in words [in the accompanying poem 'Tears']. And in the painting I embellish it.”](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/wolf4b.jpg)