Avraham-Adolf Hellmann was born in Lencica, Poland in 1882. In 1918 he married Charlotte nee Wohlmuth and the couple settled in Nikolsburg (today Mikulov, Czech Republic). Avraham served as Head Cantor in the community as well as being the founder of the Jewish Museum of Bohemia & Moravia in the city. The Hellmanns had three children –Max-Mordecai, b. 1919, Lilly, b. 1921 and Edith-Rina, b. 1923.

Avraham Hellmann’s name became known to us initially, from an exemplar of a Jewish calendar for 1944 made in Theresienstadt that has been in the artifacts collection since the early years of Yad Vashem’s existence. The calendar was duplicated using a blueprint technique (indeed an additional copy is in the Yad Vashem Archives). The cover of the calendar is illustrated with the 12 Zodiac signs accompanied by the Hebrew names of the months, and a title. The back cover is illustrated with a synagogue interior. Inside the booklet are additional illustrations, among them the image of a man standing at prayer in the synagogue with the signature of the artist “Berlinger”. Asher Berlinger, like Avraham Hellmann, was a cantor in his community – Schweinfurt, Germany, and there is a basis to assume that the two Chazanim had contact with one another in Theresienstadt.

On the last page of the calendar there is a handwritten signature: “ Avraham Hellmann in Theresienstadt”. Opposite, pasted on to the back inside cover is a watercolor painting of a synagogue interior below which is written ““in all the [Jewish people’s] places of exile, the Divine Spirit was with them” (Jerusalem Talmud, Ta’anit 1.1). Beneath is written “Sudetenkaserne Synagogue”

With the annexation of Nikolsburg by the Nazis in 1938, the local Jewish community, including the Hellmann family, was given twenty four hours to leave the city. Avraham and Charlotte, with their two daughters and Charlotte’s elderly mother, left for Brünn, where Max was already living as a student. Prior to his departure, Avraham Hellmann found places for the residents of Nikolsburg’s Jewish Home for the Elderly in other communities. He then proceeded, together with Prof. Engel, to move the Museum collection to Brünn. The collection did not escape the eyes of the Nazis and in a short time; Avraham was forced to catalogue all the items under supervision of the Gestapo. With the help of his daughter Lilly, they packed the items and delivered them to the Archives in Prague. [This collection is today part of the collection of the Jewish Museum of Prague].

In Brünn, Avraham worked with the Jewish Committee that extended aid to the Jewish refugees, but on December 2nd, 1941, the Hellmanns were deported along with their daughter Lilly to Theresienstadt. Their eldest son and younger daughter had managed to leave and settle in Eretz Israel.

In Theresienstadt an internal Jewish administration managed to maintain order in spite of the tight supervision of the Nazis. The Nazi propoganda machine exploited the well run functioning of the ghetto in order to cynically present it as a model resettlement of Jews, thus using it as part of their camouflaging of their mass murder policy.

In spite of their growing awareness of the cruel irony of their situation, the Jews of Theresienstadt recognized and cooperated with the actions of the leadership of the ghetto, viewing their functioning as an expression of spiritual resistance to the Nazis.

From the testimony of Charlotte Hellmann-Lederer, who filled out a Page of Testimony for her husband Avraham-Adolf Hellmann, one learns of the many activities of her husband both before the war and in the ghetto. Charlotte survived thanks to her inclusion among the group of workers in the Glimmerwerke a factory for the splitting of mica, a material essential to the German war effort.

From the onset of his arrival in Theresienstadt, Avraham Hellmann became involved in community affairs, as he had done before the war. An important area that he was involved in together with Rabbi Siegmund Unger, one of the leading rabbis in the ghetto, was as a member of the Chevra Kadisha.

