We are in Nieśwież, and we hear how, every day, they are killing those in the city, and now it’s our turn – today or tomorrow. We are lying fully clothed with our children, so beloved and talented, and waiting to die.

Excerpt from the last letter of Shalom Mordechai Hishin

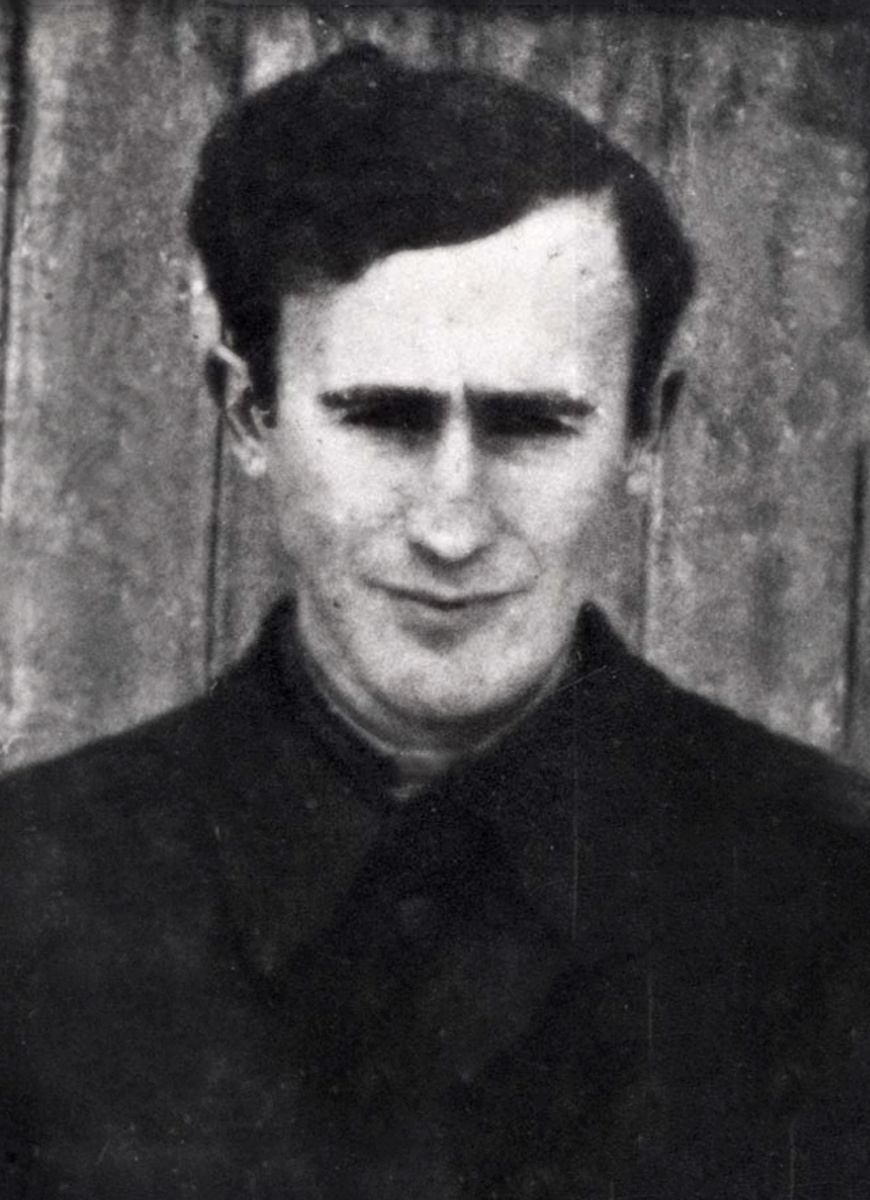

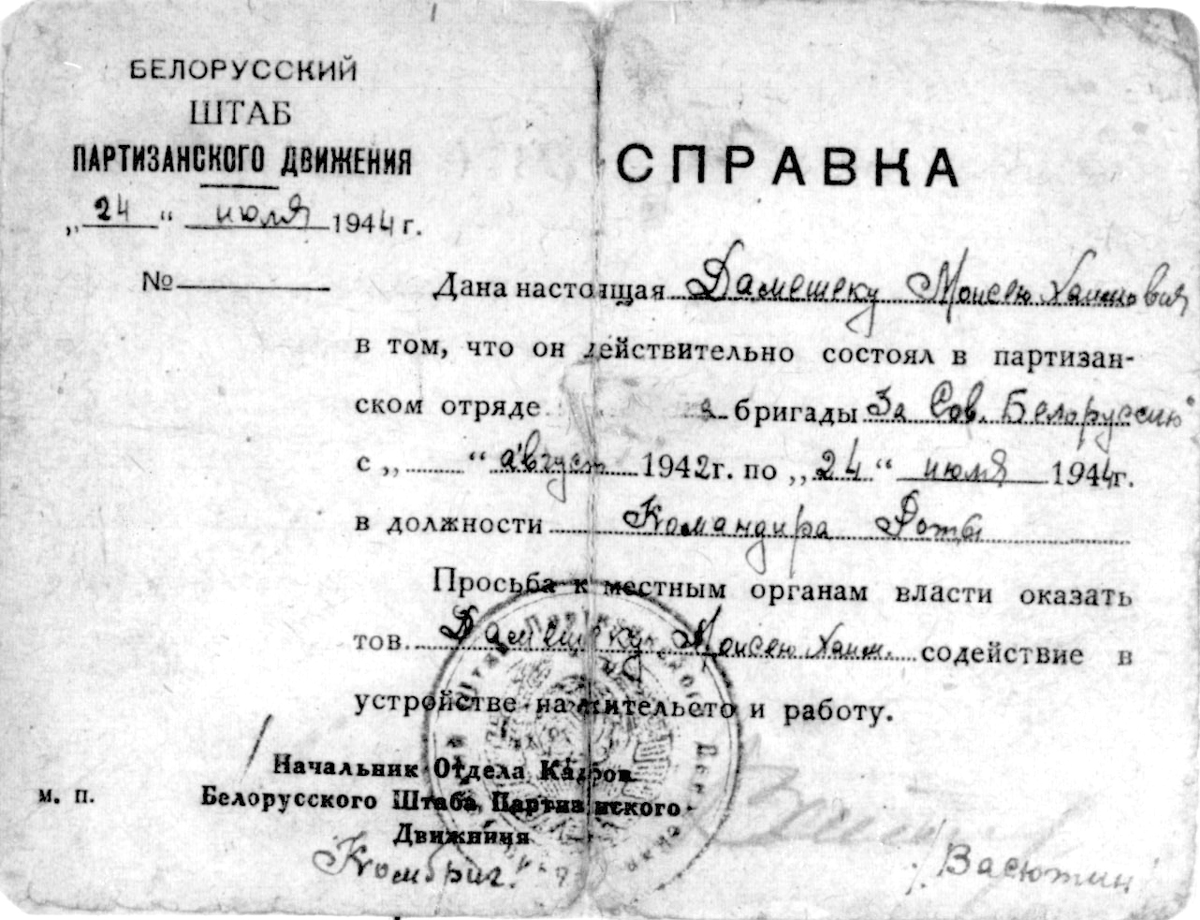

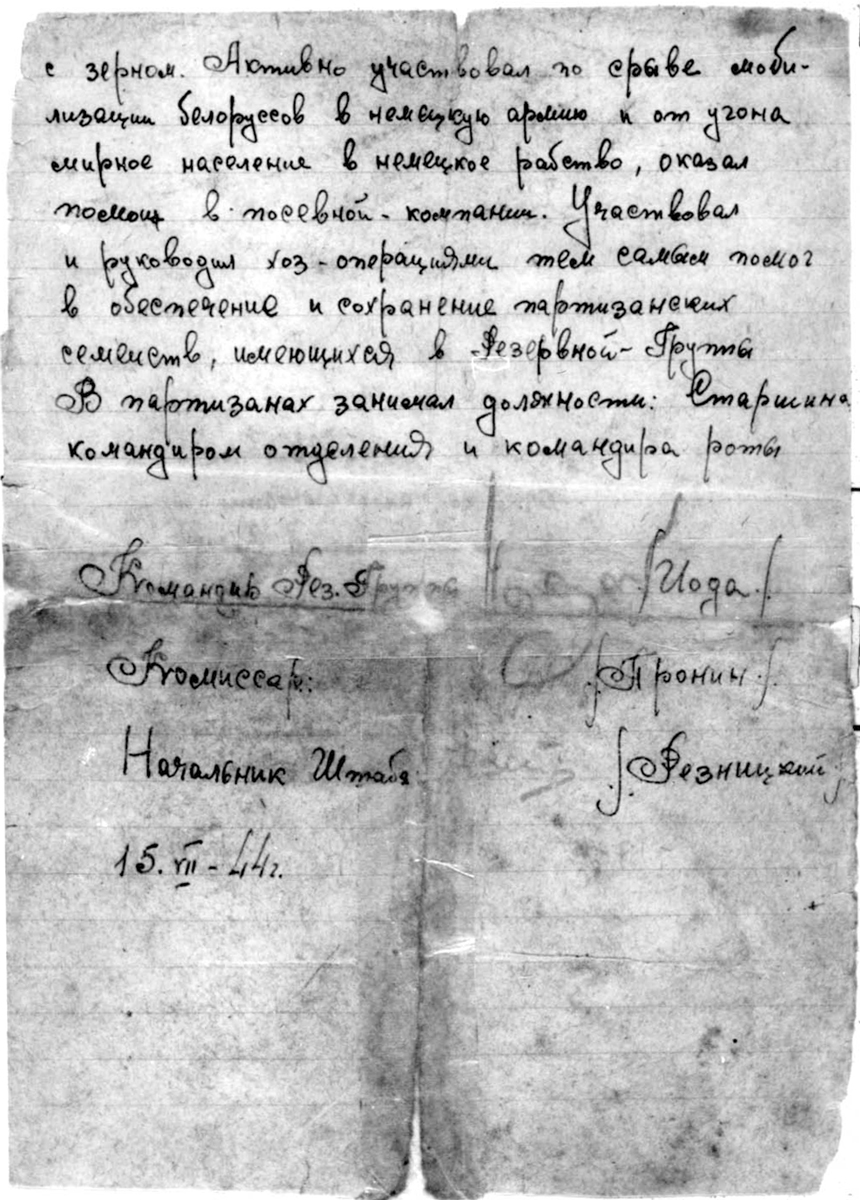

They lived with a group of partisans in the forest from 22 July 1942 until 22 July 1944.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 7636/100

The Establishment of the Ghetto and the Organization of a Resistance Movement

After the murder of some 4,000 of the city’s Jews in October 1941, the 685 workers and their families who were still alive were taken to the high school building, where they stayed overnight. The next day, they were moved to the road where the synagogues were located. The road was fenced in with barbed wire and converted into a ghetto. The families were crowded into old, ramshackle houses, and assigned to hard labor outside the ghetto, or in workhouses within the ghetto. The Judenrat attempted to organize the housing and the work inside the ghetto, and to ensure the orderly distribution of food. There were also Jews in the ghetto assigned to keeping the peace.

In December 1941, young ghetto inmates headed by members of “Hashomer Hatzair” met clandestinely and organized themselves into a resistance group. They started by questioning the authority of the head of the Judenrat, whom they did not trust. The members of the resistance, who included some members of the Judenrat, set up a clandestine school, despite the Germans’ express prohibition, and organized the ghetto workers into a professional union. They made weapons, including knives, axes and nail-studded