The deportation to camps was the beginning of the tragic fracturing of the individual. Family members were torn from each other during the selektions, and for the most part, surviving members were left all alone. Prisoners in the camps were forced to deal with hunger and with disease, with forced labor and with torture – both of the body and of the soul. In this interview we wish to present an alternative story of the camps – a story that shows the human element and reveals the brotherhood that was able to persevere despite the evil that lurked in every corner. It was not a trivial matter for one prisoner to lend a helping hand to another, or to provide another prisoner with a warm and sheltering space. In the reality of life in concentration and extermination camps, it was almost impossible for prisoners to think of anyone but themselves. However, when concern for others and mutual responsibility was expressed, these became anchors of compassion, a way to maintain one's sanity and even, sometimes, a chance at rescue.

The story of the rescue of Yitzhak Livnat, who was a boy of 14, and his extraordinary connection with Chaim Raphael in the death camp of Birkenau, brings to light the significance of human solidarity and the spiritual elevation that was still possible even in the face of the surrounding atrocities. We are pleased to present an interview with Yitzhak Livnat ("Itzik"), who was born in 1930 in Seylesh, Czechoslovakia (and whose original name was Sandor Weisz, before he moved to Israel and changed it), and with Chaim Raphael, who was born in Salonika (now called Thessaloniki), Greece six years earlier. Interspersed throughout the interview are segments from two memoirs that explain details of each of their stories.

Chaim, please tell us about your life before the war: your family, your childhood, your memories of the community.

