In November 1942 the Germans established a “restored ghetto” in two different parts of Szydłowiec; both ghetto areas were surrounded by barbed wire. The German authorities ordered Jews who had survived the deportations to settle within the new ghettos, on threat of death. Within a short period of time some 5,000 Jews were gathered in the new ghetto. These were Jews who remained from the Szydłowiec community as well as deportees from other towns; a fifth of the new ghetto’s population – some 1,000 Jews – were deportees from Radom. The ghetto’s houses had been heavily damaged in the looting, and most of them had no roofs, windows or doors. For this reason the ghetto’s residents were housed in the leather tanning factories. Members of the Gestapo, along with other Germans and the Polish policemen, terrorized the ghetto Jews, committing murder on a daily basis on the slightest provocation. Motel Eisenberg wrote: “It is clear that this situation cannot last for very long; the remaining Jews are being concentrated [here] in order to be destroyed.”

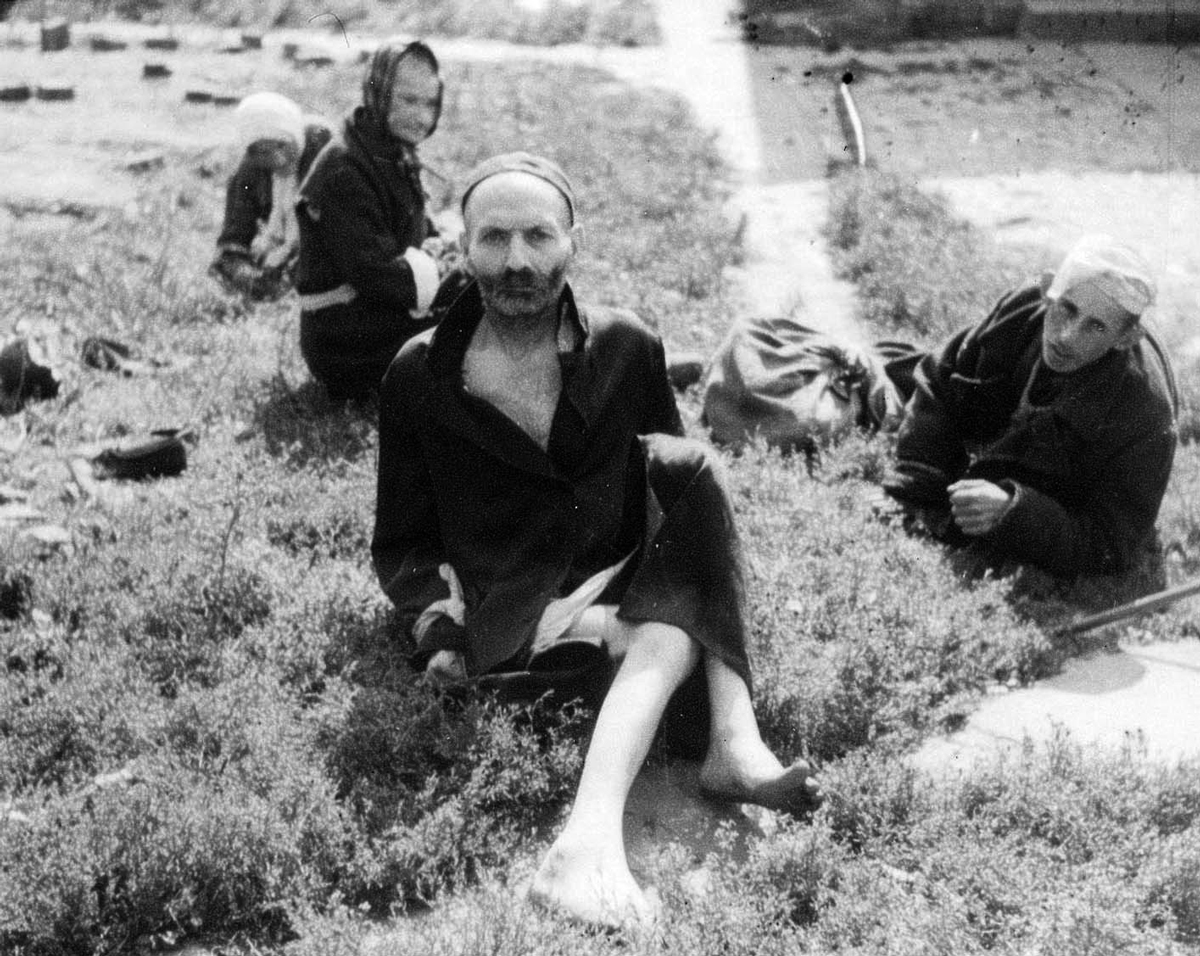

Photographed by an anonymous German photographer in late 1942 or early 1943.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives FA76/103

