Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in early September 1939, the Germans bombed the town of Szydłowiec and its surroundings. The presence of Polish military forces in the vicinity turned the town into a battleground, and many of the Jews escaped to the nearby villages. On 6 September the Polish Army withdrew from the town and its environs, and locals took advantage of the chaos to loot the property of the Jews of Szydłowiec.

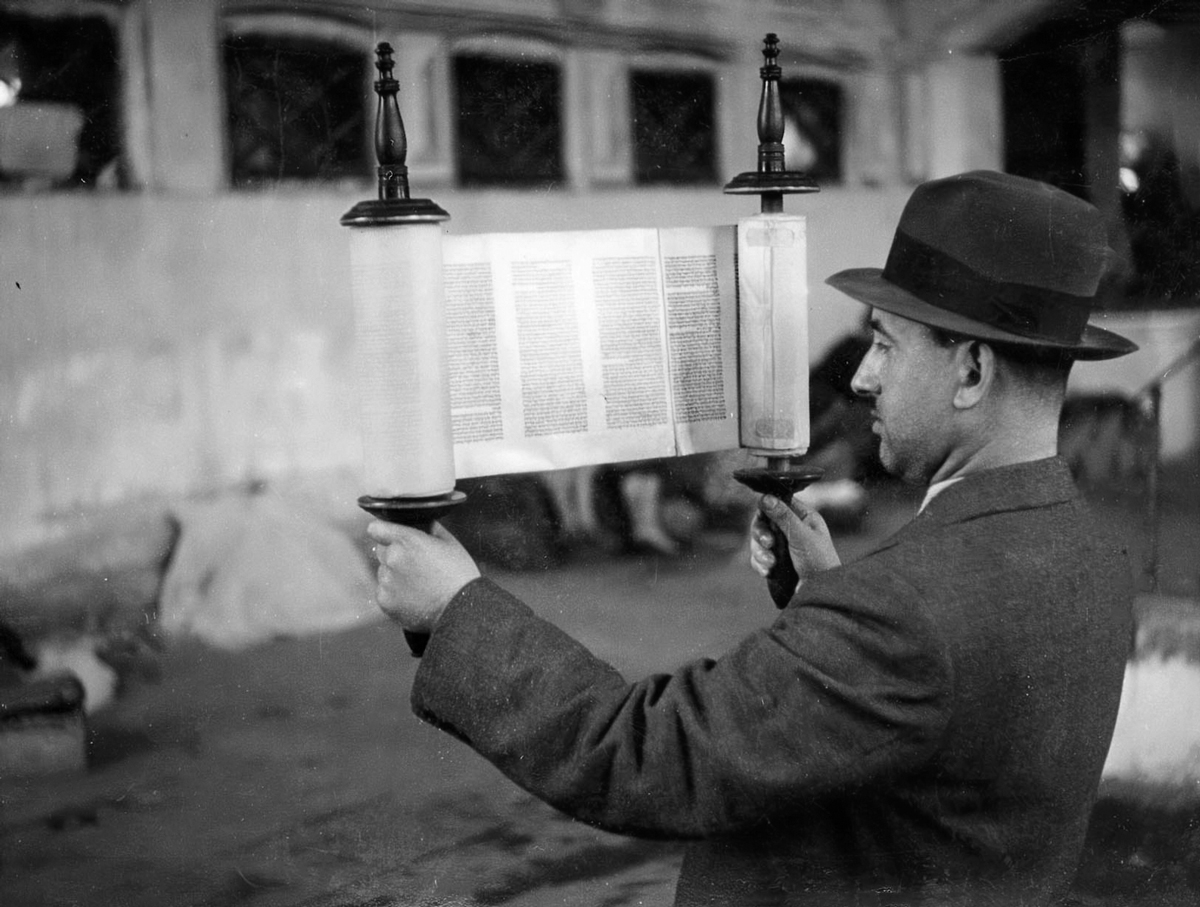

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 76/8

On 9 September the Germans occupied the town, and began abusing Jews and seizing them for forced labor. “Everyday new orders are received,” Isaac Milstein, a resident of the town, wrote in his diary. “The houses of many Jews have been cut off from the electricity. All fur products in Jewish possession have been confiscated. We were ordered to shave off our beards. Kosher slaughter has been banned by law. Non-compliance with the orders means risking the death penalty.”

