Within 50 years the Jewish population of the city had increased fourfold, and by 1902 it had reached 10,000 – more than a half of the total population in the city, despite the fact that this period was marked by famines, epidemics and fires all of which claimed the lives of hundreds of Jews. The increase in the number of Jews was partly due to official edicts that expelled Jews from neighboring cities and villages bordering on the western front of the Russian Empire. Some of the refugees found shelter in Šiauliai, thereby aggravating the already difficult situation in which the city’s Jews found themselves. Housing and work opportunities were particularly bad. Conditions were exacerbated by a heavy tax that the Russian authorities levied against the Jews of Šiauliai.

At the beginning of World War I, Šiauliai was the site of heavy fighting, as a result of which the city’s center was destroyed. Russian Cossacks carried out pogroms against the Jewish population, recruiting young men to dig defense ditches outside the city and expelling nearly all of the remaining Jews to Russia.

From 1919, with the establishment of an independent Lithuanian state, Šiauliai’s importance grew, and it became a provincial capital. Some of the Jews who had been expelled during Russian rule now returned to the city. With the help of their relatives in South Africa and the United States, as well as aid provided by the Joint Distribution Committee, they restored the ruins of their homes and businesses, reestablishing the prayer houses, the yeshiva and some of the batei midrash (study halls). The orphanage was now housed in one of the refurbished study halls. The Jewish hospital was also reopened, as were many charitable foundations and a branch of the OSE (Oeuvre De Secours Au Enfants), a worldwide Jewish health organization.

During this period antisemitic attacks occurred from time to time, as well as incidents that targeted Jewish businesses. The Lithuanian traders’ union came out against purchasing from Jewish businesses; as a result, the livelihood of many Jewish merchants in Šiauliai was damaged. Other non-Jewish residents in the city campaigned against kosher slaughter and signs written in Hebrew letters. On the eve of World War II, there were blood libels in Šiauliai and a number of pogroms were carried out. Some 6,600 Jews were living in Šiauliai before the outbreak of war, about 20% of the city’s total population.

In March 1939, when the Lithuanian city of Memel (Klaipėda) was annexed by Germany, many Jewish refugees from Memel found refuge in Šiauliai. Toward the end of 1939, the Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement, in which Poland was partitioned between Germany and the Soviet Union, resulted in a wave of Jewish refugees to Šiauliai. These included members of Hachshara kibbutzim for practical Zionist training. At the beginning of 1940 these Zionist pioneers organized a new Hachshara kibbutz for 120 refugees who were members of the Hechalutz movement. When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union in June 1940, Jewish political activity in Šiauliai ground to a halt. The youth movements were disbanded and the kibbutz was dissolved. Institutions for Jewish education, including the gymnasium, were closed or converted into communist educational institutions. Jewish private businesses, as well as many Jewish houses, were nationalized. In June of 1941 many Jews were exiled to Siberia and other parts of the Soviet Union after having been declared 'unreliable elements'; among those exiled were many Zionists.

Trade and professions

During the nineteenth century Šiauliai was the urban and commercial center of the entire region. The city’s economy was based on trade in agricultural products, which were shipped to the port cities of Riga and Liepāja. Most of the city’s Jews were smalltime merchants, peddlers and wagon drivers. Some owned and operated inns, stables and public houses. At the end of the nineteenth century, trade in hard liquor, which had previously been free, became a monopoly of the Russian government. As a result, many Jews lost their source of income, but the community stood its ground, as Jews from Šiauliai succeeded in establishing large factories for leather tanning, one of which employed thousands of workers. Other important factories were established too, including tobacco and cigarette factories, soap factories, flax-processing factories, and factories for metal casting, for beer, for chocolate and for sweets. At this time the city’s Jews also established large trade emporiums which specialized in the export of flax, animal hides and grains.

