Can you tell us about life before the war?

I belonged to the Zionist stream of youth organizations and was a member of "Akiba" and "The Zionist Youth." My membership started two years before the war.

Can you describe the first days of the war?

If I recall correctly, I was in town on my way to school and suddenly we heard many planes in the air. The public tram stopped in its tracks and some people said that they were Polish planes circling whilst others understood the truth. When the bombs fell, all doubt was removed and World War II began with a German air attack. The difficulty of acquiring food started right from the first days with a worsening of the situation from day to day. Public morale ebbed and panic set in. The air attacks intensified and in various places it was hard to identify a street that had just been reduced to rubble. I remember that our house was bombed one day after Yom Kippur. Two bombs smashed through the building and many of the people were injured and killed. Of my family alone, seven close members were killed, including my grandparents and my brother Israel, who was younger than me by a year and a half. My mother was injured and I myself was badly wounded. When I regained consciousness, I found myself under wreckage of the house. Only after I managed to extricate myself did I see that our house was totally destroyed and no sign of life was to be seen. I got to the shelter of the neighboring house and found both my parents and my sisters. I learned that the rest of the family had been killed. Later on, my father’s shop was taken from him and we were forced to wear a badge of shame for the Jews. Thereafter the ghetto was established.

What do you remember of life in the ghetto?

Shortly after the establishment of the ghetto, my parents sent me to relatives in the village of Klwów near Radom. I remained there for three months, until mid-1942. Klwów had a ghetto without a wall and it was here that I saw for the first time a German killing a Jew and how his blood flowed. He had been caught outside of the ghetto and even though there was no wall, it was prohibited to exit the ghetto limits. The head of the Judenrat arrived and begged for the Jew's life, but to no avail. They shot and killed him, departing on their horses. Simple. That was the first time I witnessed killing.

During the big transports I wasn’t in the ghetto, but after I heard what was happening, I got up one morning and returned home [to Warsaw]. I remained in the ghetto like everyone else. When I first saw the ghetto after my absence from it, I was shocked although I had heard while outside what was going on inside. I continued to meet with members of my youth movement and during this period certain members were chosen to be active in the initial organization of the Jewish fighting force.

Can you describe the atmosphere in the ghetto on the eve of the uprising?

We knew that something was about to happen but we were unable to grasp that total annihilation of a whole ghetto could actually occur in the heart of Europe in the mid 20th century. It was impossible to accept and internalize this fact, especially for the older generation. I was a young fellow of 18 or 19. - The older generation, like my parents, still remembered the Germans from the First War and the fact that they had related to the Jews reasonably. So this [mass murder of the Jews] was an impossibility. How did we persuade them that the situation was different? One of the Bund members, Zalman- Zygmunt Fryderyich, was sent to follow a train to Treblinka and he returned with these indisputable facts. Although Treblinka had been thoroughly hidden in a forested area, and nobody could know what was going on in the camp, two things could not be disguised. One was the billowing smoke from burning bodies and the other factor was the very distinct odor of burning these same bodies.

In addition, a few people individually managed to escape from Treblinka and one of them was a cousin of mine. He hid at the bottom of a massive pile of clothes that had been loaded on a train in Treblinka and he found himself outside of the camp. He returned to the ghetto and related everything but my parents refused to believe him.

Could you relate to us what happened to you during the uprising and afterwards?

