Dr. Michal Unger

The following are excerpts from a wide-ranging discussion with one of the leading researchers of the Lodz ghetto, Dr. Michal Unger, held in October, 2014.

The year 2014 marks seventy years since the Lodz ghetto was finally liquidated by the Germans late in 1944. The liquidation came in the final gasps of the Nazi dream of establishing the German Reich of a thousand years. Since Lodz had the second biggest Jewish population to be incarcerated in a ghetto, it provides a veritable laboratory situation in which the behavior of masses of people living in extreme duress can be examined over a period of more than four years. The reader of the following article will find himself immersed in the findings of a leading researcher’s insights into the human difficulties and pain experienced in the ghetto of Lodz for the four years of its existence.

The first subject that Dr. Unger clarified for us was the number of Jews involved in the narrative of the city before and after the formation of the ghetto.

Dr. Unger:

Before the outbreak of war, one third of the population of Lodz was Jewish; that is, 233,000 Jews out of more than 670,000 people. From the beginning of the war on the 1st of September, 1939, and until the ghetto was closed, about 77,000 Jews fled eastwards, many to Warsaw. I estimate that about 180,000 Jews were finally closed into the ghetto although the official German estimate was about 164,000. So with the formal closing of the ghetto on the 1st of May, 1940, about twenty thousand Jewish refugees had streamed into Lodz which somewhat offset the big exodus. It must be understood that there was tremendous pandemonium of population movements in all directions. Many Jews did not participate in the German population census of the city and this also contributed to the lower German figure.

Artur Greiser and Hans Biebow, the two top German personalities of the Lodz ghetto, had over the four years of its existence managed to turn the ghetto into a lucrative source for lining their own pockets and furthering the German war economy. Greiser was the Governor and head of the Nazi party in The Warteland, the biggest province in western Poland annexed to the Reich and Lodz, the biggest city in this area. Biebow was the head of the German ghetto administration in Lodz. The different industries that operated in the ghetto supplying the German war machine had transformed Lodz into a veritable labor camp and these two men were responsible for ensuring that Lodz would remain the last standing ghetto into the autumn of 1944. In this regard, they cannot be suspected of having Jewish interests at heart but rather the continued economic activity of the ghetto, which they had become experts at milking. So much so that they succeeded in postponing Himmlers’s plan for an earlier liquidation of the ghetto.

Unique Aspects of the Lodz Ghetto

There were about one thousand ghettos in which the Jewish population of eastern Europe was incarcerated. The ghetto stage should be seen as a holding operation in which the Jews were concentrated in small areas of towns and cities from which the Germans could then transfer them when they were ready to move on to the next stage. We asked Dr. Unger to point out ways in which the Lodz ghetto differed from other ghettos.

Dr. Unger:

There are several points here to be taken into consideration.

Jewish Forced Labor

The main point that contributed to Lodz being the longest surviving ghetto was undoubtedly Jewish forced labor.

The German administrator of the Lodz ghetto mentioned above, Hans Biebow, who had been a coffee merchant in Germany before the war, discovered that exploiting Jewish labor could contribute enormously to the German war economy and simultaneously line his own pocket. He persuaded his superiors, especially Artur Greiser, the powerful and ambitious Nazi administrator of the whole region, of the ‘worth’ of Jewish labor and hence both together maneuvered to maintain the ghetto in the face of Nazi designs to liquidate it earlier.

Biebow was successful in organizing massive work orders from the German military machine and private orders from Germany, turning Jewish labor in the Lodz ghetto into a veritable goldmine. In the last two years of the ghetto we see the Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer, a figure very close to Hitler, actively pushing Greiser to maintain the ghetto because of the worsening war situation and the lack of workers in the Reich. Thus we see how Lodz featured centrally in the deliberations and planning of the very top officers of the Reich.

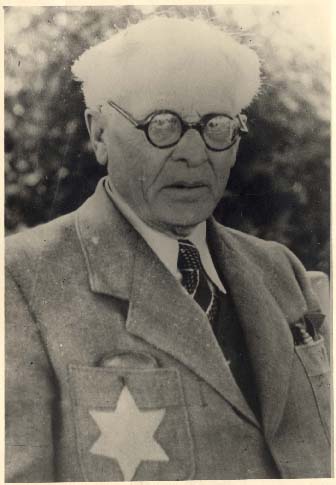

This German work policy was implemented through the coerced participation of the Head of the Jewish Council, the Judenrat, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski. He was the Head of the Council from before the beginning of the war until the final liquidation of the ghetto in 1944. The interaction of Biebow and Rumkowski, the German and the Jew, was crucial in the unfolding of the Lodz chronicle.

