My colleague Liz Elsby and I sat down to interview Samuel Willenberg on Sunday, December 4, 2011 in his apartment in Tel Aviv, Israel. His wife, Ada, herself a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto, sat with us, plied us with tea and pastries, and added to our knowledge and to the discussion.

Samuel was born in 1923 in Czestochowa, Poland. When the Germans invaded Poland he was 16 years old, but he enlisted in the Polish Army in order to fight against them and was wounded severely. His family moved to Opatow for a time. In the fall of 1941, while hiding from the Germans, his two sisters were arrested in Czestochowa. His parents managed to survive in Warsaw with false documents. Samuel himself was taken together with the Jews of Opatow to Treblinka, when the Opatow ghetto was liquidated. He spent about ten months at forced labor in the Treblinka death camp, and participated in the revolt there on August 2, 1943. Later, Samuel joined the Polish underground and took part in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. For his bravery he was awarded the Virtuti Militari medal, the highest military commendation in Poland, and the Komandorski Order of Polonia Restituta. He made aliyah to Israel in 1950.

Treblinka was the most lethal extermination camp of Operation Reinhard, where approximately 870,000 Jews were murdered during the thirteen months that the camp was in operation, from July, 1942 through August, 1943. Currently it is believed that there are only two survivors of Treblinka who remain alive in the world: Samuel and Kalman Taigman.

Samuel has created a series of fifteen sculptures that are scenes from Treblinka. They have been displayed in Germany, in Poland and in Israel.

Samuel, where did you learn to create art?

My father was an artist – I guess I have the genes.

Did you draw when you were a child?

My father was a painter. My mother didn’t allow me to pick up a pencil - she didn’t want me to be a poor artist!

So you never learned to draw? It came to you naturally?

Yes.

In the camps, did you ever think about art?

No. In the extermination camps I didn’t think of art; the sculptures I did later, after the war.

My artistry is my memory – my ability to remember what my eyes saw… I remember pictures. I see the pictures from “there”, even today.

How did you start sculpting?

When I retired1, I took courses in art at a local university in Tel Aviv (“University Ammamit”) . I began with painting but I decided to sculpt.

The sculptures that you sculpt, are they connected to what you experienced? Do they somehow “translate” pictures that you have in your head?

Yes! When you see my sculptures – you see Treblinka.

When you do a sculpture, would you say that you sculpt more for the purpose of making art or for the purpose of documentation, in order to document what happened?

Definitely for purposes of documentation.

The first sculpture I did was the “Scheissmeister”2.

Why was that the first?

Because it’s a symbol of German cynicism, a symbol of EVERYTHING. [Samuel says this through clenched teeth]. With the clothing of the hazzan3, with the clock, because of this I did it first…. He is screaming. He’s screaming to the heavens. But God is not there. There is no God.

Which sculpture do you think is the strongest?

Everyone thinks a different sculpture is the best. My wife likes the sculpture of the father helping the son take off his shoes. This is what happened right before they went to the gas. This is what the whole history of the Shoah looks like.

Can you tell us more about the sculpture of the little boy with the father helping him to take off his shoes?

Yes. You need to understand where this is happening - that it’s not just a father helping the boy off with his shoes at home – this is happening on the way to the gas chamber. That’s the explanation - it changes the whole meaning. The little boy is holding a string, because the “reds”4, the people with the red armbands on the ramp5, gave strings to the people getting off the train and told them to tie their shoes together.

… This scene with the boy and the father - I saw this happen. I was next to them. I saw the people that this happened to. It happened near a barrack. I saw it happening! Others were taking off their shoes, but by themselves. And then afterwards, I saw the scene always before my eyes. I still see these things today.

After you finish a sculpture, how do you feel?

After I finished the Scheissmeister, I felt like him – like the Scheissmeister. I relived the situation, I was part of him. That’s why he is screaming.

How did you feel while working on a sculpture?

When I was sculpting it was impossible to bother me, to talk to me, until I finished sculpting. I become the sculpture; I am inside it.

Ada: When he sculpted, he was “inside” it; he was agitated.

Samuel: But when I finished, I never felt relief. There is no relief! It never gets easier to bear. I only felt a kind of satisfaction.

Every time I made a sculpture, I saw the scene – I lived it. The scene with the boy and the father - I saw this happen. And then afterwards, the scene was always before my eyes.

So the sculptures tell your story instead of you?

