Yehuda Bacon

Yehuda Bacon was born in Moravska Ostrava, Czechoslovakia on July 28, 1929, into a traditional Jewish religious family. His father, Israel Bacon owned a leather factory. He lived with his mother, Ethel and his two sisters Hanna and Bella. In 1942, when he was 13 years old, he was deported to Terezin (Theresienstadt), where he studied with the artists Otto Ungar, Bedřich Fritta and Leo Haas. In 1943, he was deported to Auschwitz where he stayed for 6 months in the “Family Camp” in Birkenau. After 6 months most prisoners of that camp were murdered. Bacon, however, was among a group of teens kept alive as forced laborers in Birkenau. They were part of the "wagon commando" (Rollwagenkommando) and their task was to transport wood and other goods from place to place. In his job Bacon had access to the different areas of the camp. Most of Bacon's paintings depict events he witnessed as a teenager in Terezin and Auschwitz.

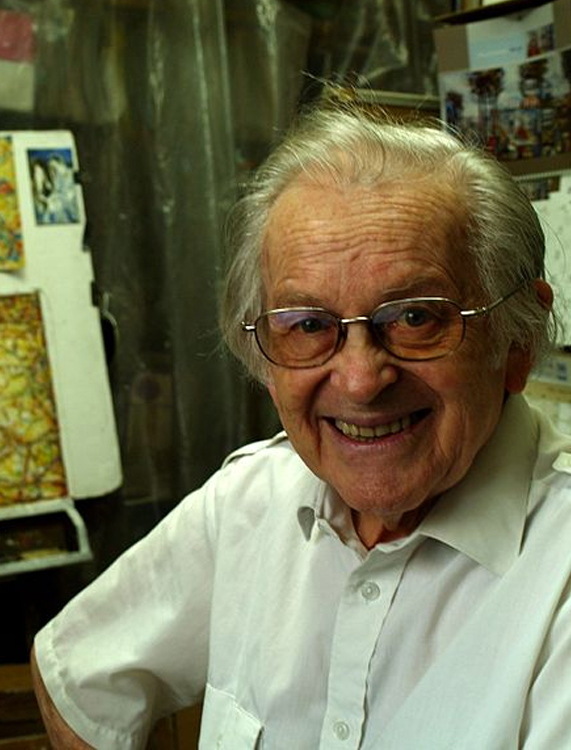

We met Artist Yehuda Bacon for an interview about growing up in the shadow of death in Terezin and in Auschwitz, about the rehabilitation period after the war, and the effect these had on him as an adult. The interview incorporates parts of the testimony he gave to Yad Vashem in 1959.

"The deportation was horrible… It happened like this: They got big cars, and neighborhood after neighborhood was cleared of people who were then taken to a gathering point. For us kids it was a novel situation when we suddenly arrived at the gathering point. We were inspected by Gestapo officers, and our identification cards were taken and stamped as either ‘confiscated’ or ‘sent’ […].

When we got to Terezin, a strange new world unfolded. We, the children, thought it was funny to see so many people wearing armbands, and army-like hats bearing the letters GW (Ghettowache, ghetto watch). It was as if we went abroad for the first time, where you see unusual uniforms […]. The whole atmosphere was extremely tragic. The total chaos, living on the roof under appalling conditions, searching for the luggage, the first separation from parents, sometimes for no longer than half an hour or an hour, but we still felt as if we were torn from our parents.”

[Taken from Y.B.’s testimony at Yad Vashem.]

The population of the Terezin Ghetto consisted mainly of Jews from Czechoslovakia, but also from Germany, Austria, Holland, Denmark and Hungary. The ghetto was a transit campen route to the death camps. 155,650 Jews were deported to Terezin, and 34,000 of them diedthere. About 87,000 were sent from Terezin to concentration and death camps in Poland, where most of them were killed . On May 9th, the Red Army liberated Terezin Ghetto. At the time, there were 30,000 Jews in the ghetto, mostly prisoners that arrived after the death marches. Only 3,000 of the Jewish prisoners of Terezin survived the camps.

The Terezin Ghetto was built in a fortified city formerly used as barracks by the Czech army. The deportation of the Jews created immense overcrowding in the ghetto. Men and women were separated and lived in different barracks, which meant families didn’t live together. In order to improve the living conditions of the children the Jewish leadership initiated the transfer of some of the children to special quarters (Heim) built in public buildings. At the Heim the children received an education, larger food portions and were under the care of counselors round- the- clock. Out of 15,000 children who were imprisoned in the Terezin Ghetto, only 150 survived the Holocaust.

In your testimony you speak about being deported to the Terezin Ghetto, and about how you lived with the adults before being moved to the children's quarter. How did you get there?

It wasn't a special place for the elderly, they just huddled everybody together in an attic. It took them time to separate everyone, maybe two weeks or a month. In the meantime all were kept together in the attic. Afterwards they separated the people according to different categories: sex, age and physical condition; men and women, old and sick. As for the youngsters, not all children were placed in Heims since these places had limited space. Many children who lived in the ghetto were with the older people most of the time in hard conditions. The lucky ones who got into the Heims lived under much better conditions, but they were the minority. I want to point out that not all children received this treatment, and people don't know about them.