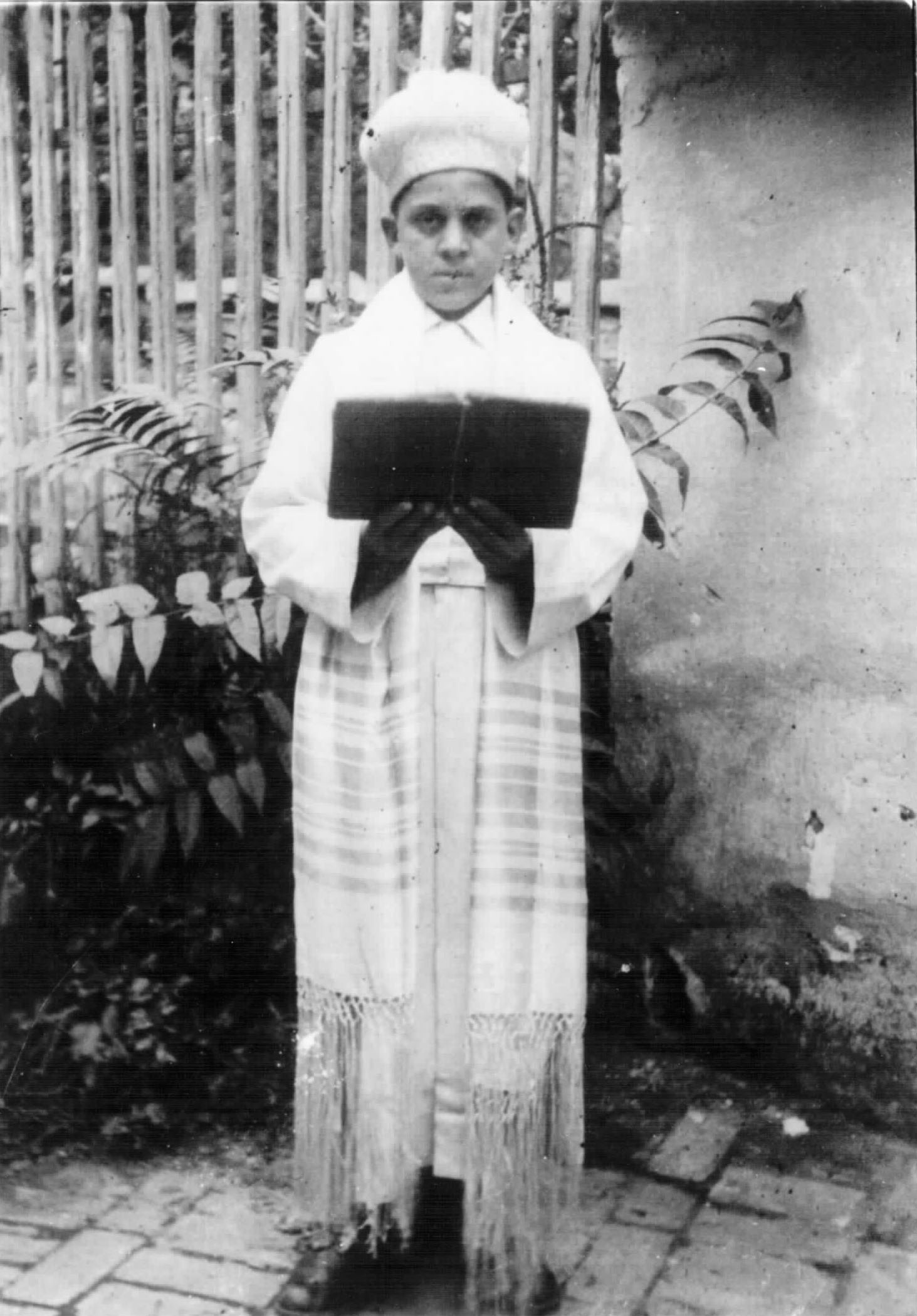

Chaim: I was born in Greece, in Salonika, to my parents Sultana and Zadik Raphael, in 1924. My house was a traditionally religious house. I had two brothers and two sisters. There was a lot of poverty in my city, but my parents inculcated in us the feeling that we should be proud to be Jewish. My father would say in Spanish, "Not everyone in this world has the privilege of being a Jew…." I was very, very connected to religion; at my Bar Mitzvah I read the Torah Portion of "Vayikra" (Leviticus 1:1, -Ed.). I loved Judaism, the Torah, the traditions and the holidays. On Sabbath you could go wherever you wanted, completely freely; you could go to synagogue, you could also go to a restaurant to eat something….

And yet my mother worried about educating her children to do good deeds and "mitzvoth". She invested all her resources in her children and almost didn't worry about herself.1 My house in Salonika was a house of melodies. My mother sang as she worked in the house. My sister, Rivka, loved to hum the melodies of the Greek operettas and Ladino songs. Music was part of our lives. I always dreamed of obtaining a formal education in music… At the beginning I took lessons on a grand piano, that was located in the house of one of our non-Jewish friends, and later I learned to play the accordion.2

What did your parents do for a living?

Chaim: We had a huge coal store… In Greece it was very cold and this way we had everything we needed.

In that period I had to work in my father's store and to replace my brother Shmuel who, at the time, had enlisted in the standing Greek army. My father had a store that sold coal at 68 Waslisi Olgas St., in the Analipsi neighborhood. Most of the rich Jews of Thessaloniki lived in this neighborhood… We also lived there… We were not considered a rich family, but we were a family of some means.3

Did you go to a Jewish school? Can you describe your treatment by your neighbors?

Chaim: I learned in a Jewish school. In Greece there was always more hate than in other places. They were angry at me that I killed Jesus, but I had never met Jesus! I didn't know who he was… After the Germans occupied [Greece], in April 1941, automatically the Greeks became brutal. Every day there was an article written against the Jews. Some of the writers were forced to write against the Jews. And because of this, when you speak about someone without knowing him, and every day something else is happening, you hate this person without knowing him. The friends that I had grown up with suddenly hated us.

Can you describe your life under the Nazi occupation in the city?

Chaim: There was a feeling that something awful was going on in Europe – exactly what, we didn't know. As I said, on April 6, 1941 the Germans invaded Greece; the feeling was horrible. On the day that the Germans invaded, I felt that it was a black day, as though I knew that something terrible was about to happen. One Shabbat, in July 1942, they concentrated all the men, from the age of 18 to 454. I doubt I was even 18 then. We didn't know what awaited us… The people were weak and hungry. One young boy fell down near us. I took him, along with someone else who was there then, and we brought him into the shade. I didn't do anything bad, but this act really cost me. We returned to our places, but I lost my position in the line in which I was standing. From among the lines, a German officer emerged […] and put me in the middle. At the beginning I had to do sort of athletic exercises. Afterwards I began to get hit; they spilled water on me, I was kicked with the Germans' boots. I got to the point where I didn't feel anything. I was tossed aside; I didn't have the strength to get up, to walk. They tore my clothing, they made a rag out of me. For at least a month afterwards I stayed at home - I couldn't move.

Itzik, can you tell us about the house you came from and about your community?

Itzik: I was born in a small town that was home to many cultures, many different languages. It was a microcosm, a strange mixture – Hungarians, Ruthenians, Germans, Sinti and Roma (known colloquially as gypsies, -Ed.) and Jews, and each of these used a different alphabet: the Latin alphabet that the Hungarians used; the Cyrillic alphabet that the Ruthenians used; the Germans used Germanic and Gothic letters; and the Jews were Yiddish- and Hebrew-speakers and used the Hebrew alphabet. It was a tiny, effervescent microcosm. I had a wonderful childhood.