clubs, and combustion materials to set fire to the houses in the case of an uprising. Two Jewish engineers made phosphoric acid for the manufacture of Molotov cocktails. Two young girls who worked in the German headquarters’ arms storehouse smuggled some bullets and hand grenades into the ghetto, and even a dismantled light machine-gun. Dov Alperowitz smuggled several guns into the ghetto, and the resistance members called on the Jews in the ghetto to dig bunkers and stock up on food.

The First Jewish Uprising in the Ghettos

The first armed uprising to occur in the ghettos took place in Nieśwież (alongside the revolt in nearby Kleck). In general, testimonies reveal that in the region of Nowogrodek, Eastern Poland, the Jewish response was characterized by opposition to the Nazi occupier, and armed resistance.

On 17 July 1942, the Jews in the ghetto heard about the murder of the Jews of Horodziei, a mere 14 km from Nieśwież. On 20 July, Germans and Byelorussians arrived in the ghetto and collected various items that had been delivered to craftsmen for repair. Sensing impending danger, the resistance declared a high alert.

On 21 July, Germans and local policemen surrounded the ghetto, and the Jews were ordered to gather for a selection, but the head of the Judenrat sent a message back to the Germans that the Jews refused to obey the order. The Jews of the ghetto rose up in rebellion, led by members of the resistance, among them Shalom Holavski and Haim Eliyahu Polaczek. In response, the Germans opened fire on the ghetto.

