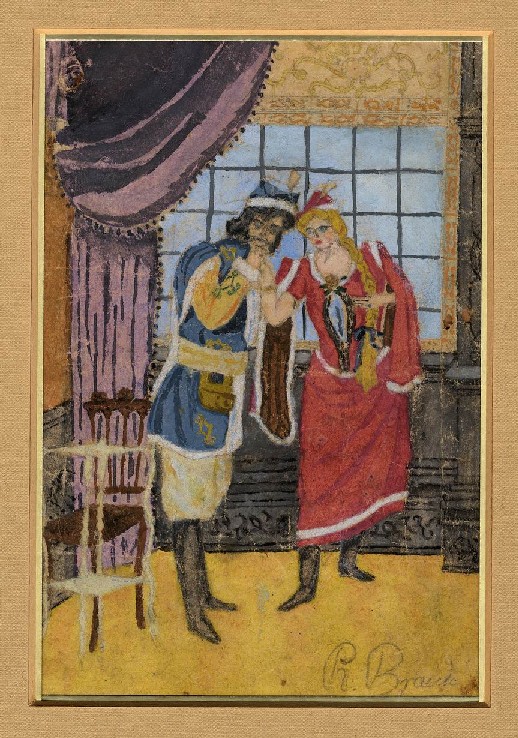

Nobleman kissing the hand of a Lady, probably a scene from Aleksander Fredro’s play “The Revenge”, 1943-1944

Check out this article from Bloomberg on the San Francisco Chronicle about art that was created during the Holocaust by a little girl in hiding, and that has now gone on display at the Museum of Holocaust Art at Yad Vashem.

By GWEN ACKERMAN Bloomberg

Israeli artist Maya CohenLevy is speaking animatedly when she catches her breath and her eyes fill with tears. She’s just noticed four, colored sketches framed on the wall in front of her – drawn by her mother as a 12-year-old hiding alone from the Nazis in a Polish widow’s cellar.

“This shook us up,” she says, recalling the story behind the sketches, on display for the first time after being donated to Yad Vashem Museum of Holocaust Art. “It’s like we were living on the edge of a chasm and suddenly we had to look in.”

Renata Braun, who faced death if discovered by the Germans, stayed in a basement in 1943 and 1944. While fugitives such as Anne Frank wrote, Renata was calmly working with pencil, gouache and watercolor. She copied photos of people she no longer saw from the family album, and scenes from a book of the Polish epic poem Pan Tadeusz. Each sketch is highly detailed and neatly signed in the corner.

The pictures arrived this month at the museum in Jerusalem after director Yehudit Inbar happened to notice a short mention of the drawings made by Cohen-Levy during an interview with an Israeli newspaper.

“I was so excited because there are no such finds like this today from the Holocaust period, especially those of children,” Inbar says of the day she came across the sketches mentioned in the paper. “Children were hidden in very difficult circumstances. An adult can save things, but a child? Here we have a girl, a talented girl, and she saves these drawings and takes them with her.”

Yad Vashem research led to testimony Braun gave between 1945 and 1947 that is kept in the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland, with a copy in the Yad Vashem archives. The documents gave Cohen-Levy and her siblings their first peek into the childhood of their mother, who died, aged 38, after refusing to speak for years about her past.

The children found the sketches – which she only showed to her husband once – in an attic.

In the testimony, Braun describes life in Nazi-occupied Poland, the arrests, fires and being forced to leave her childhood home. She tells of how, once her parents finally decided to reunite and flee, they failed to show up for a meeting with the Polish woman who was hiding their daughter and were presumed killed.

“I never heard from my parents again,” the testimony says.

There are no accurate statistics on how many children survived the Holocaust, in hiding or otherwise, although it is likely the large majority hidden in eastern Europe did not, Yad Vashem says, citing historical evidence.

Braun’s seven drawings were on ordinary paper scraps, one of them with musical notes written on the back. All were put on permanent loan to the museum, though not all were in good enough shape to be restored.

Curator Eliad Moreh attributes Braun’s survival, in part, to her love of art.

“All alone, the young girl went back to the warmth of her home, to what she had learned and it was the culture that gave her the strength to continue,” Moreh says. “It is so strong that it becomes her anchor.”

On the eve of World War II, Braun’s home city of Lvov was the third-largest city in Poland and home to about 100,000 Jews, most of whom were merchants, manufacturers and artisans.

Between June 1941, when German forces entered the city, and July 1944, when the Red Army took control, most of the Jews had been killed, according to the Yad Vashem Encyclopedia of the Ghettos during the Holocaust. The area is now Lviv in western Ukraine.

“I always looked at Yad Vashem from afar, as a national symbol, an institution, somehow not connected to me,” Cohen-Levy says. “Now I see how, without these people, I wouldn’t have a story.”

After the war, Braun moved to Israel, changed her name to Rina Levy, married, had three children, became an artist and died in 1969. She didn’t speak of the time in hiding or the Holocaust, says Cohen-Levy, a painter and sculptor.

“I was 13-and-a-half when she died,” Cohen-Levy says.

“All I can say is that she believed in art as if it was something bigger than anything else.” Cohen-Levy’s father held a canvas for her mother as she lay dying in bed just so she could continue to paint. “In some way, I felt I had to continue painting for her.”