It must immediately be emphasized that Rumkowski’s motives were completely different to Biebow’s.

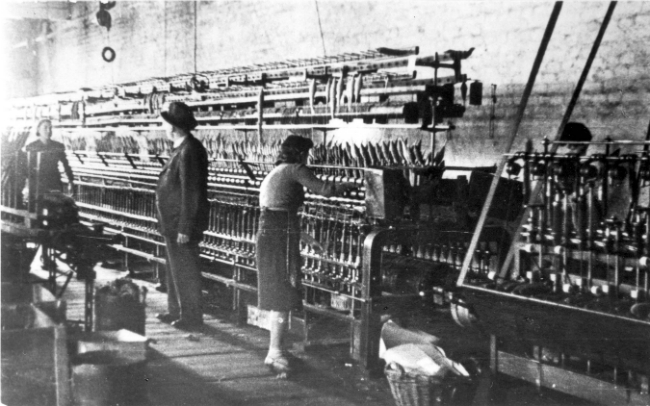

With his highly-tuned organizational abilities, Rumkowski helped turn Lodz into a huge labor operation for the Germans with more than 90% of the Jews working in one hundred industrial enterprises from textiles to weaponry and even to airplane parts. He implemented his work program in pronounced dictatorial style but Rumkowski's underlying motivation had a dual purpose:

- In the first stage of the ghetto, every Jew working in the ghetto was contributing to the ghetto's purchase of food from the Germans, illustrating his concern with the continued supply of food to the starving ghetto.

- After the start of the "Final Solution" in the ghetto in January 1942, every working Jew was, by virtue of his work, a bulwark against deportation to a death camp.

This double-headed strategy existed in other ghettos but the unique aspect in Lodz was the fact that it dovetailed with the German rapacity and military interests outlined above. This German interest was paramount in turning Lodz into the longest surviving ghetto and should not be attributed to Rumkowski's strategy.

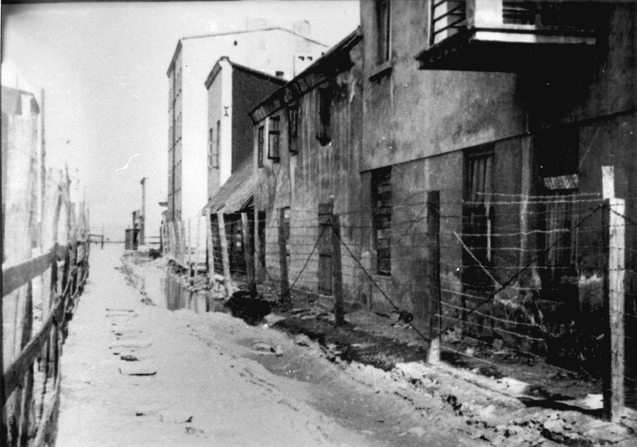

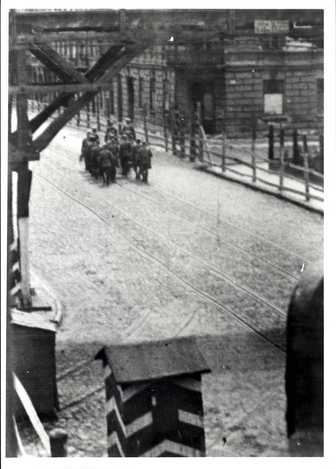

The Isolation of the Ghetto

Lodz was almost totally isolated from the rest of the city and from the world. There were no escape routes, and there were no sewers through which any smuggling could be conducted, as in Warsaw. The German guard system was so effective that virtually no one entered or left the ghetto illegally. This isolation led to extremes of deprivation both as regards food supplies and needless to add, any medical supplies. The general absence of smuggling, which was very often a life-line in other ghettos, brings us to the statistic of about 44,000 deaths – 21% of the ghetto population within the confines of the ghetto. This represents the highest mortality rate in all the ghettos. This isolation had a further devastating consequence for the ghetto population: the total lack of information from outside. For the majority of the Jews transported from the ghetto to the gas chambers, their imminent destiny remained unknown until their last moments. This fact is crucial in understanding why there was no revolt in Lodz as there were in several other ghettos.

Youth Movements and Resistance

We asked Dr. Unger to widen the canvass on the youth movements in the Lodz ghetto. The youth movements were the main factor in the revolts that were organized in other ghettos. The famous Warsaw ghetto rebellion in April 1943 organized and carried out by young people from the youth movements, most of them in their teens and early twenties, was unprecedented in terms of civilian resistance anywhere in Nazi-occupied Europe. In light of this, the second biggest ghetto with highly organized youth movement activity begs elaboration. Specifically, Dr Unger related to the fact that there was no rebellion in Lodz.