My town had different names and all of them mean the same thing: the name most commonly used even today is Nagyszolos, despite the fact that today it is in the Ukraine. In Ruthenian the town was called Vinogradov, and in Ukrainian, Vynohradiv. The Jews called the town Seylesh in Yiddish. It was a town with 15,000 inhabitants in 1944, the year of its occupation and collapse, and one-third of them were Jewish. And the Jews were divided into two factions – one was Zionist, modern and spoke Hungarian, with a Hebrew elementary school. For instance, in first grade I learned mathematics in Hebrew. That was one side of the Judaism in my town. On the other side, the Orthodox, among them the Hasidim, hated Zionism and fought against it. But this war, in my town, was reigned in. In the broader area there was a real struggle between these two factions.

How many siblings did you have?

Itzik: We were five children; I was the fourth. After me was my younger sister, Icuka. My two older sisters, my father, my younger sister and I were all deported to Auschwitz. My older brother was in a work battalion in the Hungarian army. We lost my mother in 1944 to an illness. She passed away at home and was buried in the cemetery of our town when I was 14.

What are your memories from the first days of the Nazi occupation of your town – what changed?

Itzik: I was born on a huge farm belonging to a Hungarian nobleman, whose size was measured in square kilometers. Hungary was the last feudal state in Europe and I was born at the end of the age of feudalism. My father was very loyal; loyalty for him was of the utmost importance. He was Hungarian with every fiber of his being: he always took pride in the fact that he had served (Emperor) Franz Joseph5, but he called him "Franz Yoshke", as though he was calling him by a nickname, like a friend. And he was convinced that "nothing would happen to us. There couldn't be anything like that." His belief was that nothing like that [what was happening in Europe] could happen in Hungary. All the rumors that reached us, and all kinds of strange rumors did reach us… They talked about this at home, but they said, "Don't pay attention to this, it goes against all logic…." And we were proud Jews! Proud Jews – meaning that we didn't hide and we didn't call ourselves "of the Mosaic persuasion" – that was a device that was born not long ago. We were Jews, without a doubt.

Can you tell us about your arrival at the camp?

Itzik: We got to Birkenau and they performed the selektion. I wanted to go with my little sister. And then someone said to me: "Hey! Don't go there – go there." What's this? Could I leave my sister?? No! And then a neighbor of ours, Mrs. Rosenberg, who had arrived in the same cattlecar as we had, said, "Icuka come with me." And so I went together with my father, wherever they sent me. If I had insisted on going with my sister, of course they would have let me.6

After two or three days, when all of those dreadful rumors, that… (the Jews had been gassed to death –Ed.) Although nothing like that was possible, I understood that I had lost Icuka. I really loved her. She was the youngest, she looked up to me. They sent my father to a different camp the next day, from Birkenau to Auschwitz, to work, and they put me into what was called the Kinderblock (the children's barrack). When I understood what was happening around me and I thought about it and internalized it, I went out at night, I looked up at the heavens, I cried and I shouted, "Where are You? How can You let something like this happen? And if it's true that the smoke is really…then – I curse You!" I came out against Him as strongly as possible. "Here, send a lightning bolt and kill me!" It was the beginning of my loss of faith. Since then and until today I haven't experienced anything to strengthen my faith again. Nothing. I was strengthened by people all along the way, here and there, and because of that strengthening (hugging Haim)… we lived to see this day.

Chaim, Do you remember the journey to the camp?

Chaim: It was a tragedy. I don't know if there is a person who can describe the suffering of eight days spent in a cattlecar. I don't know if there is a movie director who could recreate the atmosphere in those sealed cars during seven days and eight nights. They put eighty people into a cattlecar, and sometimes more. It was absolutely horrific. The suffering, the embarrassment, the humiliation. My sister had to relieve herself among seventy-five other people… It's impossible to describe.

But me, I sometimes turned this tragedy into a joke. In the cattlecar with us there was a doctor who was very afraid of catching lice – we were there for days without washing, without even seeing water, without anything. And the doctor would sit by himself and I asked him every time, "Doctor, how many days is it possible to live without food, how long can a man hold on?" He would answer, "It's possible to hold on for 40 days." Every morning I would remind him: "Doctor… how many days?" And he would answer: "Forty days." On the seventh day I asked him: "Doctor?" And the doctor was dead. "Doctor", I said to him, "You've gone? Why so soon? You said we could hold on for 40 days…" Days and days without food. I don't know how it was possible…

What happened when you got to the camp?

Chaim: We got to Auschwitz at night. They greeted us with beatings, with shouting, with dogs. Immediately they separated women from men, by hitting us very brutally, and my whole family disappeared.