Charlotte relates how already with the first deaths, Avraham, along with three others, approached Edelstein, the head of the Judenrat and entreated him to ask the German head of Theresienstadt to allow the opening of a Jewish cemetery across from the Russian WWI cemetery. Avraham Hellmann continued his activities in the Chevra Kadisha until his deportation from Theresienstadt in 1944. The testimony includes a description of how they made coffins from potato crates, and how they initially transported the corpses by sled and then with wagons that had served as hearses that many of the communities had brought with them to Theresienstadt. At first, the dead received individual burials, then eight were buried together. As the death rate soared, a crematorium was built. Avraham kept a written account of the dead and their remains were preserved in urns.

Charlotte relates further:

“Even in the morgue, the dead were treated with respect. Each body was washed according to Halakhic precepts and a detailed list was made. Each listing included the name of the deceased and his number in the transport he had arrived in. Until my husband was deported on the first of 11 transports in the fall of 1944, 35,000 dead were listed.”

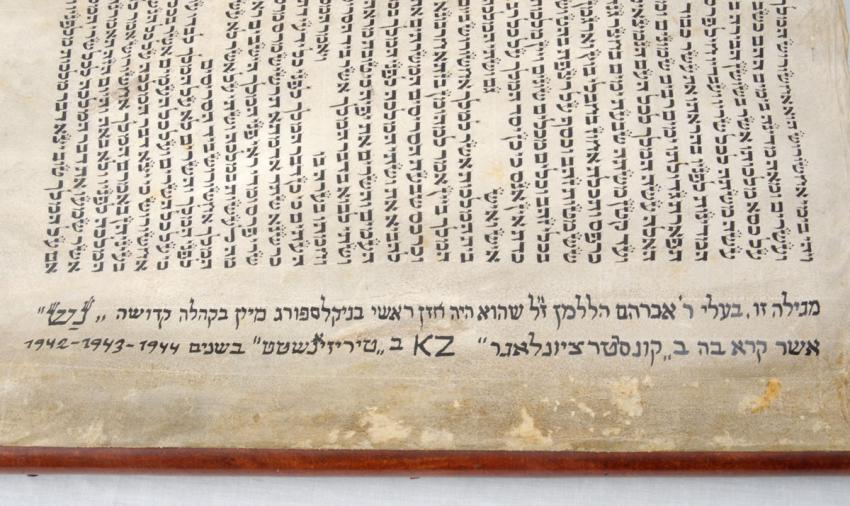

After her husband’s deportation on the 28th of September 1944, Charlotte kept his belongings, among them a Shofar and a Scroll of Esther that he had brought with him to Theresienstadt and that had served the community of Jews in the ghetto. From other testimonies we learn that many communities brought with them Torah Scrolls, Megillot, Shofarot, Menorahs and Kiddush cups and that religious services were held in many places in the ghetto. Avraham Hellmann served as a cantor for services held in the Sudetenkaserne Synagogue and the shofar and Scroll of Esther that he brought with him served those who prayed there.

After the war Charlotte wrote in scribe’s lettering at the beginning of the Scroll of Esther:

“This Megillah, my dear husband Avraham Hellmann of blessed memory, who was the head cantor in Nikolsburg in the community of “Nash”, read from in Theresienstadt concentration camp in the years 1942-1943-1944.

Charlotte could not bring herself to part from the Megillah, thus only in 1972, two years prior to her death, she donated it to Yad Vashem.

Having uncovered the various details about Avraham Hellmann through Charlotte’s testimony, we learned that the Shofar that has been in the collection in Yad Vashem since the 1950’s was the same that Avraham had used in Theresienstadt.