Dr. Unger:

The leaders of the youth movements in Lodz, and remember that we’re talking about young people in their early twenties, were overjoyed to hear of their comrades' rebellion in Warsaw. They were filled with pride at the immense courage displayed by their friends involved in this confrontation. Yet it was clear to them that there was zero possibility of achieving the same in Lodz for the following reasons:

- The strategy of saving people through labor belonged to all strata in the ghetto. In April 1943, Warsaw was facing its final liquidation by the Germans. In contrast, Lodz was bustling with production for the German army and Hans Biebow was moving full steam ahead in maintaining the economic necessity of the ghetto. The youth leaders were part and parcel of this reality and hopeful that as a result of this very different situation, the ghetto would survive. Hence, a rebellion would be counter-productive. It should be noted that usually the rebellions happened in the last stages when the ghettos were being destroyed.

- As Lodz was in the western reaches of Poland annexed to the Third Reich, a Polish underground was suppressed in this Reich territory. In Lodz, the Polish underground was fighting for its own existence and helping Jews was not a priority. This meant that the isolation of the ghetto was virtually hermetic with no possibility of smuggling weapons into the ghetto, as distinguished from Warsaw where there was some contact with the outside.

- The extreme hunger in the ghetto had a major debilitating effect on day-to-day life for all those trapped inside, including the young members of the youth movements. Thus their energies were directed more at sustaining life through various activities and ameliorating living conditions. This was spiritual resistance, known also as "amida" (Hebrew) and its importance was highlighted by the fact that hope was generally on the wane.

- In Lodz, in the summer of 1944, they knew that the Red Army was advancing in Poland and the youth leaders hoped that liberation would precede liquidation. The pendulum swung between hope and despair, entangling all in the complexities of this ‘waiting game’.

Cultural Activities

In any discussion on life in the ghettos, the question of literary and cultural activity is of special interest. This sphere of human endeavor, with all the physical hardships endured in the ghetto, presents an added dimension to the term ‘resistance’ just discussed above in the context of the youth movements.

Dr. Unger:

In Lodz, the head of the Jewish Council, Rumkowski and his administration, influenced and organized the public cultural activities, as in all other spheres of life. He decided what music would be heard and what plays would be staged in the Cultural Center that he established. Open criticism of Rumkowski was dangerous and in one case he was dissuaded only at the last moment from expelling a writer who had dared to cross him openly.

The positive side of this was that the musicians and actors were paid by the Judenrat. This was not the situation in other ghettos where people from the art world were starving to death.

There was a great demand for cultural activity and people bought tickets sometimes at the expense of a meal. This afforded them a glimpse of the earlier normality in their lives and can also be seen as an expression of spiritual resistance.

There was also private literary and musical activity in Lodz but such meetings were held in the homes of the writers and musicians. The effective presence of the literary circle in ghetto life was less felt than is evident from the attendance of the ghetto population at musical concerts that were held at intervals in the ghetto.

However, a well-organized archive was maintained in the ghetto and much of it was hidden and retrieved after the war. Thus literary output during the ghetto has contributed much to the portrayal of ghetto reality for the generations after. The semi-official activity of the archives has added dramatically to our knowledge of ghetto life in all spheres. For example, daily reports of ghetto activity were recorded in what is published today as the Lodz Chronicles. Many diaries were written by people in the ghetto and these present a devastating picture of deprivation and suffering. These diaries are yet another example of spiritual resistance.

In concluding the interview, Dr. Unger impressed upon us the open-ended nature of revealing the sad history of the Lodz ghetto. She pointed out that new books are appearing all the time, elucidating different aspects of life and death in the ghetto. Both Polish and German historians are prominent in this endeavor.

In addition, Dr. Unger indicated that the municipality of Lodz has invested much effort in improving the areas of the erstwhile ghetto thus facilitating access of visitors to different areas of the ghetto. She added that the Lodz municipality is active in educational efforts to mark the contribution of Jewish life to the city of Lodz before the war. Lodz officials invest great effort in maintaining the Jewish cemetery in the city, one of the biggest in Poland.

The Holocaust succeeded in ending a vibrant Jewish community in Lodz but through the valuable work of Dr. Unger and her like-minded colleagues, and together with the efforts of the Lodz authorities, we today have improved access to what was Jewish life in Lodz.