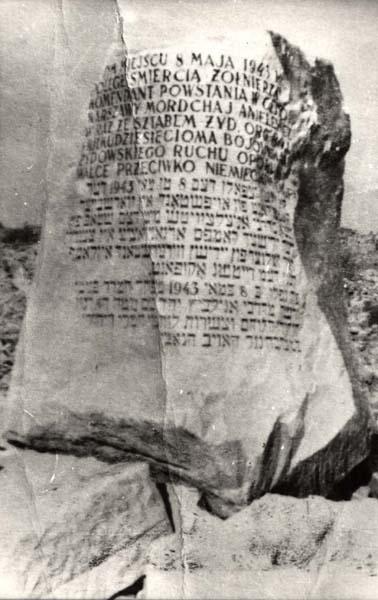

The uprising began on the 19th of April which was the eve of the Passover festival. The Germans liked to needle the Jews on festivals so they planned the beginning of the liquidation on the eve of this holiday. Right at the beginning, when I saw the mass of German forces enter the ghetto, my first reaction – and I guess I wasn’t alone in this – was one of hopelessness. What chance did we have with our miserable supply of firearms to hold off this show of German force with machine-guns, personnel carriers and even tanks? With masses of infantrymen, hundreds if not thousands, of soldiers on motorcycles and ambulances and more… An absolute sense of powerlessness was pervasive. I was on guard with Zippora Lerer and I shared these thoughts with her then and there, but a second thought intruded almost immediately: it had been for this moment that we had anxiously waited. And after we got word of positive developments in the area of the Central Ghetto and similar successes on the next day also in our area, a tremendous uplifting of the spirit set in. In other words, our emotional reactions were like extreme swings of the pendulum, from hopelessness to great excitement as if we’d achieved victory over the Germans. In actual fact, it was clear to us even after the initial German shock that our fate was predetermined and that it was only a question of time. Nonetheless, the feeling that the all-powerful German who normally wielded absolute power over us had been beaten back, even if temporarily, gave us much to proceed on. These changing circumstances and alternating emotions were the rule for the first few days. Our group was on 6 Walowa Street (the Brushmakers' Area), and we had a vantage point at the highest spot from which we could observe the gate opening on to our area. Next to the gate, near the entrance, we had planted a large amount of explosives ready for detonation whenever the Germans planned their entry and our job was to push the button at the right moment. At our position, we had the electrical connection for the detonation and a button for calling forces at any moment. In actual fact, we had all been in readiness since the time of the German entry into the Central Ghetto on the 19th of April and we knew that it was only a matter of time before they would enter our area as well to begin the liquidation. But not everyone was in their positions and hence the importance of the emergency button. On April 20th in the early hours of the morning – and my luck was that I was on guard duty at that moment – I suddenly spotted a group of several hundred SS men marching and approaching the gate… the first ones were actually past the gate when I pressed the emergency button and in my other hand I held the detonating connection. My commander, Hanoch Gutman, ran into the position and since he saw from our window exactly what I saw, there was no need for my reporting to him. He grabbed the connection from me, waited another few moments as I had in order to create the greatest havoc in the middle of their column with maximum casualties, and then detonated the explosives. I was shocked into inaction after the massive explosion with the sight of smashed limbs and German bodies flying in the air. This German people that had conquered Europe and knocked at the gates of Moscow – this was not a spectacle that we were used to and certainly not in a ghetto, Jews killing Germans. It was something extraordinary…I was actually paralyzed for some time by the sight of Germans running away from the havoc. Up to this point, for years we had been used to the sight of Jews running for their lives, or of non-Jews, but not of Germans. This was the first time since the war had broken out that the Germans were running away.

Can you describe what happened afterwards?

At a certain point, the Germans set the whole ghetto alight with flames everywhere. We knew that this spelled the end for us, that everything that we had been told was the truth and that remaining in the ghetto simply meant being burned alive. But despite what the Germans were doing, most of our fighting force was still alive. So the question of what to do in this new situation now arose. And suddenly, it appeared that nobody had thought of this eventuality, although some claimed that there had been some thinking on this scenario but no plan of action had been devised.

For me, thinking and planning is very important, but there has to be some kind of action to put plans into effect, and here no concrete action was immediately evident.

