Introduction

Michael Goldman-Gilad was born in 1925 in Katowice, Poland. After the outbreak of the war, he escaped with his parents, brother, and eight-year-old sister to Przemysl. From there, he was deported to Szebnie and later, in November, 1943, to Auschwitz-Birkenau. After a month-and-a-half in the camp, he was transferred to Buna-Monowitz – Auschwitz III – where he worked in the I.G. Farben factories until the evacuation of the camp in January, 1945. He was then forced on a death march, from which he managed to escape and hide with a Polish family. In February, 1945, after liberation, he volunteered to fight in the Soviet army and was wounded in one of the battles. In September, 1945, he reached the Pocking DP camp in Germany, and in May, 1947, boarded the immigrant ship "Hatikvah" to Israel. The ship was seized at sea by the British navy and forced to change course to Cyprus, where Goldman-Gilad spent a year-and-a-half in a detention camp.

After the establishment of the State of Israel, he immigrated to Israel, settling in Tel Aviv, and enlisted in the police. In 1960, following Adolf Eichmann's arrest, he was attached as an Investigation Officer to Bureau 06 – a special unit set up within the police to conduct the investigation. He also served as personal aid to Gideon Hausner, Attorney General, who headed the prosecution. In 1963, he left the police, and was sent twice to Latin America as emissary on behalf of the Jewish Agency. He later returned to Israel and served as head of the Central Administration for Schlichut, managed by the Jewish Agency, until his retirement in 1995. Today, Goldman-Gilad is a member of the Yad Vashem Council, a member of the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous Among the Nations, and a member of the Bialik Institute Directorate. He is married to Eva (nee Goldschmidt), who was born in Jerusalem, and has five children and eight grandchildren. He is currently writing a book of memoirs, due for publication in the near future.

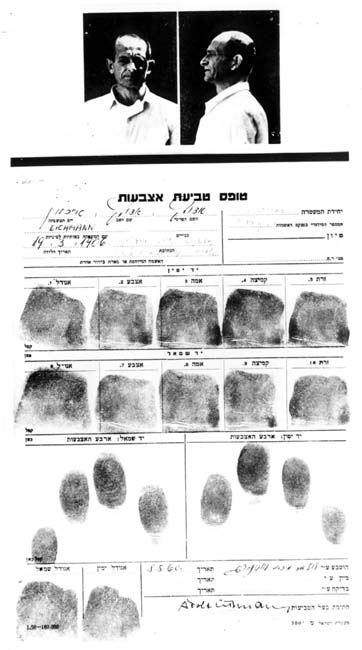

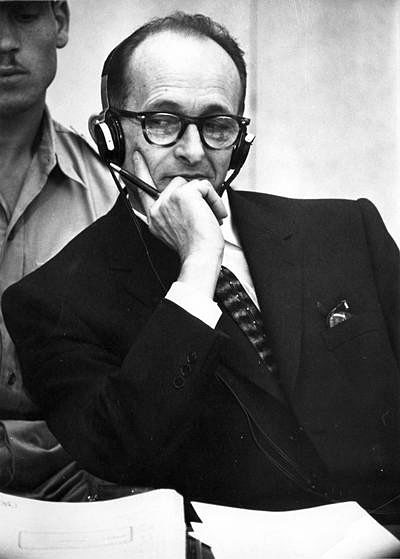

In May, 1960, Adolf Eichmann was captured in Argentina by Israeli Mossad agents and brought to Israel. The Bureau 06 inquiry lasted nine months. This exclusive interview was first published in our newsletter Teaching the Legacy (September, 2007). Goldman-Gilad discusses his time in Bureau 06, the process leading up to the trial, and his own feelings as a Holocaust survivor collecting evidence against a Nazi war criminal.

"We saw the suffering the witnesses were going through" – First Preparations for the Trial

What initial preparations were made for the trial?

The preparations began concurrently with the landing of the airplane that had brought Eichmann to Israel. Bureau 06 was rapidly assembled; we were close to 40 people (including a technical team).