What was the purpose of thedivision?

There was no division, It was simply impossible to fiteveryone. For example, they had one building for boys aged 10 to 14 or 15, who spoke Czech, and a separate one for girls of the same age and language background. And another building for German speakers, again divided into age and sex. That means that there were four buildings for Czechs and Germans, while other kids lived with the mothers or the elderly. Not everyone got to go the Heims.

It should also be understood that if someone got to be in the Heim, it didn’t mean he or she would always stay there. There was migration – sometimes children would be sent on transports, and there was a constant fear of the next transport. It wasn't regular. There were periods without transports - several months when the Germans made sure there weren't any to quiet things down, and then, suddenly, they resumed again.

Was the separation of the children, the founding of the Heims, initiated by the chairman of the Council of Elders Jakob Edelstein?

The Jews, as far as I know, had the authority to decide several things as if they were autonomous, even things like who would be sent on several of the transports. But they were directed by the Germans, who ordered them to include certain people on the deportation list, and to exclude others. The Gestapo had the final say and they gave instructions as to who goes to that transport. But to a certain extent the council of elders could decide who will be transported and who was on the lists, the prominent ones, who will remain in the ghetto. There was also some division within the council. There were the Zionists and Non-Zionists, the Non- Zionist Germans etc. Each one of the groups had lists of those that they wanted to keep. It was like in politics: there was always fighting over the prominent members, those who are allowed to stay, when you have to send 5,000 people, which ones stay? Also according to professions, there were those who couldn’t be sent, such as electricians who were very important for the ghetto, or experts and doctors etc., but overall the Germans were those who decided, they could veto anything of course, but the council had some way of influencing who would go and who could stay.

What was the children's status in those power struggles over the transport lists?

Children weren't a separate group, if they weren’t orphans they belonged to a family and usually the family, as a whole, was called to the transports. But there were exceptions, for example, if a child was sick or… There were cases where only the father was meant to be sent, but the mother wanted to join him in order not to stay alone… All sorts of cases that are hard to explain these days. Sometimes there was some freedom of choice within the family, but in other cases the Gestapo decided exactly who should go and who should stay.

In this matter, was there any difference between children who lived in the Heims and the others?

No. The children in the Heims didn’t have immunity. It's just that as long as they were there, they had much better living conditions. They got food that was a bit better, attention, they were able to study, not legally though, as there were no schools, but there were classes and some educational activity. The instructors taught several hours every day. Usually there was someone outside, so if an SS man would show up he or she could give them a warning. Fredy Hirsch was the head of the youth department. Do you know about the Bialystok children? They [the Germans] caught him when he tried to sneak in and sent him on a transport to Auschwitz as a punishment.

How long did you live in the ghetto?

Until the end of 1943, thanks to the chairman of the Council of Elders, Jakob Edelstein. His son was my best friend. I knew him since before the war from a Bnei Akiva community in a summer camp. And when I arrived in Terezin, I befriended him again and spent time in their apartment.

Several children's magazines like Vedem (We Lead) and Kamarad (Friend) were published in the Terezin Ghetto. Did you participate in this activity?

No. I spent a short while in dorm room 1, where Vedem was published. There were Petr Ginz and others who wrote the magazine. But I didn’t draw for Vedem. Later I was moved to dorm room 5 which was more Zionist whereas Vedem was more socialist. They were called "sky": the school of Dostoyevsky. That was just the nickname. Of course, I knew all the children. There is a book "All of Us Children?" [no English title found!] about dorm room 1.

Before the war you drew the usual things children draw like airplanes and such. When you entered the ghetto you started studying with artists such as Otto Ungar, Bedřich Fritta and Leo Haas. How did you get to know them?

I knew Ungar through my uncle. Unger was from Brno and my uncle Hersch Bacon was from Brno as well. He was a cantor and was prominent in the ghetto to some extent since he was one of the first people to arrive there. As long as Edelstein was there, my uncle was safe from transports, only later when the ghetto was liquidated he was deported to Auschwitz.

I knew Haas from Mährisch Ostrau, as he lived nearby. There was only one place where Jews could gather. The former school became a sort of a club. Jews were forbidden from gathering anywhere else. In this club they could still meet, play, etc. There I first met Leo Haas. He saw my drawings and gave me a few tips. I met him again in Terezin.

In the children's dorms there were different activities and contests in handicrafts and other fields, and once when I drew for one of them it caught the attention of several artists who came there, and they gave me private lessons. One of them was Ungar. Ungar was a former student of Willi Nowak. I studied with him after the war. Adler introduced me to Willi Nowak, who gave me recommendation letters for Max Brod and others.

What do you mean by "private lesson"?

Karl Fleischmann was head of the health department. He was a doctor and a very gifted poet. He also wrote a diary. After work hours, he invited me and offered his comments about drawings I showed him. I knew Fritta mainly through Edelstein as well as other artists who worked at the drawing workshop.

How did you get access to art materials such as paper, ink, paint andother such things?

