After France capitulated to Germany, the Vichy government led by Maréchal Pétain collaborated with the Nazis in the deportation of Jews. On August 26, 1942, at the height of the deportations, Pierre-Marie Théas, Bishop of Montauban, following the example of his neighboring colleague, Archbishop Saliège of Toulouse, issued a pastoral letter condemning the deportations of Jews. Speaking without any ambiguity, Théas declared:

"In Paris, tens of thousands of Jews have been treated with the utmost wild barbarism. Even in our own regions, one witnesses a disturbing spectacle: families are uprooted; men and women are treated as wild animals and sent to unknown destinations, with the expectation of the greatest dangers. I hereby give voice to the outraged protest of Christian conscience, and I proclaim that all men, Aryans or non-Aryans, are brothers, being created by the same God. [I further assert] that all men whatever their race or religion, have the right to be respected by individuals and by states. Hence, the recent anti-Semitic measures are an affront to human dignity and a violation of the most sacred rights of the individual and the family."

To make sure that his message of vehement opposition would have the desired impact, it was imperative that it be read from the pulpits of all of the many churches in his diocese. Thus, Théas turned to Marie-Rose Gineste, a long time activist in Catholic social work, to see to it that the pastoral letter be replicated and delivered in time to be read from the churches’ pulpits the following Sunday, 30 August 1942.

“It was with great enthusiasm that I accepted this mission,” Gineste recalls.

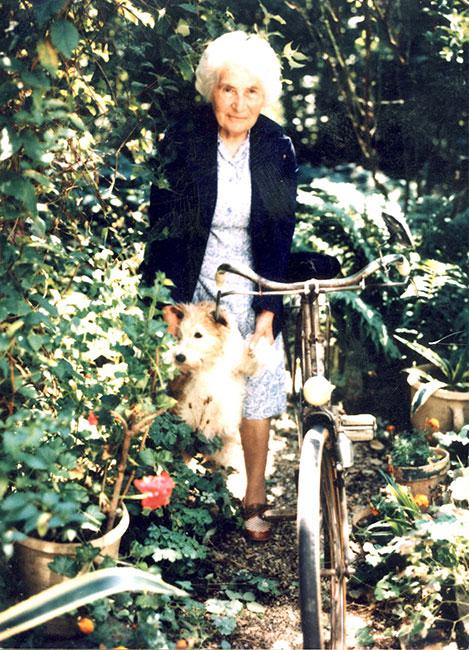

She told the bishop that it was not advisable to send the letter through the post office, for the Vichy authorities would surely censor it. Instead, she “proposed to take the letter herself by bicycle and deliver it to all priests and all parishes of the diocese.”

Thus all parishes of the Montauban diocese received Bishop Théas’ letter of protest, and delivered the pro-Jewish sentiments from their pulpits on the following Sunday (with the exception of just one parish, whose priest was a known Vichy sympathizer). The echo of Théas’ pronouncement, following that of Archbishop Saliège a week earlier, shook the ramparts of the Vichy establishment, and according to many historians, marked a turning point in the Catholic Church’s earlier passive attitude toward Pétain’s government. It also acted as a signal to all Frenchmen to go forth and protect Jews from deportation.

Impressed by her singular devotion to this cause, Théas charged Gineste with the tasks of finding shelter for Jewish children and adults at various religious institutions in the region and of supplying them with false identities. Gineste also obtained critically needed ration cards from government warehouses and offices or received them from sympathetic government officials, and worked together with Jewish clandestine associations in order to distribute the ration cards to Jews in hiding.

After the war, Gineste cited the motivation behind her heroic deeds as an expression of her Christian belief:

“Since my childhood Christianity has dominated and oriented my entire life—before the war, during the war, during the occupation, and afterwards until this day... in my various and numerous deeds, and all the days of my life.”

In 1985, based on the many testimonies in her favor, Marie-Rose Gineste was awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. Bishop Théas had been similarly honored with the title in 1969.

Since the end of the war, Gineste has kept and cherished the bicycle, as a memento of the fateful days when it served to disseminate this vital message. In her 89th year, she asked that this historic bicycle be turned over to Yad Vashem for permanent safekeeping.

Thus, a poignantly worded denunciation of the deportation of Jews by a high-ranking French Catholic cleric—words so sorely lacking in those days — helped galvanize a considerable segment of French public opinion in favor of assisting the Jews. It would not have been possible without Marie-Rose Gineste and her nondescript, rickety bicycle.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Gift of Marie-Rose Gineste, Montauban, France