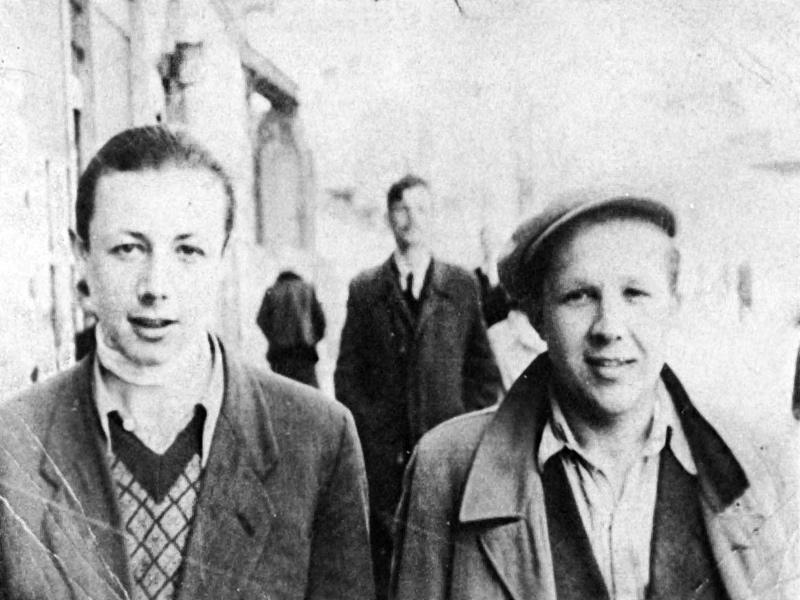

On one specific day during the rebellion, two friends came to me from the fighting force. One of them was Marek Edelman, a prominent member of the Bund and my personal commander. They asked me if I was prepared to try and get out of the ghetto [in order to organize a rescue from the Aryan side]. I answered "yes" – I had nothing to lose. I already knew what the alternative of staying meant. They sent two of us on this mission, myself and Zygmunt Fryderych.

But how to get out safely? We tried different ways but the ghetto, surrounded by a high wall, was very well-guarded from the outside by units of Germans, Ukrainians and Polish Police. They were set on preventing any Jews from fleeing their fate.

We found a tunnel that led from one side of the street [inside the ghetto] to the other [on the Aryan side] but we had no idea who had dug it. Later we discovered that the Betar members had been responsible. We arrived on the Aryan side on May 1st at night and decided to stay until daylight in order to familiarize ourselves with the surroundings. Suddenly someone came out of a building and when he saw us, he immediately tried to retrace his steps but I prevented him from closing the door on us because it was important for us to speak to someone and gain information. He bought our fabricated story that we were two Poles who had been trapped in the ghetto and only now had we managed to escape. He congratulated us and furnished us with very important information. Firstly, he warned us not to exit via the gate because it was guarded by Germans. Then he told us about bodies in the yard and on the roof, which we saw. We understood that there had been some kind of incident. Later we understood the bodies were those of Betar members who had been connected to the right-wing Polish underground that had in fact betrayed them. That is, when the Betarists left the ghetto the Germans were already waiting for them, and not one was left alive.

Our problem was what to do with our members who were still in the ghetto? How were we to get them out? We grasped early on that we needed a means of access where we could easily get into and out of the ghetto. We understood that our only hope was the sewers, that this was the only chance we had to get back into the ghetto and carry out a rescue mission. We got to someone called the “King of the Blackmailers.” He lived on the ground floor which enabled one to climb out of his window and enter directly into a sewer without the guards seeing us at the gate to the house, thus eliminating the danger of the guard at the entrance to the building handing us over to the Germans. This "King," just as I was about to enter the sewer, indicated that he knew I was Jewish. I managed to persuade him that my mission was to save a group of Poles in the ghetto and that on my return we would discuss it in full. He let me depart into the sewers. Without guides down there one would get lost in the labyrinthian network of pipes. We managed to enlist the help of two Polish sewer workers to whom we told the same story as we told the "King." “You will be thanked in the annals of the Polish Resistance.” They agreed to guide us but after a short distance they wanted to return. At this point, I directed my pistol at them and left them little choice. After some time, they told us we were now under the ghetto area. I climbed up and out of the sewers leaving my comrade to guard them. After having been out of the ghetto for only a few days, suddenly seeing it again was a big shock. I couldn't recognize anything. Everything was destroyed!

How much time elapsed from leaving the ghetto until you returned?

I left on May 1st and returned in the night between the 8th and the 9th. It took just over a week and felt like eternity. I should mention that Antek Zukerman was also on the Aryan side of Warsaw and I had to report to him as well. It was immediately clear that he had no way of helping us out. He was unable to think of any solution at all. He was thinking of returning to the ghetto because of his sense of helplessness outside. Of course, this also would not have helped any. We could not return via the tunnel we had used to get out because the exit/entrance was now guarded by Germans. We were also keenly aware that every passing moment was making any chance of rescue more remote.

Whose idea was it to use the sewers?