The artists who worked in the technical department prepared the reports for the Gestapo. The reports arrived first to Edelstein's office and then he had to transfer them. There I got to know the rest of the artists. I saw the book that they brought to Edelstein's apartment. They, of course, had paper and all sorts of things since they made all the signs and ads in the ghetto: "Beware of Typhus. Wash your hand after leaving the bathroom!" and such. They painted some other Illegal paintings and hid them from the Gestapo. Only two of them survived the war: Haas and Ungar. Ungar passed away several months after the war.

As a child, were you aware of the status of these artists?

No. I knew they were painters. And I knew that I was favored, because I didn’t give anything in return for their lessons. They saw a gifted child. So they helped me.

Did you feel the need at the time to draw the difficult things you witnessed in the ghetto, or did you shy away from drawing them?

For me these were strange and unfamiliar things. It was a different reality. I looked behind the backs of others artists in the ghetto. I started with portraits of my friends. The drawings I took with me to Auschwitz were all lost, but others survived. I met the head of the Prague Museum in a convention at the Terezin House. He told me he saw five or six of my works. So I think they have some drawings of mine, I asked several times and they said they didn't, so there is nothing else I can do.

[On December 1943, Yehuda Bacon's family was deported on a transport to Auschwitz.]

"It was in December 1943. We left Terezin on December 5th, and probably arrived on the 17th. I think there were 2,500 people. Terrible scene. Horrible shouting: ‘Out!’, ‘Leave everything!’… Before that, right when we passed the Polish border we were in a war zone. Everything looked different, even the train engine sounded different. It was dark everywhere. It seemed as if the wail of the engine was ominous. When we arrived, we saw half-wild men in striped clothes. They beat us and shouted at us. Above there were anti-plane air balloons. They looked like fish. It was the first time I saw anything like that. It looked like an imaginary landscape, like a ghost story… We arrived at Auschwitz."[Taken from Y.B.’s Yad Vashem testimony.]

Can you tell us about your impression of the camp when you arrived? Did you understand anything of what you saw?

We arrived at night and suddenly I saw things I had never seen before. They had a network of air balloons, probably with camouflage nets, because of Buna [rubber production facility at Auschwitz III]. That was the first sight of Auschwitz. I also saw something geometrical on the way there. These were probably the camps, but I didn’t know.

"We arrived at night. We were hoisted onto huge trucks. We received six months of special care (Sonderbehandlung) which means we were transferred into the camp, even the sick and the dying, but we weren't aware of it at the time. We moved from Auschwitz to Birkenau. It was dead silent. All the blocks were locked, no one was allowed out and the camp looked like a ghost town. We were in shock. I looked for my parents because we arrived separately. We arrived in camp Bllb. It was the ‘Family Camp’."

[Taken from Y.B.’s Yad Vashem testimony.]

After a day, we were taken to the “sauna”1, and then, for the first time I entered Crematorium 4, that's the one with the gas chambers above. How did it happen? I was with the first group of children, we headed to the “sauna” next door, but along with some other children, I accidentally entered Crematorium 4, which was open, and we entered the gas chambers. There weren’t any people there and we thought that that's where we have to go. There were several SS men there who told us after a few moments: ‘No, no, no, get out and continue walking.’ Crematoriums I and II were the more modern ones, where the gas chambers were underground. Crematoriums III and IV were older, where the gas chambers were on ground level.

Supposedly, at that point, you hadn't yet understood the significance of that place.

No. But I looked, and I saw, and noticed there was only a small window, which I found out later was used to insert the gas. This was our first encounter with the camp, and we then we saw the entire big building. Then we walked back towards the “sauna” where our clothes were taken, we were shaved, scalded with different ointments and given disinfected rags to wear. Then, we were taken to the camp, were numbers were tattooed on our arms.

After that, we were in the “Family Camp” the whole time except once: in 1944, on New Year's Eve the whole camp went to the “sauna”. They turned it into a sort of a theater, where they put on a play for New Years day. We had to sit and listen for an hour, and then returned to our camp.

"After some time Fredy Hirsch arrived. He was sent to Auschwitz… He tried to gather the youth in one block and founded Block 31 for boys up to 16 years old. My group had about 40 boys in the block. It was a place we could stay in during the day, and return to our own blocks in the evening. […]

In the block we were divided into groups, and each group had an instructor. He would tell stories, teach us songs. He taught us like he would in a school. Sometimes we performed plays. In the early morning, Fredy would take us out to the snow half-naked to toughen us up."

[Taken from Y.B.’s Yad Vashem testimony.]

The transfer from the “Family Camp” to the Gypsy (Sinti and Roma) camp Birkenau:

"The August transport of 5,000 people was transferred separately on March 6th, to camp A (Isolation camp). Two days later, that transport was put in the Crematorium, and only our transport which arrived in December 1943, and also included about 5,000 people was left. Later, in May 1944, another transport of 7,500 people from Terezin arrived. We knew our transport has been getting "special treatment" for six months, and so we counted the months and weeks to our execution by gas. According to our calculation, we were supposed to enter the gas chamber on June 20th, 1944. June 20th came and went and nothing happened. Suddenly there were selections… lots of commotion in the camp, we thought they were going to disperse the camp. Everyone gathered their few belongings. Those selected were women fit for work, and men aged 16 to 45 […] that meant that I would have been killed since I was under age and with the group of boys that was supposed to be gassed. I was 14 and a half. […] on July 6th, a group of 80-90 boys was taken and transferred to camp E, the Gypsy Camp.”

