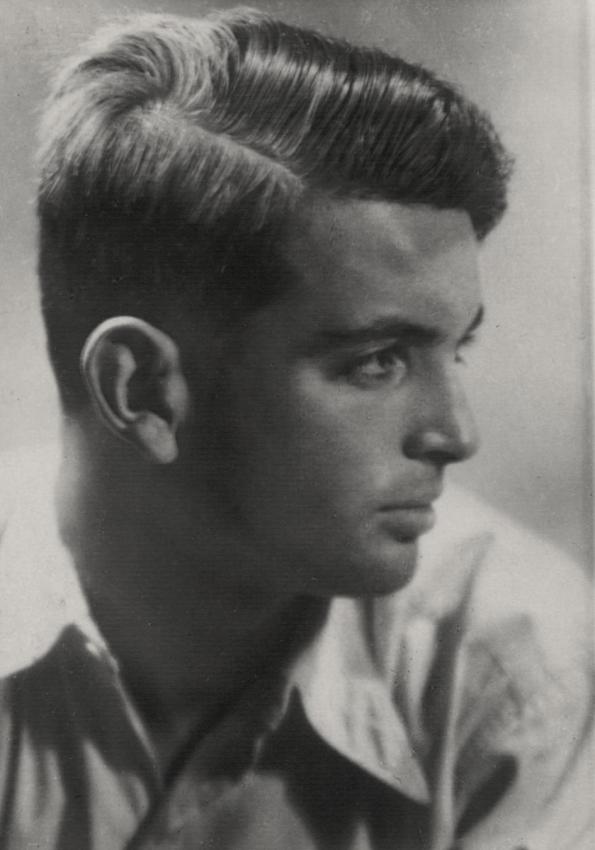

Julius, a youth with a highly developed technical sense and good hands, created pins and knitting needles that served craftsmen in the area, repaired assorted tools and generally found innovative ways to earn a living. In Obdovka he met Menachem Scharf, a youth who had also been deported from Czernowitz, and the two spent many hours together. Menachem was impressed with his resourceful friend with the golden hands, who also skillfully crafted chess pieces for them to play with. "I knew how to play a little" said Julius when explaining why he made the chess pieces, "and it allowed me to be with myself, to dream, to dream of beautiful things, of good things… it was a psychological instinct… at some time in the future life would have to be good."

One day Julius was caught and sent to a camp where the forced laborers repaired German military equipment. His task was to care for the horses that hauled the disabled vehicles. In his testimony he describes the attitude of the German soldiers: "I was garbage, they were the masters", but he adds that there were also soldiers who would walk past the children who worked in the camp and secretly leave them slices of bread with some kind of spread. Thanks to Julius's work in the camp, he was privy to sensitive information that he passed on to partisans who asked him to report on what was happening inside the camp. "My revenge" he said, "was that I could report that a train packed with military equipment was leaving the camp, and that the train then exploded and burned."

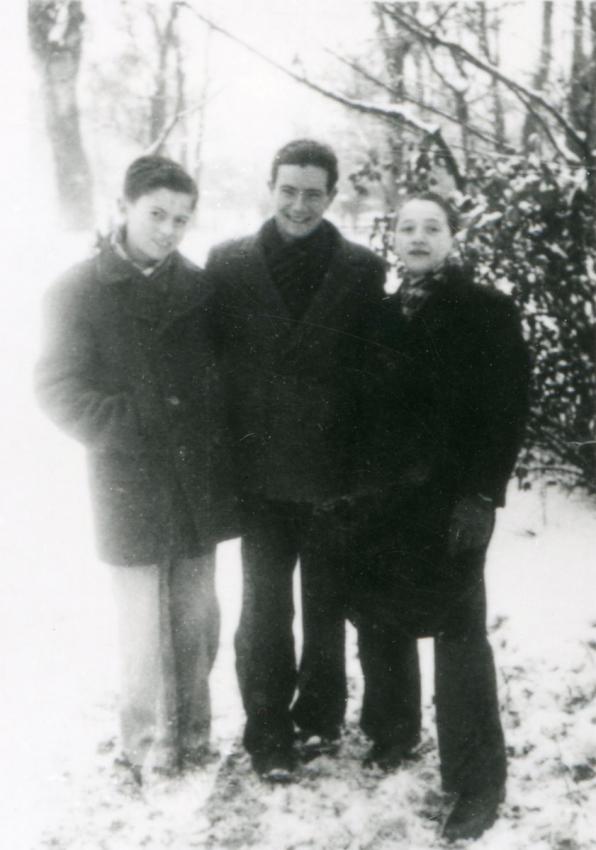

In the winter of 1943, Red Cross representatives came to the area and collected children and youths up to age 15 with the intention of sending them to places with better living conditions. After trudging 70 km through the snow to Balta, the children, among them Julius and Menachem, were told that there was not enough room on the train for them all.

Menachem was included among those who continued on the train to Bucharest, but Julius was left at the station. Before they parted Julius gave Menachem the chess set as a memento of their friendship.

The children who had been left at the station were offered passage on a boat along the Dniester River to Nikolayev port and from there on to Switzerland. Most of the children who chose this option ultimately perished, but Julius was among those who chose to return to Obdovka where he was reunited with his mother. After the war the two returned to Czernowitz and immigrated to Israel in 1975.

Menachem Scharf came to Eretz Israel (Manadatory Palestine) soon after the end of the war without knowing what had become of his friend Julius Druckman. He donated the chess game that his friend had made during the war to Yad Vashem for display in the "No Child's Play" exhibition in 1997.

Soon after the exhibition opened, a relative of Julius came to view it and told Julius that the chess set he had made was displayed at Yad Vashem. When he came to see it, he introduced himself to the museum staff.

Thus, 50 years after the two youths had parted on the platform of the train station in Balta, their chess set brought them together again.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection,

Donated by Menachem Scharf, Israel