Ada: Why instead of him? He tells his story, too – he has told it to groups in Treblinka more than 30 times. He talks to groups in Israel that come from all over the world.

How long does it take you to do a sculpture?

Each is different, but all the sculptures of Treblinka I did in 3 years. I don’t make all the details exact.

Do you still sculpt?

No, there wasn’t anyone to sculpt for. The Israeli newspapers didn’t even cover the exhibitions. I had a well-publicized and well-reviewed exhibition in Warsaw, though. In my exhibition in Warsaw, the caretaker wrote beautifully about my sculptures that they were “grotesque” and showed “the most tragic moments of extreme horror”; she wrote, “The tormented figures of the camp are returning back to life.”

Did you ever sculpt anything that happened to you after Treblinka?

No, only Treblinka. Treblinka was the most….

No, the rest is the history of Poland.

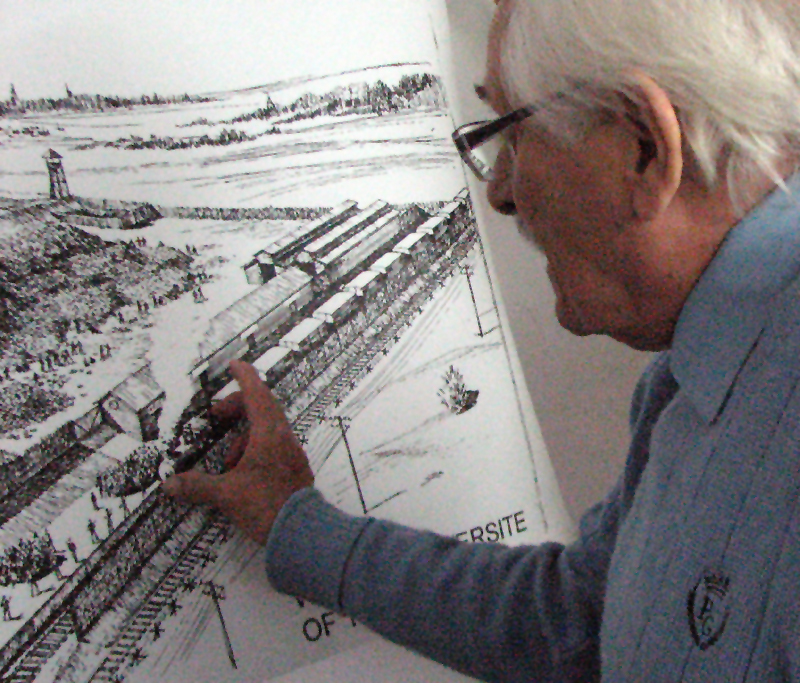

But I did create maps – actually drawings – of Treblinka. These were made on the basis of the measurements of the camp recorded in 1944 and published in 1946 in the first Bulletin of the Central Commision for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland, a commission created after the war by the provisional Polish government to take evidence of the crimes. I created the drawings in 1981, when my book first came out. Many models of Treblinka have been made throughout the world on the basis of these renderings.

Which sculpture was the most difficult for you to do because it involved the most painful incident for you?

The most difficult sculpture to do was the sculpture that I didn’t do. It’s the sculpture of when I discovered the truth about my sisters6. I wasn’t able to make this sculpture. Not at all.

Ada: He relives this incident all the time. On one hand, he is full of the joy of life. On the other hand, he still “sees” this all the time, he remembers.

Samuel: I return to it every single day – I live it, even if I don’t want to, alongside my day-to-day life.

What do you think of artists who make Holocaust art without having experienced the Holocaust?

This is normal – in every time, in every era there are artists who never see the incidents they represent in their art.

Do you think there are any limits to Holocaust art?

It depends on the artist. It depends whether history accepts the art. It depends on the trends – you can’t know in advance. Look at expressionism – the colors they used. Cubism. It’s the same thing – it’s normal.

There are sculptures with a lot of details, and there are those with less. Why is that?

I didn’t want to create naked women. But [in the sculpture of women on their way to the gas chambers, created in 2000] there are a lot of suitcases – because the Holocaust was not just murder, it was also robbery. And what a robbery!

Which sculpture do you feel is the most important?