[Taken from Y.B.’s Yad Vashem testimony.]

Can you tell us a little about being transferred out of the “Family Camp”?

For a certain time in Auschwitz, I worked with other boys in the "wagon commando" (Rollwagenkommando). We transported wood and other things from place to place. By virtue of this job I had access to different parts of the camp, and sometimes I also visited the crematorium. When we got the job, we were used instead of horses, so we could see the other camps. We could go up to Auschwitz I, visit the crematorium and to access places men weren't allowed in. We visited the Women's Camp and Mengele's Block. In my time, the B2E compound still existed. It was the Gypsy Lager. One block was Mengele's, and when we moved to the camp at first the boys weren’t sent to the “sauna”. The procedure was that if you moved from camp to camp you had to go through the “sauna”. In the Gypsy compound was Mengele and his twins' office, and there was a small “sauna” there, which meant a quick shower and out. We went through that “sauna” when we first arrived so we knew our way around the camp. Afterwards, we were there a lot and saw, or actually heard, how they were being killed. In the beginning of August, most of them were killed except for a few German Gypsies that were in the army. They were somehow in a more protected category. Even German soldiers who were found to be Gypsies were sent to Auschwitz, so there were a few who were moved to the Strafkommando (punishment commando), and then transferred somewhere else.

Were you afraid of the possibility of being exposed to what was being done in the rest of the camp?

Children at that age always want something new. It's as if you're discovering another secret. We were curious to know how people were burned. Is there an electric plate? How does it work? Like a curious child who wants to know what’s inside the toy. I had the curiosity of a future artist and wanted to know more than others. I asked the Sonderkommando (Special task force made up mainly of Jews forced to work in the gas chambers) whom I befriended, how it’s being done. They didn’t want to tell me at first, so I told them I might get out one day… and I didn’t believe it myself… but somehow I had a feeling I must ask.

Did you think about it? Didn’t you believe you’d get out?

It didn’t make any sense that anyone would get out. Even in the “Family Camp” we knew the exact day we were to be executed. There was rational thinking and at the same time the inability to accept it. We saw it every day, It was just a matter of time… Maybe, as a result of a large number of people in the camp they didn't have time to execute us, but the moment that they would have a break they would finish us off.

Do you think that your friends in the Sonderkommando told you what happened in the crematorium so that maybe you'll be able to tell others if you survive?

No. I was curious and asked so much, so why not tell me? I wanted to know about Edelstein, how he died, and about others. It was childish curiosity, but certain instincts were very active since one wrong move could mean death. You had to be very quick to make sure you wouldn’t get caught if you did something. My self-image from then is that of an old man and a child at the same time. We were next door to the Sonderkommando. Inside Birkenau there was a sub-camp in which there were three isolated barracks: one was the Strafkommando's, those who were there as a punishment, and the other two were the Sonderkommando's. No one was allowed to go into the Sonderkommando quarters. Whoever got in there stayed there and that meant death. But we, the children, were their neighbors and were not afraid of them, we even became friends. The members of the Sonderkommando gave us better cloths and food, they had everything. Three of them were good friends of mine: Israel and Katriel Zukerman, and Klemin Furman. 80810… that was his number.

After all these years you still remember his number?

I knew him so well. The fun part for the kids was remembering the numbers. You know, in those conditions kids are still kids with the humor and all that. So there, at the camp, I knew the Sonderkommando men and they knew me well. Once, one of them was at his position at an oven that was used to burn documents, and as he burned them, he noticed a portrait photo of me. He brought me the photo and said "Yehuda, by chance, out of thousands…." I saw that it was a photo that belonged to my uncle, Hirsch Bacon. I had given it to him and there was no other copy. So I knew that he had gone that night. It was a very close friendship.

I would like to return to the subject of art. Did you draw while you were in Birkenau?

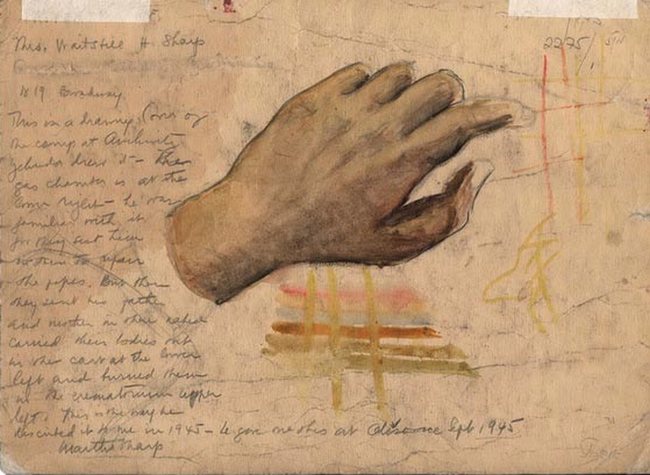

I drew mainly in Fredy Hirsch's barrack at the ”Family Camp”. I drew what we saw: the camp near us, how the dead were carried… I was very curious. The first time I looked, I noticed there were no holes in the showerheads. I walked there with the Sonderkommando. I got a guided tour and asked what each thing was for… and immediately after liberation in 1945, I reconstructed the gas chambers and the crematoria. I had an urge to remember it all exactly as it was. The drawings were used in the David Irving Trial. They perfectly matched the drawings they found at the SS's technical department.

