Abraham Van Oosten, a gifted architect with a distinctive style, designed homes in the 1920s and 1930s using modern techniques that combined elements of traditional rustic style with modern architecture. Many of the homes he designed included stained-glass windows. Some of these homes have since been recognized as preserved historic buildings due to their unique character.

One of the projects van Oosten worked on in the beginning of the 1930s was to create stained-glass windows for the synagogue in Assen, northeastern Netherlands, where he and his family lived. The windows were completed and installed in 1932, as attested to by the inscription engraved upon them. Five years later, van Oosten died at the untimely age of 40. His widow, Heintje, and their three children, Gonda, Leo and Johanna, remained in the town.

In 1940, the Germans occupied Holland and imposed anti-Jewish legislation throughout the country. Leo van Oosten was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. In October 1942, the Jews of Assen were rounded up and deported to the Westerbork transit camp, among them Heintje and her daughters, Gonda and Johanna.

In Westerbork, Gonda married Asher Gerlich, a Zionist pioneer. In 1944, the couple was deported to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. Gonda's mother, Heintje, and younger sister, Johanna, were sent to Auschwitz, where they were murdered.

Despite the terrible conditions in Bergen Belsen, Gonda and Asher managed to survive . In April 1945, just prior to the end of the war, the Germans sent a large group of prisoners, including the young couple, by train to an unknown destination, known as the Lost Train. Soviet troops stopped the train en route at Troebitz in Germany, and released the prisoners.

The sole survivor of the Van Oosten family, in 1946 Gonda changed her first name to Tamar and together with Asher, immigrated to Eretz Israel. The couple joined a group of young Palmach pioneers and established Kibbutz Beit Keshet in the Lower Galilee. They had seven children.

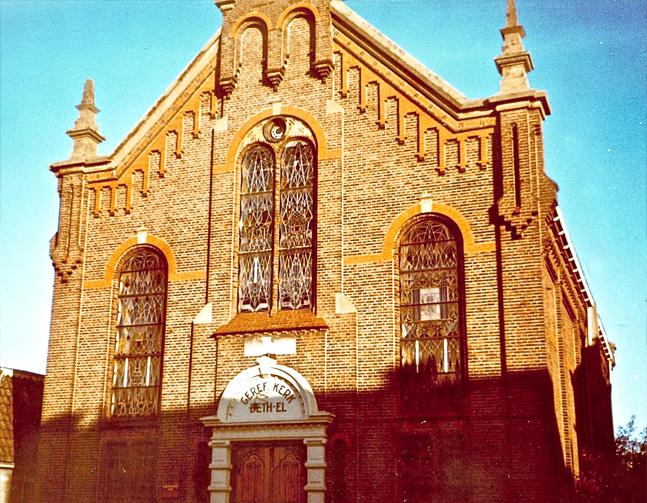

Most of the Jews of Assen did not survive the Holocaust. A few returned, but they were not able to reestablish a Jewish community and the synagogue was never reopened. The building was eventually purchased by the local Protestant community and converted into a church.

In 1974, Tamar Ben Gera (Gonda Gerlich-van Oosten) learned that the former synagogue was to be demolished. She decided to work to save the stained-glass windows her father had designed, and bring them to Israel. In a complicated logistic operation, a number of the decorative windows were dismantled and sent to Israel, where they were installed in the renovated dining hall of Kibbutz Beit Keshet. Depicted in the center of one of the stained glass windows is a shofar (ram's horn traditionally blown during the Jewish New Year); in the center of another is a sukkah (traditional booth in which Jews reside during the Succot holiday) and beneath it the four species (waved during the Succot holiday)– a lulav (palm branch) flanked by myrtle and willow branches, and an etrog (citron).

With the changes in kibbutz lifestyle over recent decades, the dining hall ceased to be the central meeting place of Kibbutz Beit Keshet. With a mind to preserving Abraham van Oosten's stained glass windows, Ben Gera recently approached Yad Vashem to help move the windows from the dining hall and transfer them to the Mount of Remembrance, where they may be preserved for posterity.

Today, the colorful stained-glass windows are housed in Yad Vashem's Artifacts Collection, where they serve as a memorial to the impressive synagogue of Assen that no longer exists, to the Jewish community of Assen that was destroyed, and to the family of Abraham van Oosten – his parents, his widow and two of his children, who were murdered in the Holocaust.

Yad Vashem, Artifacts Collection

Donated by the family of Tamar (Gonda) Ben-Gera (van Oosten), Israel