There are two: the first is the sculpture of the uprising itself. It shows the heroism of the Jews in trying to destroy Treblinka7. You know, rebelling in a death camp was a very difficult thing. It was not easy to organize an underground – many prisoners were strangers to each other, and each was afraid of the other because there were informers among the prisoners who might tell the Germans about any conspiracy to revolt. It was a different situation than the uprisings in the ghettos, where there were youth groups and everyone knew each other, relied on each other and trusted one another. In Treblinka it was dangerous to let people in on the secret of the underground because this invited betrayal. I wrote in my book about a prisoner called Kronenberg, a journalist who had worked for Chwila, a Polish-language daily Zionist newspaper published in Lwow. He was entrusted with the secret of the uprising. One day he was caught by the Nazis for not working, and was taken to the Lazarett. As soon as he realized he was about to be killed, he tried everything to save his life, including telling the Germans that there was an underground in the camp, and promising to tell them everything he knew about it if they would only let him live.

In the sculpture of the revolt you can see the young boys who removed grenades, pistols and other weapons from the Nazi’s storeroom. One of them is handing over a grenade that was hidden in a bucket used for potatoes. These weapons were delivered throughout the camp. You can also see the overturned baby carriage used by my best friend in the camp, Alfred Boehm, to collect garbage. Alfred was the liaison between the boys and the rest of the camp. He was killed in the gunfire during the uprising – I found him slumped next to his carriage. I am the man on the right, escaping with a gun in my hand.

The sculpture of the escape is also important. It shows what happened when the prisoners in the camp tried to escape while trying to dodge gunfire from the Ukrainian guards in the watchtowers. The camp was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire, but also by anti-tank barriers. Many of the prisoners who tried to escape were killed while trying to climb over the wires, and in order to escape I actually had to climb over the bodies of my friends who were killed

there8. I was wounded in my foot during the escape.

Can you tell us the story of Ruth Dorfmann?9

I was not a frissiere (barber)10; there was a group of barbers but I was not one of them. Suddenly a big transport arrived, so Kiwe, the SS-man, grabbed some of us to help. I wore the white robe, and I had the scissors, in the “jupa” – the hut that the Germans built. I cut her hair cleanly, for a reason. I did more than I had to – I made it a clean haircut, because if I had just cut randomly here and there, they [the women] would have understood [that the haircut was not for purposes of disinfection, as the Germans told them, but that they were going to be killed. –Ed.] I cut cleanly, as though with a razor, to make it smooth. For a reason. And this girl started talking. She had come from the Warsaw ghetto. She was beautiful. She was naked. And in the background there was fog, like mist, that was rising from the ground, from the warm clothing left on the ground, from the body heat left in the clothing, and maybe also because the women had urinated. They had just come from the big room where all the women were forced to take off their clothing, into a smaller room, through some doors. So in the background there was mist rising from the clothing. And she started talking. She said, “I am Ruth Dorfmann.” I remember! She said, “I have a diploma.” She had learned in the ghetto. She was about 20, my age.

How old were you?

I was 19, turning 20. I turned 20 in Treblinka.

And she was talking. She asked, “How long will it take?” She knew [that she was about to be killed]! They all knew!

You know, I made a sculpture of a painter who painted all the signs that were on the ramp. Why? Why? The Germans made signs: signs to Bialystok, a clock that didn’t really work. The Germans made it look like a real train station….11 And it really looked like one.

Tell the story of the sculpture of the girl from Warsaw who lost her mind and stood with the piece of bread.

Ada: You know, Samuel knows the stories of Treblinka. But in the Warsaw ghetto – I was there – there were people dying of hunger, there were people who committed suicide, there were people who went crazy. I was lucky that I was still a girl – maybe I didn’t understand everything. But a lot of adults went crazy.

Samuel: Some killed themselves.

Ada: Many people went crazy. So simply, around January 18th, when Ruth Dorfmann arrived on the transport, many of the Jews living in Warsaw already knew where they were being taken. By January there were already instances where people had escaped from the trains on the way to Treblinka and came back to the ghetto and told stories – and we didn’t want to believe them. Even today I can’t believe what went on in Treblinka, so how could they then? I was about 13 years old in the ghetto. I remember that there were those who came [back to Warsaw] and told that they had escaped from the train, or from the camp itself – but people didn’t believe them. And then those who did begin to understand – some of them went crazy, and others committed suicide. And this girl, she was one of those who went crazy.

Samuel: It was winter. There was a girl who got off the train, and just stood there. Everyone else went inside the yard – “Schnell, schnell, schnell, schnell!!” [“Fast, fast, fast!” the Germans yelled]…

Ada: And they went in towards the “Death Road”12.

