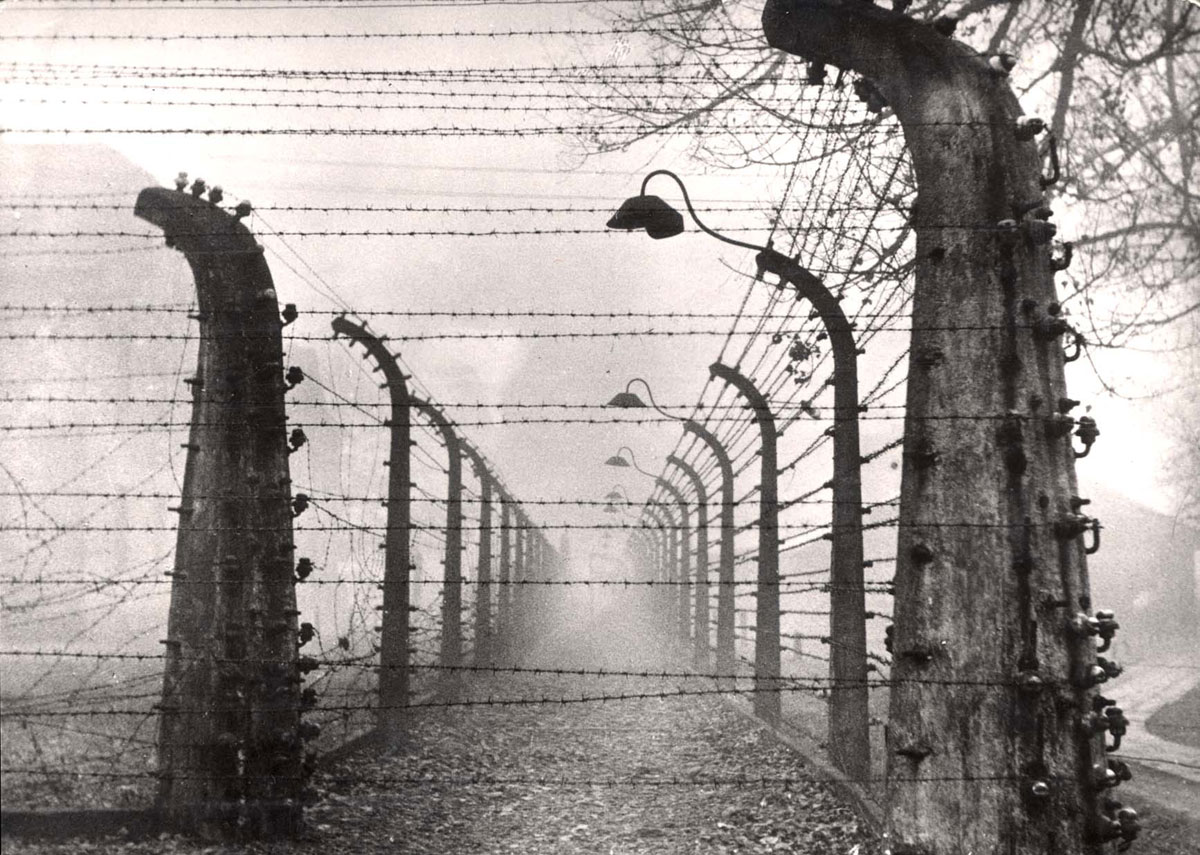

Auschwitz, Poland, postwar, barbed wire fences in the camp

On January 27th the world marks International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which was adopted by the United Nations in November 2005. In many venues Holocaust Remembrance Day has become a day not only to commemorate the Holocaust, the systematic murder of some six million innocent Jews by the Nazis and their partners during World War II, but a day to mark the tragedies of others who were victimized during the war, as well as victims of other instances of genocide in the 20th and 21st centuries. Three key concepts often accompany the public discourse that is bound up in these commemorations: racism, genocide and human rights. Somewhat perplexingly, although the other events that are marked are clearly associated in the public mind with these concepts, far too frequently the Holocaust is not. Yet the Holocaust must be tightly bound up in any serious discussion of racism, genocide and human rights.

In common parlance, racism is generally thought of as the discrimination of one group by another owing to their physical characteristics, especially their skin color. Since the Holocaust occurred primarily in Europe, among a populace that at the time predominantly shared the same color of skin, people often gloss over the fact that the ideological underpinnings that wrought the Holocaust were racist. The Nazis, like many of their contemporaries in the West, considered the different people of Europe separate, albeit sometimes closely related, races. It was common in the language of the time to speak of a Germanic race as opposed to a British or French race, expressions which one rarely hears today, if at all. The Jews were also commonly considered a race, (although if race is a matter of physical type, one must do no more than spend a few hours in Israel to see that there are Jews of all types and hues). The Nazis considered the so-called Germanic race to be the master race and others to be inferior to it. As to the Jews, they deemed them not only the antithesis of the Germans, but inherently dangerous to the rest of mankind. This false and hateful perception is not the only reason for the Holocaust. Nevertheless, it lies at the nucleus of any thoughtful explanation as to why it took place. If the Nazis were anything, they were certainly racists, and blameless Jews were their foremost victims.

Genocide is a crime that was first articulated as an idea at the end of World War II by Raphael Lemkin, a jurist and a Jew, who sought to codify the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis against the Jews. Genocide, as he defined it, has two components. The first is the attempt to completely, physically obliterate a group of people. The second is to engage in acts, including mass murder and the prohibition of culture, that lead to the destruction of a group of people as a group, but not to their total, physical annihilation. Thus, by definition the Holocaust is genocide. But it is a form of genocide that fits the first half of Lemkin' s definition, since the Nazis sought to wipe the Jews off the face of the earth. Other genocides after the Holocaust have much in common with it, but there have yet to have been new attempts by one group to annihilate all the members of another group, everywhere. These genocides are weighted more toward the second half of Lemkin's definition. On December 9, 1948, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, based on Lemkin's formulation, was adopted by the United Nations, making the perpetration of genocide an internationally recognized crime.

On the day after the approval of the Genocide Convention, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Like the Convention, this too was born of the experience of World War II. Although the Jews were not the only people to suffer from the infringement of the rights set out in the 30 articles of the Declaration, (among them the right to life, dignity and personal security), they certainly suffered the ruthless violation of all of them under the Nazis and their partners. Thus, the Holocaust at its core is a blatant instance of the violation of human rights.

The Holocaust is a specific historical event that struck at a particular group of people, but has profound universal implications. It is the story of how the Nazis and their partners murdered Jews simply because they were Jews. It is also the story of how a group of people arbitrarily defined another group as dangerous and sought to murder them all. In 2010 the discussion of racism, genocide and human rights, anchored in the history of the Holocaust, remains not only pertinent, but is crucial to the health of human civilization. Taking the Holocaust out of the discussion is not merely a sin of omission. It is a distortion of history that nourishes those who purvey the kind of hatred that can lead to future genocidal assaults.