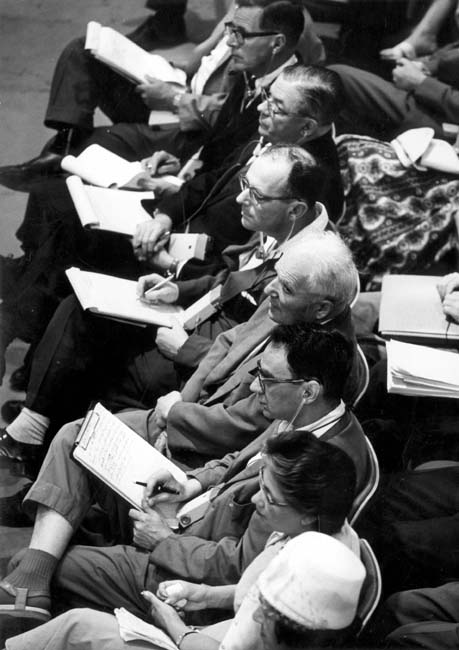

Almost 70% of the Bureau 06 team members were Holocaust survivors. Work within Bureau 06 was divided along geographical lines: we were 12-13 investigation officers, each of us was assigned one area within the territories which had been under Nazi occupation, and we were in charge of collecting the material, locating witnesses and preparing them for their testimony in court. We all had to speak German, and I had spoken fluent German at home. For the entire week we stayed at a motel in Haifa that was rented by the police, due to the secrecy of the investigation. We could not reveal our whereabouts even to our families, because of the total secrecy. The fear was, and not without basis, that there would be an attempt to capture him and rescue him. The secrecy made us uneasy.

We took most of the Holocaust survivor testimony from Yad Vashem. I don't call them Holocaust "rescuees" because no one rescued me [The Hebrew term for "Holocaust survivor" is literally "Holocaust rescuee"], except for one Polish family I hid with after I had escaped from the death march. I am a Holocaust survivor. We are all [in Israel] "Holocaust rescuees" because Rommel came very close to Israel's borders, and if [the Germans] had managed to get through, they would have destroyed the entire yishuv [Jewish population during Mandate Palestine]. So anyone from the yishuv is just as much a "Holocaust rescuee" as I am. I sat entire days extracting this testimony and that, and various segments referring to similar murderous extermination methods that Eichmann had been a part of. We would later meet with the witnesses, in order to ascertain if they were capable of appearing as witnesses, both physically and mentally. Some could not.

As a Holocaust survivor, as someone who had experienced that period, I had a better understanding of the witnesses' manner of speaking, and could gain more trust because they would see me as a fellow survivor. There are some that we did not recommend to testify. We had also been approached by people who had been at other places, some who said they had seen Eichmann and others I could tell "wanted" to see him. We knew that only very few people had actually encountered Eichmann or met him and could therefore testify to that effect and identify him.

We saw the suffering that each and every one of the witnesses was going through, both during the process of collecting the testimony, and later on when they appeared in court. It was a sacrifice for each and every one of them. But it was necessary, because it would be very difficult to conduct the trial solely on the basis of documents; we needed to bring living witnesses to serve as a vital part of what had occurred during the Holocaust.

As experienced investigation officers, we were convinced that our service was for the good of the country, contributing towards cultivating a sense of good citizenship, prevention of crimes, bringing criminals to justice. It was a kind of ideological side to our work – so we referred to it as "service" rather than work.

"When he opened his mouth, I saw the gates of the crematorium"

Each evening we would meet with the deputy head of Bureau 06, Efraim Hofstetter, [the head of Bureau 06 was Rami Selinger, then the Chief of the Investigations Branch of the Israeli Police], to hear the portion of Eichmann's testimony that had been recorded that day, and suggest what to ask and what should be examined more carefully later in the investigation.

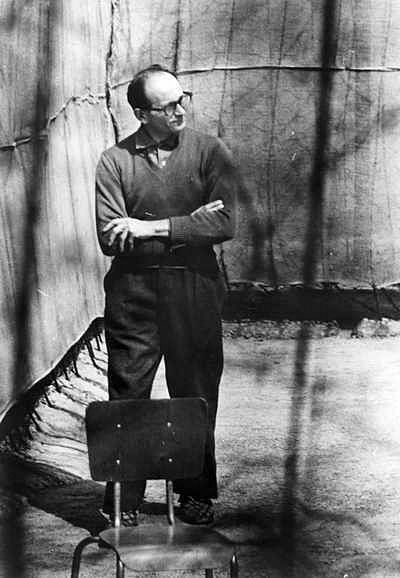

The orders concerning the Eichmann investigation were very clear. First of all, we were to address him courteously. We could not even raise our voice while conversing with him, nor threaten or say he was lying. We could only ask a question so he would further elaborate on a previous answer. There were strict orders to take the explanations from him verbatim.