The Germans appointed a new Judenrat, headed by Shmuel Weisbrot. Eisenberg described the new period in the ghetto:

“Life in the ghetto has succeeded in stabilizing itself. A new Judenrat has been appointed, as well as a Jewish police force. Jewish doctors administer medical treatment. Commerce is developing. The Jews bustle about the neighboring villages in an attempt to acquire a bare minimum of food. The Jews have established restaurants where one can find warm, if meager, meals. Polish people enter the ghetto, bringing goods with them and purchasing clothes, undergarments, watches and jewelry. Polish villagers from the surroundings also arrive, offering to hide Jews for a decent price.”

However this respite did not last long. Lack of food and water, together with the crowded living conditions led to the outbreak of a typhus epidemic, in which many of the ghetto’s Jews died. Forced laborers who succeeded in escaping from the Hasag camp found the conditions in the ghetto so bad that they preferred to return to the camp. A few days before the liquidation of the ghetto hundreds of exhausted prisoners from Hasag arrived in the ghetto, and 1,000 young people from the ghetto were sent to the camp to replace them.

On 8 January 1943, the Szydłowiec ghetto was surrounded, and on 13 January SS men entered the ghetto. Some 80 Jews were murdered in the ghetto itself and en route to the train station. The SS men shot children and hospital patients. Ukrainians set upon the deportees, robbing them of their last belongings. Some 5,000 of the ghetto Jews were put on deportation trains and sent to their death in Treblinka. The Jewish community of Szydłowiec ceased to exist.

Hiding with a Polish farmer near Szydłowiec, Motel Eisenberg heard an account of the ghetto’s liquidation:

“We sit as though after the funeral of those closest to us. […] Several families, among them the family of Pinchas Steinman, decide to resist the deportation and declared that they would not board the train wagons. They were all shot. Before that, however, they succeeded in tearing up all their money and throwing the pieces into the field.”

Eisenberg spent more than two years in the cellar of the Polish farmer, who hid him in return for payment. He wrote the following lines regarding the liberation:

“On the night of the 14th of January 1945, the Germans left the house, and in the evening our farmer enters the cellar bearing with him the wonderful – almost incredible – news: the Red Army had taken Szydłowiec. We crawl forth from our grave, downtrodden but happy to have survived. […] Before day break, in the dark, we walk down a side road which leads to Szydłowiec. I drag my feet with difficulty, because after many long months I have grown unaccustomed to moving them. We enter the town. It is hard to believe that until not very long ago thousands of Jews used to live here.”

After the Holocaust

After the Holocaust 300 Jews gathered in Szydłowiec. Most of them were survivors of the forced labor camps, as well as a few who had been hidden by Polish citizens. These Jews abandoned the town in light of the waves of antisemitism that swept Poland during the first months after the war’s end.

Few records, letters or diaries remain from the Jewish community in Szydłowiec. The magnificent past of the Jewish community is reflected in the Jewish cemetery, whose ancient tombstones have survived. Today, this cemetery is one of the most beautiful Jewish cemeteries in Poland; the Polish government has declared it a historical site and maintains its upkeep.

The Szydłowiec Photo Album

In the early 1960s Yad Vashem received an original photo album, containing 105 photographs with handwritten captions in German. It seems to have been the private album of a German policeman who, using his own camera, documented the residents of Szydłowiec during World War II: the refugees who gathered there, the town's streets, its synagogues and its Jewish cemetery. The anonymous photographer wandered the streets of Szydłowiec, apparently accompanied by a member of the Judenrat, who appears in two of the photographs. The photographer did not desist from documenting the deportation of the Jews, and captured images of the murders that took place in the town’s streets en route to the deportation, as well as the plunder of Jewish possessions by Poles and Germans immediately afterwards.