During the 17th and 18th centuries, Jewish patients visiting the Wiesbaden springs were a major source of income for the local Jews. In part, this was because Jews were forbidden from entering the Christian bath houses. Jews were also forbidden from visiting public gardens and attending certain cultural activities.

At the beginning of the 18th century Wiesbaden had one synagogue, which in 1732 was repositioned on the roof of a bath house. In the mid-17th century a Jewish cemetery was established in Wiesbaden; it was later expanded and renovated several times, and was also used by Jews from other communities. At the end of the century, a Jewish coffee house opened in Wiesbaden.

The Jews of Wiesbaden were allowed to trade in luxury goods for vacationers in the city, and during the 19th century most of the Jews became established in trade; some were property owners, and Jews also figured prominently among the practitioners of the liberal professions in the city, some of them practicing law and medicine. A number of Jewish residents of Wiesbaden established Jewish bath houses, but by the mid-19th century mixed (Jewish and non-Jewish) bath houses were permitted, and the Jewish bath houses were closed.

At the beginning of the 19th century there were some 150 Jews in Wiesbaden, about 2% of the city’s population. Until this time Jewish children studied with private teachers, who were hired by three or four families together, or in the traditional heder (religious primary school). Following legislation making public education mandatory, Jewish children began attending government-run public schools in the city. However, Jewish teachers were allowed to continue residing in the city, on the condition that they limited themselves to teaching religious subjects.

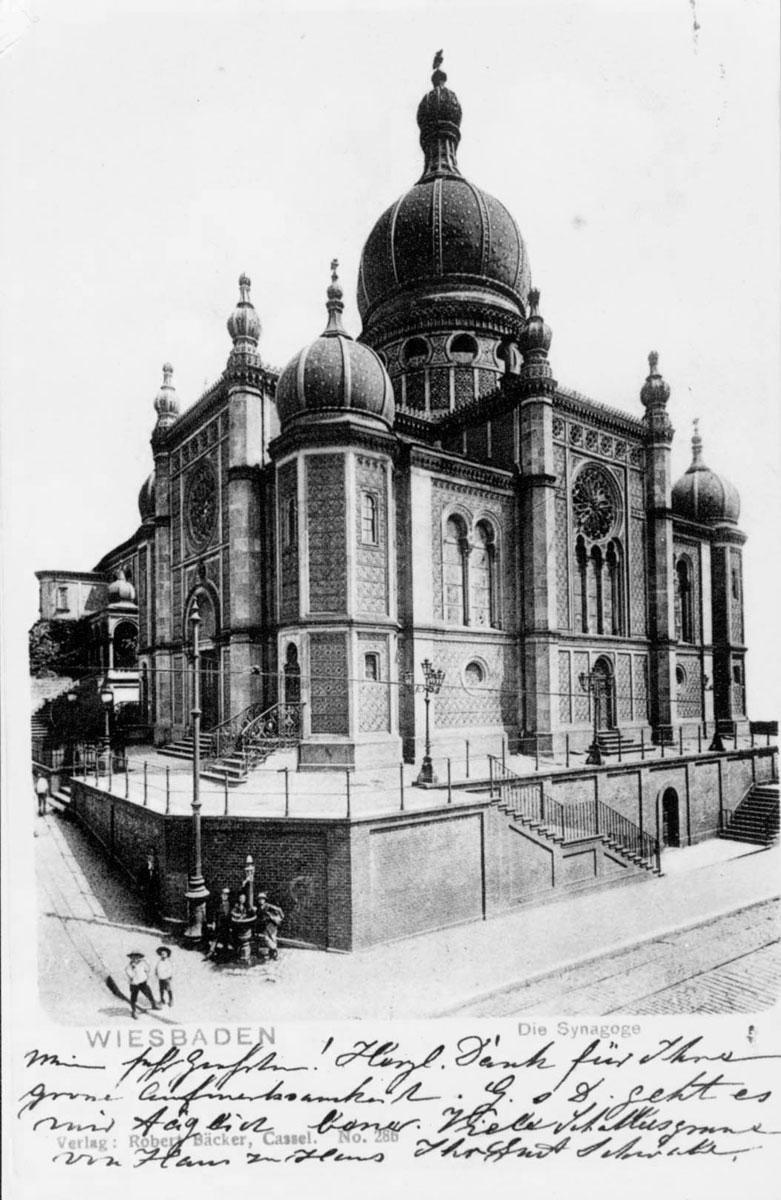

The Jews made use of an old synagogue as well as an improvised synagogue that was established above a stable; however, the municipality declared the building unsafe, and it was subsequently closed. In 1826, a new synagogue seating 200 was established, with funds from the community and Jewish philanthropists. In 1869, another more spacious and elegant synagogue was built in the Moorish style. This synagogue had seats for several hundred men, a separate women’s section that also held several hundred seats, and an organ. The synagogue’s choir performed in the synagogue at a festive concert conducted in the presence of the King of Prussia. The same year a community center was built, and later on kosher guesthouses catering to religious visitors were also opened.