We had to be especially careful, to prevent claims that he had somehow been pressured. We wanted to prove to the world how exceptional we were, and I think this was overdone. We needlessly treated him like a soft egg.

He knew a great deal about Nazi criminals hiding in South America, with whom he had been in contact during his time there. We had no doubt that he had met Dr. Mengele and other criminals he knew about.

During his interrogation, he would usually lie from A to Z, clear lies and lots of "I don't recall". For example, we wanted details about his visit to the Janovska concentration camp in Lvov, but he couldn't remember. He could remember that he had previously been to the Lvov train station, and precisely what kind of sausages he ate in a restaurant there. In other words, whatever he wanted to remember, he remembered perfectly, and what he didn't want to remember, he didn't. He accepted no responsibility for himself or the documents signed by him. He claimed he had signed them in the name of his superior, Heinrich Mueller, the Gestapo chief.

How was Eichmann's interrogation conducted?

The officer Avner Less would sit with him regularly and collect the testimony. Less was a Berlin native who left Germany in 1933, and was not in Europe during the period of the Holocaust. In the first few days, even before I had joined Bureau 06, he was chosen to be the person who would sit with Eichmann. He spoke fluent German. His German was far better than that of Eichmann, who spoke the simple, vulgar German of the Nazis. Less was a gentleman. For instance, during the first few days we heard Less address Eichmann on the recordings and ask (in German): "Would you like a cigarette, Herr [Mister] Eichmann?" I was furious: "You call him ‘Herr Eichmann'? I was called a dog and you call him ‘Mister'?" Consequently, Selinger issued the instruction to stop the "Herr".

I was in charge of collecting material and proving his guilt for the murder of Jews from Poland, the conquered Soviet territories, Baltic areas, and in extermination camps. This was psychologically the most difficult part for me, maybe physically as well. I met with him [Eichmann] several times to clarify this matter or that, without writing it out, and without it appearing on the protocol.

The first time I sat opposite him at Bureau 06, I looked at him and told myself: "Lord, this was the king of the Jews?" When he opened his mouth, I had the feeling I was seeing the gates of the crematorium. This was my immediate, first feeling.

"We hadn't too much time to think or we might have gone out of our minds"

When you were preparing the material for trial, and heard the testimony, how did you feel?

In one sentence, I felt like I was going through the Holocaust all over again. Both in my time with Bureau 06 and during the four months of the trial itself. In one of the documents I found a letter, dated July, 1942, which the head of the railway system in Germany, Gannzenmuller [State Secretary of the Reich Transportation Ministry], had sent to Himmler's headquarters. He wrote that he was pleased to announce that three trains had been leaving daily from Przemysl to Belzec during the previous week. On July 26, 1942 (I remember this date because it is my birthday), my parents and ten-year-old sister were taken to the Belzec extermination camp on one of these trains.

I read that document and could see the train with my parents. I hadn't managed to say goodbye yet. We didn't know. We didn't believe they were going to die. Only two months later, rumors started arriving that they were being executed shortly after arrival.

After reading this letter, I started searching, to see if there was a reply or mention of it. After going over a few dozen documents, I found the answer from Himmler's Chief of Staff: "I wholeheartedly thank you for your letter informing us of the trains leaving from Przemysl and later from Warsaw to Treblinka with members of the chosen people". I thought of the cynicism in this reference "members of the chosen people". How can I possibly describe how I felt at that moment?

That was only one typical example. When I was dealing with the Einsatzgruppen reports, in which precise numbers were tabulated of those killed – children, women and men – I had to add the figures to get a rough estimate on the numbers of those murdered. I reached close to one and a quarter million people. I was shocked: I had become an accountant [of human life] – children, women and elderly people who had been murdered.