I loved playing music more than anything; that's why I took my accordion with me. I got hit because of it and they took it away from me. I cried, just like I had cried when they took my sisters, because I thought a person who can't play music can't possibly be happy in this world.

Can you describe the meeting between you at the camp?

Itzik: I was in Birkenau in the Kinderblock, the children's barracks. And I was lucky because there was one Kapo (A kapo was the overseer of a work brigade, called a "kommando" –Ed.), a Polish Jew, who was actually illiterate, named Tadek Dzeidjic, who liked me. He was responsible for the disinfection group (the work group that was responsible for disinfecting the cattlecars was called the Desinfektion-Kommando) and I shined his shoes so well; I also read him notes in Polish, and he laughed out loud that I didn't know how to pronounce Polish words. He made such a joke out of me. And really, I didn't know how to read Polish.

The job of the kommando was to receive the cattlecars that arrived in the camp after a journey of seven days or of two days, and to take out of the cars all the property and things that people had brought with them. They didn't allow anyone to just take anything out of the cattlecars; they were filled with all kinds of secretions7, and also with corpses of people who had died on the way. And this kommando had to immediately evacuate everything that was in the cattlecars, to transfer the belongings to another kommando called "Kanada"8, and to immediately begin disinfection: to clean, wash and disinfect the cattlecars so that the train could leave the ramp and another train could pull in.

This job gave the kommando a great advantage, because it was possible to open up the 200-300 liter barrel of disinfectant liquid they used in order to spray the cattlecars, and to throw inside tins of canned food that were found inside the cars, mostly sardines and whole bottles of vodka, or things like that. Too bad we couldn't have thrown inside smoked meats. And they would come back to the camp with this merchandise, and this merchandise was, in the nature of things in the camp, worth a few times its weight in gold.

The evening before Yom Kippur (the holiest Jewish holiday of the year – Ed.), "Mister" Mengele performed a selektion - two barracks of children were there. And I didn't pass this selektion because I wasn't tall enough. There was a wooden board fixed in place with a nail and everyone had to pass under it, and whoever was shorter didn't pass. And I didn't pass.

They crowded us into a barrack; there were about 700 children there, in awful crowding - everyone was touching everyone else. And I was shoved in. I made my way between the other kids in order to get to the front of the barracks, there I saw who was entering and who was leaving. And when evening came and the sun went down, the children decided to pray "Kol Nidrei" (the prayer traditionally recited on the evening of Yom Kippur – Ed.). Two boys my age, from my town, and I emphasize their names – so that some memory of them may remain – Leibovich Shani (Sandor) and Chaim Teitelbaum, said to me, "Come join the prayer." And I didn't join the prayer. And they tell me that story of the Baal Shem (the founder of Hasidism – Ed.) that the heavens won't open because of me… And I didn't pray… Suddenly the door of the barracks opens and one of the men of my kommando, who knew me, entered. I said to him, "Janek, I'm here." Janek was a Polish Jew. The whole kommando was Jewish. He had the ability to walk around the camp unrestricted. We, those who were slotted for… [extermination], we were locked in. He came to visit a friend of his, the Blockälteste (a veteran prisoner of the barracks, who usually had an administrative function – Ed.) and said to me: "I saw you." And then he went in, and spent an hour eating and drinking in the closed room. But this actually doesn't express how much time I felt had passed - I felt as though sixty years had passed. When he came out I said to him again, "Janek", and he made this gesture like "I saw you", and left.

An hour later, just as Suti (Yitzhak Livnat) convinced himself that all hope was gone, Janek returned with another man. Dzeidjic's assistant never even glanced at Suti as he went directly to the Blockältester's room once again and closed the door. After a short time, the visitors opened the door and came back out. Janek walked directly toward Suti, pointed to him, and yelled in an angry tone, "You are coming with us, now!"

The room fell silent and everyone seemed to hold their breath in shock as Suti was grabbed and taken out of the barracks.

The men took Suti directly to an empty barracks where Dzeidjic was standing in the middle of his small working group. Everyone around him was sitting. Suti looked at Dzeidjic, hardly able to speak. Dzeidjic gave him a steely look, put his finger to his lips as a signal to be quiet and pointed to the upper bunk at the farthest end of the barracks.10

Do you remember what you were thinking as you walked from the kinderblock to the block of those who were sentenced to death? What did you think, how did you feel? Did you speak on the way?

Itzik: I was in shock. I was trembling like a leaf. I wasn't capable of thinking about anything.

Suti could barely find the strength to pull himself up the stairs – his legs had been drained of all energy – but he somehow scrambled to safety. There, to his surprise, was a Greek Jew who comforted him by putting his arms around him until he stopped shaking. He began talking to Suti, first by telling the boy his name – Chaim Raphael – then telling him stories in a soothing, comforting tone.