At the end of the nineteenth century a Jewish hospital with 12 beds was established. A few years later, the hospital was moved into a new two-story building that had an operating theater, a clinic and a pharmacy. The Bikur Cholim and Leinat Tzedek charitable associations supported the hospital financially, providing medical supplies and aid for impoverished patients. Meanwhile, the former hospital building was converted into a senior citizens' home. Šiauliai also had a building owned by the Hachnasat Orchim (hospitality) association as well as an orphanage, and a number of organizations that provided interest-free loans for the needy. Finally, Šiauliai operated an organization known as Maachal Kasher (Kosher Food), which provided kosher meals for Jewish soldiers in the Russian Army stationed in the city.

During the interwar period, most of the Jews made their living from industry and trade, and several hundred Jews worked as manual laborers, as clerks and in the liberal professions. There were over 200 small factories in the city, of which more than half were owned by Jews. 200 Jewish craftsmen were unionized in a professional labor union that organized a loan fund and provided the union members with medical care. A Jewish industrial bank and a society for mutual credit played an important role in the financial life of the city’s Jews. The Frenkel family’s leather goods factories employed hundreds of Jews. Jewish tradesmen and merchants worked in export businesses on the Baltic Sea. The city was home to private banks owned by Jews, as well as to Jewish associations for credit and loans.

Politics

Most of the Jews in Šiauliai had Zionist sympathies. The city was home to a large number of Zionist parties, including the Revisionists, Hibat Zion, and Mizrahi. The Zionists of Šiauliai founded the Zamir organization, which held literary and musical soirees. Yitzhak Tzvi Shapira, born in Šiauliai, was among the founding members of the city of Petah Tikva. His son, Abraham Shapira, was head of the Jewish Watchmen’s organization (Hashomrim) in Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine), and one of the leaders of the Hagana. Graduates of the Šiauliai Zionist movements were among the founding members of the cities of Kfar Saba and Rehovot.

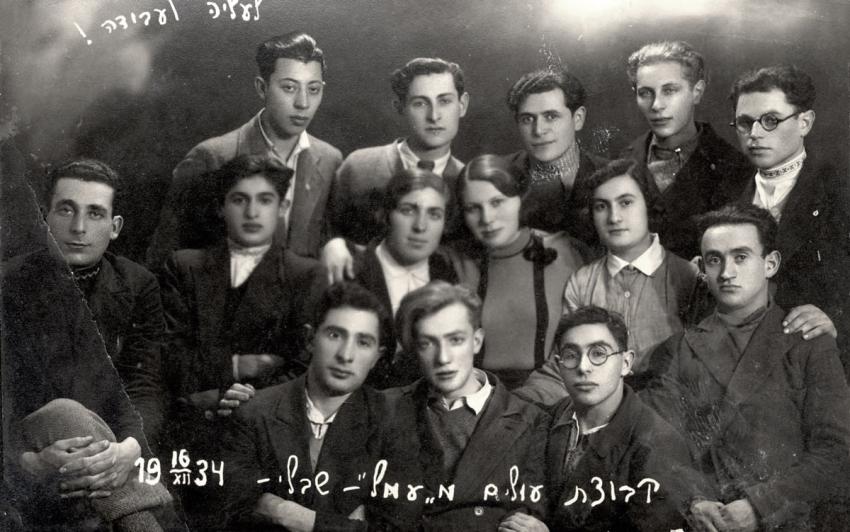

There were many youth groups affiliated with the Zionist parties, among them Hechalutz, Hashomer Hatzair, Beitar (from 1929), Hapoel Hamizrahi, Gordonia, Zionist Youth and Bnei Akiva. Šiauliai was also home to a number of kibbutzim for practical Zionist training. The Hechalutz movement operated a woodworking factory and a confectionery factory. In the years 1920-1921 a group of Hechalutz members immigrated to Eretz Israel.

Šiauliai also had branches of the Zionist sports organizations, Maccabi and Hapoel. The Bund party was active in Šiauliai until World War I, and was supported by hundreds of the city’s Jewish laborers and craftsmen. A branch of Agudat Yisrael was also active in Šiauliai, and there were a number of Jews who belonged to the Communist Party.