We hadn't too much time to think or we might have gone out of our minds. But we felt a duty to do this. The duty is what kept us sane. We knew that the trial would be public and felt a duty to present this to the world, and perhaps the world would finally wake up. This is nonsense, however – the world never wakes up.

"Only a supernatural power, which I call God, could properly avenge these people for what they had done"

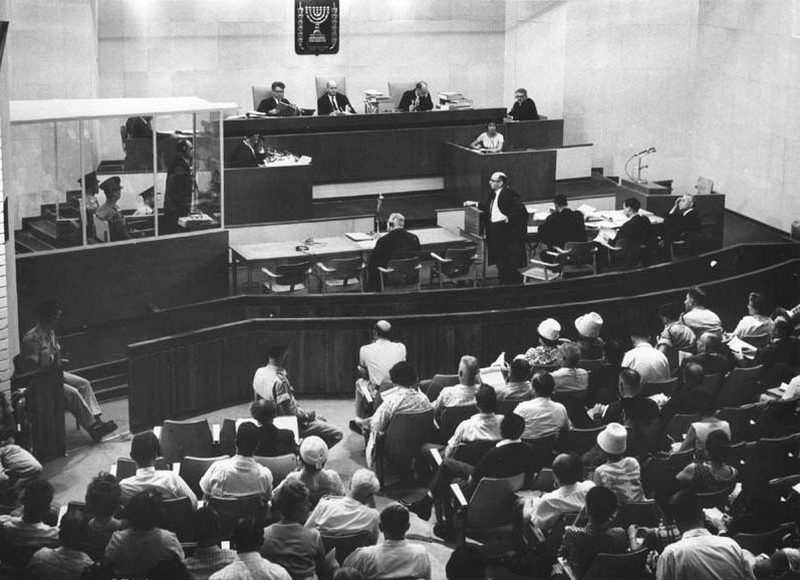

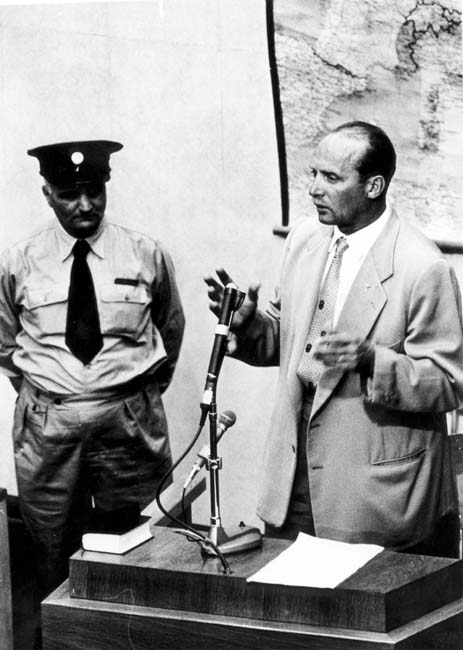

From what you say, the purpose of the trial was not only carrying out justice. You were aware that the trial would be famous, and that stories would be told which hadn't been heard until then.

First of all, this was a just trial, legally. The main legal purpose was administering justice to a mass murderer, proving his guilt with the material we had to collect. That was the dry, legal aspect of it.

The wider purpose, as far as I knew then, was to present the totality of the murder of Jews in Europe to the world, so that it would never be forgotten. This was all of seventeen years after World War II, and we felt that the world was beginning to slowly forget. This wasn't only the Eichmann trial, it was the Holocaust trial.

We weren't sure we'd get another opportunity to bring the full extent of the Holocaust to the world's consciousness, and especially the Jewish people and our own youth, which didn't know much. That's indeed what happened. It had the educational importance of the first degree, showing what happened and what had to be done so this wouldn't happen again.

I've been asked if I saw it as revenge – this was no revenge. How do I nevertheless justify the mental anguish I had to endure during that period? In that in some way, we showed our tortured people that we must do everything possible to ensure that we never reach this situation again. That's my satisfaction. If I feel we've fulfilled that aspiration – that's another matter. It's a personal feeling. I very much doubt that we've learned our lesson.

Do you feel that by the very conduct of this trial, justice was served?