He sensed by the trembling of the young boy that he had just survived a devastating experience, the seriousness of which the Greek man could only guess at by the length of time it took to calm him. To take Suti's mind off the trauma, Chaim Raphael quietly sang Italian folk songs and encouraged him to sing along. After more than an hour of quiet singing, the boy finally stopped trembling. Suti later learned the price Dzeidjic had to pay to extricate him from the death barracks: five cans of sardines and twenty U.S. dollars. Such was the appraisal of a single human life at Auschwitz-Birkenau in the autumn of 1944.

Before dawn, the other children and teenagers were exterminated. All except one.11

And the communication with Chaim… I think the fact that he is a Jew and I am a Jew, we introduced ourselves that way because we said "Shma Yisrael" (a central Jewish prayer. The core of the prayer is the affirmation of Judaism and declaration of faith in one God. It is traditionally said before death – Ed.) or something similar. He saw that I was in shock, trembling like a leaf. And he, what he does now he did to me then: he responded to me by singing, almost immediately, he began to sing and he taught me to sing.

On January 18, 1945, Yitzhak Livnat was forced to march on the death march from Birkenau to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

Itzik: My father and I got to Mauthausen in two separate transports. Neither of us knew what had happened to the other. And on the first day that I got there he was already there. The prisoners of the block had to arrange themselves in rows of fives so that the SS could count them quickly and they yelled, "Send five more" (so that the full quota for the count would be met) and then five more came in and among them I recognized my father. And he recognized me and I… He saw me, stopped, and froze. And then the SS came in. My father stretched out his hand to me - this is something that was absolutely forbidden – and said, "Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich habe meinen Sohn gefunden" ("My son, my son, I found my son.") And the SS said to me, "So go hug him…"! We became the miracle of the camp.

Afterwards we went through the second death march together to our last camp, Gunskirchen in Austria, a camp that opened its gates on March 12, 1945 (my fifteenth birthday). We got there two weeks later, completely plagued by lice and sick with typhus, both my father and me. We were liberated by the men of an American division. We left there, the two of us, on the verge of death and met an uncle of mine, my cousin's father. We told him, "Let's go together", and he said, "You go first and I'll catch up." Two weeks later, I was the only one of this threesome still alive. [Both my father and my uncle] died a short time after the liberation.

In the fall of 1944 Chaim Raphael was transferred from Birkenau to a work camp near Breslau, and in January, 1945 he was sent on a death march to the camps of Flossenburg and Ohrdruf. Chaim tried to escape but was caught and transferred to Buchenwald and from there to Theresienstadt, where he was ultimately liberated. In Theresienstadt Chaim was introduced to Esther, a woman from Corfu. She became his wife. Together they went back to Salonika, where they were married, and in June, 1946 they made aliya (immigrated) to the Land of Israel on an illegal immigrant ship called the "Haviva Reik".

The war ended. How did you keep on going?

Chaim: I returned to Greece. The situation was really awful. In Greece you went to the army at age 21. I was then 20-21, I didn't know exactly. And then I heard someone say that it was possible to get to Palestine. I was one of the first to sign up and I said, "After seeing what happened with these people here, I don't want to be here." I got to Palestine after a lot of trials and tribulations – back then there were no airplanes and I spent entire days in a cattlecar until we arrived. I came to Israel without a family, without a profession, without knowing the language, without anything - with nothing. I worked in a textile factory where we were paid one lira and fifty groshen per day; it wasn't enough to buy anything with.

I sat and looked at the doors. And the owner said, "What are you looking at?" And I answered, "I don't know how I'm going to escape from you, because from you I get nothing." And he said to me, "You'll see, you'll be big, you'll learn." And I said, "I want to do that now. If not now… " And I just got up and left. I did all kinds of work, and then slowly, slowly, slowly…

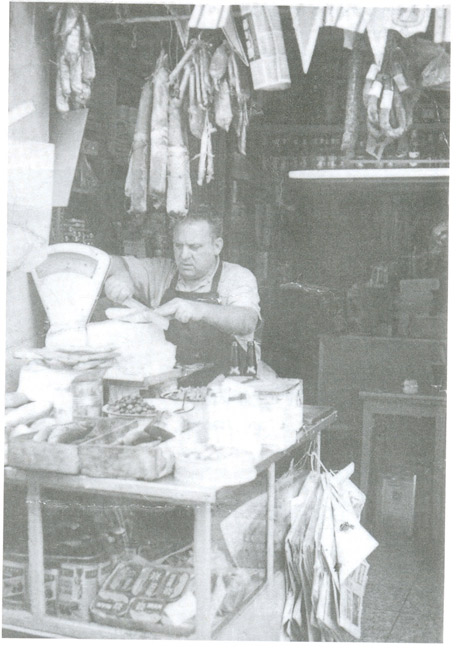

The store opened in 1958… I was then in my thirties… We had a lot of energy, and lots of ambition. We worked long hours, from morning until night… slowly the store took off. I expanded the number of products and mostly started working with restaurants.12