I don’t know who had the idea first but many people used them.

Where did you come out of the sewer and into the ghetto?

I came out where there had been one of the entrance and exit gates of the ghetto since its establishment….In any event, I found myself again inside the ghetto. I knew exactly where I was, I was able to identify the spot, and I started running around, trying to find where I knew [the fighters would be]. When I had left the ghetto it never even occurred to me that the situation could change, that people would move to other places, to other bunkers, other cellars...everyone was looking for someplace to hide. In short, I look around and I get to one place, to another place, to a third place, and I'm running like a crazy person. There's no answer anywhere. No one responds. And then, suddenly, a voice rises from the ruins – it was the voice of a woman, who is lying somewhere amidst the debris – because there is not even one house that's still standing in its entirety, nothing! I begin speaking with her and I ask her, "Maybe you heard? Maybe you saw? Maybe you know something…?" And she answers me, and I try to find her but I can't. I spent some long moments looking for her that seemed to me like forever. In the end I gave up and I continued walking. After all this I had a moment of weakness or… I don't know how to explain my [mental, emotional] state. I sat down among the ruins, somewhere, I don't know for how long. Apparently, for a while. I didn't know what to do and I thought that I must be the last Jew alive in the Warsaw ghetto or maybe even in all of Warsaw. I thought I would just wait until morning when the Germans would come, and then I would have two possibilities: either I would succeed in killing one or two Germans, or they would kill me and that's how the story would end. I sat there, almost calm even, and I didn't know what to do – to go or not to go – I had no place to go. No one had answered me, there was no trace of anyone left. Suddenly I remembered that the two sewer workers and my friend were still waiting for me in the sewer, and I decided to go back there. They had waited where they were, and we began to walk back through the sewers, slowly, without having achieved anything. Nothing.

At this point something impossible happened, so impossible that it's difficult to believe that it actually happened, but it's a fact. I started to hear murmuring in the sewer, but I wasn't sure and I didn't know who it was – maybe it was the Germans. The whole thing occurred in a matter of seconds, and suddenly inside the sewer we met up with ten Jews I knew, among them – the first one I saw – was Pnina Greenspan. You can imagine such a meeting, suddenly, inside the sewer – joy and elation! In the meantime I had almost lost the sewer workers because they didn't want to wait anymore. They had already understood what was going on, so we had to do things very, very quickly. One of the people in the group was Shlomo Shuster, who was younger than I was by one year. I knew him well and I trusted him. The first thing I asked him was whether there were still people from the ZOB left alive and whether they were still inside the ghetto. He answered in the affirmative. I asked him to take one additional man, to return to the ghetto and to bring everyone to the sewer. I gave an order to wait under a specific manhole cover where there was an exit from the sewer, from which I would leave. On the way I had used chalk to mark the path we had taken. (I had taken chalk with me when I went down into the sewer just in case something happened and I didn't know how to return). I reached the manhole cover from which I had entered, next to the "King of the Blackmailers." I returned because that was the closest exit and also because there, I could change my clothing. Try to imagine what I looked like and how I smelled after this little jaunt through the sewers…I told the ten remaining people that I would be in contact with them. They asked me whether I had this and that; I told them I had everything I needed to get them out. What was I going to tell them, that I had no plan, nothing? That I didn't know what I was going to do once I left the sewer? I just told them to wait and that I would make contact…I kept my promise. Before morning I came back and made contact. Every manhole has a small opening of about 2 centimeters. I passed a note through the opening and I asked them to let me know whether everyone who had remained in the ghetto had reached the sewer, and whether they were all now waiting at that spot. I got an affirmative answer that everyone was waiting there, and that I had to get them out immediately because if I didn't take immediate action, there would be no one left to save. I knew it was the truth, but I had no possibility of acting so quickly. In the meantime, during the night, I lowered some food down to them. I couldn't give them any clear answer, because I didn't know when I would be able to arrange some way, some vehicle…where was I going to get a vehicle that could move all those people? After a lot of running back and forth, I managed to arrange to rescue them from the sewer on May 10th, in the middle of the day, at a distance of 150 meters from a German guardpost.

Why was the rescue planned for that specific time and place?