Justice was served to one murderer, a formal justice. He can't be hanged more than once; but that is not the absolute justice. Justice was not served in comparison to what was done to us. This is why I say that I don't know what revenge is, but only a supernatural power could properly avenge these people for what they had done, [a power] which I call God.

I'm not saying that everyone was guilty. I can't say that the German people murdered the Jewish people, one can't generalize in such a manner, because amongst the Germans were also those who saved Jews, and I deal with these cases as a member of the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem. If we generalize and claim that all Germans are guilty, we perpetuate antisemitism to a certain extent, which sees all Jews as thieves and cheats, capitalists, communists and what not...

I think one of the important achievements of the trial was that as a result of the witnesses' appearances, Holocaust survivors finally began to speak out, to tell their stories thinking that they will be believed. I was part of this. It gave me more confidence as well. I am convinced that if it weren't for the trial, many Holocaust survivors would have passed away without ever having told their stories. Maybe they would have left their personal memoirs at home, in a language that the children could not understand. This would have undoubtedly been a tremendous loss to Holocaust history. I am certain there are still things they haven't told. Not that, God forbid, they should have felt ashamed; it was only out of a doubt on their part that things happened to them which could not be believed. It's human.

Did you feel you wanted to testify during the course of the trial?

No. I wasn't the subject, and I didn't offer myself. There was no need to bring me as a witness – I belonged to the investigation and prosecution team. I could have testified, for example, about Auschwitz, but we had many other witnesses who could as well.

Take, for example, K. Tzetnik, who testified – or started to testify – about Auschwitz. In effect, the aim of bringing him as a trial witness was not only his testimony about Auschwitz. I know this personally because I collected the testimony from him before he appeared in court. He did not want to appear. He needed to be goaded, convinced, to appear as a witness, about Auschwitz as well. When he finally started talking, and I started collecting the testimony, it turned out that in one instance he had met Eichmann. This is what determined Hausner's decision to summon him as a witness, but he did not manage to tell the story in court and collapsed at the witness stand.

"A story that other than once before, I've never told anyone"

Although you yourself did not testify at the trial, your personal testimony was eventually heard in court.

The story of the eighty lashes was made public at the Eichmann trial without my consent, in a testimony delivered by Dr. Buzminsky, an eyewitness to the eighty lashes I received. This is a story that other than once before, I've never told anyone.

What was it that you were being punished for?

While at a labor camp in the Przemysl ghetto – I was young, sixteen-and-a-half, closer to seventeen years old – and belonged to a group of boys called the "Transport Commandos". We weren't skilled laborers, so we were made porters. We had a horse and carriage, and under Gestapo supervision, we had to enter abandoned homes, empty the contents, and transfer it all to warehouses in the camp, in an orderly fashion: closets here, books there, shoes here. The collected possessions from the abandoned homes were processed at workshops by skilled workers: cobblers, tailors, and other artisans. They would process, launder, and repair the collected property, and this would be sent to Germany.

In the summer of 1943, shortly before they liquidated the ghetto, the SS discovered that the person operating the Przemysl railway station was a converted Jew, and he was executed together with his family, even though his wife wasn't Jewish. We had to go to his home, which was outside the ghetto, with our carriage, empty the house, and transfer the contents back to the camp. When we entered the house, I saw a very large library in the living room, and when we started taking the books out, I saw he had many books about trains. He was director of the train station and also a rail engineer.

We already knew about the trains. We knew what was going on, where Jews were being taken on the trains. I decided that when we brought these books into the camp, I would hide them so they wouldn't reach German hands. This was sabotage of the first order, punishable by death.

When we reached the camp, I placed these books separately. With the help of some friends who were with me, we hid them in various workshops, so they wouldn't reach the hall that was serving as a library, where they would arrange the books by subject. The Jewish prayer books would be gathered separately and sent to Berlin to the Alfred Rosenberg's "Institute for the Study of the Jewish Problem".

Three days later, I suddenly hear someone calling me. The Jewish head of the camp is calling me to come out; I didn't know what for. I see Josef Schwammberger, who was the commander of several camps – Przemysl among them - on behalf of the SS, standing next to him, with a dog restrained by a leash. He had a heavy leather leash, with an iron buckle. He used to yell at the dog "man, get the dog!" (in German), and the dog would attack. That was his expression. This is why, when we were interrogating Eichmann, I was so angry at Less for referring to Eichmann as "sir' – I was called "dog" and he'd be "sir"?