We ran out, my wife and I, to the communal area. There was a sense of impending destruction. You could see that the moment was drawing near. The decision reached a day earlier in the Bet Midrash, “I will die together with the Philistines”, had to be carried out. Not to allow another selection; to set the ghetto alight, to create a commotion – the lucky ones will survive. Not to allow anything. No selection, no looting by the Germans, all the good things that the local population, the Christians, were waiting for. And that’s what happened. In several places in the ghetto, red flames started to swallow up one house after the other. In the area where I was posted, I set fire to the houses. We saw the ghetto in flames, and amidst the burning ghetto, people tried to break through the barbed wire.

The group of Jews inside the "Kalter Shul" [the “Cold Synagogue”] opened fire on the Germans standing outside the ghetto, and a battle began.

Excerpt from the testimony of David Farfel, Yad Vashem Archives

The little ammunition at the disposal of the resistance ran out quickly, and they carried on fighting with their weapons, and set fire to the houses in the ghetto. Most of the Jews in the ghetto were killed in the battle. Some 40 Germans and Lithuanians were killed or wounded.

The fire in the ghetto spread to the houses outside its confines. A small number of Jews managed to hide within the ghetto. Some 25 Jewish fighters escaped to the forests and joined a unit of partisans led by a Soviet Jew from the town of Kopyl, which formed part of a Soviet military division. Some of them reached Jews living in nearby areas and notified them about the mass murder and the uprising. This notification influenced the Jews of Mir in their decision to escape from the ghetto.

The Red Army liberated Nieśwież in July 1944. A few Jews survived in the forests or by hiding in the homes of local farmers. Most of the survivors who returned to Nieśwież left a short time later, moving to other places in Poland. The majority eventually immigrated to Israel.