Itzik: The only thing that was in my head was to go home! They put me into some room where the American army gathered all the sick. I was there for a number of days, unconscious. In the meantime, my father died. I woke up to find the doctor saying to someone who was standing there, "We need to send this kid to a sanitorium in Switzerland." And I, remembering my geography lessons and knowing where I was and where Switzerland was, I knew where my house was. I escaped from the hospital and went back to ask about my father. And then they told me, "Do you see that pit? That's where they threw him, they covered him with lime." And I went home. And I reached home! It took me a while, a number of days, to understand where's north and where I am. My uncle, who had returned before me, heard my story and then said to me, "From today on you'll be my son!" On the spot, by order, he adopted me. He sat me down on his wagon and said to the horse, "Home!" and the horse knew the way back very well. My uncle fell asleep in his seat. While he was sleeping I got out of the wagon and left the city… That was my farewell. And I went to Palestine.

I went on my way, I got to Budapest; from there I escaped with a group that crossed the border, the occupation zones: from the Russian zone to the British zone. I was put into an orphanage in an Italian city, Selvino. In Selvino they tried to teach us and to create the atmosphere of the land of Israel. I really loved it, but I wasn't making any progress in getting to Palestine from there. So I escaped and enlisted with the forces that helped with aliyah. I worked loading ships. They promised us that we'd make aliyah on a certain ship, but the ship sailed [without us]. We went on strike. Afterwards a second ship came, and again we worked loading the ship, and again the ship sailed [without us]. This time it was really too much. An hour later a tiny little boat appeared and they told us, "Get on." We set sail in a terrible storm, and it turned out that the two ships were in touch with us all the time: the big ship ("Shabtai Luzinsky") and the little ship ("Shoshanna"). We actually traveled together.13

The British caught us14 when we were already on the bus that took us with those who came to receive us. All the people who worked in the dairies in the area, and all the members of the kibbutz came – they got an order to burn all their ID cards so that we could all say we were named Abraham son of Abraham and that we were all from the Land of Israel. The British didn't like this. They collected all of us and put us all on a deportation boat to Cyprus. We got to Cyprus and that's where they started teaching us how to play the game and pretend we were from Israel. When the Palestine Police got to Cyprus, they tested us one by one and asked us all kinds of questions. The last question was when the policeman took 50 mil out of his pocket. No one called it 50 mil, they called it a "shilling." He threw it up into the air and caught it and asked, "What do I have in my hand?" "A shilling," I said. I passed.

After he made aliyah, Yitzhak Livnat lived at Kibbutz Merchavia for about six months. In 1954 he married Ilana Barka'i, who had been born in Israel.

Itzik: I built myself a new identity. I took the name "Itzik" even though my name wasn't Itzik. My name was supposed to be Yishayahu. I didn't like Yishayahu. But the Hungarians had insulted the Jews by calling us "Dirty Itzik" and "Itzik the Little Jewboy", so I took the name Itzik. And for forty years I didn't open my mouth. I never spoke my native language. My identity was a question mark even in my own eyes. And Ilana decided to marry me.

Can you describe the moment you met Chaim again in Israel?

Itzik: It was 1967, after the incredible victory in the [Six Day] war. The company of which I was one of the managers and owners [the company still exists and is called "Ta'avura"], was sent to collect things from the battlefields: we collected damaged enemy tanks - Egyptian and Syrian - from the Sinai and the Golan Heights, and we were to bring them to the center of the country. We were almost the only company that was capable of doing this work because we were involved in special, heavy hauling projects. We had an extraordinary staff of workers. We sent them to all kinds of places, battlefields, where they loaded the tanks and brought them back. The drivers would leave every Sunday and return with tanks they had managed to extract after a week. We needed to supply the drivers with food for a week. That particular day was a Friday afternoon; we had to find food because the drivers were leaving on Saturday night for the north and the south. Ilana and I found a delicatessen and inside we met this man who was not very pleasant. Stubborn and uncompromising, not a believer… Ilana said to me, "Let's get out of here," and we left.

Did you recognize him?