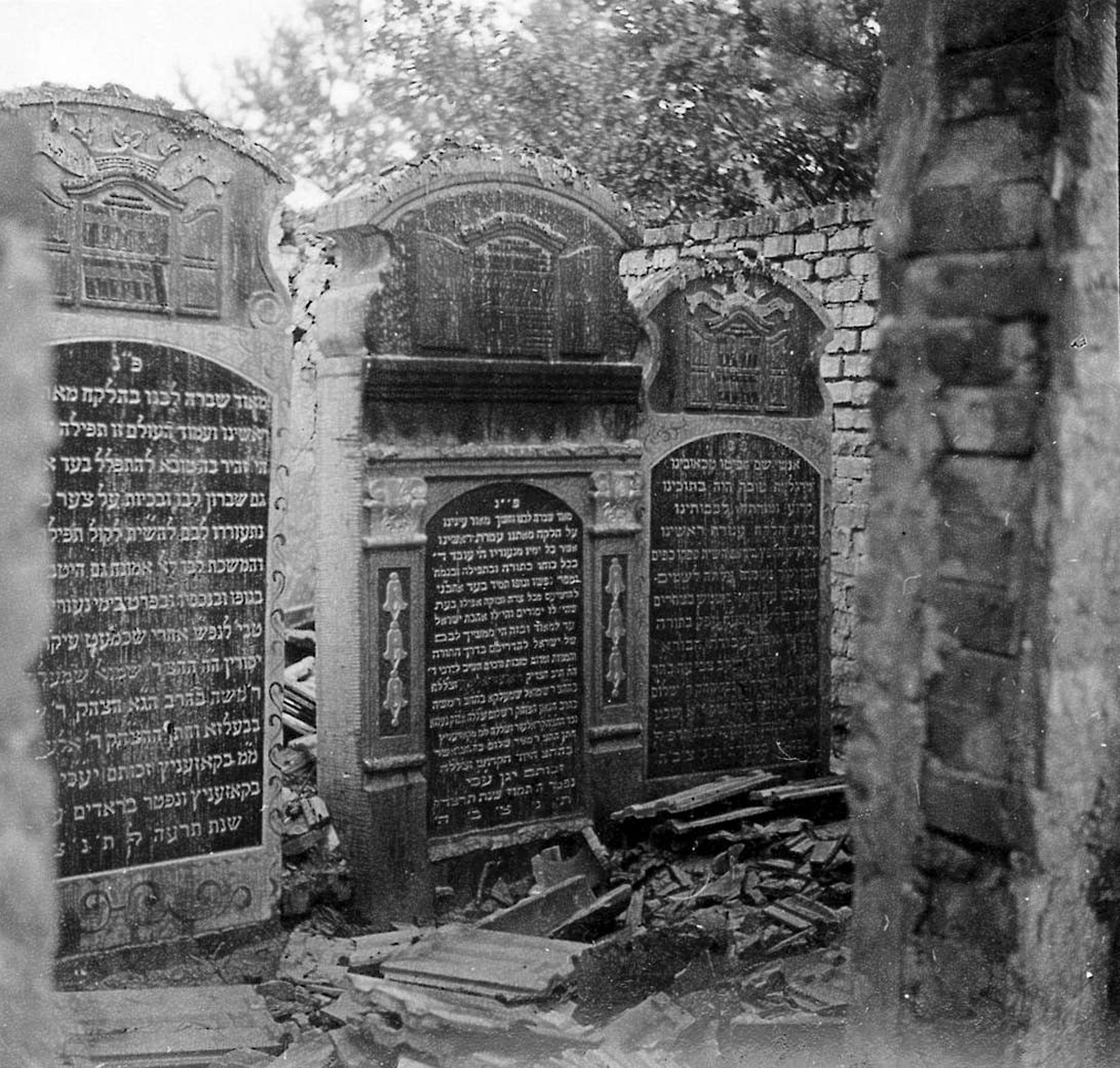

On 23 September 1939, Yom Kippur, one of the town’s synagogues was set on fire. A Judenrat was established in Szydłowiec immediately following its occupation by the Germans, and from the first months Jews were made to wear armbands marking them out in the public sphere. They were forbidden from holding religious ceremonies in public, and were made to pay a high monetary tax as a form of “ransom”. When the Judenrat failed to raise the required sum, the Germans imprisoned 23 of the most prominent Jews in the town, among them the chairman of the Judenrat, and murdered them in the Jewish cemetery.

Following this, a new chairman was appointed to lead the Judenrat – Abraham Redlich, a Beitar activist. The Germans established other “Jewish” institutions aside from the Judenrat, most notably a Jewish employment office and a Jewish Order Police. The latter was placed under the command of a Jewish refugee from Krakow by the name of Ostrowicz. The synagogues and stiebelach were converted into living quarters for Jews who had taken refuge in Szydłowiec or been deported there.

In March 1940 all schooling for Jewish children in Szydłowiec was canceled, and the Germans imposed new restrictions on the Jews, including a curfew during the evening and the night. From time to time Jews, primarly young men, were kidnapped and put to work as forced laborers in occasional construction projects. After some time, the Judenrat agreed to supply the Germans with regular quotas of forced laborers, thereby temporarily putting a stop to the abductions. In August 1940, the SS deported more than one thousand Jewish men from Szydłowiec to labor camps in Wolanow, Janiszow and Jozefow.