Because of that same "King of the Blackmailers"; he lived there and that provided us a way in and out of the sewer. In the meantime he was cooperating, and we took advantage of that. The hour of the rescue operation had to be during the day because at night there was a curfew and it was impossible to move around in the streets, and also because we had arranged for a truck that moved furniture, as though we were moving the contents of a house. We ordered two trucks but in the end only one showed up, and suddenly the driver saw that instead of furniture we were loading people… And in all the confusion a Polish police officer passed by and started walking in the direction of the Germans. I went over to him and told him that this was an operation by the Polish underground and I asked him to go back to where he had come from… In retrospect this was foolish, because he could have reached the Germans from a different direction. But I wasn't thinking…I was thinking only of preventing him… We opened the manhole and people began to emerge and to climb into the truck…they were at the end of their strength and every one of them had to be helped out of the sewer; we had to pull them out. The truck was filling up and when I saw that there was no one else coming out of the sewer I went over to the mouth of the sewer, bent over and yelled into the sewer, "Is there anyone else there?" No one answered. And I gave the order for the truck to move.

Did the Germans see all this?

They saw that there was some kind of commotion but they didn't come over to check; they didn't take any action. Their job was to stand there, and so they stood there. Whether they saw or not, I don't know.

How many Jews climbed into the truck?

I think that in the truck there were…it was so crowded…they were lying on top of each other. The commander of my area in the ghetto, who was responsible for a number of fighting groups, also climbed into the truck – Marek Edelman. The truck was full. I gave the order to move. And here something happened that put me in an extremely difficult position: I gave the order to move out, and Zivia Lubetkin, who was among those who climbed into the truck, said, "There are still people down there, wait." And I told her, "Listen, I am the commander of this operation," in those words…"I'm not waiting. Otherwise no one will get out of here alive." And I gave the order to move, and that was it.

[NOTE: In an interview with Kazik at Yad Vashem in 1959, he related the following: When we reached the forest, Zivia told me she was very angry and that she was going to shoot me. I said it was fine with me; we would just shoot each other. I was told afterwards that inside the sewer, when the manhole cover was opened and people began leaving, two people were sent to call those who had gone into a side branch of the sewer. The two refused. Zivia turned to Shlomo Shuster and Adolf Hochman and sent them [to get the rest of the people]. She promised them that she wouldn't move without them. By the way, Shlomo was my closest friend.

Despite all this, when I look back with the perspective of the many years that have passed, I am sure I did the right thing. The truck was full anyway, and there was no room for any more people. According to my calculations, the Germans arrived just a few minutes after we sped away from the place. I assumed that when the people who remained in the sewer reached the exit and saw that it was closed, they would understand that it was impossible to leave at that moment. My assumption was incorrect, because apparently they did try to escape from the sewer, and all were killed. When I asked why 15 people had gone into a side branch of the sewer and didn't stay together with the others directly under the exit, Zivia told me that under the exit the water level was very high and it was difficult to remain there. Some had to stay in a dryer place. The next day I made contact with Antek Zuckerman. I told him that Zivia was among those who had been rescued. He didn't believe it at first. Afterwards I took him to the forest and he met with everyone.]

I spoke about all this with Marek time and time again and I asked him, "Tell me, why didn't you get involved? You were my commander." What I can tell you is that he was also completely exhausted and wasn't able to do anything. But he answered me, "Listen, I thought that you were the only one who knew what he was doing there." That's right, there was no one else. Not that I asked to be put into this position. I didn't ask for a thing. I had no idea that I would be forced to make a decision like that. But we had to take action. Something else I understood was that every second that passed could have caused us to pay a very high price. We had to get these people to somewhere else, and there are no forests close to Warsaw. That was a big disadvantage, but there was no choice – that's all there was to it. I asked a friend of mine, who was with me there, to help with the truck so that we'd know where they went. I had to be able to find them afterwards – it was impossible to send them alone. But he didn't agree. So without a choice I jumped onto the truck and went with them, and we got to a little forest – a thicket actually. After about an hour and a half to two hours had passed, I thought, "It's time to go back to Warsaw, back to the sewer to see what's happening." And when I went back I saw that the guy who had been with me, the Jew, was already dead. I saw that he had been shot, and that there was another body lying there that had been shot. I understood that I had to get out of there because many people had seen me and someone could have pointed me out, and I would have been finished also…I got out of there.