Itzik: No, I didn't recognize him. In the end I said to Ilana, "Let's go back to him". Something had already started…

We went back, we filled up some cartons. He didn't like to sell. "…What's this, you want to empty my whole store?" The carton was ready on the counter and I took out a checkbook. He takes the carton back and says, "I don't accept checks." It was Friday afternoon (In Israel, banks close on Friday afternoon for the Sabbath until Sunday morning –Ed.), and they still hadn't invented ATMs. I say to Ilana, "Ilana, go to Acropolis" – that was the restaurant next to our office, a restaurant we ate in all the time. "Ask Moshiko to give you some cash."

And Chaim asks, "You know Moshiko?"

I say, "Yes."

"Does he know you?"

I answer, "I guess so."

He phones Moshiko and says, "There's a guy here who says he knows you," and gives me the telephone.

I tell him, "Moshiko, hello, I'm in South Tel Aviv and I need some cash."

Moshiko says, "What, you're at Chaim's?"

And I asked, "Your name is Chaim?"

"Yes."

Then Moshiko says, "Give him to me."

I give the receiver to Chaim, he says something, and at the end Chaim says to me, "Take the carton, take what you want, the whole store is yours!"

I tried to give him a check again, and again he says, "We don't take checks."

I told him that I would come back on Sunday to pay him and he said, "You do whatever you want."

And then I say to him, "You were in Auschwitz?"

He answers, "Ah! You see the number!"

I tell him, "Do you remember that you taught a boy to sing?"

He says, "I sing all the time, I still sing. All the time I sing." (It's a fact that he had a whole choir of singers from Greece).

And I say, "I am the boy… " It's clear that all the defense mechanisms and walls and fences he had around him collapsed completely. We hugged and we kissed and the whole store was involved with our story. And since then, every family occasion, either mine or his, we are always there for each other.

What would you like to say in conclusion?

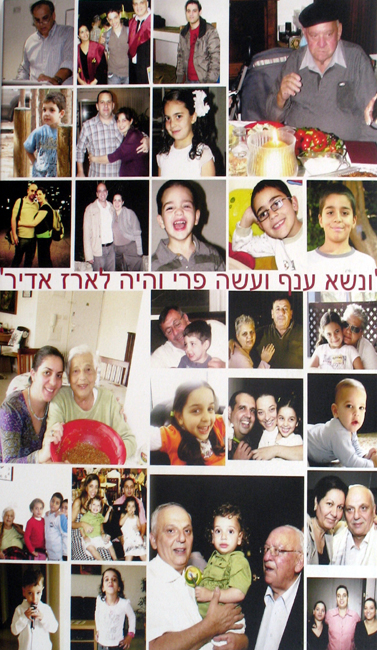

Chaim: We were a big family… everyone went in the crematoria… and I was left all alone. And I always used to say: I want to live in order to tell. Even at my age, I still drop everything and go to bear witness – that's like a holy thing. I think that people have to know, and the story has to be told as much as possible, so that God forbid the same thing won't happen again, because Judaism is something you can't escape from, like I said before: with pain, without pain, with curses, with beatings, but because of the fact that you were born Jewish, you can't escape. There's no way. I was born Jewish and I will die Jewish with pride. I was stubborn and stubbornly I persevered and I raised a family and today I have two boys and a girl and they are named after all those who disappeared…

Itzik: I know that I can't deny three basic elements: my native tongue - nothing helps; my mother - nothing helps; and the place I was born. I tried with all my strength, for forty years, to disconnect from the place I was born. Really, I tried with all my strength…and I failed. Today I acknowledge this. And I have no problem with this, to the contrary. I am a Jew 100 percent, and I'm as good as any other Jew in the world [even if I never regained my faith].

With the help of his wife Esther (of blessed memory), Chaim Raphael established a grocery store in the Levinsky Market in Tel Aviv - a store that became a well-respected delicatessen. Chaim Raphael documented his story in a memoir called The Song of Life (In Hebrew, "Shirat Chaim". The word "Chaim" in Hebrew means life, as well as being Chaim's name –Ed.), thousands of copies of which have been distributed in Israel and abroad. Chaim and Esther have three children and ten grandchildren. His elder son, Zadik Raphael, manages the family business; his daughter Simcha, is a retired teacher; and their son Shmuel, born when his parents were both already older, is a research professor of Ladino at Bar Ilan University.