As an artist, why did you decide to teach and not to dedicate yourself to creating art?

I have never been a practical person. And when I left Bezalel [Art School] I wandered how I'll make a living. At the time, there weren’t scholarships like today and I wanted to earn my living though painting. As a child I felt a sense of destiny; that I must tell what happened, about the suffering of Jewish children's' souls. And I thought that if I talk about it, people would become better. For me it was a package deal: I have to tell with the intention that people will be better and such a thing will never recur.

Were you disappointed by the reactions and the behaviour of people after the war?

Certainly. I had two reactions: silence and disappointment. Silence because people couldn’t bear the testimonies and disappointment because people didn't improve personally. It took me years to figure out even how to talk, that there are things that can’t be said or written. I saw that people were silent… Maybe I spoke too directly… I remember the first letter I wrote and sent to an uncle in Israel. I described exactly like a child, how tall the flames from the crematorium were, what the food rations were like… which uncle died, and so on… things a child thought would be important to say. That uncle suffered a breakdown, he was ill for two weeks. You can't talk like that. The technique of how to tell my story came much later. In general, the interest in us peaked only after the Eichmann trial, but by then I was already thinking in terms of educational value, and I saw that the horrors shouldn’t be told… It’s not good.

Is the Holocaust a motive that follows you throughout the years, both in your art and in your work?

From a psychological point of view, I was curious how the rest of the boys in our group reacted, and what happened to them – friends from Israel and abroad I kept in touch with. There were some who didn’t want to talk about it. There were three or four that got blackouts - it was erased from their memories. There were those that, due to the education at home, continued where their parents left of. There was one boy, for example, who, at a very young age, became a scientist and later on a professor in London. There were some who became intellectuals and the camp became something that was never spoken of any more. Most of them wanted to live their lives and forget, some of them consciously devoted their life to this cause, and one of them, Sinai Adler, one of the boys who were with me … his father was a rabbi. He said that he wants to serve God after the war no matter what, and eventually he became the Chief Rabbi of the city of Ashdod. He teaches and gives lectures to this day. There was another boy who was an SS Läufer (runner). One of his jobs was to walk around with a bucket, and as the transports arrived and the people were ordered to hand over all their gold and jewelry, the Läufer walked around with the bucket and collected it. Being an innocent child, he said that if he'll ever get out of Auschwitz he'll have more gold than the SS. I met him after many years and he became one of the biggest collectors of gold and porcelain. He is very rich. He wasn't aware that he fulfilled his childhood dream. When he told me the story he didn't make the connection. I said nothing of course, but it's obvious that a decision of some sort in childhood can change the course of life.

Where did your decision to become an artist stem from?

I knew I had something, a sort of an internal commitment to speak about what happened. But who would be interested in it? I had several great instructors who sent me to study art, and I spent the first years just painting non-stop. It was a blessing that I could express everything I had experienced in my own language - I painted and wrote diaries.

So your language is mainly painting?

Painting, but also writing. I wrote my memories down what I felt and thought in several languages, to this day. And that helped me, of course, get over this whole thing, this wall.

How do you perceive the drawings you created "straight from the gut" in 1945, today?

When I think about that period, I am interested in what I thought and how I expressed these thoughts. It was a period in which I wanted to develop in several directions; I wanted to be a painter, not a Holocaust-painter. I did my thing, and whether they wanted it or not, so be it.

I had to paint what I saw, what I experienced, and it helped.

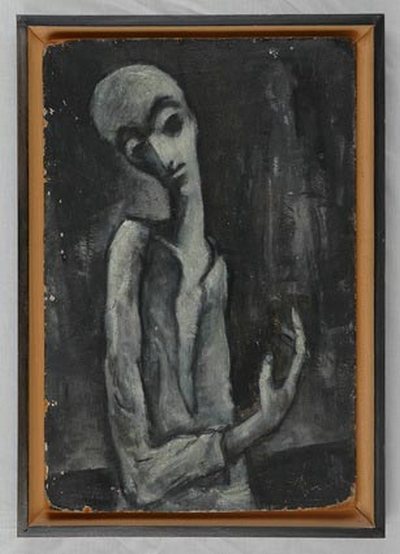

Would you be willing to comment on the two drawings in the Yad Vashem Historical Museum, one of them being the portrait of your father titled "In Memory of the Czech Transport "?