Samuel: But this girl stood still. The barracks were just like the ones in Majdanek – they were actually stables for horses – just like in Birkenau. There were two prefabricated barracks standing together. Here there was an opening.13 And suddenly Miete of the SS – the “Angel of Death” – told the girl to move forward. We saw her entering the sorting yard. He nudged her forward into the yard, like a child rolling a ball forward. And suddenly she saw all the people, all the colors, the open suitcases.14

And we15 saw her. We stopped working and we all stared at her.

Ada: And she was dressed differently…

Samuel: You see that she was wearing high heels. She was dressed in all kinds of things she had probably found in one of the destroyed houses in Warsaw, where the people had run away at the last minute. And probably when they ran, they left shoes like this behind. They didn’t wear shoes like this!

Ada: I know – my mother was taken to Treblinka. And I know that every time we were called to assemble in a courtyard and rounded up for an Aktion, people wore layers of clothing – they wore as much clothing as they could. Because we believed we were being taken to a labor camp. So you wore a lot of clothing so that you would have a change of clothing – three dresses, several pairs of underwear. So people usually wore very practical clothing. And this girl…

Samuel: She was dressed like a ballerina!

Ada: She was dressed like for a ball. With the high-heeled shoes.

Samuel: And she was staring with these eyes – it was abnormal. She was clutching a piece of bread to her chest. It was something extraordinary.16

Where did she get the bread? Was it bread that was given out by the Germans at the Umschlagplatz17?

Ada: No, I don’t think so. When the Germans first started the transports from Warsaw, the miserable people in the ghetto who didn’t have anything to eat would go to the Umschlagplatz because there the Germans gave them bread and jam.18

Afterwards, the Germans already stopped with this.

Samuel: It wasn’t in the first days of the transports [so the bread she was clutching wasn’t given to her by the Germans]. It was December, 1942 or January, 1943 – around when Arthur Gold19 , the conductor from Warsaw, came.

You don’t understand. I saw people, pass by – artists. People you’ve never heard of. And they were killed in Treblinka. It’s hard to explain what art there was! Culture. Warsaw was culture!

Flaschensortierungkommando – the nickname for the group of Jewish prisoners collecting glass bottles to eliminate the signs of those killed at Treblinka (2000)

Tell us about the sculpture of Arthur Gold.

[The sculpture shows the trio of violinists that the Germans forced to play in the camp. They played popular prewar tunes. Samuel wrote that the tunes reminded the prisoners of years gone by, and “left us depressed and sore of heart. The Germans were pleased with themselves: they had succeeded in organizing an orchestra in the death camp.” Willenberg, p. 133].

Samuel: During the time of the exhibition of my sculptures in Israel, the Polish Ambassador came. I put a tape on the side, and while I explained the sculpture to the audience, I put on the music [of Arthur Gold]. I put on music and he cried.

Ada: You know why he cried – because my husband said, “We will stand here for a moment in memory of Arthur Gold. He isn’t alive anymore, no one remembers him, he has no grave, so we’ll stand here for a minute and listen to his music.” And the ambassador cried.

Samuel: You know why they dressed the orchestra like this20 ? So that the SS-men could make fun of them, and could laugh at them. To show them that they were nothing, that they were not men. To make them into clowns. This made it easier for the SS to kill them – it’s much easier to kill if it’s not a human being that must be honored.

What about the sculpture of the man with the baby carriage?

Ada: You know that the Germans had a special department, the Flaschensortierungkommando.21 Before the war there was no plastic, so everyone had glass bottles that they used in order to bring things with them – medicines, everything. And suddenly the Germans made a special work detail – a detail that collected all the bottles – they did this because glass remains in the earth and doesn’t disintegrate for thousands of years…

Samuel: The Germans were afraid that someone would find all these bottles, in the middle of the forest, and get suspicious: where did so many bottles come from? So the Germans made a new department to clean up all the glass.

What is the sculpture of the man without the leg?

Ada: This sculpture is of a German war veteran from WWI who lost his leg. He thought that if he came to Treblinka with all his medals, that he’d get some kind of special treatment, but they killed him just like they killed all the other Jews – they killed him in the Lazarett with a bullet because he couldn’t walk.

And the sculpture of the stretcher?

This is the group that had to clean the cattle cars – they took the corpses out of the trains at the time that the trains arrived. They were called the “Blues.”22

We are indebted to Samuel, and to Ada, for sharing their time and their insights with us and for allowing us to see Samuel’s wonderful sculptures, which bring the scenes of Treblinka back to life.