In Charlotte’s testimony there is a moving account of the Kol Nidre prayers that Avraham Hellmann led on the eve of Yom Kippur 1944 as he stood with two thousand other men on the ramp waiting for the transport that was to take them to Auschwitz – for most it was to be their final journey. Our research revealed that not only was Avraham Hellmann among the deportees, but also the cantor Asher Berlinger, mentioned above:

“It was Kol Nidre eve. My husband said: “It's time to pray”. He placed two suitcases one on top of the other and covered them with a Tallit; He stood with Levin and his son from Komotau in Bohemia and the three put their prayer shawls over their heads and when my husband began to pray out loud, a bitter cry rose from the throats of all the men and women. One who was not there cannot even imagine it. It is necessary to understand that most of the Czech Jews were not religious….So things continued until the next day-Yom Kippur…for two days with no sleep. People sat on their cases. During Yom Kippur whoever wanted to joined the prayers. My husband chanted the “U’Netane Tokef” and an old man, apparently a Rabbi from Slovakia removed his shoes and recited in a fearful cry- Vidui (confession)…

The women returned to their rooms but we couldn’t sleep. We waited for the sound of the train’s departure. At 6 a.m. we heard the train’s whistle."

Charlotte left Theresienstadt on July 6th 1945 and returned alone to Brünn. There she learned of the tragic fate of her daughter Lilly who was deported from Theresienstadt in October 1944 on a women’s transport that went through Auschwitz to Kurzbach Camp in Silesia. From there the women were marched to Gross-Rosen and finally to Bergen-Belsen. Lilly was liberated there but died of typhus a short time after the liberation.

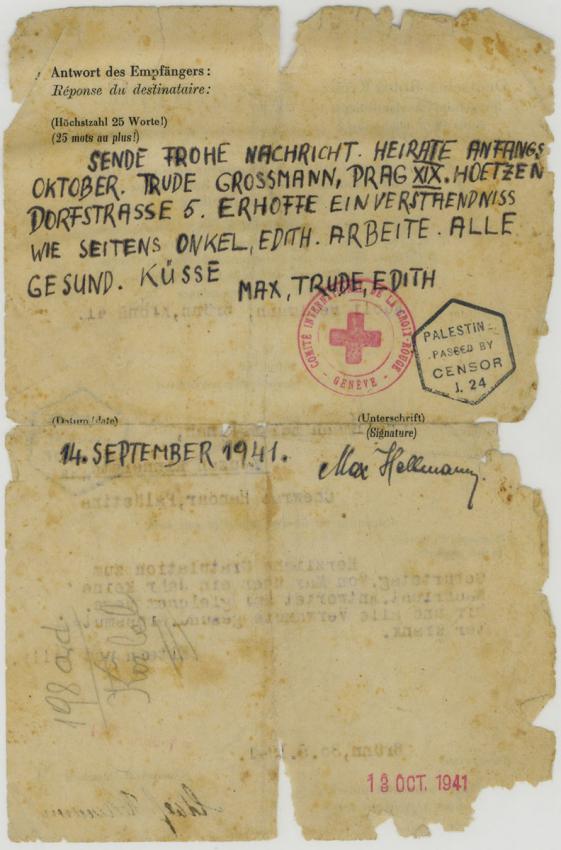

In 1946 Charlotte was able to join her two surviving children in Eretz Israel. The Hellmanns had managed to send their youngest daughter Edith-Rina on Youth Aliyah at the beginning of 1939. Their 19 year old son, Max, who was active in a Zionist youth movement, was able to leave Brünn with the Nazis literally on the doorstep with a group of youths who managed to enter Eretz Israel in defiance of the British mandate restrictions.

After a number of years, Charlotte remarried. Her second husband, a Czech émigré like herself named Julius Lederer, had managed to come to Eretz Israel in 1939.

Charlotte Hellmann-Lederer passed away in 1974. The Yad Vashem Museum staff recently managed to locate her grandson Micah, son of Max & Trude Hellmann, who donated further artifacts and documents as well as information that allowed us to tie up all the loose ends of the story and to finally prove what had been conjecture until that point, that the Jewish calendar in the collection with Avraham Hellmann’s inscription, was indeed donated by Charlotte Lederer when she donated the Shofar in the 1950’s.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Gift of Charlotte Hellmann-Lederer, Tel Aviv