We all knew that if someone was summoned to Schwammberger, he was finished, because Schwammberger used to draw his gun and shoot for no reason. And so if there was a specific reason, all the more so.

I had no idea why I was being summoned to Schwammberger. I approached him. He removed the leash from the dog and looked at me. He had the same murderous look even [much later] when he was on trial as an octogenarian. He asked me: "To whom did you sell the books?" (in German). In the first moment I was confused, but I came to my senses and realized what this was about. I instinctively found an answer, I had to find some answer. I said that when we reached the courtyard with our carriage, it was time for a lunch break, we went to eat the soup we were given, and when we returned to the carriage, the books were no longer there – meaning that people had taken the books to read them.

Schwammberger struck me around the neck with the leash and said, "bring the bench!" I understood he did not believe my story.

The bench was a special bench where they would lay down whomever he [Schwammberger] decided would receive 25 lashes. After 25 lashes with the buckle at the end of the leash, he would then transfer the person to Ghetto B. (There were two ghettos: Ghetto A, which was the workers' ghetto overseen by the SS, and Ghetto B, of the "non-workers", overseen by the Gestapo, and Polish police at the entrance. They would occasionally transfer people from Ghetto A to Ghetto B, where the women and children were, and from where transports were sometimes sent to the death camps. Where we were, in Ghetto A, there were no longer any children.) After 50 lashes he would take out his pistol and fire; we knew that.

When I was laid down on the bench, I started counting. I thought I could last for as many lashes he would give, if it were 25 or maybe more. He started beating me, and I through the beatings I managed to count 13, 14, 15, and then fainted. Later, when I awoke, I again felt I was being beaten, and fainted several times.

Suddenly I couldn't feel anything. I didn't know there were eighty lashes. During the lashing, they took people out to the courtyard to be witnesses, and they were the ones who counted. My friends are the ones who told me later. They said they wanted to know if I am to be transferred to Ghetto B or shot. They are the ones who counted eighty lashes. Dr. Buzminsky stood in the courtyard, saw and counted [...]

Everything fell silent. I awoke and heard Schwammberger's voice, "aufstehen!" (get up!) I want all the books back here in three minutes!" (in German).

I still don't know where I got the energy from to get up and run with my friends. We ran together and took out the books. We piled the books by him, far more than there originally were at the rail engineer's [library]. I waited to see what would happen. I'm standing and the blood is dripping from my back. He picks up a book – it was a Jewish prayer book – and said, "was this also here?" (in German). He gave me one more beating around my neck and said, "get out of here". I walked to some corridor, and lay there for several days.

Two months later, a selection took place. We had to stand in a line at a courtyard, where Schwammberger sat. Each person had to approach him, place his labor papers and he would look [at them], ask a few question – or not – and then stamp: "Gültig" ("valid") or "Ungültig" ("invalid"). I knew that those that were stamped Ungültig were immediately taken towards the gate, and I was afraid he would recognize me.

I approach him, give him my papers and he looks. "Ah, it's you who received twenty-five?" We had to call him "Herr Leiter" (leader sir), and I tell him "Herr Leiter, there were eighty". My nerve, I don't know where that came from. He apparently liked my answer, gave me a smile and stamped me "Gültig".

In 1991, when Schwammberger was captured in Argentina, the Germans looked for witnesses that could testify against him. I was summoned to the police station in Jaffa, when I gave my testimony, and among other things I told of this case. When I testified against him in court in Stuttgart, I spoke for many hours. I didn't testify just about myself, I was also there when he shot one of the boys in the courtyard, in my presence. It was right in front of my eyes.

When I was testifying about this murder, the judge asked me, "and what about the eighty lashes?" I started to tell the whole story. The judge looked at Schwammberger and saw he was smiling. Schwammberger remembered that case, in court. The judge stopped the proceedings and said, "and he's still smiling?" Schwammberger went to prison - he received life imprisonment. The court refused to pardon him and he died in prison in 2004, aged over 90.

A month after returning from that trial, I had my second heart attack. There's no doubt it affected [me].

