In October 1939, the Germans announced the creation of a ghetto in Piotrków Trybunalski, and by January 1940 all the Jews of the city had moved into the ghetto area. It may be that the reason for establishing a ghetto at such an early date was that the city had been heavily damaged by bombing, and the Germans wanted to make room for Polish refugees in the city, as well as for Jews who had been expelled from of former Polish territories that had been annexed by the Reich. In addition, it is clear that local German residents of the city (“Volksdeutsche”) wanted to take over whatever Jewish assets were available – apartments, factories and possessions.

The Germans set a number of dates on which Jews were to move into the ghetto confines. When the Jews failed to comply with these dates despite announcements published by the Judenrat, the Germans began forcibly throwing Jews out of their apartments, ordering them to take up residence within the ghetto. Newly vacated Jewish apartments were handed over to non-Jews; at the same time, non-Jews were ordered to leave their apartments in the area designated for the ghetto, and to take up residence on the non-Jewish side of the city. Despite this, until the spring of 1942 the ghetto still housed many Polish residents.

Until April 1942 the Piotrków Trybunalski ghetto remained ‘open’: it was not fenced in, nor was it guarded. The ghetto’s perimeters were marked by signs bearing the word “ghetto”, along with a human skull, but Jews were allowed to leave the ghetto without a license, albeit only during specific hours, and only to a certain part of the city. Many Jews, however, removed their armbands and roamed freely around the city. Several were even granted licenses to travel beyond the city limits. A number of Jewish artisans worked for Poles and Germans, and were paid. Jewish traders and merchants also succeeded in maintaining trade relations with residents - including non-Jews - of other cities, such as Warsaw and Częstochowa.

Many Jews smuggled food and heating materials into the ghetto. Illicit food production also flourished in the ghetto. Trade within the ghetto was brisk, and many Jews plied their trade as merchants, bribing the Polish and German authorities to allow them to continue their underground activities. At times the ghetto was searched, merchandise confiscated, and Jews executed for smuggling, yet these actions did not stop the illegal activities in the ghetto.

Most of the officially-sanctioned work places for Jews lay outside the ghetto. Thousands of Jews, among them many Jewish youths, worked in factories producing glass, wood and alcohol in the railway workshops and in other workplaces. The Judenrat established workshops that employed hundreds of skilled workers in the garment industry; their merchandise was supplied to the German market.

Until October 1940 the Judenrat succeeded in helping a number of Jewish families in the ghetto to emigrate from Poland. At the same time, the number of residents in the ghetto continued to rise steadily, due to an influx of Jewish refugees. While at the beginning of the war the city had held some 10,000 Jews, by April 1942 the number had risen to 18,500. All the Jews now lived within the ghetto, and almost 8,000 of them were refugees. The refugees came primarily from areas in western Poland – Pomerania, Poznan and Lodz – which had been annexed to the German Reich. Additional refugees came from Polish territories that had been annexed to the Soviet Union; these were refugees who had fled when the Soviet Union began deporting Jews to Siberia.

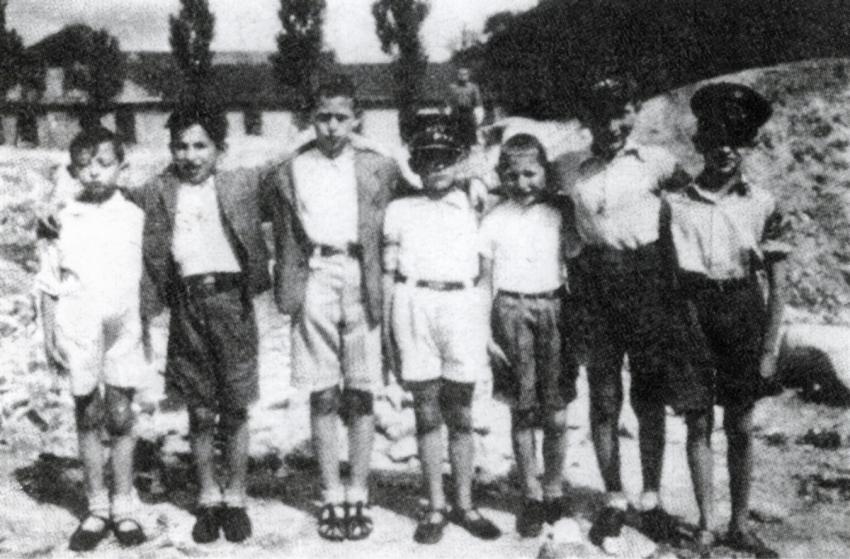

Most of the refugees were utterly destitute; despite the difficult conditions, the Judenrat’s Welfare Department attempted to provide them with aid. They were housed in religious and cultural institutions and also in butcher shops in the market. They received support from the Judenrat in the form of food, clothing and medication. The ghetto had two clinics, a family health center, a pharmacy and a dentist. Some of these institutions operated with the support of the Judenrat, which also distributed small sums of money to the needy. Rabbi Lau and a group of women founded the first soup kitchen, and two more were subsequently established. Later, the ghetto kitchen was supported by the Warsaw branch of the Juedische Soziale Selbsthilfe (the Jewish Social Self-Help foundation, or Żydowska Samopomoc Społeczna in Polish, a Jewish mutual help organization for monetary aid, medical supplies, clothing and food; the organization operated in the Generalgouvernement, its headquarters were based in Krakow). The Welfare Department in the Judenrat established an orphanage and a children’s club supervised by teachers, in which the children were provided with warm meals. A number of orphans were taken into foster care.

Despite these attempts to alleviate the situation, the intense crowding, insanitary conditions and hunger led to outbreaks of epidemics within the ghetto, resulting in a number of deaths. In the winter of 1940-1941, an outbreak of spotted typhus led to the establishment of several temporary hospitals and isolation rooms within the ghetto area. Sixty members of the “Sanitary Police” set aside buildings for isolating patients, disinfected apartments, and even forcibly washed, sterilized and isolated patients so as to forestall the spread of the disease. By spring, the epidemic had been eradicated, but the next winter it broke out again, albeit in a lighter form. The same methods were used to suppress the second outbreak of the epidemic.

Despite the conditions in the ghetto, the various political parties and Jewish youth organizations active in Piotrków Trybunalski before the war continued to function, first and foremost the Bund, but also Hashomer Hatzair (that organized a kibbutz for practical Zionist training in Żarki) as well as Beitar. A number of heders (religious primary schools), schools and yeshivot (Talmudic colleges) also continued to function. In addition the ghetto was home to a number of private teaching groups and small libraries, as well as a drama group. Several “bazaars” were held, and the revenue generated was donated to the orphanage. Jews in the ghetto continued to celebrate the holidays, and did their best to fulfill the various mitzvot (religious commandments); they persisted in these efforts right up to their deportation, at the end of 1942.