The grave markers are inscribed with the names of the victims, their place of birth and their ages. The careful recording of the details of each victim is the work of Stephan Kolb (1886-1945), who served as the gravedigger of the Jewish cemetery of Djakovo from 1910 until 1945. Throughout the war he kept a detailed account of the burials that enabled the marking of the graves after liberation.

With the invasion of Croatia on the 6th of April 1941, the Germans divided the occupied territory with their allies: Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary and the Independent Croatian State - NDH. The Ustasa, a nationalist and separatist Croatian organization that employed terror tactics, were given control of Croatia, where they proceeded to discriminate and persecute religious and ethnic minorities. For their purposes they set up concentration and death camps, among them Jasenovac, Stara Gradiška,Jadovno, Loborgrad, as well as camps on the Islands Pag and Kruščica.

In December 1941, the head of the Jewish community in Osijek received orders from the Ustasa to find a suitable place to serve as a concentration camp for Jews. The place that was chosen was a flour mill in Djakovo. Its prisoners were women and children. On the morning of the fifth of December, the first transport of 1,197 children arrived from Sarajevo. The second, with 668 Jews from Bosnia arrived on the 22nd of December. Six hundred women and children sent to the camp between December and July 1941 mostly from Bosnia and Herzegovina perished.

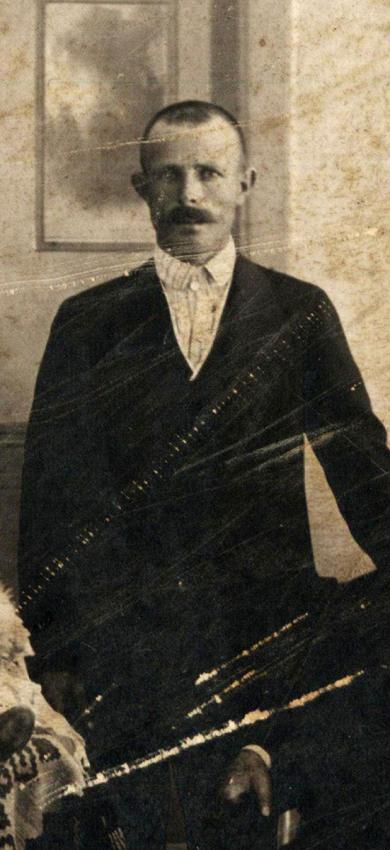

The camp was initially run by the Jewish community of Osijek., but at the end of March 1942, the camps administration was transferred to the Ustasa. The next three months saw a drastic deterioration of the conditions. The guards employed violence towards the inmates and the sanitary conditions worsened, resulting in a sharp increase in the mortality rate. The Jewish committee, now under direct control of the Ustasa, was forced to deal with the spiraling amount of burials and they approached Stephan Kolb, the Jewish cemetery’s gravedigger to make the arrangements. According to Kolb’s meticulous records, on the 9th of December 1941 the first victim buried was Mazlata Katan, aged 65 from Sarajevo. Kolb transferred the body to the Jewish cemetery for burial. He continued from then on to record each burial spot carefully along with the date of burial and details of the deceased. He did so until the dismantling of the camp.

The camp was dismantled in July 1942. The 2,400 women and children who remained alive were sent in three separate transports to Jasenovac camp where they were murdered upon arrival.

Kolb retained his record book of the burials from the camp. Thanks to his careful records of each burial, including the row, and personal details of the victim, it was possible after the war to mark the graveswith grave markers, revealing the total number and details of the victims of Djakovo camp.

In the decades after the war, when many Jewish cemeteries throughout Yugoslavia were left abandoned and left to decay with no Jewish community left to tend them, or worse still, wantonly destroyed by local vandals, the cemetery at Djakovo was well tended. From 2007 the city has taken over the care of the cemetery as evidence of the horrors that took place there.

The five grave markers that were donated by the Jewish community of Sarajevo to Yad Vashem will be preserved in the Museum’s artifacts collection as a memorial to the women and children who were victims of Djakovo camp.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by The Jewish Community of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, courtesy of Lea Maestro, Project Coordinator of the Project for Restoration of the cemetery of the victims of the Djakovo Concentration Camp