What became of the people who were rescued from the ghetto?

In the end, we brought this group of people, I estimate about 50-60 people, to a different forest that was very far away, a thick forest that was really a forest. They stayed there until the end of 1944, beginning of 1945. I would come to see them in the forest, and there as well we had trouble with the Poles. Had the Poles known that this was a group of Jews, they would have murdered them. In the meantime, we were able to connect with the heads of the Polish underground in Warsaw and we got some help from them. They [the people who were rescued from the ghetto] sat in the forest for a long time. Some of them were killed in different operations. But during this period we took some of them out of the forest, we brought some of them to Warsaw, we hid some of them in hiding places, and some stayed in the forest until the end. We kept up the connection with them during all the years of the occupation – those who were in the forest and those who weren't.

This year we commemorate 70 years since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and uprisings in other ghettos and camps, and the subject is being taught in schools and emphasis is also being put on the subject of uprising in the groups that go to Poland. What is the main message, in your opinion, that the youth must be taught?

To be human beings. We walk on two legs – that's what I think and that's how I feel. Among the two-legged animals there are those who are worthy and those who are not worthy of being called "human beings."

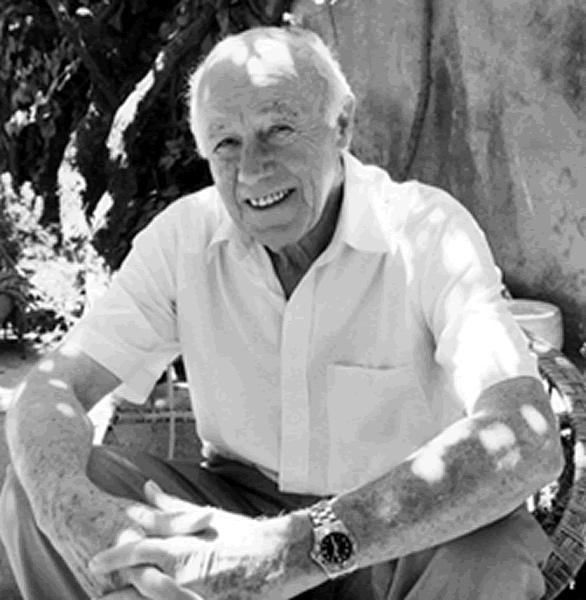

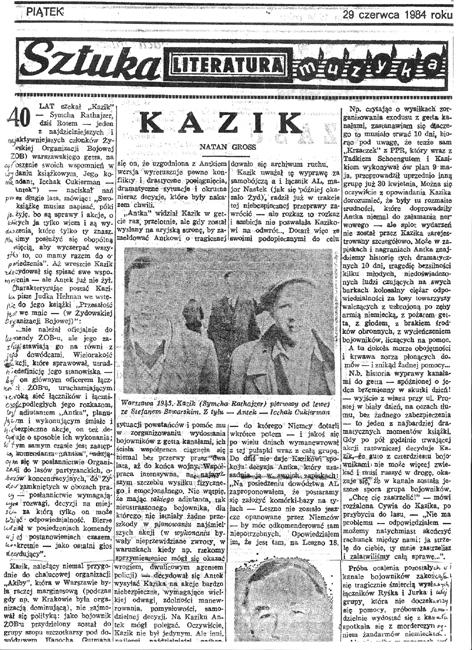

Editor’s Note

This is a short taste of the full story to be found in Kazik’s memoirs, which he was finally persuaded to set down on paper, nearly forty years after the events. The book is called: Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter. The Past within Me, by Simha Rotem (Kazik) translated from the Hebrew by Barbara Harshav and published in1994 by Yale Univ. Press (New Haven and London). The interview text above was compiled from a number of lectures and interviews of Kazik. These are: his short account of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising written while still in Poland during the war and sent clandestinely to Palestine on May 24, 1944 (this account was translated from Polish into Hebrew and appears in a book by Melekh Neustadt, Destruction and Uprising of the Jews of Warsaw, published in 1946); testimony at Yad Vashem in August, 1959; and a lecture given to Yad Vashem employees in October, 2012.