With his aliyah to Israel, after six months living on a kibbutz, Yitzhak Livnat enlisted in the "Haganah" (the Jewish paramilitary organization during the British mandate period that became the core of the Israel Defense Forces –Ed.) and participated in the War of Independence as a combat signal operator. After the establishment of the Israel Defense Forces, Yitzhak served as a communications officer, and in the framework of his duties trained many other officers. In 1957 he retired from the army with a rank of major, and together with his brother established and managed the haulage company "Ta'avura". Yitzhak also became a member of the managing board of the Museum for the Heritage of Hungarian-Speaking Jews, and remains a supporter of the museum and its development today. Yitzhak and Ilana have four children, twelve grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Four of their children have served in the IDF as officers, and all of them are academics. Parts of Yitzhak's story are described in the book Outcasts – A Love Story, and he continues to give testimony before schoolchildren, at the request of his own grandchildren.

- 1.Chaim Raphael, Song of Life (Tel Aviv: HaMichaber Publisher, 1997), p. 40.

- 2.Ibid., p. 17.

- 3.Ibid., p. 40-41.

- 4.Haim is describing a day that would come to be indelibly etched into the memories of the Greek Jews as "Black Sabbath." On July 11, 1942, all Jewish men were assembled in Eleftheria Square (ironically, the name of the Square means "Freedom" or "Liberty") to be registered for forced labor. They were forced to stand in the sun for hours and were abused and humiliated by the German soldiers, who made them perform various physical "exercises" just to weaken and break them. For more about Greece and the Holocaust in Greece.

- 5.Franz Joseph was Emperor of Austria as well as King of Bohemia, Croatia, Hungary and Galicia at the end of the nineteenth, and the beginning of the twentieth, centuries. He had other titles as well.

- 6.Itzik is referring to the fact that when Jews arrived on the ramp at Birkenau, they were sent either to slave labor or immediately to death by a German who stood on the ramp and pointed "left" or "right". There were Jews who were sent in one direction because they had been picked for slave labor, but refused to be parted from a member of their family who had been sent to the other direction – because they had been sentenced to death. Those who refused to be separated from a family member were often allowed to go with him to their own deaths as well (though at the time they didn't know that this was the significance of the designation "left" or "right"). It was usually of no consequence to the Germans performing the selektion on the ramp whether the Jews standing before them lived or died.

- 7.Because there were no bathrooms in the cattlecars, they turned into huge toilets during the journeys to the camps. Eyewitness testimony given during the Holocaust by Abraham Krzepicki describes the situation: "It’s impossible to imagine the horrors in that closed, airless boxcar. It was one big cesspool. Everybody was pushing toward the window, where there was a little air, but it was impossible to get close to the window. Everybody was lying on the ground. I also lay down. I could feel a crack in the floor. I lay with my nose right up against that crack to grab some air. What a stench all over the car! You couldn’t stand it. A real cesspool all over. Filth everywhere, human excrement piled up in every corner of the car. People kept shouting, 'A pot! A pot! Give us a pot so we can pour it out the window.' But nobody had a pot." Alexander Donat, Ed., The Death Camp Treblinka. A Documentary, (New York: Schocken Books, 1979), accessed July 12, 2012.

- 8.Kanada" was the name, in the language of the prisoners, for an area within the camp of Birkenau in which all the stolen property of the murdered and of the prisoners of the camp was stored. Hundreds of prisoners, men and women, mostly Jews, worked in cleaning, sorting, identifying valuable property and assembling shipments of these items to Germany. The real name of the warehouses was the Effektenlager. The name "Kanada" comes from the association of the warehouses with the great wealth of Canada in the imaginations of the prisoners. Work in "Kanada" was considered to be one of the best in the camp, because while working in Kanada it was possible to "organize" food and property and to trade with them on the black market in the camp. In addition, work took place in a closed area (not exposed to the elements) so that the work was not physically difficult. For these reasons, the number of survivors from Kommando Kanada is relatively high.

- 10.Itzik is referring to an infamous selektion held by Dr. Mengele in Birkenau, about which there are many testimonies. In this selektion, Mengele set up a wooden measuring stick at a certain height. Children who were below this height and were not tall enough to reach the stick with their heads were sent to the gas chambers. Children who were taller were saved.

- 11.Susan M. Papp, Outcasts, A Love Story (Ontario: Dunndurn Press, 2009), p. 173.

- 12.Ibid., p. 173.

- 13.Raphael, p. 58.

- 14.The travelers aboard the Shoshanna were transferred while at sea to the Shabtai Luzinsky, and the smaller boat returned to Italy. The Shabtai Luzinsky continued to Palestine, where it ran aground off the beach at Nitzanim on March 12, 1947, Itzik's 17th birthday. Itzik jumped into the water and swam to the coast, where local residents came down to the beach to mingle with the passengers in order to help them evade arrest by the British. Itzik was herded onto a bus brought to take the illegal immigrants away from the area in order to fool the British.