During the 19th century the Jewish community of Wiesbaden was well-established financially. Some of its members were pensioners who came to spend their later years in the city. There was only one Jewish family that required full support from the community’s charity fund. The Jewish-owned bath houses provided free bathing for poor and sick Jews. The city also had foundations to aid students and charitable foundations that provided aid for the sick, as well as a Jewish choir accompanied by an organ. Many young Jewish women sang in the choir, which performed at holiday festivities, charity nights, theater performances and concerts. The chief cantor of the general community, Abraham Nussbaum, was instrumental in establishing the liturgical practices for the public prayers, which he described in his book, “The Liturgy of the Wiesbaden Synagogue”.

Between 1832 and 1838, Abraham Geiger was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Wiesbaden. Geiger was one of the leaders of the German reform movement, and one of the most prominent researchers of the newly-founded discipline of Jewish Studies (Wissenschaft des Judentums). During his tenure as the rabbi of Wiesbaden, Rabbi Geiger laid the foundations for the Reform Judaism movement. He participated in religious instruction for children, adapted curricula and confirmation ceremonies for young men and women from the Protestant model, published an academic journal on theological Judaism, and introduced innovations into the communal prayers. Among Rabbi Geiger’s innovations was the introduction of a weekly sermon in German, the omission of some of the liturgical poems and the establishment of confirmation ceremonies. In 1837 Rabbi Geiger convened the first meeting of the Reform rabbis in Germany, which took place in Wiesbaden. His successors introduced additional educational and religious reforms, among them an obligatory weekly lesson for Jewish youths on Saturdays; non-attendance at the lesson incurred a fine. During his time as the community’s rabbi, Rabbi Shmuel Ziskind introduced yet further reforms, which included the use of an organ to accompany the choir during services.

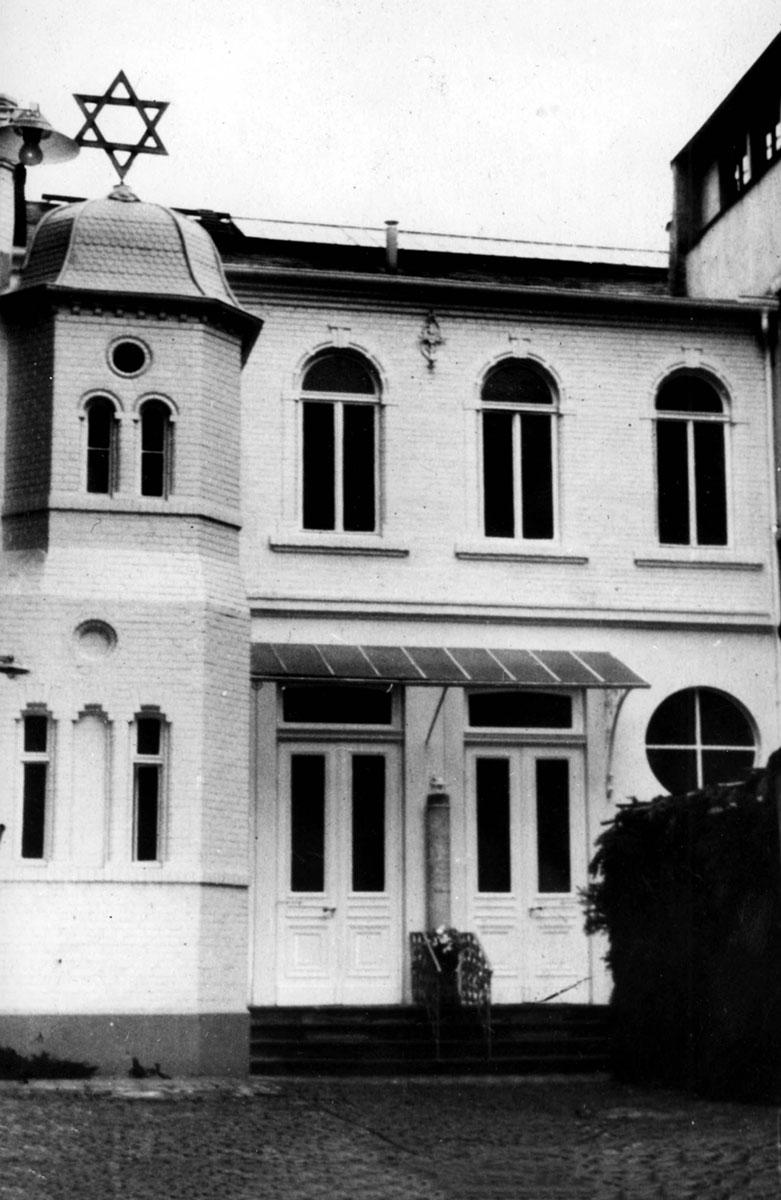

In the second half of the 19th century, several Orthodox families left the Jewish community in light of the reforms in the liturgy at the new synagogue. They established the Old Israelite Community (Altisraelitische Kultursgemeinde), which had a separate cemetery and synagogue.

At the end of the 19th century there were some 1,700 Jews in Wiesbaden, amounting to about 2% of the city’s population.