Education, culture, and religion

Jewish children studied in the traditional heder (religious primary school), but gradually more institutions for general education sprang up, among them Jewish associations, Russian gymnasiums, Jewish schools for professional training, private Jewish schools and even government-sponsored schools for Jews, one of which was established by the renowned Jewish poet, Judah Leib Gordon. In addition, a number of adult education classes were held.

Important figures in Jewish nineteenth century life who were born in Šiauliai included: writers Joseph Lazar Epstein and Jacob Tzvi Sobel; rabbi and educator Abraham Baruch Rhine; Tuvia Danzig – later a professor of mathematics at the Columbia and John Hopkins universities; Victor Brenner – a sculptor, engraver and medalist renowned for designing the United States Lincoln Cent; and the Zionist philanthropist Raphael-Shlomo Gutz.

Jewish youth studied in a number of Jewish and governmental institutions in Šiauliai. These included: a religious Hebrew school that held 400 students; a number of Hebrew schools belonging to the Tarbut network; a Hebrew gymnasium founded in 1920; a religious gymnasium belonging to the Yavne network; a Yiddish school with 300 students; and two kindergartens – a Hebrew kindergarten and a Yiddish kindergarten. The Hebrew gymnasium had a preparatory school as well, and held after-school enrichment classes, becoming a focal point for Zionist activities. Many of the school’s students immigrated to Eretz Israel, including many to kibbutzim. However, schooling in Hebrew was gradually curtailed by the Lithuanian authorities, and the Hebrew gymnasium was forced to comply. Each of the various Jewish schools in Šiauliai contained its own library; the city also hosted two larger libraries, one Yiddish and the other, Hebrew. From time to time, vocational Jewish schools were also opened in the city.

Many Jews were regular visitors to the city’s government-run theater, and occasionally Jewish theater troupes from Kovno (Kaunas) would visit Šiauliai. A Yiddish paper – Die Zeit (The Time) – was published in the city. In addition, most of the members of the city’s fire brigade were Jewish. The “Union of Jewish Fighters who Fought in the Lithuanian War of Independence” had a chapter in Šiauliai, which operated a club and a reading room; these rooms were used for lectures and as a regular meeting place for the Jewish drama club.

Šiauliai was home to a yeshiva (Talmudic college), a large talmud torah (religious school), a beit midrash (study hall ) and a modern heder (religious primary school) for poor children whose families had difficulty paying for religious education. The traditional heders no longer existed. In addition there were a number of kloyzim (prayer and study houses). Workers practicing different trades organized their own kloyzim: the grocers, the traders, the shoemakers, the tailors, the wagon drivers, the butchers and the undertakers. Other kloyzim were created on a geographical basis, with each neighborhood establishing its own kloyz. This normally occurred as a result of local initiative with the support of well-to-do Jews and the religious community. The majority of the community was affiliated with the Mitnagdim (the stream of Judaism opposed to the Hasidic movement) although there were more than one hundred Hasidic Jews in the city. In the summer of 1915 the Germans captured the city. The retreating Russian Army burned the city center, which had been home to most of the city’s Jews. The magnificent synagogue, built in 1749, was destroyed in the fire, as was the new yeshiva building.

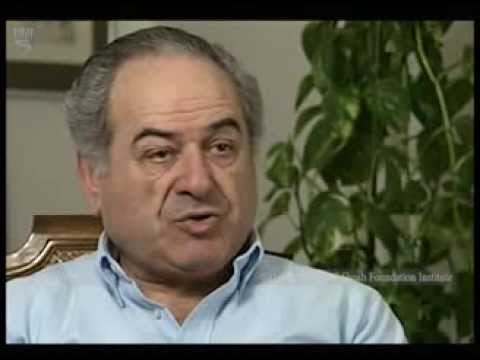

Famous members of Šiauliai during this time include: lawyer Dov Shilansky, one of the Etzel commanders in Europe and later Speaker of the Israeli Knesset; journalist and writer Ester Kall; educator David Pur; and professor of history David Golan.