Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

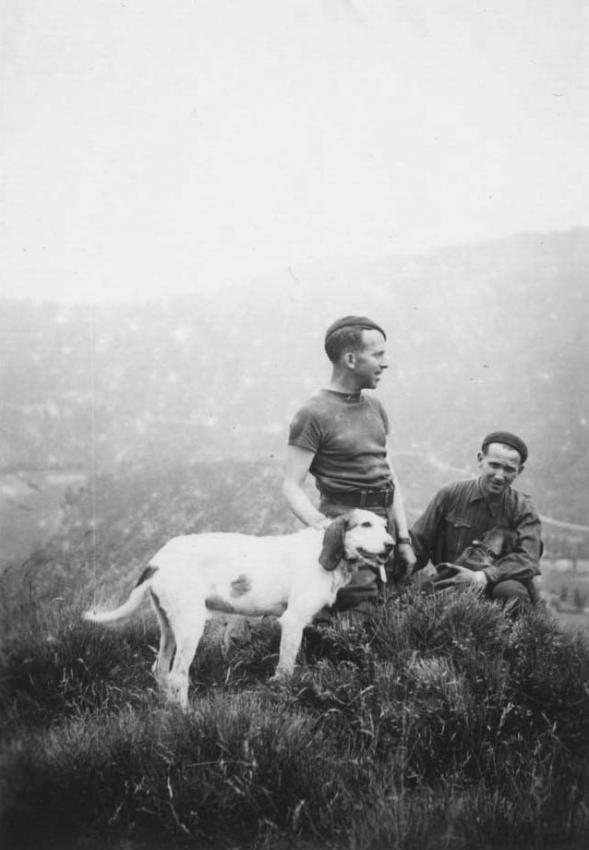

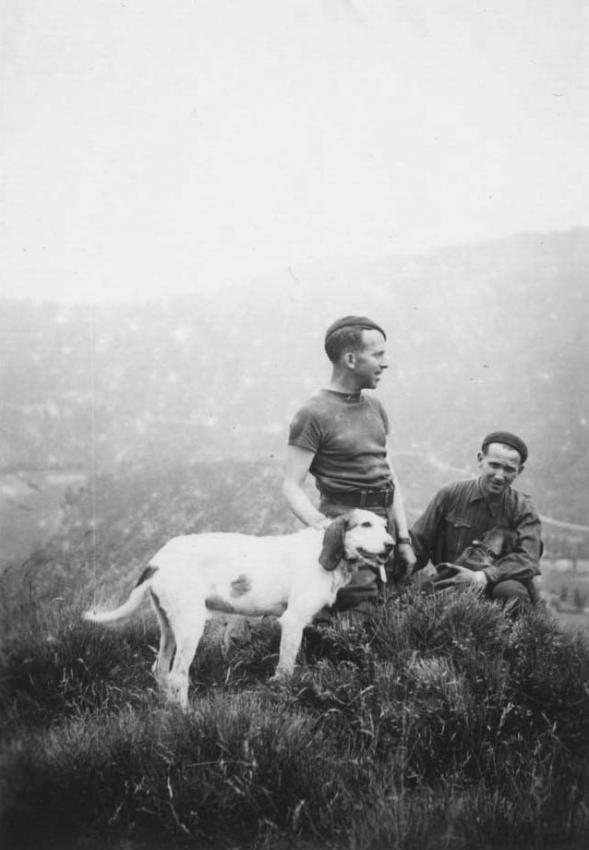

Alexander Mayer, born in 1910, was deported to Auschwitz from the Drancy camp in France. His arm was tattooed with the number B 3865 on his arrival at Auschwitz, and he was assigned to forced labor.

In the winter of 1944, Mayer was hospitalized in the camp infirmary, where he remained until the camp was liberated by the Red Army.