- 1.Samuel was, for many years, chief surveyor in Israel’s Ministry of Construction and Housing.

- 2.The Scheissmeister was a prisoner put on duty to guard the latrine, so that no prisoner could spend more than two minutes there. As Samuel himself says in his book, “When the Germans noticed that the prisoners were going to the latrine too often and spending too much time there, Lalka [Kurt Franz, one of the SS men who later became the camp Kommandant, nicknamed “Lalka”, which means “doll” in Polish, for his “baby face” - Ed.] ordered the Vorarbeiters [sic] [Jewish foremen of a labor detail] to go to the storeroom and procure two rabbinical black suits and a couple of black hats with pompoms on them. Two prisoners were equipped with whips and ordered to don this getup. It was their job to make sure no more than five prisoners entered the outhouse at any one time and that they spent no longer than one minute inside. Alarm clocks dangled from their necks on strings. They were called the Scheisskommando – the “Shit Detail”. The Germans enjoyed their joke raucously….” Samuel adds that the Germans purposely made the prisoner who was the “master” of the Scheisskommando look ridiculous. “It was incredibly humiliating.” Samuel Willenberg, Revolt in Treblinka (Warsaw: Jewish Historical Institute, 2008), pp. 135-136, 273.

- 3.A hazzan is the cantor who sings liturgical music in a Jewish synagogue.

- 4.The “reds”, or the Transportkommando, were among the few Jewish prisoners who were kept alive in order to work for the Germans at Treblinka. A group of “about forty prisoners was engaged in the activities carried out on the square where the victims undressed. They directed the victims, relayed the German orders to undress, and distributed string for tying shoes together so they could be easily reused in the future without having to sort them….In Treblinka this team wore red armbands and became known as ‘the reds,’ or, in the prisoners’ special slang, the ‘burial society’ (Chevra kadisha).” Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), p. 108.

- 5.By “ramp”, Samuel is referring to the train platform at Treblinka onto which Jews from all over Poland and a number of additional countries, as well as about 2,000 Sinti and Roma, disembarked from the cattlecars and entered the camp to be exterminated.

- 6.Samuel’s sisters were murdered at Treblinka. He became aware of this when, as he was sorting the possessions of Jews in the sorting yard at Treblinka, he found a small brown coat that had belonged to his little sister, Tamara, who was five years old. A skirt worn by his older sister Itta was clinging to the skirt, “as if in a sisters’ embrace.” Samuel was able to recognize the coat as his sister’s because his mother had lengthened its sleeves with bits of green cloth as his sister grew. Willenberg, Revolt in Treblinka, p. 72.

- 7.he uprising at Treblinka took place on August 2, 1943. As Samuel writes in his book, “It was a singular and unique day, one which we anticipated and hoped for. Our hearts pounded with the hope that maybe, just maybe our long-nurtured dream would come true. We harbored no thoughts of ourselves and our lives. Our only desire was to obliterate the death factory which had become our home.” Willenberg, Revolt in Treblinka, p. 180.

- 8.Samuel described the scene as follows: “The machine gun stepped up its bursts. Behind me, at the outer fence, tragedy. The brave ones climbed up the iron and wire complex only to be hit there by a bullet. They fell with screams of despair. Their bodies remained hanging on the wires, spraying blood on the ground. No one paid any attention to them. More prisoners climbed over the still-quivering bodies and they, too, were cut down and fell, their crazed eyes staring at the camp, which now looked like a giant torch…I crawled through the open area and reached the barriers….The dead had created a sort of bridge over the barbed-wire complex across which another escapee moved every moment…With a leap, I climbed the bridge of bodies. I heard a shot, felt a blow – but another jump, and I was in the forest….” Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, p. 292.

- 9.The sculpture of the girl whose hair is only partially cut is connected to the story of Ruth Dorfmann. The events that Samuel describes here occurred in mid-January, 1943, when transports from the Warsaw Ghetto began reaching Treblinka every day after a letup of several months. At that time, Samuel was working in the sorting yard, sorting and packing up the personal effects of murdered Jews.

- 10.A group of ten to twenty men in the camp were forced to cut the hair of the women immediately before they were sent to the gas chambers. Samuel generally worked in the sorting yard, but in the incident he is speaking about, because of the size of the transport, extra men were needed to cut the women’s hair. Haircutting in the Operation Reinhard camps began in September or October, 1942, after the SS Main Office for Economic Affairs and Administration issued an order dated August 16, 1942 that provided, “care is to be taken to make use of the human hair collected in all concentration camps. This human hair is threaded on bobbins and converted into industrial felt. After being combed and cut, the women’s hair can be manufactured as slippers for submarine crews and felt stockings for the Reichsbahn.” Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, p. 109.