Members of the Judenrat traveled by train to Radom in order to bribe officials and their relatives with money and gifts. Avraham Finkler, the secretary of the Judenrat, and the only one of its members to survive the Holocaust, testified that he regularly sent money and articles of value to the regional governor’s mistress, who intervened on behalf of the Jews of Szydłowiec. Redlich and Finkler even succeeded in retrieving 400 forced laborers who had been sent to the Janiszow forced labor camp. One of the Jews liberated as a result of these efforts, Isaac Milstein, wrote:

“On 11 November 1940, something happened that was beyond our very dreams. We awoke, as always, on our filthy bed rags, laid out over the bare planks, and went to the roll-call square. We saw that all other groups were being led to work, except for the men of Szydłowiec… A terrifying thought passed through our minds: If we are not being taken to work, perhaps we are being collected to be sent to a death camp? … The sudden release and the drive home intoxicated us with a joy that is difficult to describe. When we arrived at the town hall, our beloved parents, along with many of our closest friends, were waiting for us. We hugged and kissed them, and together we cried, weeping tears of joy.”

At this time, the prevailing German policy sought to keep Jewish merchants, industrialists and craftsmen in the Radom district alive, in order to strengthen German war production. The region also included Szydłowiec, and it is possible that these considerations were also part of the reason the Szydłowiec ghetto was built at such a late date.

At the end of 1941 an edict was issued, according to which from January 1942 most of the town was to be designated as a ghetto. The Szydłowiec ghetto was unfenced, and living conditions there were somewhat better than in other ghettos in the area; nonetheless, Jews were forbidden to leave the ghetto, and hunger, fear and deprivation were prevalent. Many refugees from nearby towns crowded into the Szydłowiec ghetto, and the number of inhabitants soared to over 10,000. Some 40% of the ghetto’s residents were refugees, and many of them took up residence in the synagogue, where their sanitary conditions were maintained by the Judenrat workers. In an attempt to care for the refugees, the Judenrat established soup kitchens where between 1,000 and 1,800 meals a day were distributed.

Refugees continued pouring into the town, and at the beginning of 1942 the number of Jews in Szydłowiec had reached approximately 12,000. Polish citizens frequented the ghetto in order to steal goods and denounce Jews to the Gestapo, murdering those Jews who opposed them. Members of the German military, the police, the administrative personnel and the "ethnic Germans" (Volksdeutsche) also frequented the ghetto to commit robberies. Faced with a shortage of basic goods, Jews attempted to escape from the ghetto and smuggle in food and raw materials. Many young men and women caught smuggling were murdered.

During 1942, the leaders of the Judenrat sought to increase the ghetto’s production in service of the German war effort, hoping thereby to forestall the seizure of local Jews for forced labor. The Judenrat’s main focus was on the workshops and small factories for leather goods. Out of fear of the kidnappings, many Jews created hiding places for themselves and their friends and families. Later on, these hiding places would serve the Jews of Szydłowiec in their attempts to evade the deportations to Treblinka.

In the summer of 1942 rumors of the mass deportation and extermination that had befallen neighboring communities reached the Szydłowiec ghetto. News of the deportations from Warsaw arrived just as thousands of Jews from villages in the vicinity of Szydłowiec were being deported. At this point the number of Jews in Szydłowiec had reached 15,000. Motel Eisenberg, a Szydłowiec resident described the situation:

“The pressure and the anxiety grow by the day. Our environment regards us with dark looks, waiting impatiently for our final day. We hear the sad news of the deportation of Jewish settlements both near and far. We sense that the fatal hour for our community of Szydłowiec is at hand. The Jews are in despair, frightened, lost. People are liquidating their apartments, their houses. They are selling everything which can be sold. They hand over their undergarments, their clothes, their valuables to Polish acquaintances, hoping to be saved. People are sewing knapsacks and packing them with vital necessities – they are preparing…

Each of us has his own thoughts about what should be done at present. One volunteers for the forced labor camps; another believes the armament factories are a safer work place. Some build hiding places, while others approach their acquaintances in the villages, asking for a place to hide. But the majority of the Jews remain passive, waiting with their families for whatever will come.”

At the beginning of September 1942, fifty Jewish men were deported to the Hasag forced labor camp in Skarzysko-Kamienna. This saved them from the mass deportation from the Szydłowiec ghetto, which was to begin two weeks later. Having heard rumors of an upcoming deportation, other Jews from the Szydłowiec ghetto attempted to enlist in the forced labor camps, trying to save themselves by becoming “vital to the German war effort”.