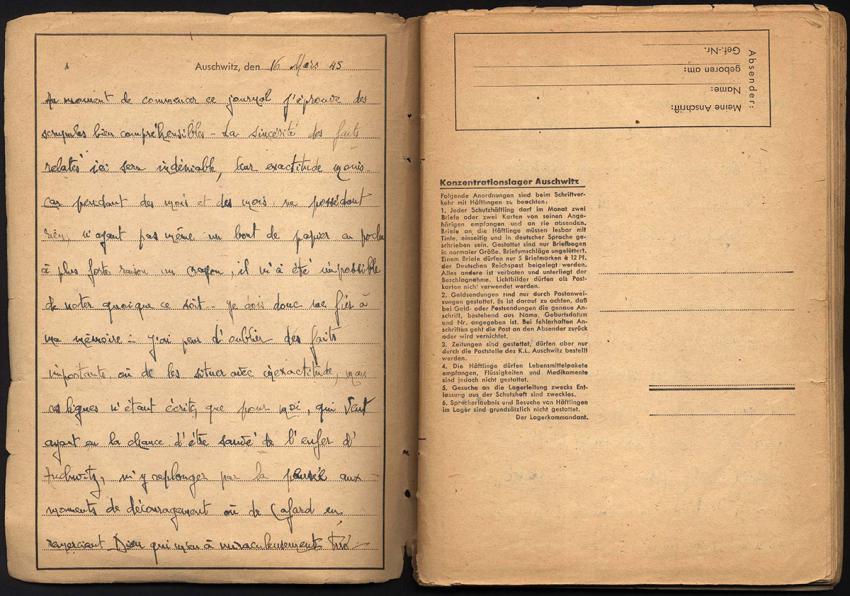

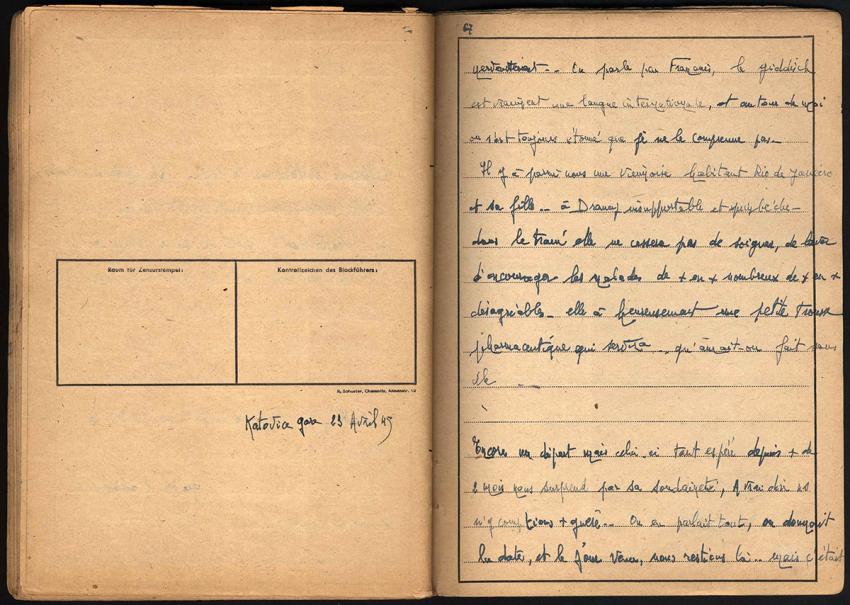

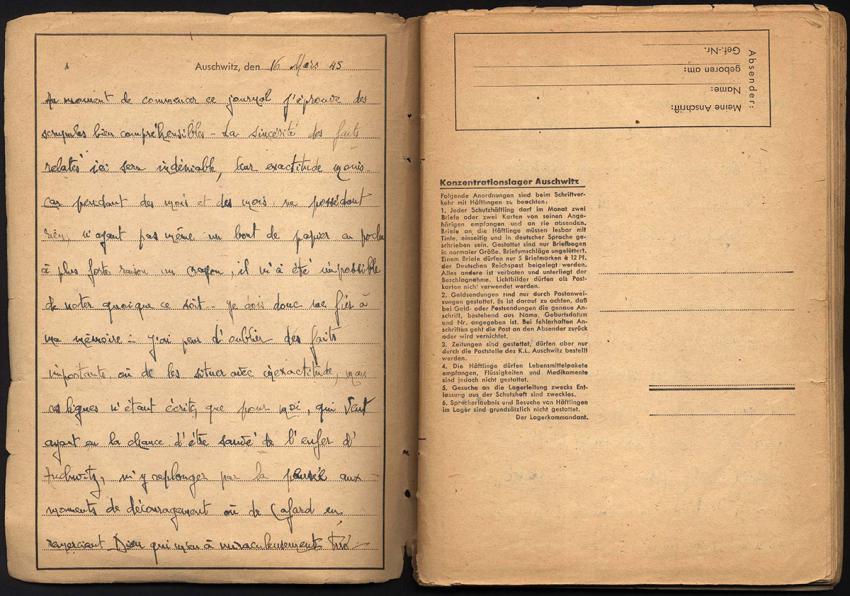

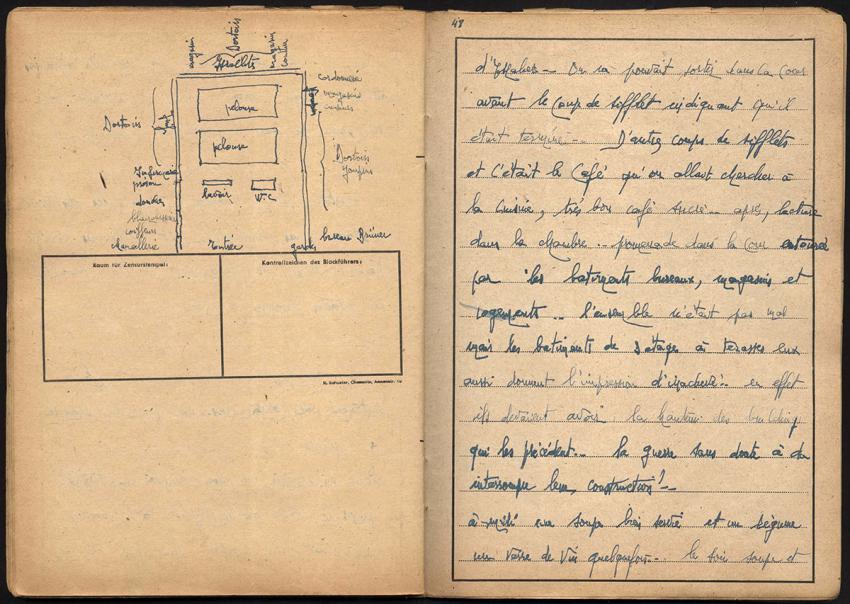

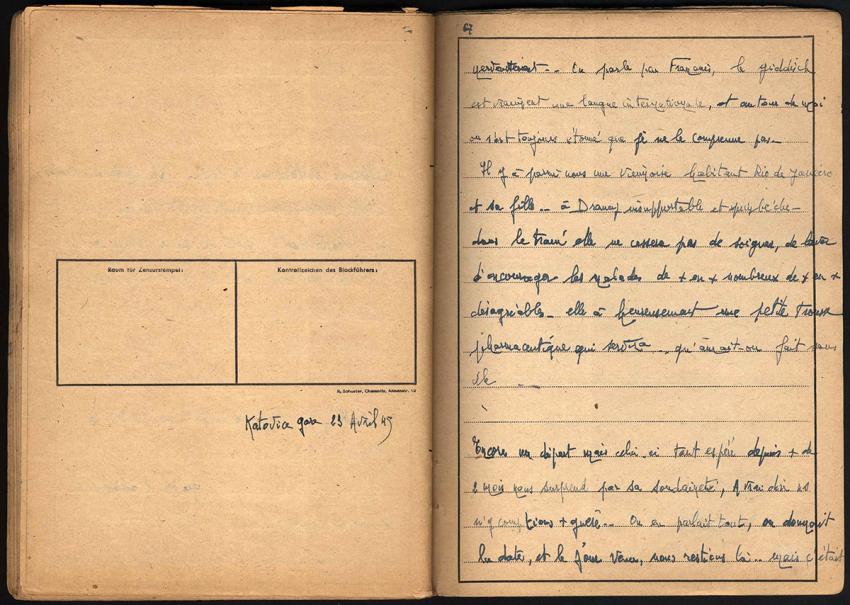

In the period between the flight of the Germans from the camp and Mayer's departure from Auschwitz, Mayer found some blank forms belonging to the Nazi camp administration, and after long weeks of recovery and recuperation, he managed to gather the strength to begin to write about his experiences during the war.