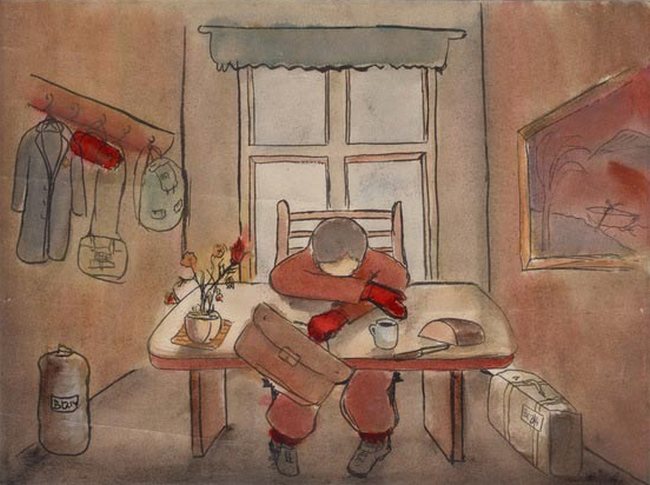

On the Yahrzeit (Anniversary of death) of father and mother I always did something commemorative like lighting a candle, for example. And there are also many drawings; one of them depicts the moment in that night and that hour I realized that my father was gone. It was a commemoration for my father. I drew this in 1945.

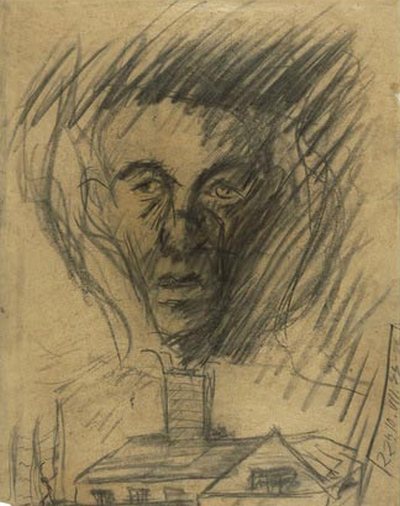

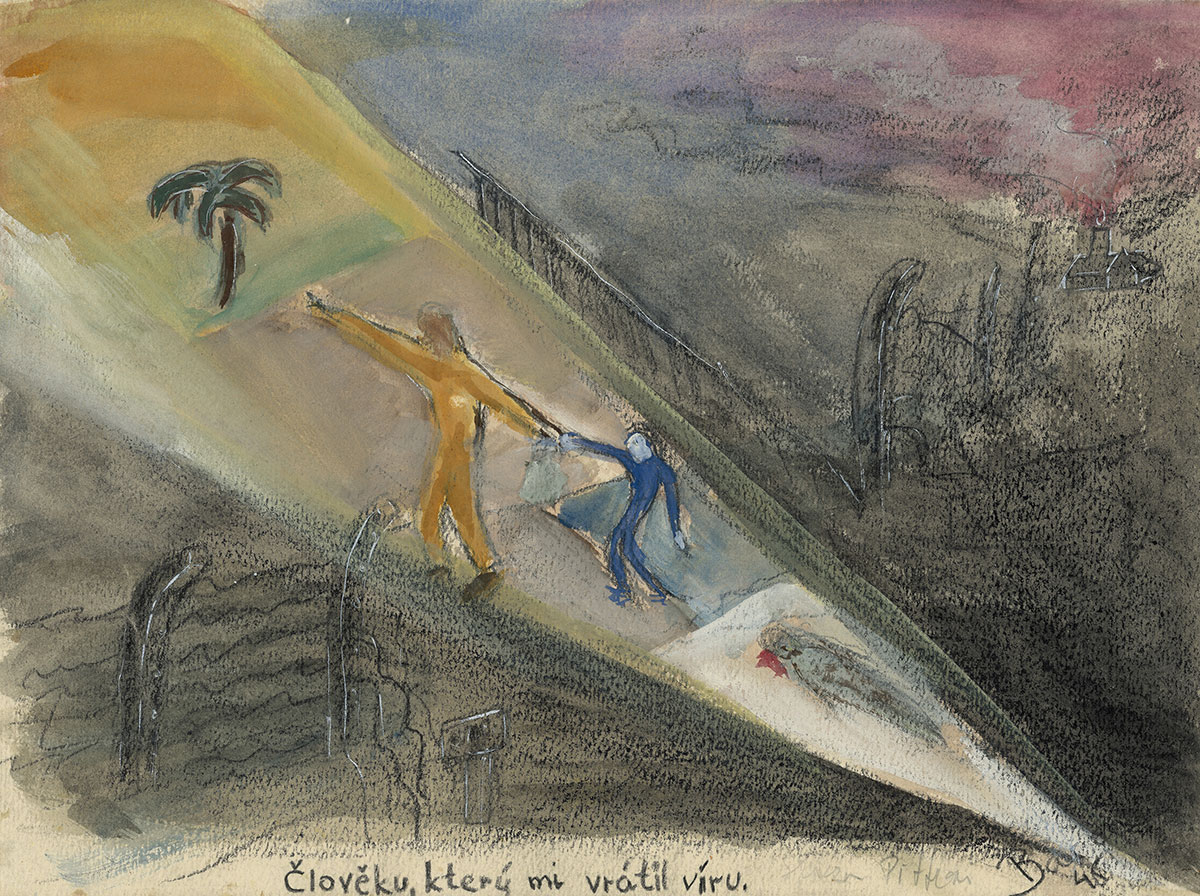

And the second drawing, titles "The Man Who Restored My Faith In Life"?

That was when I started studying painting and drawing in Prague with Avi Linovech [SP?] I told you about, and he gave me exercises in perspective. About the man, from an educational standpoint I see myself as being very lucky to have met him and others like him in Prague and later in Israel, mainly Hugo Bergmann, Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem and others who had a profound impact on me.

Wolfi – That same Rabbi Adler and I were the first children who arrived in Prague after the war. We escaped the other groups because when they went, after the war, it was impossible to travel directly to Prague. Everything was in ruins, the bridges, too. Somehow, we got there by morning and didn’t know where to go. Wolfi was from Prague so we decided to go to the Jewish Community. In the community, there were several people, the survivors from Terezin, and they told us that they didn’t have means to take us in, "but there is a person here who'll take care of you," and that was Premysl Pitter. Pitter was a wonderful person, who established, with help from friends, places for the children that arrived after the war. He got a permit from the welfare department of the Ministry of Education to confiscate German palaces and turn them into convalescent homes for boys, and we got into one. It was a big story, because he also saved Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) boys. After the war, the Czechs took all the Germans and deported them to the Sudetenland (northern, southwest, and western areas of Czechoslovakia claimed by Germany) to live in camps in very bad conditions. Pitter, being appointed by the Department of Welfare, could go to these camps, take the worst cases and put them in convalescent homes next to us. Immediately after the war, the hatred toward Germans was so great, that anyone speaking German was risking his life. And suddenly, there was this oasis of tranquility, of Jewish boys mainly, but there were several children from Lidice (village wiped out in retribution for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich), and some five and six year old children found in Auschwitz who no one knew who they were, and there were some German children. In short, Pitter was like Rabbi Leo Baeck, both were the only ones who immediately took care of children with no regard to their race, religion or gender. They supplied clothes and food, and it was crazy back then. They were so humane, today it’s taken for granted, but at the time…

Yehuda Bacon (b.1929), To the Man who Restored my Belief in Humanity Prague, 1945

Pitter was a wonderful person and I think he saved us from the horror of the past. It was the first time we trusted someone. We didn’t trust anyone, why would anyone be kind to us? Everybody wants to hit and kill us. And he wasn't some missionary or propagandist who tried to persuade us to do one thing or another. His and his friends' kindness is what changed us. All the children who still live today remember him: both Jews and Germans can't forget him. Let me tell you a little story that demonstrates how magnanimous he was: Sinai Adler was sitting in the dining room, eating with the other children, wearing a hat. Pitter came and thought Sinai just didn’t know table manners – that you eat without your hat - and took the hat off his head. Hans Adler, known now as H.G Adler who wrote the books about Terezin, told him that it's not a lack of manners, but that Sinai was a Rabbi's sun and that according to tradition it's customary to keep your head covered. So Pitter immediately returned the hat and apologized. Fourty five years later we invited Pitter. He received a Righteous among the Nations medal from Yad Vashem. Sinai Adler was there, too, for the reception and Pitter asked him "Can you forgive me?" After 40 years! I corresponded with him for 40 years.

So I painted a picture: Pitter bringing me from death to earth, from darkness to light.

After what we've been through we had no faith in humanity. We had a feeling that although we were young we knew more and were wiser than the adults. That man saved us psychologically, the fact the hatred was turned to humanity is among other things, thanks to him. And thanks to Buber. Later they met each other and became friends.

How did people like Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem influence you?

I was fortunate to have a chance to listen to them. I Simply, trusted people like Pitter and Bergmann and Buber. We were children, and children have the ability to sense who speaks to them and who speaks at them. The welcome in Israel was horrible, there were instructors representing rightist and leftists, religious and secular and we had to decide where we want to go, to this kibbutz or another. I was asked, and I told them I didn’t care. They had promised that I would get the chance to study and that's why I came. I wasn't interested in politics, I didn’t believe anyone. I was 16. I said I only wanted to study. What was their answer? That I was wrong, that it's different in Israel. That was the first shock; they were out to get souls. Luckily, I had letters of recommendation from the artist I studied with.

When did you get the opportunity to meet the people you mentioned?

Through Hugo Bergmann who gave me a recommendation. Bergmann was one of the greatest educators, not just mine, but of others as well. I saw true modesty in the way he spoke with students. If in philosophy class he was asked something he didn’t know, he would reply: I don't know, I have to check in the books, maybe I'll give you an answer next week. What academy chancellor would say these days, "I don’t know?" When I was aboard, I sent him postcards, greetings, and he would answer each one by hand. He was a wonderful person. He took everyone seriously, both student and cleaner; each one was a unique individual for him. I learned from them not only through what they wrote but also through how they lived. Bergmann was a Zionist at the age of 19 and lived by that. He respected everyone. Martin Buber, for example, if a student asked him something in mid-class he could spend 20 minutes answering him. This dialogue was the most important experience in my life. These were people you could trust, their words and actions were equal. They exemplified it in their daily life.