"I don't know what hurt more – the eighty lashes, or the eighty-first I had received"

It appears that Gideon Hausner knew the story when examining the witness, Dr. Buzminsky, and asked if he saw the boy in court.

On the day Dr. Buzminsy delivered his testimony, he arrived that morning in Jerusalem. I had not met him since [the time at] Przemysl Ghetto; I didn't know he was alive. He arrived at the courthouse before the beginning of that day's sessions. He saw me, an officer in police uniform, approached me and asked where Gideon Hausner's office is. Naturally, I asked him why he was looking for Hausner, and he answered that he had been summoned as a witness for the trial that day.

I usually knew which witnesses were to be summoned on any given day. For that morning, however, I didn't know because I had arrived the day before from Germany, after a trip on behalf of the court. I asked what he had been called to testify about, and he said that it was about the ghetto at Przemysl.

Our conversation was conducted in Hebrew. I asked, "Przemysl Ghetto? What were you called at Przemysl Ghetto?" And he answered, "my name is Dr. Buzminsky". I asked what he was called in the ghetto, because I could not recall anyone in the ghetto named Dr. Buzminsky. He asked where I was from, and I told him that I was from Przemysl as well. He asked for my name, and when he heard it was Goldman, said "I knew a boy named Goldman who got eighty lashes from Schwammberger, but we heard later that he died". I answered, "he's not dead; he's standing here in front of you". I later identified him as Dr. Diamant, who was a dentist. He entered Hausner's office and must have told him about our conversation. When Dr. Buzminsky gave his testimony on the witness stand, Hausner surprised me, because I didn't have a clue that the witness had told him about our conversation. He asked him if he sees the boy in the courtroom. He pointed at me and said, "it's the police officer sitting next to you". I sat [there] frozen, and at that moment, the cameraman filmed me and that's the picture that was publicized.

During the break after Dr. Buzminsky testimony, Hausner approached me and asked how it was possible that we were sitting together every evening, talking and reading hours and hours of testimony of witnesses that we were going to summon, and that I hadn't told anything about myself. He wondered how it was possible that he should hear this from someone who had entered his office by chance. I explained that I had once told my story to a person who was sitting with his wife, and that after I had finished, he told her in Hebrew, "they've gone through so much, they must be mixing reality and fantasy". I understood Hebrew, because I learned it as a boy. And then I told myself, "that's it. We're through. So we won't tell any fantasies". In my opinion, this happened to most of the Holocaust survivors; that people wouldn't believe them.

My conversation with Hausner was in the presence of Haim Guri and Antek Zukerman, who had also testified that day. So I started to say "and this was, for me.." and one of them completed, "..the eighty-first blow". That was exactly what I had meant to say, only I added that I didn't know what hurt more – the eighty blows or the eighty-first I received when they wouldn't believe my story. Since then I shut myself off [from the world], and I haven't even told my wife or children about this case.

"This time it wasn't my Auschwitz, it was his Auschwitz"

Was it clear in advance to the prosecution that the trial would end with a death sentence?

No. But we were convinced we would prove his guilt. [The sentence] was up to the judges, and we weren't one hundred percent certain that they would impose the death sentence and that the sentence would be upheld after appeal to the High Court. Also, there were rumors circulating while the appeal was being presented that some people would request that he be pardoned, including some living in Israel. Martin Buber, for instance, objected to capital punishment on principal. Gershom Shalom objected to his execution, claiming that by doing so it would somehow be seen as a final "settling of the score" with Nazi Germany, as well as others.

When the verdict was upheld at the High Court, Servatius, Eichmann's defense lawyer, requested a pardon from then-President, Yitzhak Ben-Tzvi. The request was brought to a government hearing, in which several doubts were raised. There was no unanimity of opinion. They submitted the request to President Ben-Tzvi, and waited to hear his assessment. The President decided not to pardon Eichmann, and in his response to the request, cited the verse, ""As your sword has made women childless, so shall your mother be childless among women." (1st Samuel, 15/33).

That day, it was decided that Eichmann would be executed at midnight, because they feared a flurry of pardon requests from around the world. That afternoon, I was summoned to Aharon Sela's apartment at the police station in Ramat Gan. He told me that it was decided that I would be one of the two witnesses present at Eichmann's execution. The other was officer Franco, commander of the prison guard unit that was assigned to guard Eichmann while he was in custody. He asked me to return to the police station at 21:00 at night, and not to speak with anyone until then.