The entries in his diary begin with a description of the day he was caught in France and deported to the Drancy camp. He describes the period he was detained in Drancy, the trip by train to Auschwitz, and the five-month-long journey back to his home from Auschwitz after the liberation - to Odessa and then by ship via Turkey to France. Later on, he describes the suffering and the atrocities endured by the prisoners in the camp on a daily basis and the chaos during the period just before the liberation.

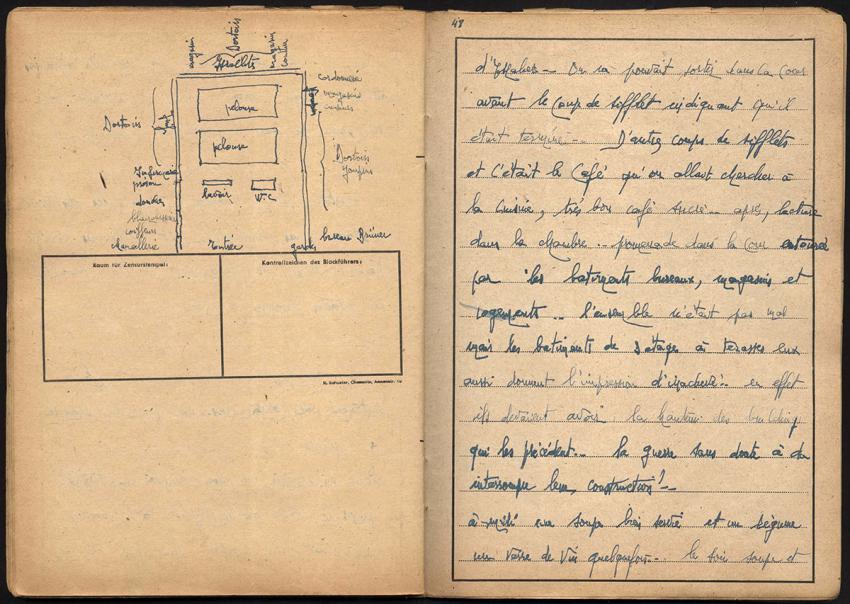

The forms on which the diary is written served as stationery for political prisoners. On one side of the page there are lines for writing, while on the other side there are detailed directions for the prisoners regarding the permitted content of the letters, with room for the signature of the head of the block.

From Alexander Mayer's diary:

"The battle is at its height, 27 January, a historic day.

First, preparations were made by the Artillery Corps that lasted until the afternoon. The air thundered. We could clearly see the rockets passing over the camp; entirely by chance they did not hit us. In the afternoon, from my bed I could see some stains that were brighter than the snow on one of the roads leading to the camp. The Russians were dressed in white, but the sun cast their shadow up to the wall of the camp. They reached there quickly, sometimes running, sometimes crawling, taking shelter behind the trees.

Afterwards, without losing any time, they entered the camp, after several well-aimed shells made a breach in the wall. Our rescuers were quite astonished when they saw these creatures, half naked or dressed in an extremely illogical way, hurrying to greet them and hanging on their necks. But [the creatures'] very gauntness must have calmed them. One officer told me afterwards that they had thought that the camp was empty, because along the entire way many bodies in pajamas marked the hasty route of the Germans' retreat. Something extremely astonishing was then seen in Auschwitz: the ‘Häftlings' (prisoners) who had tasted too much vodka staggered through the streets, to the delight of the Soviet soldiers.

And they, who had already divested themselves of their white capes, astonished us with their beards, their mustaches. The Red Star stood out on their fur hats. And there were female soldiers, similar to the male soldiers, armed as they were, and driving mules hitched to sleds. They surrounded us, as surprised as we were. And already we were "tovarish" (comrades).

… For two days I took advantage of the sunshine to go and wash in the snow. I was rather weak, but how can I describe my joy that once again I was free, that once again I could walk without holding myself at attention among the Blocks. That it was good to sit myself down on one of the benches on the perimeter. This was the first time that something like this had happened to me, and in the observation towers it was Soviets who were standing guard."

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection,

Loaned by Georges Mayer, Ra'anana

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue