On 23 September 1942, the German auxiliary units – Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Polish policemen together with the local firefighters, under the command of SS officers – surrounded the ghetto. The residents of the ghetto were concentrated at various points within its area. The patients of the Jewish hospital, located in the synagogue, were among the first to be murdered. Other Jews were shot down in the street as they were being marched to the collection points. Some 10,000 Jews were marched to the train station, four kilometers from the town. During this march many of those who tried to escape or could not keep up were shot.

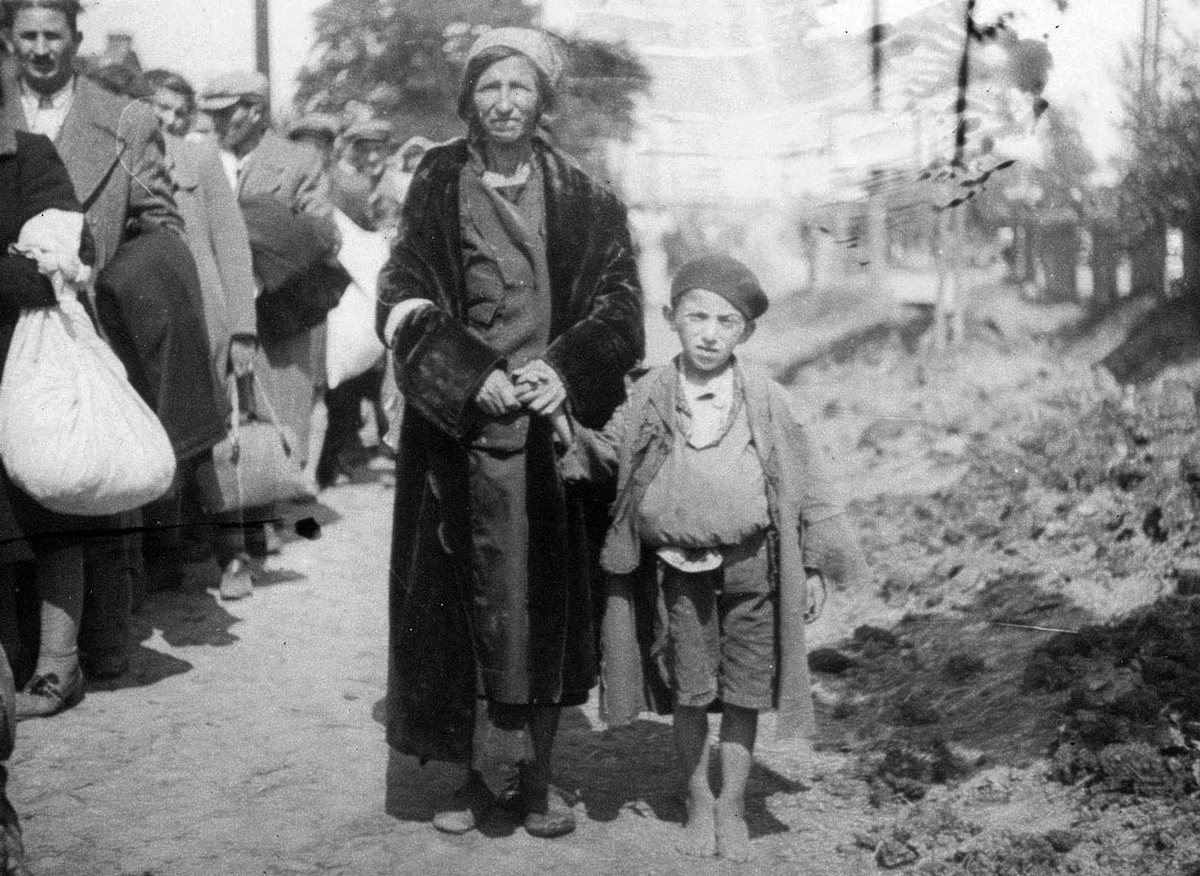

Photographed by an anonymous German photographer in late 1942 or early 1943.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 76/68

The survivors of the march were deported by train to the extermination camp of Treblinka. Close to another 5,000 people were concentrated in an abandoned castle on the outskirts of town. Among those imprisoned there was the Wald family. Yomek Wald (who later changed his name to Benjamin Yaari) described his escape after the war:

“Father collected all the watches and rings we had on our hands, the women’s jewelry as well. In a few minutes he would drop all the jewelry from the tower. The Ukrainians, he reasoned, would be busy collecting the jewelry – and we would take advantage of this diversion to jump. The land on the other side of the castle walls was a marsh. It was quite a high drop, but Father reasoned that the landing would not be too hard and that we should try to escape. And that was how it happened. Father jumped, and after him one or two more. Then it was the turn of one of our acquaintances… A tall fellow, a real tough guy… Standing on the wall he was suddenly gripped by fear, he began to tremble and could not jump… Mother was standing in line behind him with my brother, and they were next in line to jump. She addressed this fellow, asking him why he was not jumping. 'I am afraid,' he replied, 'you jump instead.' And I heard her voice reply, 'I am also afraid.' She grabbed me and said: 'Jump!' I think I may have argued with her, telling her to jump first, but then I heard Father’s voice from a distance, shouting 'Yomek, Yomek!' – He could see that no one was jumping anymore. All around bullets were being fired at those who were running toward the wall in the Ukrainian [sector]. I recall that Mother pushed me, and finally I jumped. Then I picked myself off the ground and ran in the direction in which Father had escaped. After some time I found myself in a small thicket, standing next to Father and a number of other people. We drew away. The shooting ceased.”

For two days the Jews were held in the castle, and then they were deported to Treblinka. Among them were Benjamin Yaari’s mother and brothers, as well as some 100 Jews for whose release a ransom had been paid. 600 additional Jews who had been caught hiding, were also murdered.

After the deportation, hundreds of Jews began to leave their hiding places. “Who would have thought that so many Jews had dared to violate the German order [to evacuate the area],” wrote Isaac Milstein, “it was a great revolt.” Some 500 of the Jews who left their hiding places, among them small children, were murdered in cold blood. A small number of Jews who had been hidden managed to escape Szydłowiec, but some 600 remained in the town, 150 of whom were members of the Order Police, and the remainder, forced laborers. In October 1942 these Jews were transferred to the Skarżysko ghetto, from where some were sent to the Skarżysko-Kamienna forced labor camp; the rest were deported to Treblinka.

During the following two months some seventy Jews remained in Szydłowiec as forced laborers. Their primary job was to bury the bodies of the hundreds of Jews murdered during the deportation, which remained strewn in the houses, streets and outskirts of the town; in addition they collected the personal effects of the deportees. “I stand with my broom in the middle of the street, right next to our house, on Radomska Street 97,” wrote Isaac Milstein. “I want to enter, but cannot. Standing there, tears burst from my eyes as though they were fountains. This is where my crib stood. This is where I knew happiness with my parents and my dearly beloved brothers and sisters.” In November 1942, Milstein was transferred along with the other Jewish forced laborers to the Hasag camp in Skarżysko.