I wanted to make a living from my art. I was interested in the treatment of human beings because I learned how important that is. How one word can make or break a man. After the war, I was so sensitive that I could cry if someone said a good word or was kind to me, or the other way around. I tried not only to study painting but to be a human being, and I had teachers who were living examples. It's also the basis of Buber's philosophy – the dialogue. It doesn’t always succeed, but sometimes it works.

Do you think this dialogue later enabled you to understand how to express the things you wanted to say?

Of course, in teaching and education what you try to achieve is very important. At first, one thinks "I want to express my experience", but later if it’s individual it's not that important. What can you learn from the Holocaust today? Historians do their job, that's important. Sometime I laugh, but it’s their job, they need to do it. I think there are a lot of messages and everyone learns his message according to the depth of his thought. And I didn't want to emphasize the hatred. I think the abyss exists within everyone, maybe not Einstein and Schweitzer, maybe they would not have turned into animals under any circumstance. But most people carry that potential danger, and I hoped that the root of our souls, that something else, is what makes human beings. Since there were educated people who turned into animals and there were simple folks who didn’t cave in. I wanted to show that point of view as much as I could. Both in art and, as much as possible, in life, encounters, conversations with people, to influence that direction, that's important to me. Everything else can be read in books.

You mean humanitarianism?

It's more than that, the real thing that maybe begins with humanitarianism.

That brings to mind Primo Levi's insights – you say there is an abyss in everyone – and it seems that after the war he had continued to live in that abyss. Levi's experiences led to a different outlook on life.

I was asked after the Eichmann Trial whether it had any value, to suffer so much. I said it could, if it affects a person so profoundly, it means that suffering could bring something positive If this turmoil can bring him to the realization that the other is similar to him in some metaphysical level. But it's very difficult and I don’t wish upon anyone to learn it this way. It means that suffering can cleanse or cause people to see other perspectives. I say that great art only opens another perspective into the same thing. I believe in "revelation", something that a person sees that shakes him: for example, a music lover who can be overwhelmed to tears, and it opens a window for him. What does a great painter do? Ah, another apple? Of course it’s the same apple but whether it's Cezanne's or Van-Gogh's, it’s a new perspective of that same apple, or that revelation. If I ask, what can be said about love? A loved B loves C and so on. And then came Tolstoy and wrote Anna Karenina and created something new. A great artist can find within A, B or C something new. That's the artist’s mission, to reveal a new perspective. And if we take this further, each person can reveal a new perspective for us, but it's very hard to get it.

Do you think a person who hasn't experienced the Holocaust has the right to express the subject in painting, for example?

Everyone has a legitimate right to give a new view, a new perspective – in this case about the Holocaust. Anyone who can enrich me.

There is always a risk of slipping into kitsch with this subject.

Some people learn through kitsch. At first they are excited by the kitsch, and when they look deeper into it they discover it’s more nuanced. When I didn’t know anything about music, the simplest rhythm excited me. Some people think Rock and roll is the best music, but if you study further you might think that Beethoven or Bach are a little better or nuanced and can open another window… but every age and each stage has its own way. I believe it's some sort of integration, that every art tells the same thing, just in its own language.

Do you think the gap between the survivors and the next generation can be bridged? That it's legitimate for the second and third generation to teach the subject?

Yes, yes, each with its own ability, not just artists. The very fact that a person regards another from within is effective. Every true thing has an effect. True in the highest sense, because it breaks something, it breaks the insignificance; the insignificant is the poison of the soul. You experience something again and again, but suddenly there is something, suddenly you see something and every language can convey it. I don’t remember which philosopher said: every artist has experienced perfection at some point. Call it God, I don’t know… He who has experienced perfection in human relations, in a great love… In something. And his whole life he then tries to capture that perfection or divinity, but he knows it’s impossible, he can’t grasp it and put it in his pocket. It's too big! The little leaf that is us can't be the tree, but he knows there is something whole, that is a tree and tries to express it. Any sincere work, like a prayer, gives us some part of that completeness. Artists might be more talented, but I believe that anyone has a gift for it. Whether you meet someone who is really exceptional or an ordinary person, that which affects us all is that we are all part of that great perfect completeness - this great divinity.

So even after such a horrible crisis in our history and your personal history, you hold on to faith?

Certainly. Look, we are not so good fundamentally but we can relate to goodness. Goodness is God for example, he is absolute, we can relate to Him, but we are not good.

I asked how it's possible to have faith after the Holocaust. And I have faith, but that's already a question of what "faith" really is. And I do believe there is such a thing. We don’t have it, but we can relate to it and it can have an impact and give us hope and the answer that life does have meaning, but sometimes we don’t understand it.

- 1. The "Sauna" was the first stage of the de-humanization period, where newcomers began the registration process. They were stripped of their clothes and made to feel like a number instead of a human being. They were showered, disinfected, shaved, tattooed, and given a prisoner uniform and wooden clogs.