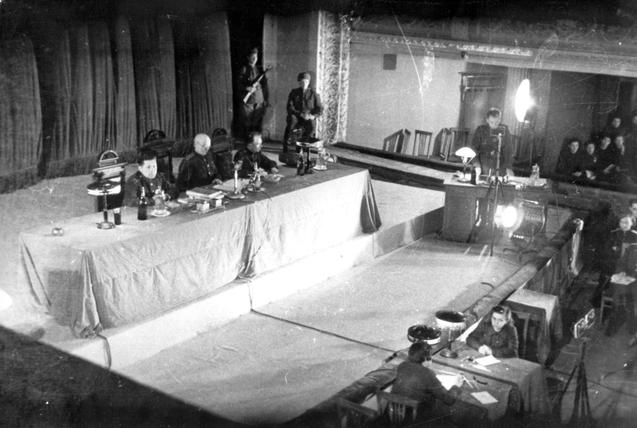

Just published, the articles in Yad Vashem Studies 41:1 address people’s decisions and actions during the Shoah. Two authors published in this volume, Yuri Radchenko (Ukrainian auxiliary police in Kharkiv) and Stefan Klemp (German police in Northern Italy) found that mundane interests motivated most of the Nazi and collaborator policemen to willingly participate in genocide.

Radchenko was able to access previously untapped archival material in Kharkiv in order to present a profile and analysis of the Auxiliary Police in this region of Eastern Ukraine that was never attached to the Germans’ Reichskommissariat Ukraine administrative region. Radchenko finds that the various Ukrainian and Russian nationalists who tried to infiltrate and influence these forces met with only limited success. Interestingly, the competing and sometimes battling factions of the Ukrainian nationalist OUN in Western Ukraine often worked together in Kharkiv, almost as though they were unaware of the rivalry and animosity between the two groups. As elsewhere, the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police in this region were deeply involved in the persecution, spoliation, and murder of the Jews, but unlike Western Ukraine, where Ukrainians were involved in murdering Jews from the first days of the German occupation, in the Kharkiv region their involvement began mainly in later 1942. The evidence indicates that these policemen participated in the murder of the Jews largely out of conformist rather than ideological motivations. A steady income was another significant motivating factor for many of these policemen.

Stefan Klemp demonstrates clearly that German policemen who served as guards on deportation trains from Italy to Auschwitz were witnesses to the murder of the Jews and were well aware of the fate of the people in the cattle cars whom they accompanied from northern Italy. Moreover, the deportation escort job was highly desirable among the policemen because it usually gave them a few days home leave in Germany after the deportation run was completed. In this regard, both Radchenko and Klemp engage in the discussion regarding the perpetrators’ motivations, and their findings give us much food for thought. What emerges from their research is that a steady income or a few days of furlough were sufficient motivation to willingly play an active role in genocide.

The current volume also includes three additional articles which examine the local attitudes toward Jews: Joanna Tokarska-Bakir’s anthropological analysis of the July 4, 1946 Kielce pogrom; Samuel Kassow’s review of three books on rural Polish attitudes toward Jews; and Sanford Gutman’s review of two books on daily life in Vichy. Randolph Braham (comparative analysis of German-allied countries), Laurent Joly (critical review of Alain Michel’s book on Vichy), and Omer Bartov (analysis of Peter Longerich’s biography of Heinrich Himmler) analyze the motivations of governments and decision-makers in their policies toward Jews. Lastly, Joel Zisenwine shows that the Allies’ late, limited knowledge of the gas chambers derived from factors that contributed to limiting their responses to the murder of the Jews; and Gershon Greenberg (review article of Esther Farbstein’s The Forgotten Memoirs) opens a window onto personal survivor accounts of ultra-Orthodox rabbis.

- From the introduction of Yad Vashem Studies 41:1 (2013) edited by Dr. David Silberklang

This issue is dedicated to the memory of the journal’s past editor (1968-1983), Livia Rothkirchen, who passed away as this issue was completed and opens with Gila Fatran’s article on her contribution to the field.

Yad Vashem Studies, volume 41, no. 1, with all of the complete articles, is available for purchase.