- 11.Samuel is referring to the German’s blatant and painstaking use of signs (including other signs for “First Class Waiting Room”, “Second Class Waiting Room”, “Ticket Booth”, and so on), and other means of deception on the ramp to fool the arrivals at Treblinka into thinking that they had reached a harmless, pastoral train station in a transit camp and would be showered and sent on to labor camps. Victims were to be deceived until the very end.

- 12.The reference here is to the path taken by most of the people who arrived at Treblinka: they were taken and forced to undress, women had their hair cut, and then all were sent to the gas chambers. The Germans cynically referred to the path to the gas chambers as the Himmelstrasse – the road to heaven. Prisoners more realistically called it Death Road.

- 13.Samuel indicated, on the sketch of Treblinka that he drew in 1981, a space near the rear gate between two huts that abutted the train platform. This was not the way most prisoners were led into the camp; they went in through the main gate and never saw the sorting yard, which would have revealed all the secrets of Treblinka and given them clues that Treblinka was a death camp. This was purposeful deception by the Germans.

- 14.The reference here is to the plundered Jewish property. Suitcases were opened on the ground for sorting, and there was what Samuel himself describes as a “towering multicolored mountain” of property in the sorting yard. Willenberg at p. 79.

- 15.Samuel is referring to the prisoners working in the sorting yard, sorting through the possessions of the murdered Jews.

- 16.In his book, Samuel finishes the story of the girl: “Like an apparition from another world, she approached the sorters one after another, glancing at the contents of the suitcases as if she were visiting a market at a sidewalk of street peddlers. She wandered among us, showing us a gentle smile and terrified eyes. Stopping at one of the suitcases, she withdrew kerchiefs of various colors and flung them into the air, as if dancing. Work came to a halt; everyone contemplated this strange specimen of colorful Warsaw misery….Suddenly her skinny face froze with fear. Terror seized her from top to bottom, driving the madness from her….She contemplated us with the fear of a person who, with the intuition of an animal, senses that her end is near.” Miete propelled the girl toward the area of the sorting yard near where an innocent fence with interwoven pine branches camouflaged the Lazarett – the so-called “field hospital”, also disguised with a Red Cross flag. In the Lazarett, prisoners who couldn’t walk or would have held up the extermination process were killed with a gunshot to the back of their heads. The girl from Warsaw was killed this way in the Lazarett. According to Samuel, the workers in the sorting yard paid the little girl from Warsaw their last respects when they heard the gunshot. Willenberg, pp. 77-79.

- 17.The deportation area where the trains left with their human cargo.

- 18.This was a ruse used by the Germans to get unsuspecting, starving Jews to volunteer for deportation.

- 19.Arthur Gold was a well-known conductor of popular music, like waltzes and tangos, that was brought from the Warsaw ghetto and murdered in Treblinka.

- 20.In his book, Samuel describes the clothes the Germans forced the musicians to wear. “They ordered our tailors to sew jackets of shiny, loud blue cloth, and to attach giant bow ties to the collars. Dressed not as prisoners any longer but as clowns, they provided entertainment after roll call, day in, day out. …The music was usually accompanied by the tenor of the crane engine. The diligent machine kept on exhuming and relocating corpses in the death camp even after 6:00 p.m., for the Germans had decided to expedite the matter of covering all traces and burning the bodies. The moment the concert ended, the SS-men ordered us to march toward the entrance to the hut….”

- 21.Translated, the Bottlesorting Detail. The baby carriages and strollers of the children who were murdered at Treblinka were used by this work group to collect bottles, thermoses, jars and aluminum containers. Children’s strollers were also used by the prisoners to collect garbage.

- 22.“This group of forty to fifty prisoners worked at the train platform. The team’s job was to open the freight cars and transfer the orders of the SS man in charge to disembark from the train. After the victims disembarked, the team workers removed the bodies of those who had died en route and transferred them to the burial ditches. Then they cleaned the cars and removed any remaining belongings to eliminate any traces of the transport cargo. Two or three prisoners would clean each freight car, and within ten to fifteen minutes the entire train had been cleaned. In Treblinka the platform workers’ team wore blue armbands, and thus were known as “the blues.” Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, at p. 108.