What feelings did you have from that moment on until 21:00 at night?

I can't recall exactly how I felt, but there was, no doubt, a feeling of satisfaction that the sentence was finally due to be carried out. It was satisfaction but not surprise. I knew that ultimately we couldn't do otherwise, that would have been untenable to me.

That evening, I went to the prison in Ramle, met the prison warden and waited until midnight. We were joined by the head of Israel's Prison Service and Reverend Hall, an Anglican minister, who tried to extract a confession from him, but Eichmann refused to confess.

We were later joined by four journalists [...] All together we were ten. [...] Two minutes before midnight, Eichmann was taken from his cell and put into the gallows cell, where the hanging post stood. On the right was a screen, and we knew that behind this screen stood two Prison Service personnel, and they had two buttons; upon giving the order, they would press both, and only one was actually functional. Two additional Prison Service personnel tied his legs and arms. They wanted to place an eye covering, but he refused. We stood opposite him. I stood three feet from him.

In my opinion, he was partly dazed. He had previously drunk half a bottle of wine, asked for a pencil and paper, and written letters to his family. When he stood under the gallows, he tried to hold steady. Anyone who knew him could recognize when he was angry. For example, during the investigation, when he was having difficulty giving a potentially incriminating answer, his left little finger would quiver. That moment, when he stood under the hanging post, I looked at his little finger and saw it shake.

He was without glasses, and while they were binding his arms and legs, he saw that the reporters standing had taken out their notepads and begun to write; so he started speaking, "Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are three countries I owe so much to, while we still had time to meet as mortals. I performed my duty. I fulfilled orders."

I didn't feel anything. No feelings of revenge, because there was no revenge. No human can avenge what they did. Only God can. One person had been hanged - Compared to all the others? Compared to my family? Compared to my ten-year-old sister who was murdered in Belzec together with my parents? I didn't feel a thing. I felt like I was seeing something that I wasn't a part of.

On the order "activate", the Prison Service personnel pressed the buttons. We then signed the protocol confirming that Eichmann had been executed by hanging in our presence. I signed first, then Franco.

The reporters left. Franco, myself, the minister and several other prison guards accompanying us went downstairs and began walking towards the oven that had been brought especially and that was placed in the prison courtyard. It was a dark, overcast night. We walked along the lights by the prison fence. I knew we were headed towards the oven, where they would be bringing Eichmann's body for burning. I looked at the lights and thought to myself: like in Auschwitz; but this time it wasn't my Auschwitz, it was his Auschwitz. Later on, his ashes were placed in a two-liter milk jar. I don't know if it was half or three-quarters filled. I was astounded to see how little ash remains from one body [..]

Standing there, I remembered that about a week after I had arrived at Birkenau, in November, 1943, I was taken out of the bloc with a group of some ten prisoners, and we were led towards the crematoria. We already knew what was happening there, and thought we were being led to our deaths. The ground was icy and we were walking with our wooden "Dutch" shoes. A Polish capo stood there, with some SS men. We were brought to a mountain of ash. We were told to get wheelbarrows, fill them with ash, and scatter it on the routes the SS guards would take during their patrols, so they wouldn't slip. It was a full day's job. Later, we were returned to the camp.

The next day they took another group, and rumor was they never returned. Immediately after they had removed Eichmann's body and I saw what was left of it, I understood how many hundreds of thousands must have been in that ash pile; it's an association I won't forget for the rest of my life.

Along with the jar, I went with the head of Prison Services to the port at Jaffa. We boarded a police boat, and set sail. When we had reached a point six miles outside Israel's borders, he opened the jar, and together we poured the ashes into the sea. At that moment, I instinctively said "thus let all your enemies perish, Israel". Someone next to me answered "amen".

We headed back, and the sun had come up. The fishermen were returning from their nighttime fishing, and we saw Tel Aviv awaken to a new day. After disembarking, there was a small group, probably port workers, who applauded and hugged us. When I saw this, I suddenly felt we were alive: the sun was shining, we are in Israel, and in Israel there is life. The nightmare was over. A new chapter had begun.